Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | December 2023 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Here's more from Falk's article, in which Guzmán and producer Michael Bregman look back at Carlito's Way, 30 years later:

“To my recollection Al Pacino and Eddie Torres both worked out at the same gym,” explains Michael Bregman, who produced the film alongside his father Martin. “He told Al he had a book, Al read it and I guess Al ran off and tried to make it a bunch of times, but it didn’t work out. And then he gave it to my dad who gave it to me.”The cast was rounded out by Penelope Ann Miller, John Leguizamo (who had to be convinced to do it, even though Benicio Del Toro was super-keen), Viggo Mortensen and Guzman as Carlito’s bodyguard Pachanga, while Sean Penn shocked people thanks to his balding perm as crooked lawyer Dave Kleinfeld.

“Within four minutes of the last shot and the gate being checked, he had walked into the hair and make-up trailer and shaved his own head,” laughs Bregman of Penn. “The AD almost had a heart attack.”

Brian De Palma, who of course had previous with Pacino having directed him in Scarface, was a comparatively late addition to the fold, with Abel Ferrara (Bad Lieutenant) initially attached.

“Abel had just done King of New York,” remembers Bregman. “That movie is stupendous. He’d shown up to meet my dad and I because he’d wanted to do a film about [porn star] John Holmes starring Christopher Walken.”

“He seemed like the right fit [for Carlito’s Way], but the temperament was not going to work at Universal Pictures,” he continues. “Abel’s an outlier and he has a certain way of working. It was a terrible parting of the ways because we’d become friends in the midst of it and then he wasn’t doing the movie and he went bats*** crazy. Then a year or so later we were pals again.”

Guzman recalls being “directed but not really” by Brian De Palma. The director had laughed during his audition, with the star not knowing whether that was a good thing until he arrived back home afterwards to find a message on his answering machine telling him he had the part. On-set, early in his career and keen to impress, the actor would ask the helmer whether he was on the right track and was normally rewarded with little more than a grunt. “He was a man of very few words,” says Guzman.

But for the actor, who had grown up Latino on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Carlito’s Way felt authentic to his blue-collar upbringing and former career as a social worker.

“Back in those days it was coke, alcohol, a lot of parties. A lot of girls,” he remembers. “We used to go clubbing and then you come back to the neighbourhood and there were these little social clubs. In the back of the social club there was always a pool table. That’s where s*** always started. That’s where I would find the people who exemplified the Pachangas of the world. Those guys were my reference.”

He continues, “The club scenes in Carlito, they were spot on. We had 300 of the best club dancers in New York City. In the holding area, it was like a party going on the whole time. People would bring their boom boxes. Instead of sitting around, it was fifty, sixty couples just dancing.”

Bregman recalls shooting in a pre-Guiliani New York that still reflected the grimier Big Apple of the 1970s when the film was set.

“We were lucky,” he says. “It still hadn’t metamorphosised and you could drop into the barrio and stuff structurally still existed. Subway stations in the outer boroughs still looked they did [20 years previously].”

[Brian De Palma] had managed to establish himself as promising, and as a promising director, he was entitled to the polite interest of at least one of the recurrent Hollywood new talent programs. In fact, he spent months sitting around the offices of Universal in New York with Charles Hirsch, the head of the studio's new talent programs. "Out of that frustration," he says, "smoking cigarettes and waiting for someone to return our calls, we came up with the idea for Greetings." Hirsch's title was grander than his power. He had been appointed because Universal thought he knew New York directors, and he might find some bright new filmmaker; but before Easy Rider's success it was hard to persuade the studio to take any of his recommendations seriously. When Greetings was made Universal kept its distance; its basic conservatism had always led it to consider new talent programs much as it would consider charm schools for aspiring starlets: decorative, but not functional. The film was started on 16mm, with $10,000 that Hirsch raised from his parents and from a friend of his parents. "We started to shoot," DePalma remembers, "but there was something wrong with the camera and everything came out a little soft. That took up a whole week of shooting, half our schedule. We looked at the material, and I said to Hirsch: "The worst thing about this is the way it looks. Let's go to 35mm." Fortunately, the laboratory scratched the first material we sent them, all the way through. They felt so badly about it, they gave us the rest of the film and the processing free."The film was made for $43,000; it took in more than $1 million. It brought DePalma general recognition for the first time. With his crew of eight, who were friends and students from New York University, he managed to make a virtue out of the limitations under which he was working. Purely for economy, he used very long takes. These tend to allow improvising actors to maunder on, but they also give the film a loose, episodic character that develops an exhilarating picture of the generation of 1968 and their particular problems and obsessions. Just because it was shot while the worries were real, it has a raw edge that later reconstruction cannot bring. The film's heart is the plan of three friends to help one of them evade the draft, the most immediate problem facing most of the people working on the film at the height of the Vietnam war in 1968. In its three episodes one man has to be kept awake all night so that he can be exhausted in mind and body when he goes before the draft board. The treatment is picaresque, a series of near hallucinatory encounters. In the second section DePalma returns to his constant obsession with the killing of President Kennedy; in a prolonged take he shows a would-be expert on the assassination tracing the path of the bullets across the naked body of his girlfriend. It is a repellent image which captures the weird erotic charge that talk of the Kennedy killing carries in necrophilic radio shows and publications. In the last section DePalma nods to the changes in sexual attitudes: one of his central characters is fascinated by pornography and is inventing a new form of art— peep-art. With all three components put together, sex, assassination, and the draft show a group of young Americans at a point of cultural transition. And they are shown in a context that is real, for Greetings is a street film, where the locations are exact and the extras are actually men who are to be drafted. Greetings becomes a report on the past.

This time the finished film did find a distributor. Frank Yablans saw it. He had not yet climbed his way to Paramount and The Godfather, and he was years away from his role as an independent producer at Twentieth Century-Fox, where he produced DePalma's The Fury. He was working with a small-time New York distributor called Sigma 3, which specialized in the sort of films that played art houses across the country. Yablans was excited by the film. He bellowed at his bosses: "If you don't pick up this film, I'm quitting." And, by himself, he stomped round the country to sell the film. DePalma still remembers his campaign with awe. "Literally," he said, "Yablans went from theater to theater with the print under his arm."

The film made money but DePalma saw little of it. It also won the Silver Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival. It was a critical success that was also marketable, largely on the peep-art sequences.

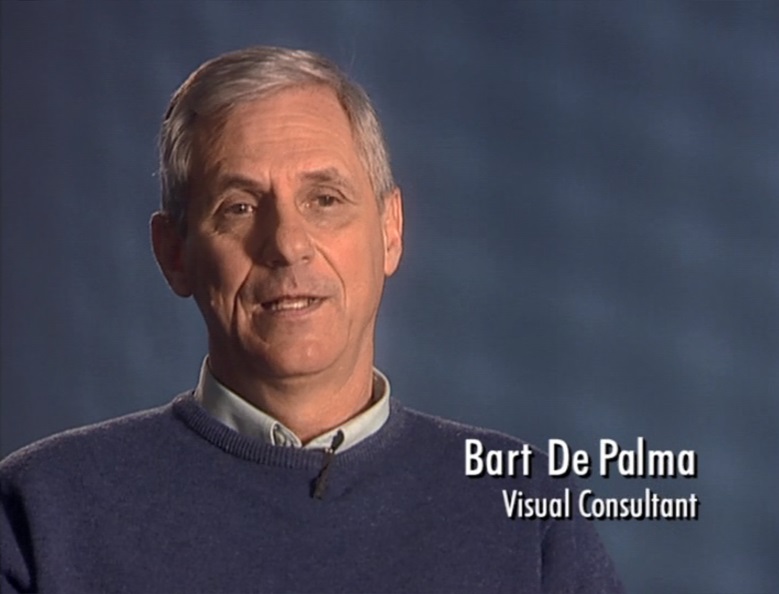

Bart's younger brother, Brian De Palma, had assisted Bart in making an experimental film in 1959, titled Gray Rain, while Bart was attending Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. Eleven years later, Bart assisted Brian in making Hi, Mom! (1970), and went on to work with Brian on Obsession (1976) and Femme Fatale (2002).

Bart's son, Cameron De Palma (who had appeared in Brian De Palma's Carrie), posted about his father last week on Facebook:

Barton De Palma, my father, passed away last friday in our home at 12:40pm, a couple of days after his 86th birthday. It has been an honor to care for him these months of joy and sadness and connection. He floated away gently, surrounded by his beloveds. Bart was always chasing and creating beauty, preparing for new adventures, making new friends. Until his liver decreed otherwise last year, he never grew old. I got to see this guy build televisions from scratch, train his telescope on the apollo craft as it went by, create new worlds on canvas, score touchdowns, have a family twice, photograph nebulas, scuba, assemble computers, become a gourmet chef, work in the movies, teach overseas, you get the idea…Unfillable shoes. Great love and respect for my incredible wife Dana, who befriended Bart and went above and beyond to hold us all up with love and grace ♥️.

In the book Double De Palma by Susan Dworkin, Brian is quoted, "I knew a lot about still photography from my science fair days. And I guess it was my brother Bart, he was taking a filmmaking course at Washington and Lee, and we made a little film at the shore."

HI, MOM!

On Hi, Mom!, Bart is credited as part of the N.I.T. Journal crew (along with Bettina Kugel/Tina Hirsch and two others), and he is also credited as still photographer.

OBSESSION

For Obsession, Bart painted the portraits that are seen in the film, and he also took the photos that are used in the film's opening slideshow.

FEMME FATALE

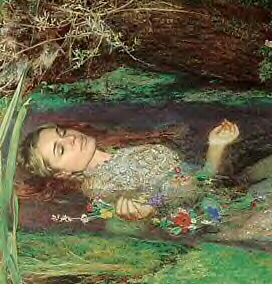

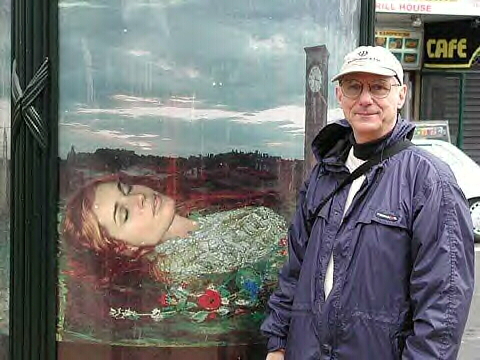

For Femme Fatale, Bart makes a cameo as a security guard, and was also a visual consultant - he created the "Déjà Vu" poster of Rebecca-as-Ophelia, and took 3200 photos during the making of the film to make up the photo mural seen in the apartment of Antonio Banderas' character. (Interestingly, Déjà Vu was also the working title of Obsession.) Bart appears on screen in one of the Laurent Bouzereau special feature documentaries on the Femme Fatale DVD:

My job on Femme Fatale was to produce the photographic work that Antonio was going to create in the course of the film. When Antonio read the script, he was bothered by the fact that the character was a paparazzi, something that he apparently has considerable dislike for. The interesting thing was, once he saw the montage that we were creating for his character, he said to Brian, “Now I understand. Now I understand what this person is, and who this person is.” I figured out when I was done, I shot 3200 photographs of this location. And I must say that many people on the production crew bent over backwards to work on this picture just because they wanted the opportunity to work with somebody who was going to make it technically interesting for them, and interesting visually.

The film’s producers had intended to shoot almost all of Scarface in Miami.L.A. Taco“I was the first guy [from the production] in Miami, and I was supposed to set up the entire movie there,” says Scarface executive producer Louis Stroller.

But some Miami columnists and politicians were highly critical of the storyline, and the controversies surrounding the filming of Scarface garnered numerous headlines before production started.

“Miami was and still is very well-to-do, and there were a lot of bankers and lawyers, and they didn’t want to point to Miami as a place where all bad Cubans went,” Stroller tells L.A. TACO. “So they put pressure on and pressure on until, finally, the studio called and said, ‘No, we’re not going to make the movie in Florida at all. If we’re going to make this movie, it’s going to come back to L.A.’”

At the end of the day, community leaders were likely feeling the loss of the economic impact that comes from a major studio production. Constituents were also applying the pressure, as a number of local Cuban actors that were supportive of the film showed up at town hall meetings focused on the production.

Eventually, leaders of Miami’s Cuban-American community welcomed back the filmmakers, though they were still not thrilled about the main character being a Mariel criminal.

Stroller says they were permitted to return because the production wasn’t going to shoot any scenes in Miami that were detrimental to the area.

The producers also agreed to include a disclaimer at the end of the film stating that Scarface did not represent the Cuban-American community as a whole.

Over ten days, with bodyguards in tow, De Palma shot mostly exteriors that best captured Miami’s modern, Art Deco, and tropical aesthetics.

Aside from the film’s pressure-cooker car-bomb-gone-awry sequence filmed in New York, and the exterior of Tony’s Miami compound and Alejandro Sosa’s Bolivian estate, which were both shot in Santa Barbara, much of the nearly three-hour film was shot between practical L.A. locations and sets built on-stage at Universal Studios.

Stroller gives a lot of the credit to Scarface’s visual consultant, Ferdinando Scarfiotti, for capturing the look of Miami in L.A.

“He went back to L.A. and scouted all the places and he came up with some wonderful locations,” says Stroller. “He was very inventive.”

Unfortunately, 40 years later there aren’t many folks from the production who can comment with first-hand knowledge on the film’s locations, even Stroller.

“It was a few days ago,” he quips.

De Palma could not be reached for comment for this article.

Scarfiotti, producer Martin Bregman, art director Edward Richardson, cinematographer John Alonzo, and location manager Frank Pierson, who may have had some insight on the film’s locations, have since passed away.

One location manager who worked on the Florida locales declined to comment on the move from Miami to L.A.

Co-producer Peter Saphier told us he wasn’t close enough to the actual filming - he mainly dealt with Bregman, Stroller, and Universal executives - to say why and how the L.A. locations were chosen.

With all that in mind, L.A. TACO took a photographic look at a number of the L.A. spots from one of the most polarizing yet hugely influential gangster pictures ever made.