PETER TONGUETTE ON NICOLAS CAGE'S "UNINHIBITED ACTING CHOICES" IN 'SNAKE EYES' & BEYOND

Reviewing The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent side-by-side with Keith Phipps' book Age of Cage: Four Decades of Hollywood Through One Singular Career, Washington Examiner's Peter Tonguette highlights Cage's work in Snake Eyes:

What qualifies as a great performance? Decades of conditioning by movie critics, not to mention Oscar voters who insist on recognizing Meryl Streep each time she adopts a new accent, have led many moviegoers to think they must applaud when an actor is said to “disappear” into a part. Such performers are thought to be paragons of selflessness and subtlety, willing to set aside their own personalities for the sake of high art.In truth, moviegoers have always taken pleasure in performers who remain blatantly and unapologetically themselves on the big screen — those who seem less interested in incarnating a character than simply summoning their own reserves of charisma, intelligence, and even eccentricity. During his long reign as America’s most widely admired actor, Marlon Brando became so flagrant in his tics, mannerisms, and improvised riffs that it was impossible for an audience to suspend disbelief and accept him as an actual character. In his brilliant late-career turn in the Mafia comedy The Freshman (1990), Brando managed to render the plot, and sometimes even the jokes themselves, irrelevant thanks to his torrent of self-referential mumbling and random bits of business — say, the long, drawn-out way he deposits sugar into Matthew Broderick’s cup of espresso. This is less performing than performance art.

For audiences to enjoy this sort of thing, however, an actor has to be willing to hover above the material: to kid it or act around it or simply ignore it. Such is the secret to the success of Samuel L. Jackson, whose signature rhetorical device, over-the-top screaming, arguably contributed immeasurably to the success of Quentin Tarantino’s early films. (Try to imagine anyone but Jackson saying, in Pulp Fiction, “Do they speak English in What?”) And it formed the basis for at least one entire movie, the regrettable (but not unentertaining!) 2006 fright film Snakes on a Plane.

Yet the undisputed master of molding movies to his persona is surely Nicolas Cage, who, long before becoming something of a punchline for his gleefully unrestrained performances in a series of increasingly odd, random, and ill-funded productions, seemed to delight in disrupting otherwise ordinary movies with his jittery, hyped up, always-on-edge performance style.

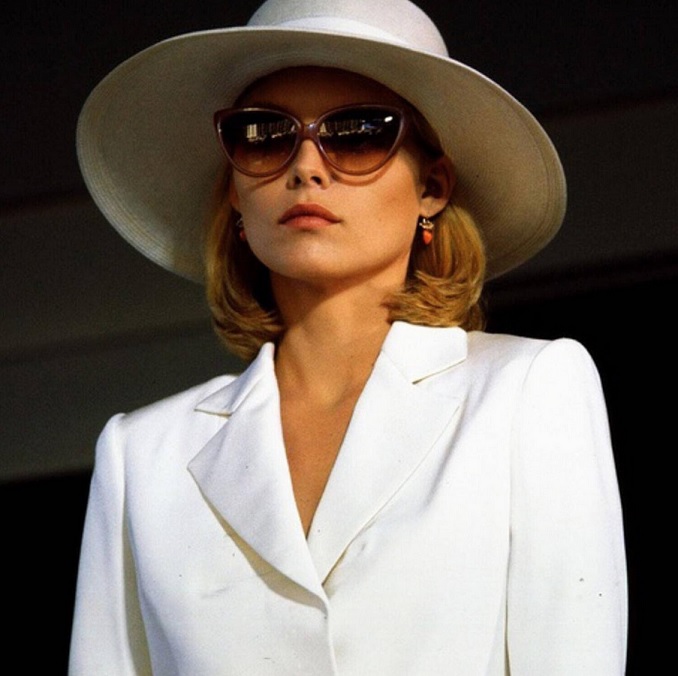

I remember the first time I became conscious that Cage was no longer putting his gifts at the service of mere characterization — if he ever was. In 1998, just three years after he gave an Oscar-winning performance in Mike Figgis’s Leaving Las Vegas, Cage headlined Brian De Palma’s Atlantic City-set morality tale Snake Eyes. Playing proudly corruptible detective Rick Santoro, Cage looks to have remembered and recycled every actor who ever played a small-time wheeler-dealer in a movie, placed them all in a blender, and come out with a rich, thick puree of smooth talk, hustle, and con. His performance is loud, wild-eyed, and delightfully vulgar: as garish as the Hawaiian shirt he wears and as hyperactive as director De Palma’s roving Steadicam. At the time, Cage’s uninhibited acting choices did not seem so strange. Those of us who had grown up with the actor — he had already made the Coen brothers’ Raising Arizona (1987), David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990), Michael Bay’s The Rock (1996) — were more or less getting what we wanted: pure, unvarnished Cage.

But as H.L. Mencken said of what democracy delivers to the people, we who cheered on Cage’s scenery-chewing got what we deserved, and we got it good and hard. As his projects became more obviously questionable and less auteur-driven — for example, his appearance in the gooey holiday comedy The Family Man (2000) or the preposterous World War II romance Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (2001) — Cage’s accumulated weirdness stood out more and more. I concede that there’s something deeply unfair in this analysis: Cage was the same unruly, unpredictable, unrealistic actor when he was appearing in respectable art house releases as when he was showing up in schlock on the order of Ghost Rider (2007) and the National Treasure series. Cage didn’t change as much as our tolerance for him did — a tolerance lowered, undoubtedly, due to the almost unfathomable increase in his output starting in the early 2010s, which coincided with, or resulted from, a period of financial difficulty.

Updated: Friday, April 29, 2022 12:10 AM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post