FEMME FATALE & RAISING CAIN

Updated: Monday, August 8, 2022 11:02 PM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | August 2022 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

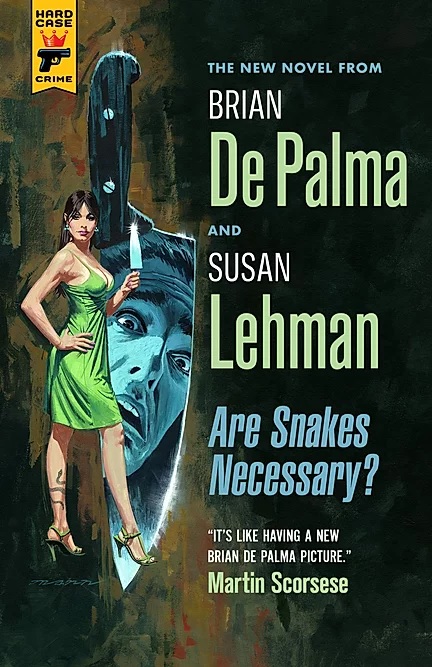

Along with Herzog's novel The Twilight World, the article mentions Michael Mann's Heat 2, David Koepp's Aurora and Cold Storage, Quentin Tarantino's novelization of his own film, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood, and, of course, Are Snakes Necessary? which was written by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman. Here's a brief excerpt from Zenou's article:

But what may appeal most to filmmakers is the autonomy that comes with writing. Charles Ardai, De Palma’s publisher at Hard Case Crime, thinks this ultimately explains why so many filmmakers turn to novels: “It’s enormously appealing to a director or screenwriter to generate a piece of art solitaire. This is a way to go from being one of an ensemble, even the most important one, to being a soloist.” Koepp concurs, adding “everybody on a movie is an assistant storyteller”. A novel is “more fulfilling because it’s more yours”, he says, “there are no other opinions to consider”.And then there is the absence of budgets and shooting schedules. Herzog, in typically vivid style, likens the filming process to “open-heart surgery”, which must be completed “under limited time conditions”. While publishers can be stalled, film shoots, like operations, are ruthlessly unforgiving. “You cannot do open-heart surgeries stretching out over two weeks,” Herzog says. “You have to do it in half a day, otherwise the patient is going to be dead.”

Prior to her career as an actress, Mary Alice was a teacher in Chicago. In 1967, she moved to New York, taking parts in theater, film, and television. In 1974, she starred in the PBS movie The Sty of the Blind Pig. In the 1976 film Sparkle, which was inspired by Diana Ross and the Supremes, she played Effie Williams, "the single mom raising daughters played by Irene Cara, Lonette McKee and Dwan Smith," as Mike Barnes puts it in The Hollywood Reporter. Mary Alice appeared in episodes of various TV series throughout the years, and in 1977, she acted opposite Morgan Freeman in Cockfight at the American Place Theater in New York. According to theNew York Post obituary by Erin Keller, Mary Alice "played Bostic, a dorm director, in the Cosby Show spinoff for two seasons in the 1980s. In those years, she also portrayed Ellie Grant Hubbard in All My Children. Her performance as Rose in the 1987 production of August Wilson’s Fences earned her a Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play. In 1992, she won the Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series for I’ll Fly Away."

Three years after winning the aforementioned Tony Award, Mary Alice portrayed the key role of Annie Lamb, the mother of the boy injured in the hit-and-run accident that lay at the center of The Bonfire Of The Vanities. That same year, according to The Hollywood Reporter obituary by Mike Barnes, "Alice played Nurse Margaret opposite Robin Williams and Robert De Niro in Awakenings, directed by Penny Marshall", and also "the family matriarch dealing with a disruptive guest (Danny Glover) in Charles Burnett’s To Sleep With Anger."

"Crawford," Macaulay continues, "who for many years curated the Philadelphia Film Festival’s Danger after Dark series, wrote extensively for Filmmaker over the years, predominantly in the late aughts and early ’10s, when he headed up the print magazine’s 'Load and Play' columns." Macaulay provides a link to one of those columns, from 2011, in which Crawford writes about the then-recently-released Criterion edition of Blow Out:

The ending of Brian De Palma’s Blow Out hits you in the chest like a hammer. It’s not supposed to be this way; American studio movies don’t end like that. But of course it’s the heartbreaking denouement that has partially helped to make the film endure in the 30 intervening years since its commercially disastrous release, though one can certainly fathom how it alienated audiences at the time (for the record, some critics were passionate defenders; it’s just that most viewers don’t savor being implicated in the spectacle of violence as it is quickly transformed into tragedy). As De Palma himself has wryly observed, the studio likely just expected another erotic romp like Dressed to Kill (De Palma’s previous surprise hit for the Filmways outfit) and were unprepared for a downbeat but cinematically exhilarating last gasp of bravura filmmaking, political critique, and social cynicism that made its ’70s predecessors like The Conversation and The Parallax View seem like Oliver! by contrast. But as the greatest film ever made by one of the two or three most important filmmakers to emerge from the “New Hollywood” movement of the ’60s and ’70s, Blow Out is among the most significant films of the past three decades, and the film has been thankfully reappraised in subsequent years. Hopefully its new Criterion Collection Blu-ray and DVD special-edition release will also help to introduce it to a younger generation of film enthusiasts.Of course, during the ’70s (clearly, a loosely defined era in American filmmaking), challenging audience expectations — whether socio-political or purely filmic — had become rather expected, so perhaps De Palma (much like his old friend Scorsese who artistically triumphed with the similarly commercially underappreciated Raging Bull the previous year — trivia note: it was actually De Palma who first introduced Scorsese to De Niro at a party) was unaware of the post-Jaws/Star Wars shift in the new Reagan-era American cinema. But De Palma had just come off a hit with Dressed to Kill, and had also enjoyed a pop culture phenomenon with Carrie only a few years earlier; even his less financially successful genre endeavors like Obsession, Phantom of the Paradise, and Sisters hardly seemed to exist in the same unapologetically confrontational realm as some of Scorsese’s more overtly personal work. So for De Palma to embark on a violent suspense exercise — one with stars like John Travolta and De Palma’s then-wife Nancy Allen in addition — may have seemed like a relatively safe commercial bet…no matter than the film harked back to the grim and anti-authoritarian conspiracy thrillers of the decade that preceded Blow Out’s release. But for those who mistakenly believed that De Palma’s career essentially began with Sisters, the political pessimism of Blow Out might seem like an unexpected departure indeed — yet, Sisters was actually the filmmaker’s seventh feature film, and if anything, Blow Out serves as a newfound and masterful fusion of the director’s Hitchcockian tales of mayhem and perversion, with a radical political consciousness seemingly jettisoned eight years prior.

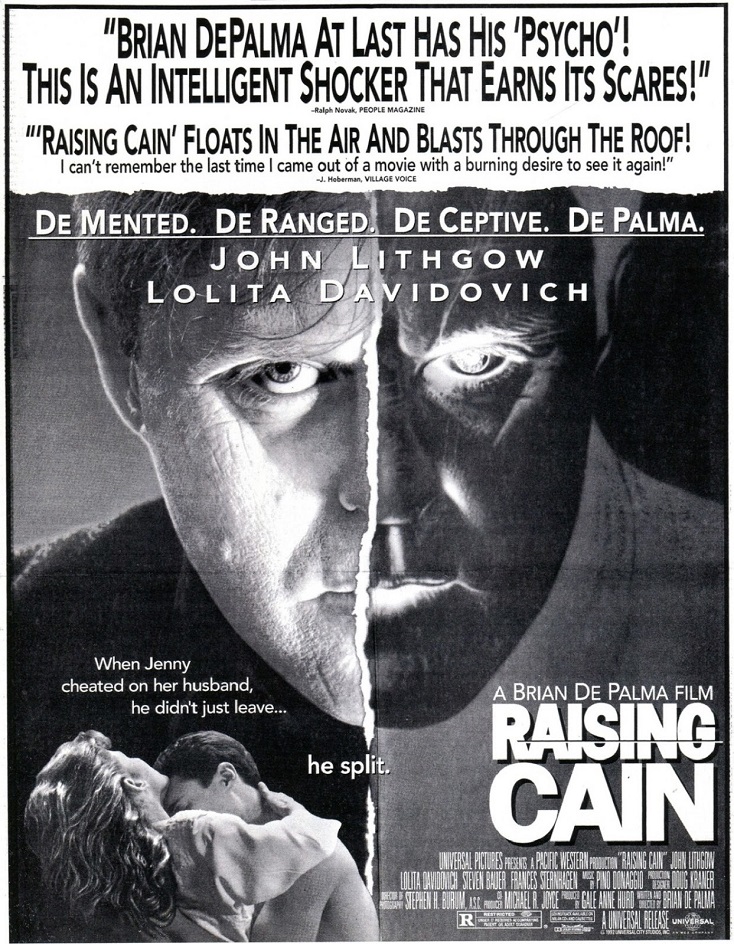

De Palma’s first six features — Murder a la Mod (included in its entirety as a supplementary feature on this Criterion disc), Greetings, The Wedding Party, Dionysus, Hi, Mom!, and Get to Know Your Rabbit — demonstrate political concerns and counterculture beliefs that would only scarcely return in his later work, sometimes with rewarding results (the underrated Casualties of War) but sometimes with ill-advised ramifications (the misguided Redacted). If De Palma discarded a playful political sensibility in favor of equally playful approaches to film technique beginning with Sisters in ‘73, Blow Out is incredibly rewarding in the way that it combines both sensibilities. Yet it would be disingenuous to imply that this is the principal factor for the movie’s enormous impact: if De Palma’s subsequent thrillers found him experimenting with form and style to the point of gleeful and unabashed self-parody (most notably in the often hilarious likes of Body Double, Femme Fatale, and — most obviously — Raising Cain), Blow Out is played comparatively “straight,” but with no less contagious joy for the medium of filmmaking. And the political backdrop provides additional narrative gravity to a story that is, above all else, a genuinely melancholy and heartfelt tale of doomed love and shattered political idealism.

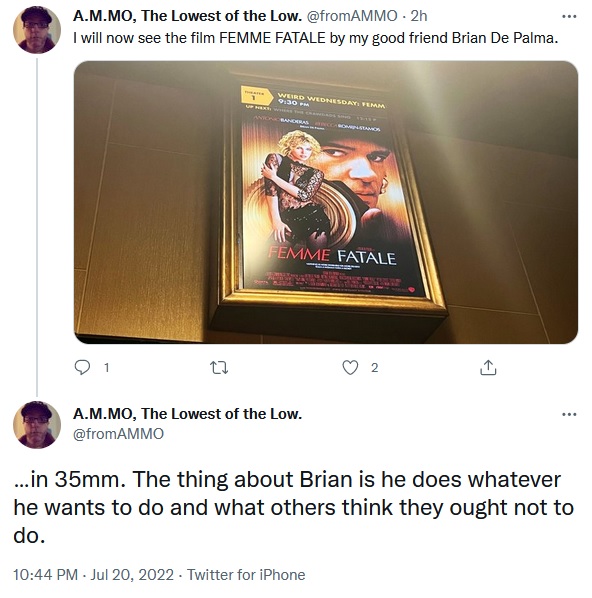

An ode to classic film noir, FEMME FATALE opens with one of De Palma's greatest set pieces: a stealthy jewel heist by a gang led by seductive thief Laure (Rebecca Romijn) that takes place during a gala screening at the Cannes Film Festival. After double-crossing her partners, Laure flees to the Paris suburbs, where a whirlwind of unlikely events results in her assuming the identity of her doppelgänger, marrying a wealthy American diplomat (Peter Coyote), and assuming a new life in the US. Returning to Paris seven years later when her husband is made the American ambassador to France, Laure is targeted by her former accomplices, and she ropes in a bewildered Spanish photographer (a convincingly confused Antonio Banderas) for a deadly game of double-, triple- and quadruple-crosses.

In the main title, the melody of Tony’s theme kicks in with an up-tempo disco beat over footage of Cubans arriving by boat (an interesting juxtaposition to the dejected faces of real refugees). This was the only sequence the editors were able to cut to, but only because De Palma’s original vision was jettisoned at the last minute. “There was a title sequence crisis,” says Ray. “Brian had in his head that the title sequence should be a series of newsreel clips, which would eventually freeze, go to high contrast black-and-white, and the white parts would morph into mounds of cocaine, which would blow away and reveal the text of the title. And that was a huge thing to do. I think he had it in his mind you could shoot that live, and we did tests, and they were terrible. I think the only way to do this convincingly would be to animate it, which was a big deal.” Instead, Greenberg suggested just intercutting the film’s title cards with the existing newsreel footage, which Ray hastily did as the clock was ticking. “The music was already locked, so the length was locked in. But that was the only time that we had music.”

Within the first few minutes, host Al Horner asks Koepp about his approach to character. "I would love to be one of those writers I hear, on shows very much like this, who say, 'It all begins with character," Koepp replies. "It must begin with character.' I'm just not. And I'm not sure I believe them. I think you have an idea about something. You don't... well, maybe you do, I don't know. I think, I have an idea. And then I think, I do exactly as you said, I think, 'Who is either the best or the worst person possible for this to happen to.' In the case of KIMI, I thought, who is the worst possible person for this to happen to. The idea was, you know, that we overhear... there are people whose job it is to listen to all those little recordings that Siri and Alexa make in our homes, and to flag irregularities and try to correct the algorithm for where it misinterpreted things. And I read an article that talked about the people who listen to those. And I thought, ooh, that's interesting. I like that person. And what if they heard something terrible. Then I thought, who's the worst person that could happen to, and it would be someone who doesn't like to leave their house. That's why they have this job, and they must go out in order to effect change in the world. So, in that case, it was the worst. In Mission: Impossible, that kind of spy thing, you want to think, who is the best person for this to happen to. And that of course is the indestructible Tom Cruise."

CBR's Leon Miller posted an article three days ago with quotes of Koepp, from the podcast, about why they decided to kill off the first team in the film:

Mission: Impossible co-writer David Koepp recently explained why Ethan Hunt's first team had to die in the 1996 espionage blockbuster.Koepp revealed that director Brian De Palma decided to kill off the original Impossible Missions Force line-up to keep the movie's focus on Tom Cruise as Hunt, in an episode of Script Apart. "There's a fundamental flaw in Mission: Impossible as a movie with Tom Cruise, as a concept," he said, "It's an idea that should not work. It appears it has [laughs], but it is essentially an ensemble, that is its very nature. It's a team movie if it's based on the [original 1960s Mission: Impossible] television show."

"So, for this ensemble movie, the one piece of casting is the biggest movie star in the world with an incredibly dominant personality," Koepp continued. "So, it's just not going to work, so Brian's idea was 'We have to kill everybody.' And it's a good point. That's his approach on a number of films, but in this one in particular, it really worked. He's like 'Look, it's an ensemble, so we have to start it like an ensemble, kill everybody, so we've only got one left, and he's the star, and let him put together another team. But we'll always orient it around him,' which was a brilliant idea."

"Brian [De Palma] had shown an early cut of the movie to some filmmaker friends. And George Lucas saw it and said, 'You're missing the spaghetti scene.' ... Brian said, 'What's the spaghetti scene?' And he said, 'You know, where they all sit around and eat spaghetti and they get the mission. You don't know who these people are. You start in the middle of a mission.' Brian said, 'Well, it's exciting to start in the middle of a mission.' And George said, 'It's not exciting unless you know who they are.'"