KIRK DOUGLAS HAS DIED, AT 103

MICHAEL DOUGLAS SHARED THE NEWS TODAY IN AN INSTAGRAM POST Kirk Douglas

Kirk Douglas has died today, at the age of 103. His son,

Michael Douglas, shared the news today in a heartfelt

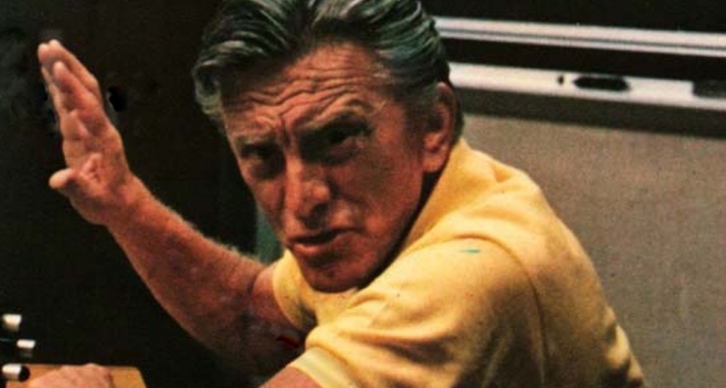

Instagram post. Kirk Douglas, a legend of the screen from the golden age of Hollywood, starred in

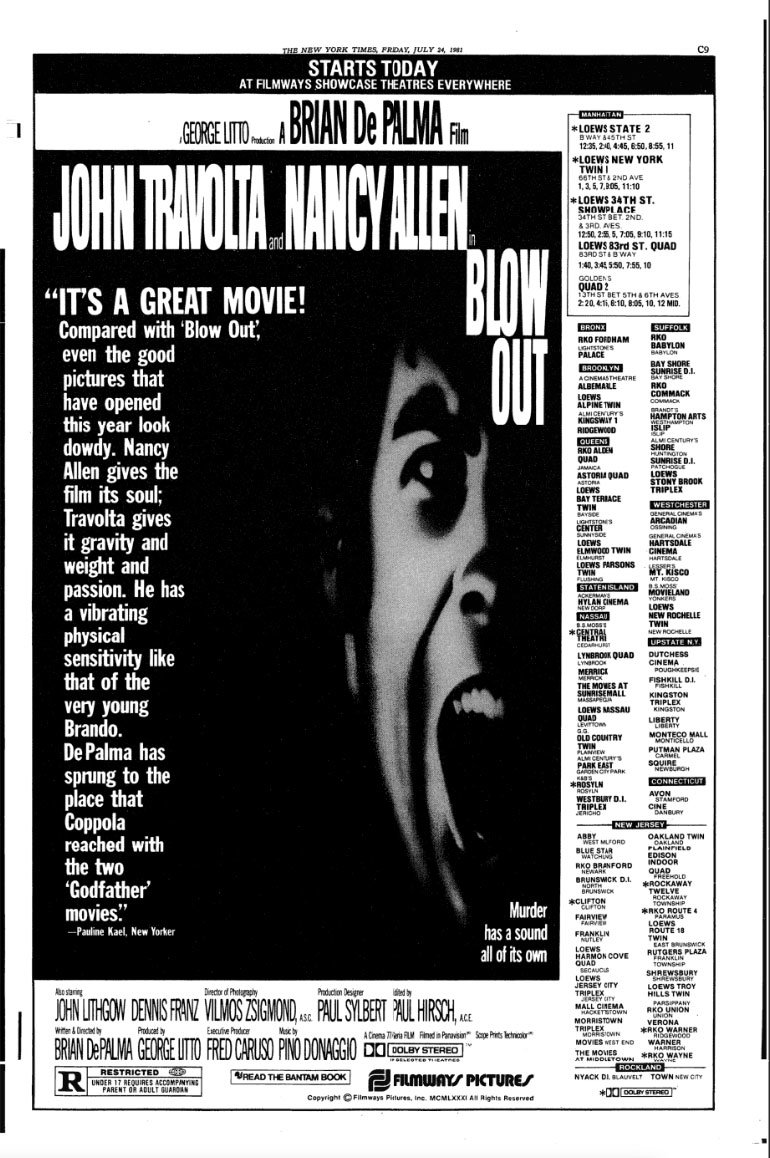

Brian De Palma's

The Fury. Asked upon the film's release in 1978 why he cast Douglas as the lead, De Palma told

Paul Mandell of Filmmakers Newsletter, "I like Kirk Douglas and I've also liked a lot of his films, although in the last couple of years he's been in some not-so-hot ones. I wanted the kind of driven, obsessive character he plays so well. At one point I said to

Frank Yablans, 'We need a Kirk Douglas type.' And he said, 'Why don't we get Kirk Douglas?' Kirk had worked with Frank at Paramount before, so the next thing I knew I was talking to him on the phone. Kirk was great! He has a lot of experience and he brings all those years of movie-making to your film."

In an obituary at The Hollywood Reporter, Mike Barnes and Duane Byrge describe Douglas as "the son of a ragman who channeled a deep, personal anger through a chiseled jaw and steely blue eyes to forge one of the most indelible and indefatigable careers in Hollywood history."

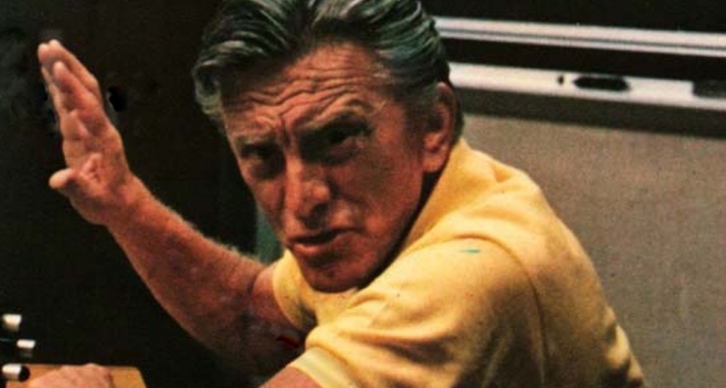

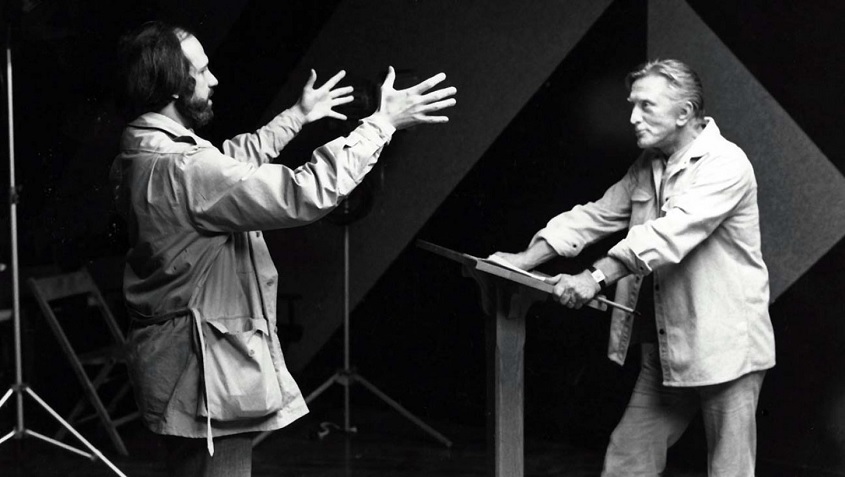

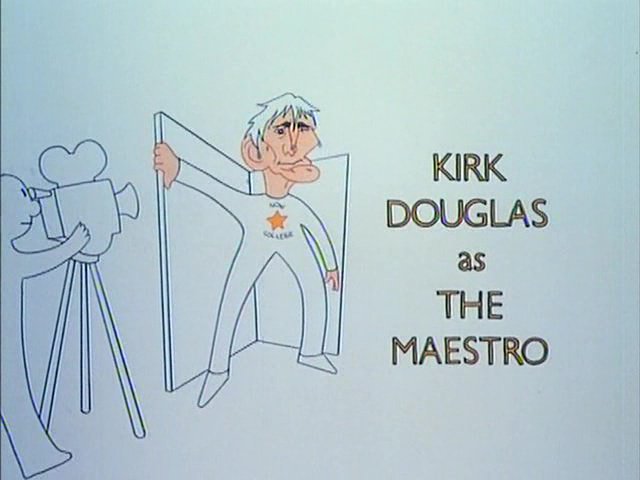

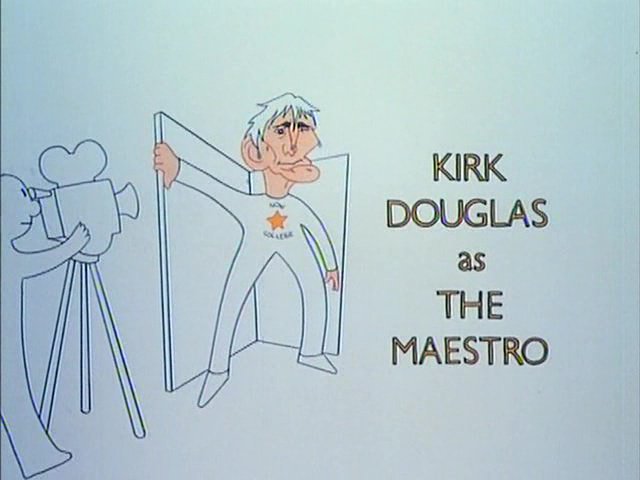

After working on The Fury in 1977, Douglas had heard De Palma was making an independent film with film students at Sarah Lawrence College. According to De Palma (in an interview with Gerald Peary for Take One magazine), Douglas had called him and said, "Maybe I can help you out." After reading the script, Douglas wanted to play a part. He became an investor, putting in some of his own money, and also became the star of the film, which would be titled Home Movies (from a script De Palma had written years prior). With a big star like Douglas on board, playing a character called "The Maestro," no less, De Palma feared some of the students might feel a bit intimidated, which might then affect the quality of the film they were making. De Palma made the decision to take on the official role as director of the film, even though he let his students direct the scenes wherever possible. In addition, he hired professionals to head each department.

"All of Kirk's stuff is shot cinema verite," De Palma told Peary, "and his own Star Therapy is to have cameras running on him all the time. He's constantly directing the camera crew that's shooting him, telling them to come around for closeups, over here for a medium shot. When the lab saw the stuff, they thought Kirk was directinig the movie."

Here's an excerpt from the Hollywood Reporter obit:

Douglas walked away from a helicopter crash in 1991 and suffered a severe stroke in 1996 but, ever the battler, he refused to give in. With a passionate will to survive, he was the last man standing of all the great stars of another time. Nominated three times for best actor by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences — for Champion (1949), The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) and Lust for Life (1956) — Douglas was the recipient of an honorary Oscar in 1996. Arguably the top male star of the post-World War II era, he acted in more than 80 movies before retiring from films in 2004.

"Kirk retained his movie star charisma right to the end of his wonderful life, and I'm honored to have been a small part of his last 45 years," Steven Spielberg said in a statement. "I will miss his handwritten notes, letters and fatherly advice, and his wisdom and courage — even beyond such a breathtaking body of work — are enough to inspire me for the rest of mine."

The father of two-time Oscar-winning actor-director-producer Michael Douglas, the Amsterdam, New York native first achieved stardom as a ruthless and cynical boxer in Champion. In The Bad and the Beautiful, he played a hated, ambitious movie producer for director Vincente Minnelli, then was particularly memorable, again for Minnelli, as the tormented genius Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life, for which he won the New York Film Critics Award for best actor.

Perhaps most importantly, Douglas rebelled against the McCarthy Era establishment by producing and starring as a slave in Spartacus (1960), written by Dalton Trumbo, making the actor a hero to those blacklisted in Hollywood. The film became Universal’s biggest moneymaker, an achievement that stood for a decade.

Douglas’ many honors include the highest award that can be given to a U.S. civilian, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The broad-chested Douglas often bucked the establishment with his opinions, and he had the courage to back them up. “I’ve always been a maverick," he once said. "When I was new in pictures, I defied my agents to make Champion rather than appear in an important MGM movie they had planned for me [The Great Sinner, which wound up starring Gregory Peck]. Nobody had ever heard of the people connected to Champion, but I liked the Ring Lardner story, and that’s the movie I wanted to do. Everyone thought I was crazy, of course, but I think I made the right decision.”

Never one to toe the line with synthetic, movie star-type parts, Douglas played classic heels in a number of films. In 1951, he showed a keen flair for portraying strong-minded characters like the sleazy newspaper reporter in Billy Wilder’s The Big Carnival (aka Ace in the Hole) and the sadistic cop in William Wyler’s Detective Story. He played more sympathetic types in Out of the Past (1947), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957) as Doc Holliday, Paths of Glory (1957) and The List of Adrian Messenger (1963).

Douglas was very particular in his role selection. “If I like a picture, I do it. I don’t stop to wonder if it’ll be successful or not,” he said in a 1982 interview. “I loved Lonely Are the Brave and Paths of Glory, but neither of them made a lot of money. No matter; I’m proud of them.”

His independent nature led him in 1955 to form his own independent film company, Bryna Productions. In the post-World War II era, Douglas was the first actor to take control of his career in this manner. Captaining his own ship, he soon launched a number of heady projects. Most auspiciously, he took a risk on a young Stanley Kubrick with Paths of Glory and Spartacus, films that feature two of Douglas’ finest performances. (He hired Kubrick for the latter after firing Anthony Mann a week into production.)

Indeed, Douglas backed his artistic and political opinions with action: His public announcement that blacklisted writer Trumbo would script Spartacus was a key moment in Hollywood’s re-acceptance of suspected communist figures.

During a Tonight Show appearance in August 1988 to promote his first book, The Ragman’s Son, Douglas told Johnny Carson that he often drew from personal experience for his work on film.

“What I found out when I wrote this book is I have a lot of anger in me,” he said. “I’m angry about things that happened many, many years ago. I think that anger has been a lot of the fuel that has helped me in whatever I’ve done.”