'AMERICAN STUDIO MOVIES DON'T END LIKE THAT'

FILM WRITER TRAVIS CRAWFORD, WHO PASSED AWAY THIS WEEK, WROTE ABOUT 'BLOW OUT' IN 2011

According to

Scott Macaulay at Filmmaker Magazine, "Film writer and festival curator

Travis Crawford, who worked extensively with various home video labels in the restoration of classic foreign-language, independent and genre work, died this week, I was saddened to learn via social media. He was 52."

"Crawford," Macaulay continues, "who for many years curated the Philadelphia Film Festival’s Danger after Dark series, wrote extensively for Filmmaker over the years, predominantly in the late aughts and early ’10s, when he headed up the print magazine’s 'Load and Play' columns." Macaulay provides a link to one of those columns, from 2011, in which Crawford writes about the then-recently-released Criterion edition of Blow Out:

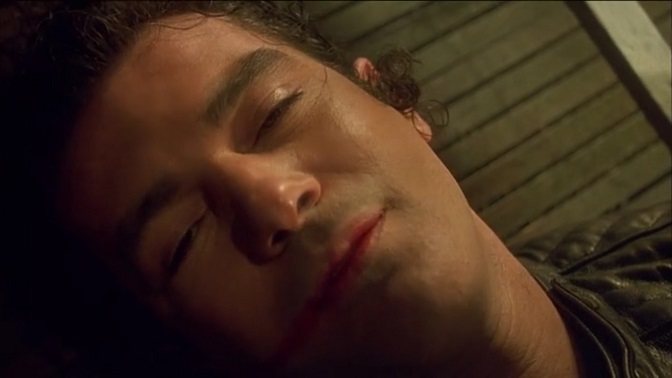

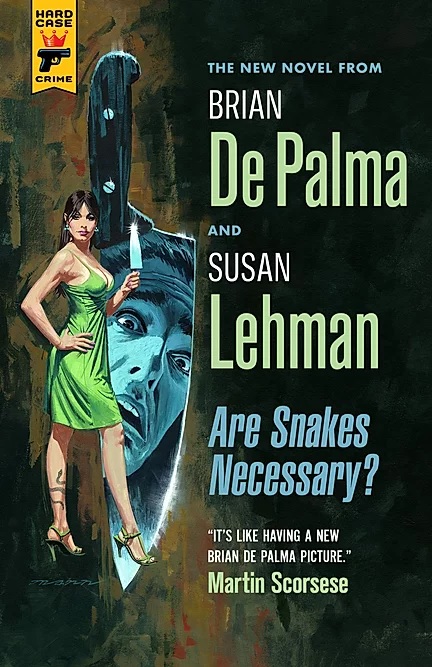

The ending of Brian De Palma’s Blow Out hits you in the chest like a hammer. It’s not supposed to be this way; American studio movies don’t end like that. But of course it’s the heartbreaking denouement that has partially helped to make the film endure in the 30 intervening years since its commercially disastrous release, though one can certainly fathom how it alienated audiences at the time (for the record, some critics were passionate defenders; it’s just that most viewers don’t savor being implicated in the spectacle of violence as it is quickly transformed into tragedy). As De Palma himself has wryly observed, the studio likely just expected another erotic romp like Dressed to Kill (De Palma’s previous surprise hit for the Filmways outfit) and were unprepared for a downbeat but cinematically exhilarating last gasp of bravura filmmaking, political critique, and social cynicism that made its ’70s predecessors like The Conversation and The Parallax View seem like Oliver! by contrast. But as the greatest film ever made by one of the two or three most important filmmakers to emerge from the “New Hollywood” movement of the ’60s and ’70s, Blow Out is among the most significant films of the past three decades, and the film has been thankfully reappraised in subsequent years. Hopefully its new Criterion Collection Blu-ray and DVD special-edition release will also help to introduce it to a younger generation of film enthusiasts. Of course, during the ’70s (clearly, a loosely defined era in American filmmaking), challenging audience expectations — whether socio-political or purely filmic — had become rather expected, so perhaps De Palma (much like his old friend Scorsese who artistically triumphed with the similarly commercially underappreciated Raging Bull the previous year — trivia note: it was actually De Palma who first introduced Scorsese to De Niro at a party) was unaware of the post-Jaws/Star Wars shift in the new Reagan-era American cinema. But De Palma had just come off a hit with Dressed to Kill, and had also enjoyed a pop culture phenomenon with Carrie only a few years earlier; even his less financially successful genre endeavors like Obsession, Phantom of the Paradise, and Sisters hardly seemed to exist in the same unapologetically confrontational realm as some of Scorsese’s more overtly personal work. So for De Palma to embark on a violent suspense exercise — one with stars like John Travolta and De Palma’s then-wife Nancy Allen in addition — may have seemed like a relatively safe commercial bet…no matter than the film harked back to the grim and anti-authoritarian conspiracy thrillers of the decade that preceded Blow Out’s release. But for those who mistakenly believed that De Palma’s career essentially began with Sisters, the political pessimism of Blow Out might seem like an unexpected departure indeed — yet, Sisters was actually the filmmaker’s seventh feature film, and if anything, Blow Out serves as a newfound and masterful fusion of the director’s Hitchcockian tales of mayhem and perversion, with a radical political consciousness seemingly jettisoned eight years prior.

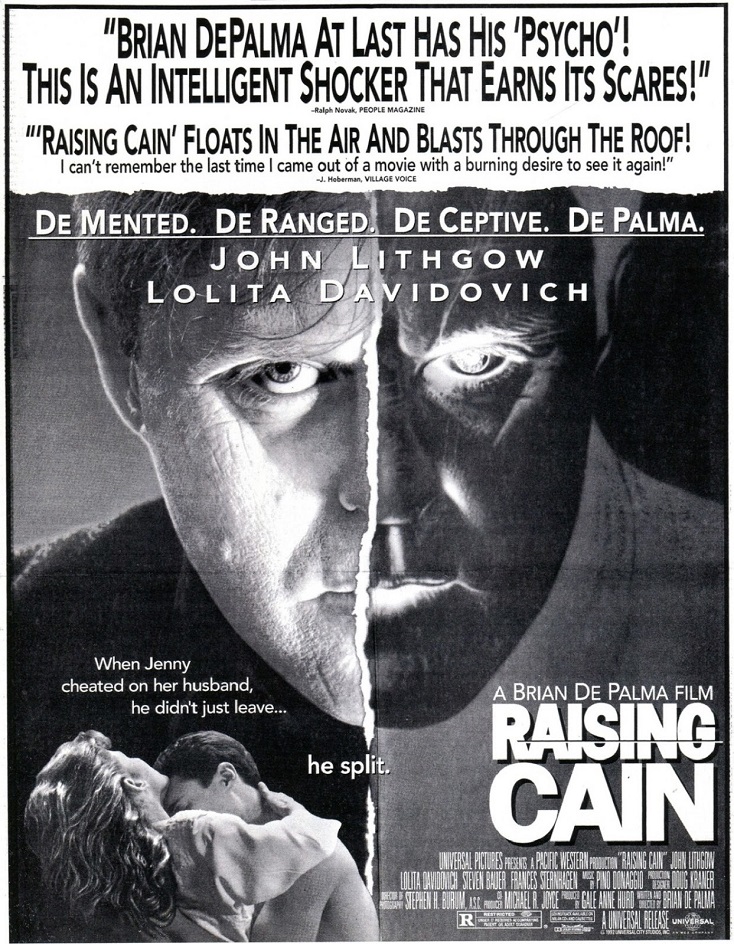

De Palma’s first six features — Murder a la Mod (included in its entirety as a supplementary feature on this Criterion disc), Greetings, The Wedding Party, Dionysus, Hi, Mom!, and Get to Know Your Rabbit — demonstrate political concerns and counterculture beliefs that would only scarcely return in his later work, sometimes with rewarding results (the underrated Casualties of War) but sometimes with ill-advised ramifications (the misguided Redacted). If De Palma discarded a playful political sensibility in favor of equally playful approaches to film technique beginning with Sisters in ‘73, Blow Out is incredibly rewarding in the way that it combines both sensibilities. Yet it would be disingenuous to imply that this is the principal factor for the movie’s enormous impact: if De Palma’s subsequent thrillers found him experimenting with form and style to the point of gleeful and unabashed self-parody (most notably in the often hilarious likes of Body Double, Femme Fatale, and — most obviously — Raising Cain), Blow Out is played comparatively “straight,” but with no less contagious joy for the medium of filmmaking. And the political backdrop provides additional narrative gravity to a story that is, above all else, a genuinely melancholy and heartfelt tale of doomed love and shattered political idealism.