'HEREDITARY' WRITER/DIRECTOR "HAD A VERY HARD TIME SHAKING THOSE IMAGES"

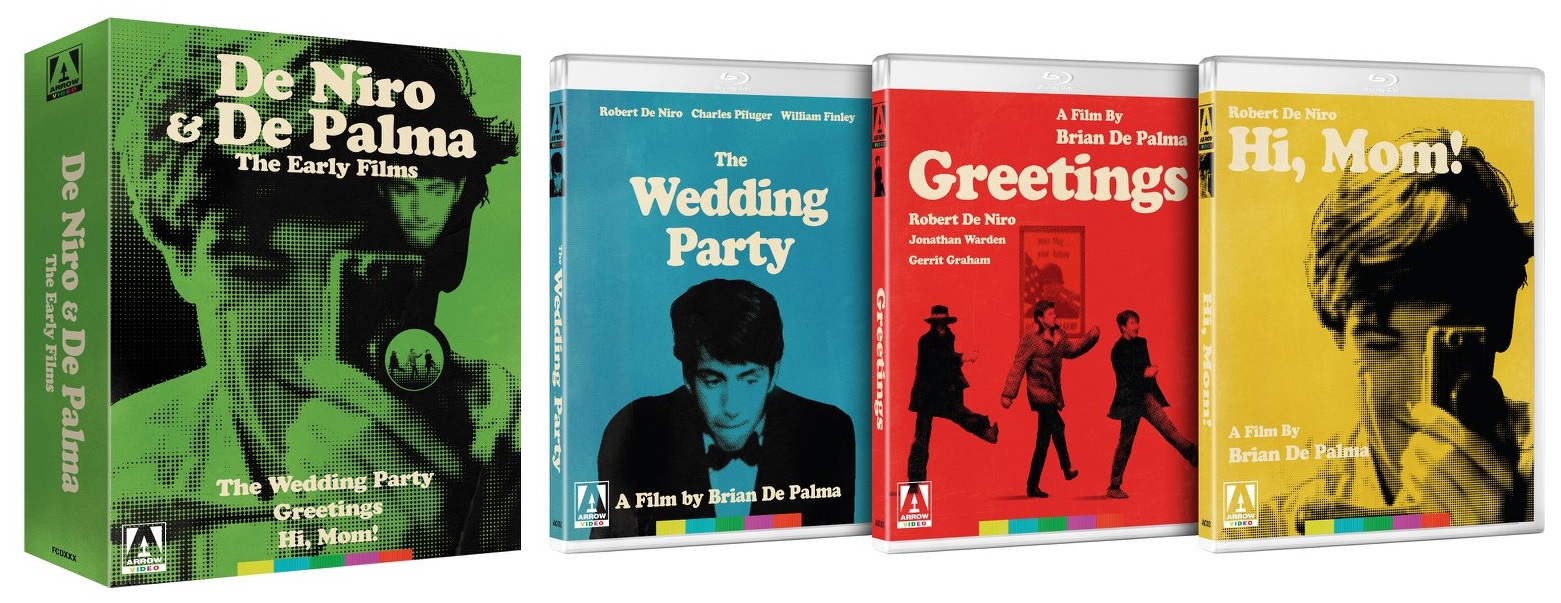

Ari Aster, the writer/director of Hereditary, tells South China Morning Post's James Mottram that Brian De Palma's Carrie was the first scary movie that "deeply affected" him. "I found the images were not leaving me and that really stuck with me for years,” Aster tells Mottram. "Sissy Spacek covered in blood with her bulging eyes … I had a very hard time shaking those images. It was definitely a film I was thinking about as I was writing this."

On the Blu-ray of Hereditary released today, Aster says that two of his main inspirations are Carrie and Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, & Her Lover. He discusses both of those films in a conversation with Scott Macaulay, from the summer 2018 issue of Filmmaker:

Filmmaker: What are some of your favorite horror movies?Aster: I love Rosemary’s Baby—there are some big nods to that at the end [of Hereditary]. I love Don’t Look Now, which I see this film as being a spiritual sibling to. Tonally, Nic Roeg is somebody whose films made a very serious impression on me from an early age. His sense of the elliptical is really, really fascinating to me. He has this amazing sense for the fragmentary—his films often play like memory. I love, on just the level of atmosphere, The Shining. I really love Jack Clayton’s film, The Innocents. There’s a long list of Japanese horror films that I love, like Kwaidan, Onibaba, Kuroneko, Empire of Passion and Ugetsu. And then, beyond Ugetsu, I just love Mizoguchi a lot. He’s somebody who I’m always thinking about. I was really taken with this brilliant South Korean film, The Wailing. I really liked The Witch. I can say that the goal with Hereditary was to make a horror film that I would want to see. I wanted to make a horror film that would scare me, and I wanted to root it in things that really trouble me and bother me.

Filmmaker: And what are those things?

Aster: What are my fears? [long silence] Just like everybody else, I would say I have fears of abandonment. I have fears of losing my quality of life, my body breaking down. I have fears of, if not abandonment, then losing somebody I care about because of something I have done. Fears of harming somebody in my life, be it intentionally or unintentionally. I have fears that I have no control over, like fears of disaster, which is more of a philosophical problem—like, my glass is half empty. I think a big part of the film is a fear of the intentions of others because, ultimately, it is a film about a conspiracy as seen from the perspective of the unknowing victims of that conspiracy.

Filmmaker: I was going to ask you whether you saw yourself in the teenage son character, but some of those fears you just listed are dispersed among the different characters. Fear of abandonment is referenced by the sister very early on.

Aster: Yeah. I see myself in all the characters, and none of the characters are surrogates for anybody in my family or myself. They’re all total inventions. It was just really important to me that I attend to the family drama first, and that I honor whoever those people were first, and then have all the horror elements emerge from that, and only if those elements were organic to the story and coming out of that dilemma at the heart of the film.

So often I’ll go to a horror film and there will be moments that get to me, and imagery I might find disturbing, but I feel let off the hook. Like, “OK, you get your spike of adrenaline. You go on the roller coaster, and you can leave. Don’t worry about it. You can brush off the experiences.” But the films that really stayed with me as a kid, that really haunted me, upset me—and they were the films I was always looking for and at the same time was always kind of hoping I wouldn’t [find because they] provoked feelings that I wasn’t able to immediately resolve as a kid—had maybe more of a malicious streak. I hated them as a kid because I hated what they did to me.

Filmmaker: Were those some of the ones you mentioned?

Aster: Well, no, actually. All of those I found to be really fun. The films that really upset me, I can’t even put on the list, somehow, because of my relationship to them.

Filmmaker: Can you say what some of them were?

Aster: Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, which isn’t technically a horror film, but it feels evil to me. Brian De Palma’s Carrie—I do love that film, but I saw it when I was 13. It didn’t really scare me while I was watching it, but later I was walking through the house in the dark to get water in the middle of the night, and I kept projecting images from that film onto the walls, which is what happened later with The Cook, The Thief. It was this masochistic thing, where once you’ve done it once, then your mind keeps reminding you to do it again. I’d race to get to my bed, and then I had a hard time going to the bathroom at night or getting water at night for a few years because I couldn’t trust myself to not project those images into the dark. Especially images from Carrie—Piper Laurie chasing her daughter around the house with this giddy, ecstatic smile on her face. That taps into something so primal.

Filmmaker: Is that the effect that you want this film to have on your audience?

Aster: I guess so. It’s funny, I screened The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover to the crew before I made The Strange Thing about the Johnsons but not before Hereditary. I was certainly thinking about that film, though, and especially the way that Peter Greenaway plays with artifice. I’ve always had a thing for Brechtian distancing effects. I feel that if they’re done well—if the story and performances are really compelling—then they make the film so much more vivid. Like, for instance, Dogville is a film that I’ll never shake, and I wonder what I would think of it if it were not set on a bare stage. The Cook, the Thief is this really, really monstrous vision of humanity. It’s so clinical, and all the characters are so remote, except for the one who’s the most vile. He’s the one character who is, to a certain degree, charismatic, who has any life, despite the fact that he is absolutely the grossest person ever depicted on screen. Everybody else feels like they are just a part of this tableau that Peter Greenaway is building. He was a painter before he became a filmmaker, and that’s very apparent. Even just down to Sacha Vierny’s very sickly, theatrical lighting, and those dollhouse sets where the colors are very rich but they’re also over rich—the colors themselves are getting sick. I know that film was rated NC-17 for tone. That makes total sense when you see the film because it is just feels evil.

Filmmaker: Your interest in Brechtian distancing effects is evidenced by the first shot of the movie, which sets up the camera as having this pitiless point-of-view on these tiny characters on a stage.

Aster: Yeah, the miniatures were sort of serving as a running metaphor for what’s happening in the film, which becomes very apparent by the end: These are people with no agency who are being manipulated by outside forces, like dolls in a dollhouse.

Sebastian Gutierrez's Elizabeth Harvest was released a couple of weeks ago, and is described by

Sebastian Gutierrez's Elizabeth Harvest was released a couple of weeks ago, and is described by  Soraya Secci, an actress from Cagliari, tells

Soraya Secci, an actress from Cagliari, tells