KIRK DOUGLAS & CARRIE SNODGRESS, CLANDESTINE OR OTHERWISE

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | February 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

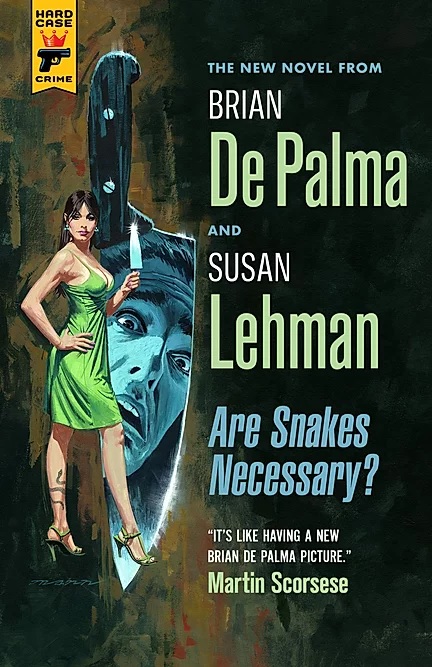

Are Snakes Necessary? hits the streets on March 17th, but some early reactions to the novel, co-written by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman, are beginning to show up online. "Read Are Snakes Necessary? in one night and it really is like a Brian De Palma's greatest hits of obsessions, fixations and fetishes," author Jedidiah Ayres wrote in a Twitter post yesterday. "Loved it," he continued, adding, "All I want to do now is watch Femme Fatale again."

Are Snakes Necessary? hits the streets on March 17th, but some early reactions to the novel, co-written by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman, are beginning to show up online. "Read Are Snakes Necessary? in one night and it really is like a Brian De Palma's greatest hits of obsessions, fixations and fetishes," author Jedidiah Ayres wrote in a Twitter post yesterday. "Loved it," he continued, adding, "All I want to do now is watch Femme Fatale again."Writer Nick Kolakowski chimed in with a link to his review at Mystery Tribune, tweeting, "It really does win every single square of De Palma bingo, but I had some... issues with it."

To which Ayres replied, "It's... slight? But so pleasingly symmetrical."

Adlerberg then added, "It’s a little slight, I guess. And the writing style is a bit bare bones and screenplay like, but does that matter really? I like how tongue and cheek it is."

Here's an excerpt from Kolakowski's review at Mystery Tribune:

On the cover of “Are Snakes Necessary?”, the thriller authored by legendary director Brian De Palma (co-written with Susan Lehman), there’s a blurb that many a noir writer would commit literal murder for: Martin Scorsese announcing that this book is “like having a new Brian De Palma picture.”As a blurb, it’s dead-on, and therein lies the rub: If you’re a fan of De Palma’s cinematic work, this book may very well scratch that itch for another thriller from the maestro, albeit in a totally different format. If you’re one of those folks who dislikes the director’s hothouse Hitchcock homages, then you’re no doubt going to roll your eyes as the book trots out pretty much every single De Palma trope of the past 45 years.

Psychosexual shenanigans? Check. Political malfeasance? Check. Unscrupulous people doing their level best to one-up each other? Check. Knife deaths? Check.

Hitchcock-style tumble from a really tall, internationally famous landmark? Oh yeah, big check. Not to spoil too much, but a climactic incident “happens in that funny slow-motion way that events unfold in the heat of certain moments,” to quote the narration directly.

It’s like De Palma is attempting to do in print what he’s done so notably in some of his most famous films (the train-station shootout in “The Untouchables,” the cross-action finale of “Raising Cain”); the paragraphs become individual shots, the action so clear you could storyboard it.

Indeed, if there’s one minor quibble to make with the book, it’s the pacing. Within chapters, the narrative will suddenly jump to that night, or even a few weeks later; it would work in a movie, where a single cut is all you need to seamlessly suggest that time has elapsed, but it’s jarring in prose.

For those who grew up watching, re-watching, and generally enjoying De Palma’s films, perhaps the biggest surprise here is the tone. His movies’ characters might be psychologically twisted wrecks, but De Palma always approached pacing, framing, and the other elements of filmmaking with a surgeon’s eye, expertly dialing in his effects. Yet the book’s tone is casual—“folksy” is probably the wrong word to use, but that term hints at its relaxed nature.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: You’ve played your share of morally murky or evil characters, on American Horror Story and in 12 Years a Slave, for instance. What makes Diane unique in your filmography?FLASHBACK - 'AMERICAN HORROR STORY: ASYLUM'

SARAH PAULSON: I don’t know that I ever look for uniqueness in a character in terms of my wanting to do something or not. I was really interested in working with Aneesh, because I really loved Searching, and thought it was an incredibly inventive way to tell a story we’ve seen before. So I was really drawn to the project because of that, mostly. But I always also like exploring things that I myself have not really experienced in my life. I’m not a mother, and I think from an acting standpoint it’s always challenging to try to find some way to root yourself in a reality you know nothing about.[Diane and Chloe] live a very isolated life, and they really only have each other. But Chloe’s at that point in her life now where she’s starting to want to explore beyond the confines of her very isolated life, which is very normal. But I think Diane finds that very scary in the way that most parents do, the minute their children are interested in flying the coop. Diane just may have particular feelings that go a little bit more to the extreme, is all.

There’s a rich history of these sort of difficult mother characters on screen. Was there anything or anyone in particular that you drew on for inspiration? I drew mostly on my experience watching Piper Laurie in Carrie. Although it’s a different dynamic, it’s still a dynamic that is a very tense one. There’s an element of control, there’s obviously an extreme codependent situation at work there, where you have a young person who is slowly coming into their own and what that causes the parent to feel. I did watch that movie more than once in preparation for this one.

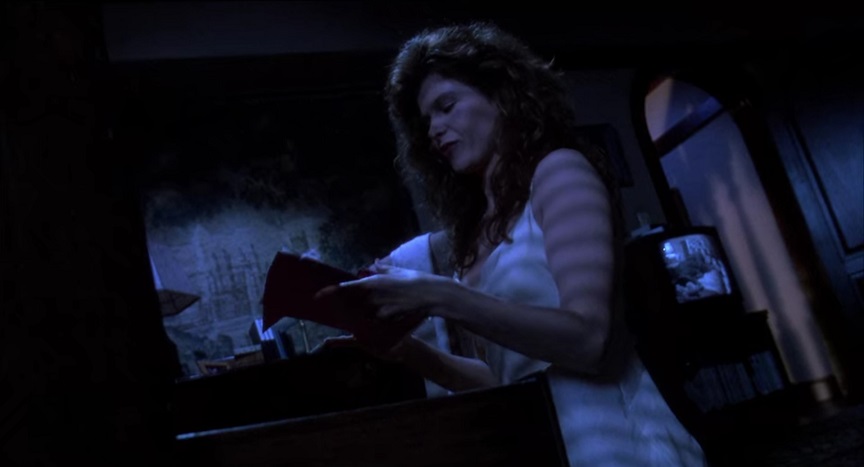

[Possible Spoilers] So I'm watching the season premiere earlier tonight of American Horror Story, the F/X series created by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk, and about 10-15 minutes in, I hear this very familiar Pino Donaggio music. At first I wondered if it was just a little musical homage to Donaggio's "Bucket Of Blood" cue from Brian De Palma's Carrie, but as it went on, it became clear to me that it was that precise recording-- it was indeed "Bucket Of Blood," edited to fit in with what was happening on screen.

And the scene in question was the introduction of the character pictured here, Lana Winters, a journalist played by Sarah Paulson. "Bucket Of Blood" (as the track was titled on the original Carrie soundtrack release) plays as Lana approaches the asylum (in 1964) that provides the main setting of season two-- and the Donaggio track is repeated twice more in the episode, creating a little motif for Lana. Lana is working on a story about the asylum under the false pretense of doing a fluff piece on the bakery run by Sister Jude (Jessica Lange). The "Bucket Of Blood" cue is heard a second time, just moments later in the episode, during the scene pictured here: Lana is watching as the latest "patient" (Kit Walker, played by Evan Peters) is delivered to the asylum, and the music builds suspense as he is led up the stairs, and the Donaggio crescendo peaks as Kit is stripped and thrown into a shower stall.

In between these two "Bucket Of Blood" cues is another Donaggio cue from Carrie: "For The Last Time We'll Pray" plays as Lana makes her way inside the asylum for the first time. Sister Mary (Lily Rabe) leads Lana up the stairs to meet Sister Jude, and they walk in on her just as she is beginning to shave the head of a patient, Shelly (Chloe Sevigny).

Now before I get to the third use of "Bucket Of Blood," which comes later on in the episode (confirming the running motif), it is worth noting that Sevigny portrayed Grace Collier, the journalist, in Douglas Buck's 2006 remake of De Palma's Sisters. This, of course, is the journalist character who was played by Jennifer Salt in De Palma's Sisters. Salt is an executive producer on American Horror Story, and she wrote a couple of episodes from the first season. This current episode, and, it would appear, the season to come, has clear echoes of De Palma's Sisters, in which Grace, investigating a murder, infiltrates a mental health clinic. However, Grace is discovered and captured by Dr. Emil Breton (William Finley), who tricks the others at the clinic into thinking Grace is a stray patient. "You want to know our secrets," Emil says to Grace as he puts her under a hallucinatory sedation. "We will share them with you. Watch." On American Horror Story, Lana is eventually discovered and captured in a similar manner. "She wanted an inside look into our facility," Sister Jude later tells Lana's roomate, "and I will see that she gets it."

But before that happens, "Bucket Of Blood" is heard a third time as Sister Mary appears to be feeding someone or something in the woods, and the music this time crescendos as Lana herself startles Sister Mary-- bringing Lana's appropriated Donaggio motif full circle.

Appropriating themes from horror movies is nothing new for American Horror Story. Last season, Bernard Herrmann's whistling theme from Twisted Nerve was used as a recurring theme for Evan Peters' character. (That same theme had previously been reappropriated by Quentin Tarantino for a memorable De Palma-Dressed-To-Kill-esque split screen sequence in Kill Bill Vol. 1.) For all I know, there were other such music cues that I did not recognize. But I wouldn't be surprised to hear "Bucket Of Blood" again throughout the season, if Lana's story continues.

AVC: Who are your favorite directors of all time, and who are some younger directors you’re excited to see more from?BJH: Among contemporary directors, I really admire the horror films of Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. In the generation above that, I have affection for De Palma. But I think that if you climb up that pyramid [Draws a triangle with his hands.] at the very top is Hitchcock.

AVC: I agree.

BJH: I’ve admired him since I was little, and I think I’m under his umbrella as well.

Diamond, however, left out the mentions of Brian De Palma and Sam Peckinpah, so here's an excerpt from Citypages' Bryan Miller:

Quadruple Oscar-winning director Bong Joon-ho arrived at the Walker for the 30th anniversary of their Dialogues series just days after he made history at the Academy Awards with his masterpiece, Parasite. He told interviewer Scott Foundas he’d taken Monday to rest from the night’s festivities, then boarded a plane Tuesday for Wednesday’s talk that concluded a partial retrospective of his work. He was still reeling.“It happened four days ago. Three days ago?” Bong asked, and not rhetorically. “It feels like three years ago.”

It was, he said, a great thing he needs time to process. “It’s still hard to understand.”

He demurred when former Variety critic and Amazon development executive Foundas inquired about his surreal Sunday night, being crowned Best Director and receiving a Best Picture award, but the auteur opened up when the audience couldn’t stop asking about it during the later Q&A.

Bong admitted he thought Parasite’s best chance was for Best International Feature—pausing to apologize for his presumption to fellow nominee Pedro Almodovar, whose Pain and Glory he called “a beautiful movie”—and after he won he felt tremendously calm, expecting nothing more from the rest of the ceremony.

Then the presenters kept saying his name again, and again, and again.

When he took to the stage to accept the award for Best Director, he had no planned speech. He happened to lock eyes with Martin Scorcese. On the spot he felt moved to pay tribute to the Irishman director, which led to the moving standing-O for Scorcese. After that, Bong said he wished he could share the award with his fellow nominees, dividing it into five parts “with a Texas Chainsaw.” “I still don’t know why I talked about Texas Chainsaw. Very strange,” he admitted on Wednesday, chuckling.

In his homeland of South Korea, he’s known as "Director Bong," a fittingly authoritative title for an artist whose films are so precise and supremely controlled. Yet it belies the jolly nature of the man with the boyish mop of hair, who carries himself with graceful nerdiness and isn’t shy about sharing his big, generous laugh. He arrived onstage wearing all black—from socks to suit to undershirt—but he punctured any dour auteur vibes when he started spinning Foundas’s rotating chair as they turned to watch a clip from one of his films. His genuine humility was on display when he confessed he thought his debut film, Barking Dogs Never Bite, was “disappointing” and “amateurish.”

“I’m so happy Barking Dogs wasn’t included [in the retrospective],” he said, laughing as he waved the program in the air. “Never watch that!”

Seven films into his career, Director Bong has earned a global reputation as an undisputed master. It’s fitting that he’s the first director to make a non-English-speaking Best Picture winner, as he’s truly an international director, shifting as fluidly between Korean and English (with some help from a translator on Okja and Snowpiercer) as he does between film genres.

American genre movies are “the blood flowing through my veins,” he explained; you don’t ever think about the blood in your veins, you just know it’s there. He first glimpsed these American movies in edited form on then strictly censored Korean television, and got an unfiltered look at the films of Hitchcock and DePalma and Peckinpah, which were unedited but also untranslated, on the U.S. military’s Armed Forces Korean Network. Years later he’d see the same movies translated in his college film club and contextualize the images burned into his brain. His aim became to merge “the joys of genre with the realities of Korea.”

Foundas screened clips from several movies while Director Bong shared an array of fascinating tidbits of their origins—like how he wrote Mother for actress Hye-ja Kim and would have scrapped it if she hadn’t agreed to star, or how he pondered the first half of his acclaimed Parasite for four years, but only conceived of the twisty second half of the film in the final few months of writing the screenplay, which dug deeper into the class-conscious themes that pervade his work.

Foundas joked that when they spoke a few years prior, Director Bong explained he had to go back to South Korea to make a smaller movie out of contractual obligation to the producers of Mother—the film that would eventually become Parasite.

“You couldn’t have made it sound less significant,” Foundas marveled.

Director Bong said he felt “happy” and “safe” in Parasite’s intimate world, working with his frequent collaborator, actor Song Kang-ho.

Funny, because nothing about Director Bong’s work feels safe. He’s become the face of the incredibly rich Korean film culture that includes massive talents like Park Chan-wook, Kim Jee-woon, and Lee Chang-dong. This group of filmmakers, Director Bong says, have more of a loosely shared aesthetic as opposed to a conscious collective movement like Dogme 95 or the French New Wave.

“We’re the first generation of Korean cinephiles.”

Before Brian De Palma made his mark as the new master of suspense with “Carrie” and “Dressed to Kill," he made a couple of counterculture-skewing satires that hold up very well today as mischievous documents of a turbulent time. The best of these is “Hi, Mom!," a sequel of sorts to “Greetings,” that stars Robert De Niro as a voyeuristic adult filmmaker. The film is basically a collection of vignettes, the highlight being a guerilla theater performance of “Be Black, Baby," in which white theatergoers are coated in blackface and terrorized by the African-American actors. It’s a searing sequence that is as masterfully orchestrated as anything in De Palma’s impressive oeuvre.

After delving into detail regarding the happenings in Blow Out, Rabin continues:

The police and the powers that be are eager to write off the death as a tragic accident. But Jack is convinced that an assassin shot the tire of the car the night of the incident to cause the deadly accident and pores meticulously through tapes of the evening to piece together what happened and who is responsible.Jack’s obsessive exploration of the night of the accident puts him on a collision course with Burke (John Lithgow), the lunatic responsible for the blow out of the tire and the politician’s death. I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to call Lithgow’s glowering sociopath one of the greatest villains in the history of American film.

I would happily watch a Blow Out prequel focussed exclusively on Burke’s character, that illustrated exactly he came to be such a fascinatingly fucked-up, utterly amoral human being. Burke was ostensibly acting under orders when he shot the car but it’s apparent that the cold-blooded killer is always willing to improvise it means killing more people.

Burke seems like the kind of guy who got into the assassination game primarily because it affords so many literally killer opportunities to wrack up bonus murders in the form of witnesses, loose ends and pretty much anyone who needs to be killed, which in Burke’s mind is pretty much everyone in the world besides himself.

It’s crazy and impressive that Lithgow can simultaneously be the very image of genial, avuncular warmth and the scariest, most evil motherfucker alive, which is a good description of the mass murderer he plays here. Like Christian Bale in American Psycho, there’s an unfathomably vast emptiness at the core of his being where his soul and morals should be.

Like Patrick Bateman, Burke suggests a malevolent space alien who can only pretend to be a human being because he possesses no genuine humanity. Burke is an actor playing the role of someone with feelings and emotions and objectives beyond killing as many people as possible and getting away with it.

Though he occasionally works with, and for, other people, Burke is, at his core, a solitary man, a lonely figure cut off from the rest of humanity by his peculiar and unfortunate line of work and also his compulsion to kill in both socially sanctioned ways and just for fun and sport.

In the time-honored tradition of psychological thrillers, the solitary killer obsessed with tying up the loose ends on his biggest murder to date and the ex-cop obsessed with solving a crime the gaslighting powers that be insist doesn’t exist are weirdly simpatico figures, lonely men on lonely missions only they seem to understand.

In a lesser movie, that convention might qualify as hackneyed and cliched but DePalma, who wrote the screenplay as well as directing, breathes passionate life into this hokey old trope. DePalma knows how to get the most out of Travolta as an actor as well as a movie star.

Travolta is charismatic and magnetic enough to be absolutely riveting doing nothing more than listening for sounds but DePalma’s script gives him a real, nuanced character to play with a fascinatingly lived-in backstory and a code of ethics that sets him apart from every other character in the film.

Travolta’s obsessed sound man is moved to do what’s right even when he has nothing to gain by doing so and everything to lose. Everyone else is motivated by money or lust or power or convenience. In a world of scumbags, Jack is a decent man.

Blow Out is a product of the 1980s but it feels like a 1970s movie in many ways, including its very post-Watergate conviction that American audiences will inherently assume that politics, particularly at the very highest levels, are inherently corrupt and duplicitous, and consequently prone to believe conspiracy theories involving malevolent forces working furtively behind the scenes.

DePalma makes brilliant use of the star-spangled, flag-waving history hometown of his hometown of Philadelphia, particularly in regards to the Liberty Bell and a climactic patriotic parade to pointedly and ironically juxtapose our country’s idealized, romanticized past and ideals and its dark, dystopian contemporary reality, which is that bad people get away with murder and the truth is sometimes so deeply hidden that no one even thinks about looking for it.

Blow Out is a meticulous movie about a meticulous man, a masterpiece of total virtuosity from an auteur operating at the very apex of his ability. I know that there are lots of people who dislike DePalma for a wide variety of reasons, many of them quite valid, but watching Blow Out, I fell in love with DePalma as a filmmaker and a storyteller all over again.

THIS is filmmaking. THIS is mastery. THIS is the work of someone who knows exactly what he wants to do as a filmmaker and does it. DePalma is in total control of his craft. Everything pays off in a dark and inspired and unforgettable way, perhaps most famously the search for a convincing scream that opens the film.

Spoilers if you haven’t seen Blow Out yet, but Jack wires Sally with a microphone, who is murdered by Burke just before Jack can save her. Jack manages to kill Burke but he’s understandably despondent and, like many grief-ridden souls, throws himself into his work.

In a real Monkey’s Paw type situation, Jack achieves his goal of recording the most realistic scream in the history of slasher movies in the form of Sally’s dying noises. The scream sounds real because it is real. For the sake of verisimilitude, Jack transformed a genuine howl of death from someone in the process of being brutally murdered into the ultimate in hardcore sound effects.

It’s a shame that DePalma has to kill a character as sympathetic and messily human as Sally but this is DePalma so of course a movie that begins bleak, and only gets bleaker would end on a darkly hilarious, hilariously dark note.

The gut-punch of an ending helps explain why audiences at the time rejected Blow Out. Even by DePalma standards it’s grim and obsessed with the mechanics of film and the filmmaking process but it’s a thriller that’s also just about perfect. There is not a thing I would change about it, from the scumminess of a low-rent photographer played by Dennis Franz, winner of the Academy Award for Dirtiest Undershirt, to the director’s trademark use of split screens and deep composition.

Seitz responded, "There was an interview where he said he thought that was the movie he would be remembered for, and it was difficult to tell if he was genuinely enthused by the prospect, or if he had that old director thing where the film that made the most money is by definition 'the best.'"

Based on my conversation with De Palma in 2002, it would seem he probably saw that prospect as a simple matter of fact. Yet, even though De Palma had smuggled a personal film into his biggest commercial blockbuster (in the Scorsese sense of "the director as smuggler"), De Palma, to me, would seem to be more enthused at the prospect of being remembered for something like Blow Out, or even, perhaps, Carlito's Way. The latter two films are the ones he had personally chosen to open and close his 2002 retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. In any case, Mike Ryan's tweet about Mission: Impossible led to a whole lotta love for De Palma's film in response.

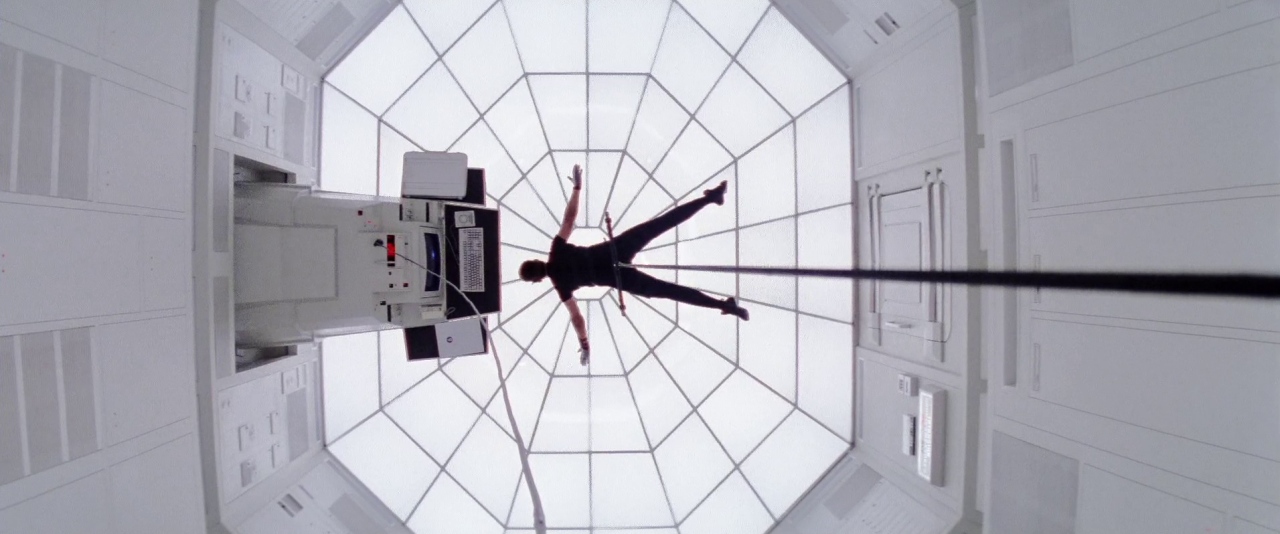

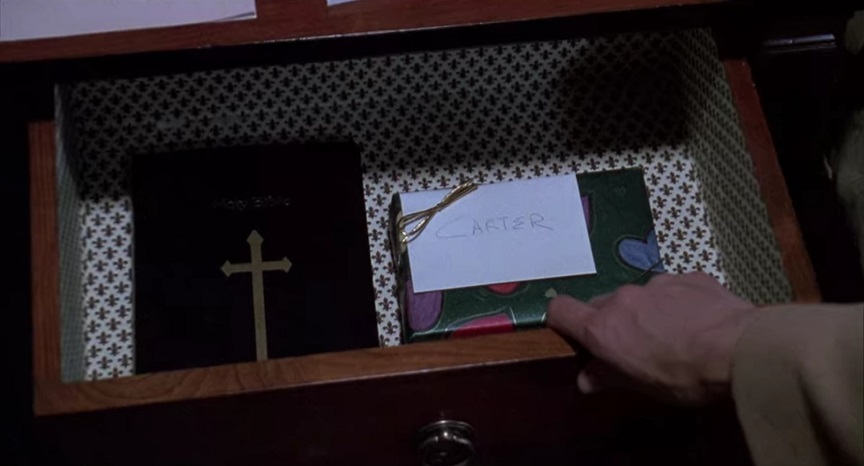

Meanwhile, this past Wednesday, Film School Rejects' Margaret Pereira posted an article with the image above, and the headline, "The Shot That Made Mission: Impossible." A subheadline reads, "We take a deep dive into the first of many memorable Mission: Impossible shots." Pereira's article then begins:

The iconography of movies is always a little unstable. The imagery and symbolism that are legible to an audience depend so much on the cultural, historic, and generic context. There are even entire academic subfields dedicated to studying it. The visuals we associate with certain themes or characters can be as simple as the Batman logo and as nuanced as Han Solo’s smirk. But there are also images so powerful that they immediately seep into the filmic bloodstream and soak into every nook and cranny of culture. Mission: Impossible contains one of these images.Tom Cruise, suspended by a single cable, hanging over a computer console. His black secret-agent garb contrasting with the pristine white background. Utter silence. It’s almost absurd that it’s so simple. Directed by Brian De Palma, the 1996 adaptation of the TV series of the same name finds Ethan Hunt (Cruise) embroiled in the first of many scraps with the IMF. Ethan’s been accused of double-crossing, in a botched mission that found the rest of his team dead (or so he thinks). To clear his name, he must steal a list that reveals the secret identities of all operatives in the IMF and team up with a smattering of ex-agents to do so.

In truth, it doesn’t particularly matter what he needs to steal and who he needs to steal it for. This first entry in the Mission: Impossible film franchise spends a lot of time explaining the exact circumstances of the conspiracy. It’s something later movies will mostly abandon — we just get that Cruise has to hang off the side of a plane and we’re happy with that. In fact, the labyrinthine plot of Mission: Impossible contributes to the power of this single shot. The stunning immediate impact of the shot has all viewers forgetting briefly the scene’s narrative purpose and instead investing in the film emotionally. You’re too anxious to be concerned with the specific reason why we’re in this room.

Part of what builds this intense anxiety is the circumstances of the break-in. Alarms will be activated if any sound is too pronounced, a gauge notes the room’s average temperature, and the floor has a sensitive pressure sensor. Because of this, Ethan has to be suspended directly in the middle of the room. The way Cruise’s body breaks up the geometric design of the space adds a lot of visual interest and thematic weight. This bunker is designed solely to keep information in, the secrets of which Ethan must expose to get his life back. He descends into this hyper-codified, precisely organized space as a major disruption. It mirrors the way he disrupts the plans of his adversaries and even his status as a generally rogue agent in future movies.

What’s masterful about De Palma’s approach here is the way he implicates the audience in this shot. While many filmmakers emerging from the more-is-more school of thought might add the classic musical twang here, De Palma opts for silence. Ethan must be dead quiet so as not to trigger the alarms, and we realize that we must be as well. By extending the rules of the story world using sound (or rather a lack of sound), De Palma connects us more deeply to Ethan and his mission.

De Palma also ensures the camera’s slow descent into the space with Ethan leaves the audience hanging on for dear life. The camera never feels like it’s resting on the ground; it’s hovering. Our perspective is just as precarious as his. Ethan is our lifeline; he’s the only one who’s hooked into the cable. We’re forced to trust him. All of these techniques cause the throat-catching, breath-holding effect we’ve come to expect from the Mission: Impossible movies.

There exists a grand meta-narrative of the Mission: Impossible franchise, wherein Tom Cruise is the Ethan Hunt of Hollywood filmmaking. Cruise refuses to let his audience down; he comes back again and again even when we say we’ve had enough. No scandal can keep him down for too long; no box-office disappointment can force his retirement. He’ll hang off the side of a building or jump out of an airplane if he has to, whatever it takes to get his mission done. This film, and particularly this shot, help begin that dynamic.

Mission: Impossible was also the first film Cruise ever produced, and he’s clearly aware of the importance of his own iconographic effect in this movie. Cruise’s producing career includes the rest of the Mission: Impossible films, along with a couple of Jack [Reacher] films, and most recently, Top Gun: Maverick. These projects are a sign of self-awareness in Cruise; he knows what his audience wants to see and is willing to back it financially and creatively. Mission: Impossible cemented his status as a movie star as well as a major creative force in 21st century Hollywood.

Not every movie star would understand that his visual impact lies in being a spatial disruption. The image of Cruise’s body suspended in mid-air isn’t particularly macho or sexy. It simply signifies to audiences the most important part of his persona: he’ll never drop us. This shot sticks in our collective craw certainly because of the gorgeous construction and the utter silence. But even more than that, it establishes Ethan Hunt as the character willing to risk it all, and Cruise as the only actor who could ever convincingly play that. Mission: Impossible created the visual symbolism of Tom Cruise, and his impact will be forever meaningful to audiences because of it.

The Fury was my first starring role. This was a real big deal for me. And I had a certain way of working, getting myself there emotionally to play the character. I wasn’t very experienced in front of the camera at all. So, while Brian De Palma was setting up shots, I was sitting in my little director’s chair, in my own world, concentrating on where I’m at in the scene — I was taking it really seriously and getting myself into an emotional state. And as tears were rolling down my face, Kirk came over to me."Are you all right?" he asked. I told him I was just preparing. He said, "Amy, first of all, you’re what, 23 or 24 years old? You’re never going to make it to 30 if you put that much into everything while they’re lighting the set. My advice to you is, A, save it and use it when the camera is rolling. And, B, did you not hear what lens he was using on this shot? With that lens, you’re going to be the size of a pea on the screen. It really doesn’t matter how emotional you are."

It was a really good lesson. And he was right. I probably would not have made it to 30 if I had not had that sage advice from Kirk Douglas.

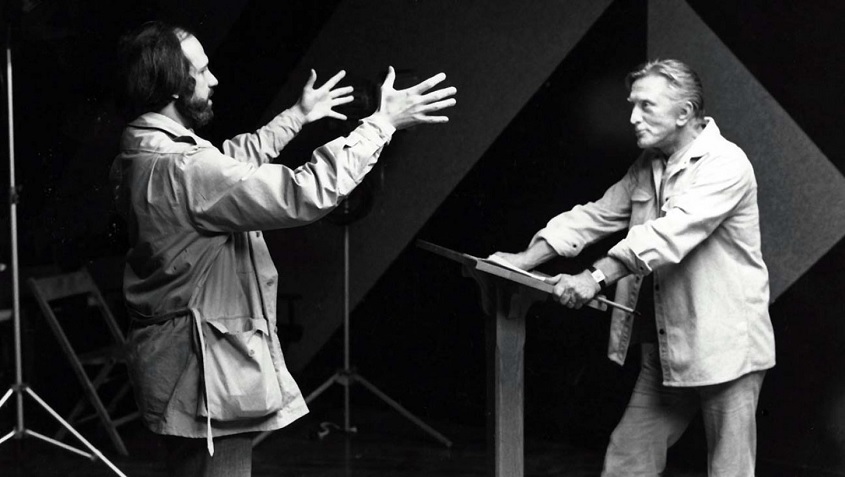

When I was teaching a filmmaking course at Sarah Lawrence College in the late 1970s, Kirk joined me in producing a super-low-budget feature titled Home Movies. My concept for the course was to show the students how to make a low-budget feature by making a low-budget feature. Once the class had written the script, we sought out financing and started casting. Since Kirk and I had enjoyed working together on The Fury, I asked him to join our project.He agreed immediately and even invested in it with me (along with George Lucas and Steven Spielberg). My students were shocked and surprised: "My God," they exclaimed, "we have Kirk Douglas in our student movie!" They created and wrote a character — a film school teacher called the Maestro — for him to play. I have fond memories of Kirk sitting on a tree branch with his co-star Keith Gordon in the middle of the night instructing him on the virtues of Star Therapy ("You must be the star of your own life," his character lectured, "not an extra!").

A star: No one embodied it better.