"Perversions and Diversions"

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | May 2023 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Here's an excerpt from the interview portion:

In the new film, there’s one point where you’re talking about seeing your face on magazine covers and you say, ‘it was never a true reflection of myself.’ Is this doc, then, a true reflection of yourself?True as it could be under the circumstances. As a young man, I was pretty naïve but I always knew when I was selling a movie or enjoying the attention. This was different. When I met Davis and he told me how much my books affected him, I agreed to go on a journey with him and see where it goes. I had no agenda. I didn’t hope it would respark my film career or anything like that. I just wanted to see how a guy who thought in a similar way, and had a great track record of filmmaking, would treat this material.

How closely involved were you in Davis’s decision to construct this film in such a unique fashion?

We talked about it early on, but it’s his genre. I remember my lawyers calling me up and saying, “Here’s how it works: you’ll get three strikes to take major plot points out,” and all these other measures to defend myself against the filmmaker. But I didn’t want to do that. I just wanted to make a movie. So I waived all those provisions and I’m glad I did because god forbid I would have gone in and said don’t use my source material as part of the narrative. I thought that was so clever.

I love watching that scene where it’s talking about my relationship with [wife Tracy Pollan] and it’s footage from Bright Lights, Big City. It reminded me how lucky I’ve been in my career to work with everyone I have. Brian De Palma, Paul Schrader. It was so nice to look back and not only reflect on what was going on in my life at that point, but remember all the people I’ve met along the way.

I suppose that anybody who takes time to do this kind of exercise will find some regrets, faults in their decisions. But on the opposite end, I’m curious whether there is anything you initially felt was a mistake, a bad time in your life, that was actually much better than you initially felt, in retrospect?

I’m a goofy, optimistic guy, so all the things that have happened to me were great. I seriously wouldn’t change a thing. The difficulties I had with my early diagnosis, turning to alcohol, getting rid of that to save my marriage – as difficult and painful as all that was, I wouldn’t be the same person I am today without it, and my family wouldn’t be the same family without it. So I don’t question things, but I do celebrate them.

Some of the things in the film, people might wince at. But I was going, yeah, cool. Like that moment of me laying on the floor looking up at Tracy and finding her bored with my alcoholism and realizing that was the moment I needed to change. Yeah, I made the right decision coming out of that. The great thing about this film is the moments with my family. The way we were laughing. You can’t fake that laughter. I laugh so much it’s all you can do to get my face to not stretch beyond its skull and blow off.

Well there’s an image for a movie. Actually, it sounds pulled from The Frighteners.

Peter Jackson, I got him between masterpieces.

Hey, The Frighteners is a favourite film of mine.

I wouldn’t joke about it if I didn’t believe that, too. He’s a great filmmaker. I first met him in Toronto, when Heavenly Creatures premiered at the festival. I flew up to see it, and then agreed to make that film.

There is at one point in this doc where Davis says that you get close to the tough stuff and then dart away. How hard did he push you – and how hard did you push yourself – to get to the more difficult material?

Davis did a brilliant thing, in that he put the camera 15 feet away from where I’m sitting, back up against the wall, and he left it on. I forgot it was there. The painful stuff, when I’m looking vacant and drooling in that blank, concrete Parkinson’s stare, I couldn’t have manufactured that for him. He had the filmmaker’s instinct to know how and where to get that. I didn’t see footage until the end, so I didn’t even know what he was up to. He wasn’t going to do talking heads – the one talking head was just mine, even though my head can barely talk some time. If I had any prenegotiated control over the material, it would have been a disaster.

I would, though, like to see a sequel where it’s just talking heads of collaborators you’ve worked with.

They gave me an Academy Award this year for my humanitarian work, which was great because Woody Harrelson presented it. He gets up and starts telling these stories and I thought, oh Jesus. Someone once said to me that we were “eighties famous,” and that’s true. We had a different perspective. There were none of these things [points to his smartphone]. It was just hardcore.

Woody starts to tell this story about when we were in Thailand, and I took them through the jungle. It was me, Woody and [hockey player] Cam Neely, and we found this little hut. It was Deliverance in Southeast Asia. This kid comes out who I had met before, and I gave him this big bag of baht, and he took me to this concrete wall and we jumped over. That’s when Woody and Cam realized there were like 35 cobras in there. I just sat there until they picked up a cobra. Its blood was drained and mixed with Thai whiskey and we drank it. “Brotherhood of the snake,” or something goofy like that. Madness. If we got a whole group of my friends and told these stories, we’d never get out of there.

I think you just found the title of your next doc, though. Michael J. Fox: Brotherhood of the Snake.

Or Fox Eats Snake.

In an interview with GQ, Leguizamo revealed that he was so sick of auditioning to play drug dealers early in his career that he considered passing on his now-iconic role as Benny Blanco in Brian De Palma’s “Carlito’s Way.”“I’m a Latin guy and I didn’t wanna play another drug dealer. I was just kind of sick of that kind of routine,” Leguizamo said. “So I turned it down three times.”

He continued to resist the role, only to learn that one of Hollywood’s other rising Hispanic stars, Benicio Del Toro, was also in the mix for it. Once he learned Del Toro was interested, Leguizamo said that he opted to do the film after realizing it was a good career move.

“The producers said, ‘Look, this is the last time I’m coming to you. We’re gonna go to Benicio,'” he said. “Okay, I’ll take it!”

Leguizamo’s thoughts about not wanting to play drug dealers echo similar comments he made in a recent interview with IndieWire. The actor explained that the limited range of roles he was considered for as a young actor shaped his view about the importance of representation in films.

As we’ve discussed in previous entries, Erotic Thrillers owe a great deal to Film Noir, which – thanks to the Hays Code – tended to end by reinforcing a morally black and white view of the world. Body Double refuses this script: not only does Holly disapprove of being forced into Jake’s crusade and nearly being buried alive, but the pair don’t wind up together. And while the end of the film confirms that Jake has overcome his claustrophobia and returned to work, the final scene plays like it is gently mocking Jake’s B-movie role as a pervy vampire who is still working with body doubles.In this way, Body Double works both as a great Erotic Thriller, and as self-aware meta commentary by De Palma about the subgenre and his own reputation within it. That’s pretty clever.

According to the catalog of the American Film Institute, Sisters carries a copyright date of April 18, 1973. This is when it landed in theaters in Los Angeles, although, moving throughout the U.S., it would not reach New York theaters until October of 1973. That month, De Palma was interviewed by The New York Times' Charles Higham:

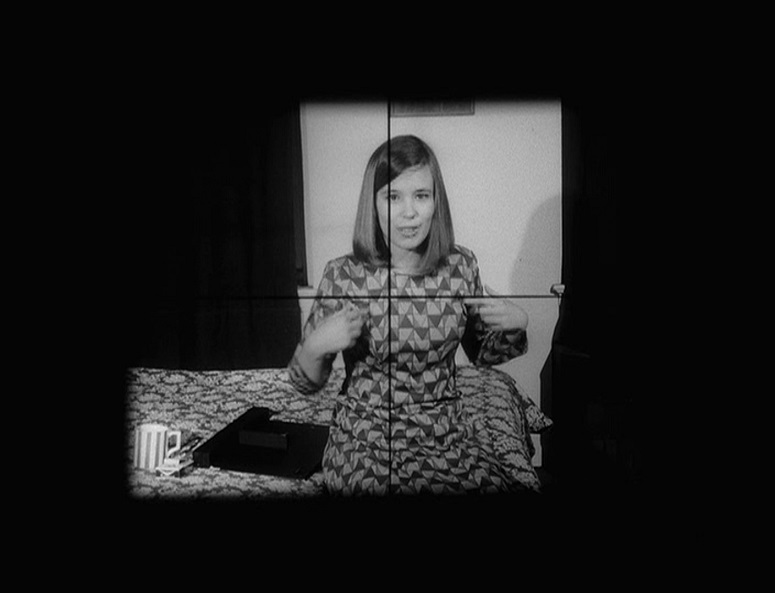

De Palma gets up, coldly answers a persistent telephone caller, and then sinks back in his chair, looking tired and puffy. “I'm much happier with ‘Sisters.’ That is mine from beginning to end. American International took on the distribution — but they didn't tamper with it at all. It was shot on location on Staten Island, I liked the idea of a very suburban setting for a horror story about a small‐town girl reporter who sees a murder from her apartment window.”Not all of “Sisters” was shot on Staten Island, however. “We built the set of the apartment where the murder takes place on East 4th Street, right next to the Cafe La Mama. I loved the voyeuristic mood of the story —here is this girl, this amateur sleuth, who gazes through windows and sees a man murdered and all kinds of horrifying things going on. Things half‐seen. Like most directors, I'm a voyeur at heart. I loved dragging the audience through the whole psychodrama of an insane situation. The audience becomes this girl, peering through a psychological hole. Since, in a way, I am the girl, the people out there can be her, too.”

De Palma’s incredible one-take intro to Santoro and his sleazy existence shows us arounds corridors, up and down escalators down to ringside. It’s dialog-heavy, incredibly complicated in its staging and so exciting to watch.One of Santoro’s best friends, Commander Kevin Dunne (Gary Sinise) sits alongside him on ringside seats. When a shot rings out and a powerful figure sitting near Santoro is now dead, the event erupts into anarchy.

Santoro and Dunne immediately sweep the area and round up the suspects. Who took the shot, why did they do it and is there one person responsible for the public assassination? How do you solve a murder that takes place in plain sight with “14,000 eyewitnesses?”

Because it’s De Palma, the expected Hitchcock visuals and themes are present. However, even with those aspects in place, there are more neo-noir themes on hand, as well as De Palma doing Robert Altman taking on “Rashomon.”

There’s a McGuffin about Air Guard Missile Tests but the core of the film is Santoro’s belatedly finding a moral center in a corrupt world.

De Palma is once again exploring media manipulation and distraction through large-scale diversion. It could be interpreted as political satire as just flat out American social commentary.

De Palma is dipping his toe into the “Blow Out” (1981) pool once more. “Snake Eyes” is a smaller film than De Palma’s anti-commercial, challenging tour de force of the original “Mission: Impossible” (1996) but still made with a bravado showmanship to match the work of his leading man.

“Snake Eyes” isn’t an action movie but a thrillingly staged mystery, which made it an odd attraction during the summer of 1998. Coming off of his back-to-back blockbusters of “Con Air” and “Face/Off” and the surprise hit of “City of Angels” earlier in the year, Cage was on a roll that lasted for years.

Playing Santoro, Cage is on fire from his first entrance. The character simmers down as the discoveries of the investigation become increasingly grave. Cage is not being over the top but playing a brash, inhibition-free jerk whose lack of a moral center changes drastically in a single evening.

There is no convincing naysayers who loathe any period of Cage’s work, whether it’s his early post-“Peggy Sue” choices, his commercial breakthrough after winning the Oscar, or the on-again-off-again era of wild creative peaks and valleys he’s currently in.

Cage always takes big swings and is rarely (if ever) accused of being subtle.

Nevertheless, the actor’s willingness to give nearly every project he takes on an above and beyond approach, giving it his all when the movie itself may not need or deserve it, has made him one of my favorites.

Alongside his incredible turn in Werner Herzog’s off-the-wall “Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans” (2009), this is my favorite of his “big” performances.

In both cases, the initial bravado of the characters masks the moral rot beneath, as both characters find a form of redemption but, in the end, haven’t entirely reformed their wicked ways.

The shot of a bloodied bill and the final, painful look Santoro gives it, says everything about the character and how far he’s come. It’s the film’s most important shot and solidifies the film’s neo-noir identity.