and a run of celebrated directors transformed a Sixties TV series into a blockbuster franchise" - here's an excerpt:

Over the last three decades, Cruise has become so indelibly linked with the Mission: Impossible franchise that it’s easy to forget what an unlikely project this actually was for him. It’s adapted from the CBS TV series that ran from 1966 to 1973. The whole point of TV’s Mission: Impossible was the team. It was an ensemble drama focused on a secret government espionage group. From the second series onward, the sleek, silver-haired Peter Graves was the star but Martin Landau, Barbara Bain, Greg Morris and Peter Lupus also had major roles. In 1993, Paramount needed to do something dramatic to hold on to Cruise. After his success in the legal thriller The Firm (1993), he was already becoming Hollywood’s most bankable star. As Variety reported at the time, studio execs began desperately “scouring their properties to find a killer, franchise-type project for Cruise”. Mission: Impossible was what they came up with as bait for their prize asset. This was a period when other stars were also appearing in movies inspired by small-screen dramas. Harrison Ford was in The Fugitive (1993) and Mel Gibson played the lead in Maverick (1994).

Cruise had watched and liked Mission: Impossible as a kid. Nonetheless, he didn’t seem a natural fit for the big screen spin-off. He was the brash, toothsome boy wonder of Hollywood, not the type to play a hard-bitten spy in a murky and cerebral drama involving clandestine US government operations in Europe.

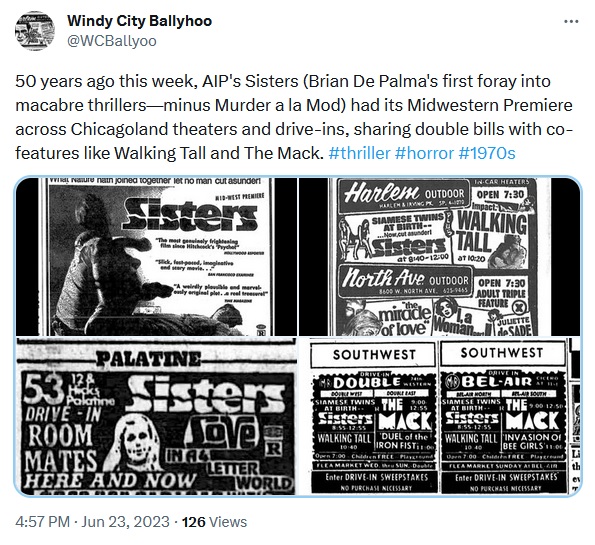

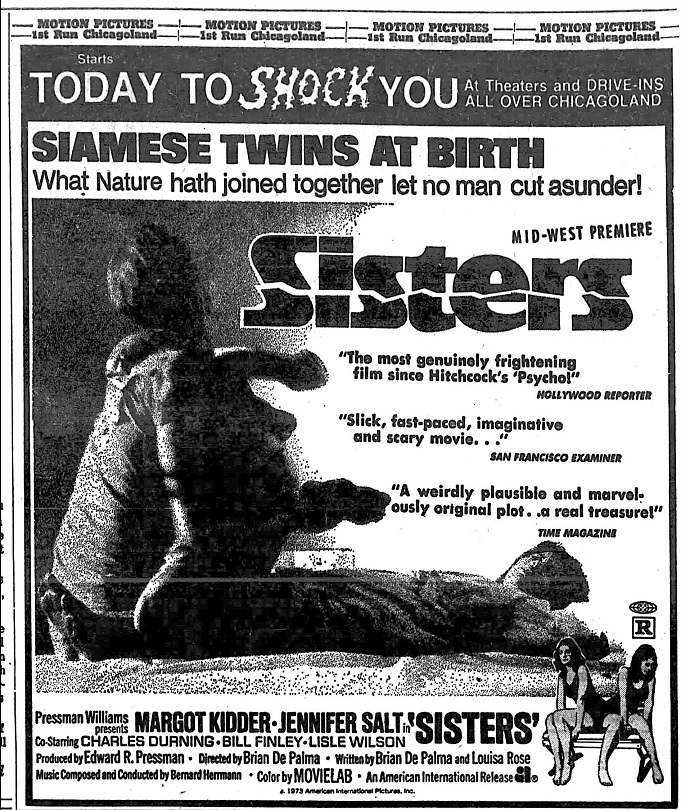

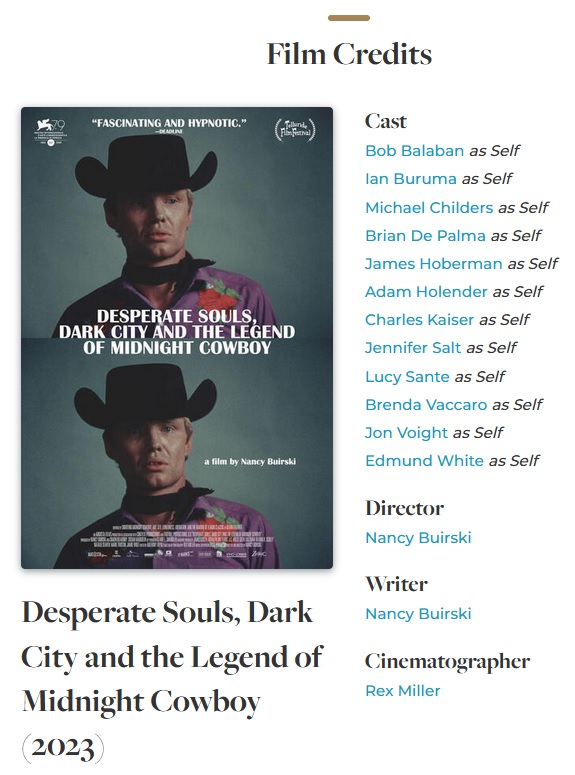

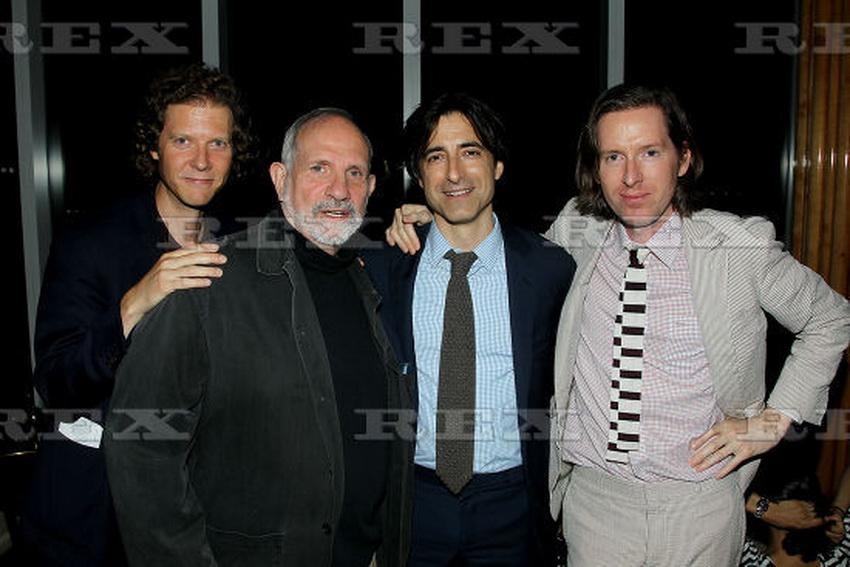

Brian De Palma was brought on board as director after Cruise met him through Spielberg. The actor went home after having dinner with the two directors and binge-watched almost all of De Palma’s films in a single sitting – and then offered him the job.

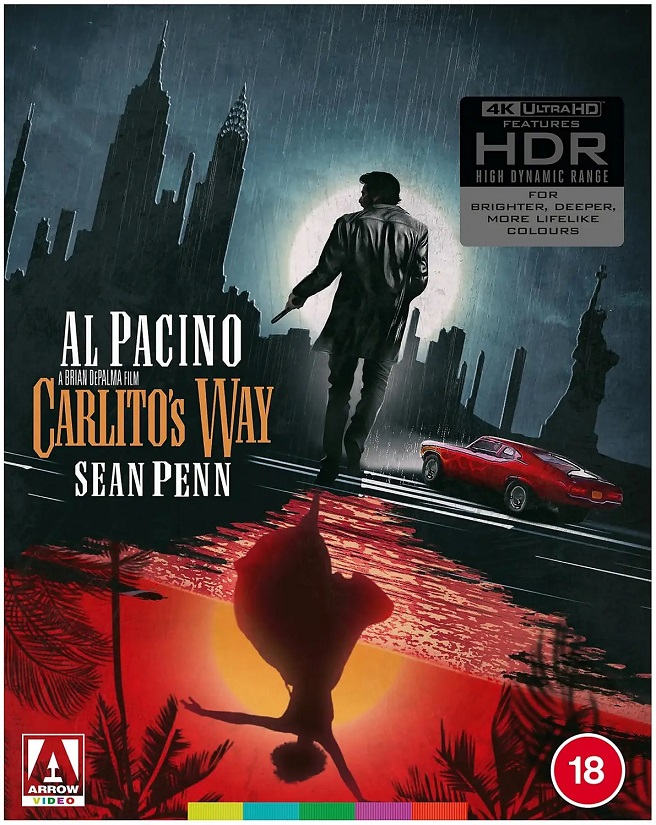

On one level, it was an astute decision. The award-winning filmmaker behind The Untouchables, (1987) Casualties of War (1989) and Carlito’s Way (1993) was a strong-willed auteur who wasn’t going to worry about upsetting the fans of the original series. The downside was that he was too big a personality simply to work as a hired hand.

There was something wanton and cruel about the way almost all the supporting actors in the Impossible Missions Force (IMF) team are dispatched so early in the movie.

“I said the first thing we have to do is kill off the whole team,” De Palma later observed of his scorched earth policy toward the other spies in the story.

Alfred Hitchcock famously had Janet Leigh stabbed to death in the shower around 45 minutes into Psycho (1960) but De Palma gets rid of Emilio Estevez, Kristin Scott Thomas and Ingeborga Dapkūnaite far more quickly. In its opening scenes, their characters all register strongly. They’re shown working together in a mission in Ukraine and then being debriefed by their boss Jim Phelps (Jon Voight) as they prepare for their next assignment in Prague. As spies go, they’re likeable, resourceful and attractive but that doesn’t stop De Palma culling them in ruthless fashion. One is impaled head-first on the spokes of a malfunctioning lift. Another is stabbed to death. They die very operatic deaths, clearing the decks so that what starts as a multi-character movie can turn into a Cruise vehicle.

Those associated with the TV series were appalled. In interviews, Graves expressed his dismay that mission leader Jim Phelps, whom he had played in staunchly heroic fashion, was now being portrayed in such a verminous light by Voight .“I am sorry they [the producers] chose to call him Phelps,” he complained, suggesting a different name would have been more appropriate. Graves appeared to think that Voight’s Phelps had nothing to do with the man he had played. An alternative reading is that after all those years working in the shadows for the US government and being paid so poorly, Phelps had simply turned rotten.

His co-star Landau was equally upset at the decision to destroy the Mission Impossible team. De Palma didn’t care. He had signed up for Mission: Impossible for one very specific reason. “I was determined to make a huge hit,” he admitted to fellow filmmakers Noah Baumbach and Jake [Paltrow] when they made their 2015 documentary about him. De Palma knew that for this to happen, Cruise had to be in as many scenes as possible.

One of the enduring fascinations of Mission: Impossible is the attrition between the star and the director. There are several accounts that claim they didn’t get on at all – although it’s unclear why they fell out. Some claimed that Cruise balked at doing the stunt in which Ethan was almost drowned after an aquarium in a restaurant explodes.

It didn’t help that the script was being reworked even as shooting was continuing. A small army of writers was involved, from David Koepp, whose credits range from Jurassic Park to Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, Steven Zaillian, then best known for Schindler’s List, and Chinatown’s Robert Towne.

In spite of the best efforts of these scribes, the plotting is very creaky. It is there simply to link the action set-pieces at the heart of the movie. There are non-sequiturs and baffling moments in which Ethan, a master of disguise, puts on or rips off masks and changes his identity. Everyone is in pursuit of a floppy disk containing the so-called NOC list of covert secret agents.

For all its contrivances, this remains a full-blooded De Palma movie, bursting with his usual directorial flourishes. From the meticulously choreographed interrogation scene that opens the movie to the continual sleights of hand and trompe l’oeil effects, slow motion explosions, scenes in which dreams and reality seem to blur and even the ruby red lipstick worn by the doomed Scott Thomas that matches the blood from her stab wound, make the film very recognisably the work of its director. Miraculously, it also succeeds as a Cruise action picture. Critics picked up on the film’s many references to Hitchcock. Sight and Sound called it “an explosion of pleasures”, comparing it to North by Northwest and praised De Palma for making the story match the relentless tempo of the famous Mission Impossible theme song by Lalo Schifrin. It was re-recorded for the film by Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen of U2.

Nor was it a case of Cruise demanding more spectacle while the highbrow director fought for a greater emphasis on character development. De Palma insisted in a 1998 interview with Premiere magazine that he was the one who fought against fierce opposition for the wonderfully overblown, Wagnerian helicopter, train and tunnel chase that ends the movie.

Mission Impossible is an exercise in pastiche but it is glorious pastiche. The bravura sequence in which Cruise’s Ethan dangles spider-style from CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, is inspired by the heist in the French thriller Rififi (1955) in which the thieves chisel through the ceiling of the apartment they’re robbing. The De Palma touch, though, is the close-up on the drop of sweat that Cruise catches in his hand, when if it hits the floor, the alarms will go off.

“One of these is enough,” an exhausted De Palma told Cruise when the actor asked him to make a sequel to Mission: Impossible. After he bowed out, John Woo, JJ Abrams, Brad Bird and Chris McQuarrie went on to direct further instalments of the franchise.

The tone of the movies has changed dramatically since 1996. The redoubtable Ving Rhames is still there as Ethan’s trusted sidekick Luther, but most of the other actors are long gone. The films have become lighter and yet more self-parodic. The stunts are as astounding as ever but what you don’t find is the sheer cinematic chutzpah that De Palma brought to the franchise. No one is comparing them to Hitchcock movies anymore.