PRIOR TO UPCOMING AUCTION, COSTUME DESIGNER RECALLS WORKING ON IT WITH WILLIAM FINLEY, ETC.

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | October 2023 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Known for her role as Angelique on the ABC soap opera Dark Shadows, on which she appeared from 1967 to its final episode in 1971, Parker worked on Hi, Mom during a production break. Having scripted lines to read on a daily soap opera, Parker was not accustomed to the improvisatory nature of De Palma's film. In a 2016 interview with Den of Geek's Tony Sokol, Parker said, "Brian De Palma cast me and they actually put in my two children. He was doing improvised theater. We were improvising on film, without lines, without a character to play. It was a whole different thing and I actually was not very good at it." Parker had a bathtub scene that De Palma had asked her to improvise, but it ended up being cut from the film. "I was very naive and not very courageous," Parker said in 2013. "He wanted me to improvise sexual fantasies ... in a bathtub … with bubbles … in the nude."

In an interview conducted after only the first day of filming, De Palma described the housewife character for Joseph Gelmis, in Gelmis' book, The Film Director as Superstar:

I got the idea for a housewife making a film diary of her life from David Holzman's Diary. She starts out with home movies. It gets more and more obsessive. She's very concerned with things. She has a scene where she talks about her body the way she talks about chairs and objects. Everything becomes an object for her.

Here's an excerpt from the Hollywood Reporter obituary by Mike Barnes:

Mere days after arriving in New York in 1967, the green-eyed Parker auditioned for Dark Shadows creator Dan Curtis, who cast her as Angelique in a story arc that would detail the origin of the tortured vampire Barnabas.A soldier and the son of a shipping magnate, Barnabas in 1795 seduced and abandoned a servant girl from Martinique not realizing she was a witch. That girl was Angelique. “He just dallied with her and then dismissed her, and she was not to be dismissed,” Parker said in an undated interview for a Dark Shadows home video release.

An enraged Angelique would damn Barnabas to enteral life as a vampire, kicking off a battle between the two that would continue through different time periods.

“I played her as somebody who was much more of a tragic figure, who was desperately, desperately in love,” Parker said in 2016. “And her heart was broken. That’s much more sympathetic than just being a mean old witch. I felt that her acts were acts of desperation, not acts of evil.”

Though Angelique and others she would inhabit would perish, she would remain with the daytime serial through its April 1971 demise.

“Dan Curtis [would call Parker and say], ‘You’ve been great, kiddo, but we’re going to kill your character. Thanks a lot for everything,” she recalled in 2020. “Of course I was very sad, but about two months later they called me and said that they wanted me back.

“We were kind of the first team, and the fans seemed to watch it more when Angelique and Barnabas were fighting it out. That seemed to be the most popular part of the show, so [Curtis] brought me back many, many times.”

Parker was born Mary Lamar Rickey on Oct. 27, 1938, in Knoxville, Tennessee. Her father, Albert, was an attorney, and her mother, Ann, was active in civic groups.

She graduated from Central High School in Memphis and attended Vassar — she roomed with Jane Fonda there — and Rhodes College in Memphis, where at 19 she served as Wink Martindale’s assistant on his WHBQ-TV show, Dance Party. She then earned a master’s degree from the University of Iowa.

After a busy summer acting at the Millbrook Playhouse in Pennsylvania, Parker left her husband and two kids in Wisconsin for a spell to see if she could find work as an actor in New York. “By the time the children were 6 and 7 years old,” she said in a 1972 interview for Mid-South magazine, “I knew that I just couldn’t sit there and look at those fields for the rest of my life.”

In New York for her second-ever professional audition, she was cast as Angelique. “I think my only reaction to it was paralyzed fear,” she said.

Dark Shadows, which had debuted in June 1966, received a viewership jolt when Frid was introduced as Barnabas in April 1967. Parker arrived in the fictional town of Collinsport, Maine, seven months later.

“We realized [the show] was popular,” she said. “Everywhere we went [the cast was] recognized. There was a huge crowd outside the [Manhattan] studio when we finished in the afternoon of autograph seekers. People would show up, the same people every single day, day after day. They worshipped some of us and would walk us to the subway.

“I can remember standing on the subway when school got out and seeing 200 or 300 kids all waiting to take the train. They would see me and start screaming and run to the other end of the platform! They were so terrified because I was so evil.”

Meanwhile, feminists admired Parker because of her character’s strength, she said. “She was coming in at the beginning of the women’s movement and she was very independent,” Parker noted. “They sort of missed the fact that she was obsessed with her love for Barnabas and that was destroying her.”

On Facebook, her Dark Shadows co-star Kathryn Leigh Scott wrote Monday that Parker’s death left her “heartbroken, as all of us are who knew and loved her. She graced our lives with her beauty and talent, and we are all richer for having had her in our lives.”

During breaks in production, Parker acted on Broadway in September 1968 in Woman Is My Idea, which lasted just five performances, and in the early Brian De Palma film Hi, Mom! (1970), starring Robert De Niro.

Piper Laurie, the three-time Oscar-nominated actress known for her performances in The Hustler and Carrie and for her outlandish two-character, two-gender turn on the original Twin Peaks, died Saturday morning in Los Angeles. She was 91.Laurie had not been well for some time, her rep, Marion Rosenberg, told The Hollywood Reporter.

In Lee Gambin's book, Like Being on Mars: An Oral History of Carrie (1976), Laurie says that she "absolutely used immense amounts of stagecraft with the role" of Margaret White. "I think it definitely needed to go there, to get to those operatic and grandiose theatrical levels. I watched Brian's movie Phantom Of The Paradise a few times before doing Carrie, and I saw how operatic and over the top that was! So subconsciously I think I gave myself permission to be over the top and larger than life. I think that benefits such a wonderfully operatic story. It is really an extension of a heightened reality!"

Regarding Laurie's time on Twin Peaks, Barnes writes:

After Laurie’s unscrupulous Catherine Martell of the Packard Sawmill presumably had perished in a fire during the first season of ABC’s Twin Peaks, series co-creator David Lynch called her and said he wanted the actress to return for season two — to play Martell disguised as a man.“‘What kind of man is going to be up to you,'” she said he told her. “‘You could be a Mexican, a Frenchman, whatever you think.’ I was beside myself with the power to be able to pick my part like that. I decided I would be a Japanese businessman because I thought it would be less predictable.”

Incredibly, the cast and crew were kept in the dark about this. Laurie was told not to tell anyone — not even her family — that she was back on Twin Peaks, and her name was kept out of the credits. And so, sporting a black hairpiece, Fu Manchu mustache and dark glasses, Laurie arrived on the set as actor Fumio Yamaguchi, there to portray the character Mr. Tojamura.

“The cast would never come very close to me,” Laurie said. “They were told to be respectful to this actor who had come over from Japan specifically for the show and had only worked with [Akira] Kurosawa.”

She said that, eventually, some in the cast began to realize something was amiss — but Peggy Lipton, Laurie noted, thought Yamaguchi was actually Isabella Rossellini in disguise.

The actress earned Emmy noms in 1990 and 1991 for her work on the show.

From Dan Callahan's tribute to Piper Laurie at RogerEbert.com:

Thoughts about Piper Laurie must begin with the darkness and throatiness of her mature speaking voice and the frightening directness and strength of her gaze, which could seem nearly Satanic sometimes, as if she were intimately aware of all the worst that life had to offer. She had been born Rosetta Jacobs to Jewish parents in Detroit, and it was only after signing a contract at Universal that she got her new name. Laurie never thought seriously of discarding that name from her ingenue days, even when its incongruous birdlike cheerfulness became so at odds with the watchful quality she was so apt to offer to the camera, with its hints of unspeakable depravity.In the 1950s, Universal put out lots of cockamamie press stories about its young starlet; in one of them, the young Laurie supposedly only ate flower petals. In her colorfully indiscreet 2011 memoir “Learning to Live Out Loud,” Laurie writes of how she lost her virginity to future-president Ronald Reagan after they starred together in a movie called “Louisa” (1950), and she is unsparing about how coldly technical and un-romantic this was (she claimed that Reagan even told her how much money he spent on condoms). Laurie made pictures with Tony Curtis and Rock Hudson and looked pretty in Technicolor, but only those watching very closely may have discerned that there was something more to her than what Universal required, something like a bomb that needed to go off.

By the late 1950s, Laurie was fed up with Hollywood and went to New York to study acting. It wasn’t easy to live down her past or get casting agents and directors to take her seriously, but Laurie made a serious impression on live TV when she played an alcoholic in “Days of Wine and Roses” (1958) for director John Frankenheimer. This eventually led to her getting the role of Sarah Packard in Robert Rossen’s “The Hustler” (1961) opposite Paul Newman, a performance that earned her an Academy Award nomination for best actress and put Laurie on a new level.

Laurie’s Sarah Packard is an alcoholic, and she walks with a limp. Any man with sense would know right away that Sarah is trouble with a capital “T,” and she tells Newman’s “Fast” Eddie Felson to his face that she is trouble, and a bad lot, and not worth bothering about. But Sarah Packard has a kind of allure in her consummate solitude; there is something somehow glamorous even about her self-loathing.

How does Sarah earn her living? Sarah tells Eddie that she is living off what the last rich man she was with gave her, and so she has been around the block more than a few times. When she was younger, Sarah had tried to be an actress, but that’s all finished; now she mainly drinks and broods. When she isn’t drinking, Sarah takes college classes, but without any ultimate aim in mind. The look on Sarah’s face is so isolated and so self-destructive that it is as if ultimate aims are beneath her. She hates herself so much that there is something untouchably romantic about her.

“The Hustler” remorselessly charts the hopes that begin to grow in Sarah that she might actually deign to accept the love of another human being and then their final destruction when she enters the orbit of Bert Gordon (George C. Scott), a man who wants to exploit Eddie’s talent for pool playing and sees Sarah as an encumbrance. Bert says things meant to wound Sarah, and she begins to crumble away. There comes a point when Bert whispers something in Sarah’s ear, and we never find out what it was, but it is so bad that she is finished by it; she cannot go on any further.

Laurie’s Sarah Packard is a woman who once had many possibilities, and she still has them almost up to the end; all it takes is one more bit of deliberate cruelty to destroy her, and Scott’s Bert Gordon tips that scale for her. This is tragic, because Sarah Packard isn’t the sort of person who is a hopeless case, but she is too sensitive, and she is also perverse, and that is a deadly combination.

Laurie did not capitalize on her success in “The Hustler.” Instead, she married the film critic Joe Morgenstern and didn’t make any more movies until she was offered the role of the religious fanatic mother Margaret White in Brian De Palma’s “Carrie” (1976), in which she gives one of the campiest performances of all time even though Laurie plays it all with such a straight face. It was that poker face of hers that let Laurie get away with anything in this movie and somehow still seem serious and seriously scary, even when Margaret speaks of the “dirty pillows” of her daughter Carrie (Sissy Spacek) and runs around smiling with a large knife, her long, curly hair flowing behind her.

“Carrie” brought Laurie another Oscar nomination, this time for best supporting actress, and Laurie obtained far more work now after this second comeback. She headlined a horror vehicle for director Curtis Harrington called “Ruby” (1977), played Judy Garland’s fearsome stage mother on television in 1978, and was flat-out terrifying as Magda Goebbels in “The Bunker” (1981), especially in the scene where she poisons her own children.

But Laurie gave maybe her most perverse performance of all as a well-to-do woman who develops a yen for a mentally handicapped young hunk (Mel Gibson) in “Tim” (1979), which is meant to be a sentimental love story but is steered directly into the most disturbing possible direction by Laurie from the moment her character first sets eyes on her young prey in his tight shorts (in her memoir, Laurie wrote that she slept with Gibson shortly after the shooting wrapped, for she wasn’t shy about detailing such perks of her profession).

Laurie worked quite a bit in the 1980s, getting one more Oscar nomination for “Children of a Lesser God” (1986) in the supporting category. But it was in 1990 that she received a role that will stand with her Sarah Packard and her Margaret White for her legacy: the authoritative Catherine Martell on David Lynch’s classic surreal TV series “Twin Peaks,” an unscrupulous lady who will stop at nothing to get what she wants, the inverse of the romantic loser Sarah Packard.

Chicago-based Japanese American multi-instrumentalist Sen Morimoto is releasing his third studio album, Diagnosis, on November 3 via City Slang, in partnership with his own Sooper Records. Now he has shared another song from it, “Deeper.” Listen below, followed by his upcoming tour dates.Morimoto had this to say about the song in a press release: “There is a place in the center of my chest, tucked behind my heart, where only the most extreme depths of grief or joy make themselves known. When the context of everything in your life is squeezed into a single moment by the pressure of an overwhelming present it feels like you’re at the bottom of the ocean. Nothing’s deeper.”

On Sunday, October 22, fans will be able to hear the album early at a drive-in movie theater in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood. All the album’s music videos will also be shown, as well as the cult 1974 horror rock opera Phantom of the Paradise, which was directed by Brian De Palma and is an influence on the new album.

Morimoto explains: “Phantom of the Paradise was a film my collaborators New Trash [production company in Chicago] recommended when I came to them with the concept for the ‘Diagnosis’ video. I couldn’t believe I’d never seen this amazing rock opera that poked fun at capitalism and corruption in the music industry in a way that felt so related to what Diagnosis is about. It lives in the same goofy fantasy horror world that I wanted our visuals to come from too so I was immediately obsessed.”

RSVP to the drive-in event here.

They chat about De Palma’s ability to elevate a B-Grade thriller to A-Grade material through his master craftmanship. His use of split screen and split diopter, and dialogue free scenes to show and not tell the audience the characters movements.They gush about De Palma being one of their all time favourite directors (Felicia’s top favourite director? Maybe, probably!), and how deliberately frames each scene, and how no one is able to pace a story like him.

Felicia: The tagline for Dressed To Kill is, “Every nightmare has a beginning – this one never ends.” That’s funny. It makes it sound like it’s an extreme slasher movie.Eugina: It does.

Felicia: I mean, technically, there are slasher elements, but it’s more of a cerebral thriller.

Eugina: As far as movies from that era go, it’s, like, slick. It’s very aesthetically pleasing, kind of. Not really like a grimy slasher film, it’s very polished and classy. Kind of a classy De Palma.

Felicia: Right? And I love you for that, because some people kind of describe him as “sleazy,” and I’m like, I don’t think he’s sleazy. He makes stuff that I think is in the back of everyone’s fantasies, and he’s just putting it out there. But it’s so beautiful to watch. His films are beautiful. They’re not sleazy, they’re not gross.

Eugina: No, it’s crafted very well.

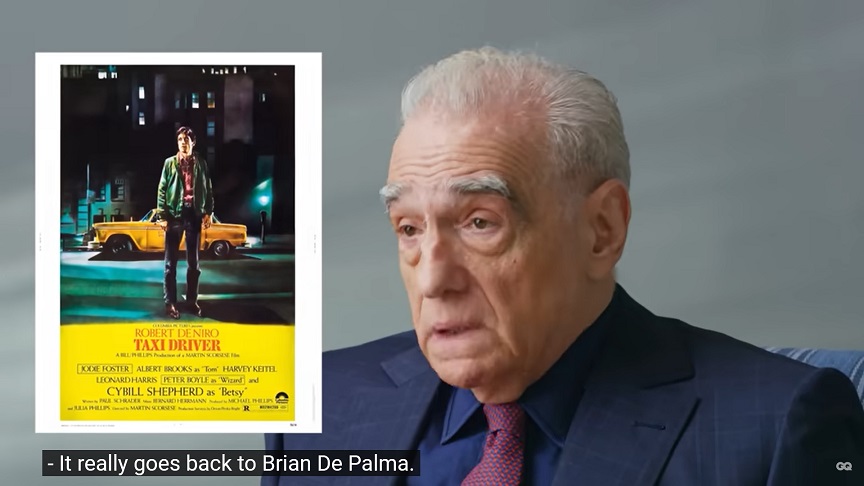

Taxi Driver – it really goes back to Brian De Palma, his independent cinema – and Hollywood started saying, "Hey, maybe these indie films, these kids could work in the industry." And so we were all out in L.A., and he introduced me to Paul Schrader. Schrader wrote Taxi Driver. Travis comes from his vision, but more psyche. I connected with it through Dostoyevsky’s Notes From Underground. It was, like, enlightening, you know? And so, for me, when I read the script, Brian gave it to me. He said, You know, I don’t want to do it – I can’t do it, but maybe you should do it. But I didn’t have enough cache, as they say, at that time, to make the picture. But then they saw the rough cut of Mean Streets, and they changed their mind—especially when they saw De Niro in it. And so they said, For the two of you, we could probably get this film made.

Meanwhile, earlier this week, American Film Institute put a spotlight on Scorsese's Mean Streets for that film's 50th anniversary:

Scorsese told a group of AFI Fellows during a Conservatory seminar in 1975 that he encouraged his actors to improvise during rehearsals, which he transcribed from audio tapes to include in the script. As one example, the scene in which Johnny Boy delivers a long monologue to Charlie about why he cannot make that week’s payment to Michael was originally entirely improvised by De Niro and Keitel, according to Scorsese. The sequence was the last to be filmed, after Scorsese pleaded with his producers for another day to be added to the shooting schedule. He mentioned in the seminar that he edited the picture but did not receive onscreen credit due to DGA regulations. Also participating in post-production were filmmaker Brian De Palma and Sandra Weintraub, who Scorsese was romantically involved with at the time. Scorsese told AFI fellows in 1975 that he was working with Mardik Martin on a sequel to MEAN STREETS.

Scorsese admits that he had trouble editing the last sequence of Mean Streets and got some advice from Sid Levin, who receives credit on screen for shaping the whole film. Scorsese maintains, however, that the rest of the film is his work as an editor: "Sid didn't cut it; I cut it. Sid came in and showed me and made an initial cut in the last section where they're singing 'O Marienello' at the end, which is the traditional song that ends all the Italian festivals. . . . At that point, I couldn't cut it. It was five months editing and I was really freaked. The rest of it I cut. Brian De Palma came in and Sandy Weintraub.

Like many French filmmakers before him, Sébastien Marnier fell in love with cinema through Hollywood movies. Thrillers like “Basic Instinct,” “Fatal Attraction” and “Single White Female” made a big impact on him as a teenager. They were exciting, usually featured strong and dangerous women at the heart of them and, of course, they were sexy, which at 14 or 15 was a “really big deal,” he laughed in a recent interview.“American cinema is really the foundation of my cinephilia,” Marnier said through a translator. “What I like to look for is finding that feeling that American film gave me when I was a teenager, but making a truly French film with those feelings. So how do I take the inspiration that I felt as a teenager from those emotions to make a truly French film that is taking place on the French territory?”

With “The Origin of Evil” he wanted to pay homage to those films and put them within a distinctly French context. Influences range from Claude Chabrol to “Parasite.” A playful mixture of genres, it’s scary at times, but also funny, offbeat and, yes, sexy, as Stéphane, who is in a romantic relationship with a volatile imprisoned woman, navigates the personalities in her father Serge’s (Jacques Weber) orbit: His spendy wife Louise (Dominique Blanc), his daughter George (Doria Tillier) who is angling to push him out of the business, a jaded granddaughter (Céleste Brunnquell) and their unfriendly maid (Véronique Ruggia).

Though the origin of this story comes from a very personal place — Marnier's mother, who made contact with her father later in life — he hopes it has broader commentary on issues affecting modern France.

“I think ‘The Origin of Evil’ talks about the end of a certain French society, the end of a powerful patriarchy, the end of a super-rich right wing dominant class, especially in the Riviera, a very rich class that was anti-Semitic and extremely powerful,” said Marnier. “And it’s in this confrontation of two worlds that we find a tension that France, is really experiencing at the moment. There’s something very French, I think, in the way the film captures the class struggle.”

It’s also a film where no one is quite what they seem, and it keeps you guessing and second guessing until the very end. Instrumental in this was the casting of Calamy.

“She has something that’s quite rare in French cinema, which is that she’s very beautiful and sexy, but on the other hand, she’s also banal in the good sense of the word. She’s really the woman next door,” Marnier said. “And because of things like ‘Call My Agent!,’ we like her. We have an empathy for her.

"If I had cast Isabelle Huppert, we would know right away that she was going to kill everybody,” he added.

Stéphane, it should be said, does not “kill everybody,” but she has her dark secrets too.

Of that De Palma comparison, Marnier deflects. It is, he said, much too much. “I don’t deserve that,” he said. “He’s one of my favorite filmmakers.”

He’s mostly just excited that after a few films, he’s finally got one that’s playing in American cinemas too.

“It’s really moving and beautiful,” he said. “My other films were released on platforms in the U.S., but to be released theatrically is a great gift.”

Craig D. Lindsey, Nashville Scene:

The Origin of Evil is practically two hours of Sébastien Marnier declaring that Brian De Palma is one of his favorite filmmakers.The French director works many of the psychological-thriller legend’s tricks into his psychological thriller: overhead shots, slow dissolves, split-screen sequences. Hell, the movie even begins with the camera lecherously roving around a women’s locker room, much like the salacious opening sequence from De Palma’s Carrie, set in a girls’ locker room.

Like in most De Palma thrillers, we also have a mysterious female protagonist. Stéphane (Laure Calamy) is a fish-plant worker who gets reacquainted with her wealthy father (Jacques Weber), whom she didn’t grow up with. Of course, when she visits the old man at his swanky (and cluttered) Mediterranean mansion, she’s greeted by a family who’s just as off-putting as she is. The business-minded daughter (Doria Tillier, gloriously icy) wants Stéphane gone the minute she meets her, while the chain-smoking matriarch (a vainglorious Dominique Blanc) is too busy being a compulsive shopaholic to incite much animosity. The business-minded daughter’s daughter (Céleste Brunnquell) is mostly around taking pictures, hoping to escape this poisoned clan she’s unfortunately bound to by blood.

With the old man ailing after a stroke and the fam ready to carry on his business without him, Stéphane — who’s ready to do anything for her daddy — has come along at the right time. Of course, we learn in the second hour that Stéphane, who has a girlfriend (Xavier Dolan regular Suzanne Clément) in prison, has some hidden motives of her own.

Evil is basically a tribute to eat-the-rich thrillers made by French filmmakers. (De Palma, who has famously divided his time between New York and Paris, is considered an honorary Frenchman.) Along with De Palma, you also get whiffs of Claude Chabrol and René Clément, two Frenchmen who have done adaptations of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley — which should tell you exactly what you’ll get with this flick. Fans of Succession may also get a kick out of the so-deranged-it’s-funny family politics that pop off when Stéphane arrives. Weber’s devious, ambiguously depraved dad certainly gives Brian Cox’s Logan Roy a run for his money in the piece-of-shit-patriarch department.

Then that big twist happens, and “Origin of Evil” becomes a deliciously wild thriller in the vein of Brian De Palma or the late French suspense filmmaker Claude Chabrol, as we try to figure out who is really manipulating who.Marnier tightens the screws of the plot as things unravel, using attention-calling filmmaking techniques to heighten the suspense, like sudden zooms and organ music on the score by Pierre Lapointe. He even deploys split-screen views in a clear De Palma homage, at one time breaking the screen into five points of view.

Calamy keeps us guessing as to Stéphane’s motives, concealing layers of complexity beneath her seemingly guileless exterior. And Blanc is a riot as the Norma Desmond-esque Louise, who wears expensive furs to the breakfast table and seems to be enjoying the skullduggery in her house almost as much as the audience is.

Watching “The Origin of Evil,” we keep changing our minds about who we should be rooting for, but in the end just root for a good time at the movies. And we certainly get one.

Sébastien Marnier’s The Origin of Evil is a thriller with scant thrills but plenty of echoes of better, more explosive works. It opens with a slow-motion tracking shot of young women inside a locker room in various states of undress, but rather than land on a showering teenager being horrified by her womanhood, as in Brian De Palma’s Carrie, the camera stops on the upturned face of Stéphane (Laure Calamy). It’s a naked allusion and nothing else. To wit, the film’s later, recurring use of split-screen—another staple of De Palma’s voyeuristic cinema—exudes a visual anonymity, as if Marnier were working from a checklist.

An article posted by Vulture's Jen Chaney on October 3rd notes that the kaleidoscopic collage is an art installation by Marco Brambilla, titled King Size:

Many of the people in the heavily Gen-X crowd responded to all the techy pageantry the way everyone responds to concerts in 2023: by whipping out their phones to film it. “I don’t record music at concerts,” Haygood told me. “I recorded two minutes and 33 seconds of that.” He’s referring to the Achtung Baby rollicker “Even Better Than the Real Thing,” a song accompanied by the art installation King Size, a kaleidoscopic collage of images of Vegas and clips of Elvis Presley created by artist Marco Brambilla that scrolls from the back of Sphere to its front. The movement of the video creates the optical illusion that the stage and the standing general-admission crowd around it are rising upward, a sensation unlike anything I have ever experienced. (In one video posted on YouTube, you can hear a guy in the crowd shouting incredulously, “Oh my God, we’re moving!”)But this isn’t just eye-candy gimmickry. The King Size segment, a callback of sorts to the rolling camerawork in the music video for “Even Better Than the Real Thing,” also functions, like so much of what U2 was doing during their Achtung Baby period — where Bono routinely used a remote control onstage to channel-surf through the muck of 1990s broadcast television — as a commentary on oversaturation. “It’s exactly what some of my work is about, which is this idea of the seduction of the spectacle,” Brambilla told me prior to Sphere’s opening. “Is it going to destroy us? Is it going to make us better or worse?”

Coming-of-age films are often about teenage girls making an awkward transition into womanhood, and the potency of Brian De Palma’s pulpy shocker, adapted from the novel by Stephen King, lies in its supernatural manifestation of familiar agonies. From the beginning, “Carrie” aligns itself with a misfit daughter (Sissy Spacek) of a Bible-thumping mother (Piper Laurie), who grows into violent telekinetic powers that she has trouble controlling, especially when prodded by classmates. When her anguish turns prom night into a gruesome affair, De Palma and Spacek pull off the neat trick of holding our sympathies as her psychic pain is unleashed.