FRANK YABLANS "WENT FROM THEATER TO THEATER WITH THE PRINT UNDER HIS ARM"

Excerpt from the 1979 book The Movie Brats, by Michael Pye and Lynda Myles:

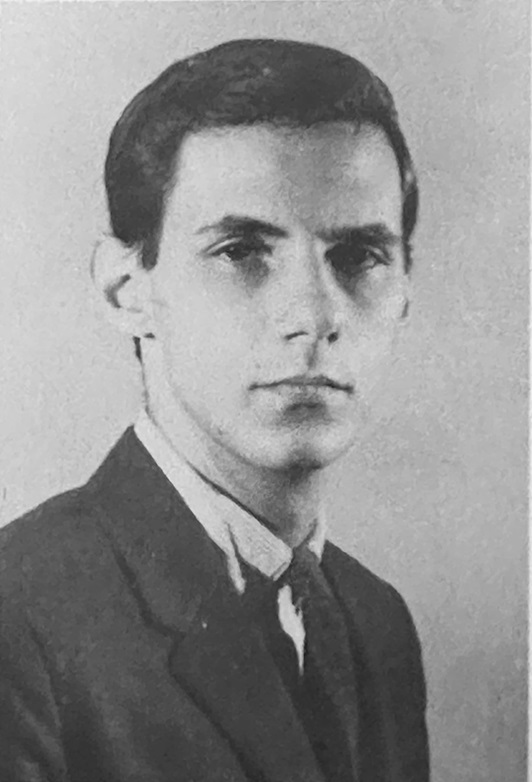

[Brian De Palma] had managed to establish himself as promising, and as a promising director, he was entitled to the polite interest of at least one of the recurrent Hollywood new talent programs. In fact, he spent months sitting around the offices of Universal in New York with Charles Hirsch, the head of the studio's new talent programs. "Out of that frustration," he says, "smoking cigarettes and waiting for someone to return our calls, we came up with the idea for Greetings." Hirsch's title was grander than his power. He had been appointed because Universal thought he knew New York directors, and he might find some bright new filmmaker; but before Easy Rider's success it was hard to persuade the studio to take any of his recommendations seriously. When Greetings was made Universal kept its distance; its basic conservatism had always led it to consider new talent programs much as it would consider charm schools for aspiring starlets: decorative, but not functional. The film was started on 16mm, with $10,000 that Hirsch raised from his parents and from a friend of his parents. "We started to shoot," DePalma remembers, "but there was something wrong with the camera and everything came out a little soft. That took up a whole week of shooting, half our schedule. We looked at the material, and I said to Hirsch: "The worst thing about this is the way it looks. Let's go to 35mm." Fortunately, the laboratory scratched the first material we sent them, all the way through. They felt so badly about it, they gave us the rest of the film and the processing free."The film was made for $43,000; it took in more than $1 million. It brought DePalma general recognition for the first time. With his crew of eight, who were friends and students from New York University, he managed to make a virtue out of the limitations under which he was working. Purely for economy, he used very long takes. These tend to allow improvising actors to maunder on, but they also give the film a loose, episodic character that develops an exhilarating picture of the generation of 1968 and their particular problems and obsessions. Just because it was shot while the worries were real, it has a raw edge that later reconstruction cannot bring. The film's heart is the plan of three friends to help one of them evade the draft, the most immediate problem facing most of the people working on the film at the height of the Vietnam war in 1968. In its three episodes one man has to be kept awake all night so that he can be exhausted in mind and body when he goes before the draft board. The treatment is picaresque, a series of near hallucinatory encounters. In the second section DePalma returns to his constant obsession with the killing of President Kennedy; in a prolonged take he shows a would-be expert on the assassination tracing the path of the bullets across the naked body of his girlfriend. It is a repellent image which captures the weird erotic charge that talk of the Kennedy killing carries in necrophilic radio shows and publications. In the last section DePalma nods to the changes in sexual attitudes: one of his central characters is fascinated by pornography and is inventing a new form of art— peep-art. With all three components put together, sex, assassination, and the draft show a group of young Americans at a point of cultural transition. And they are shown in a context that is real, for Greetings is a street film, where the locations are exact and the extras are actually men who are to be drafted. Greetings becomes a report on the past.

This time the finished film did find a distributor. Frank Yablans saw it. He had not yet climbed his way to Paramount and The Godfather, and he was years away from his role as an independent producer at Twentieth Century-Fox, where he produced DePalma's The Fury. He was working with a small-time New York distributor called Sigma 3, which specialized in the sort of films that played art houses across the country. Yablans was excited by the film. He bellowed at his bosses: "If you don't pick up this film, I'm quitting." And, by himself, he stomped round the country to sell the film. DePalma still remembers his campaign with awe. "Literally," he said, "Yablans went from theater to theater with the print under his arm."

The film made money but DePalma saw little of it. It also won the Silver Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival. It was a critical success that was also marketable, largely on the peep-art sequences.