REVISITING JANET MASLIN'S NY TIMES REVIEW OF 'RAISING CAIN'

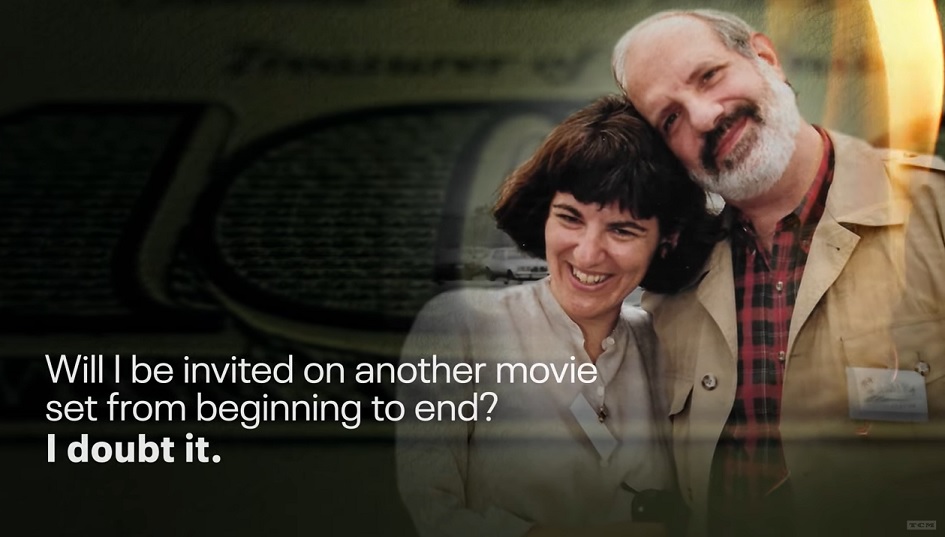

Thanks to a tweet from Metacritic for highlighting Janet Maslin's glowing 1992 review of Brian De Palma's Raising Cain, from The New York Times. With all due respect to the wonderful things Peet Gelderblom has accomplished, Maslin's review is a reminder that the true "director's cut" of Raising Cain was released in theaters in 1992:

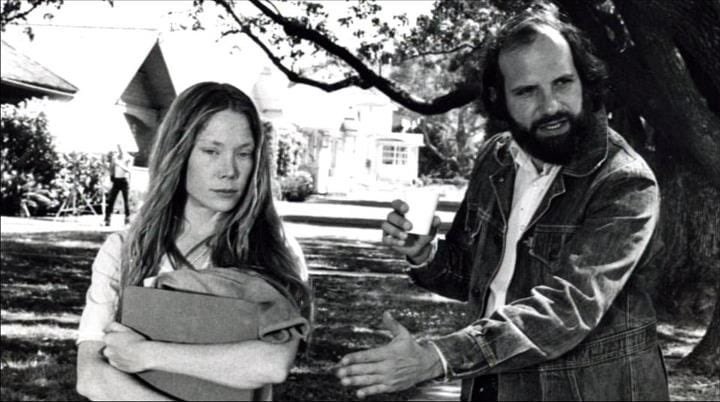

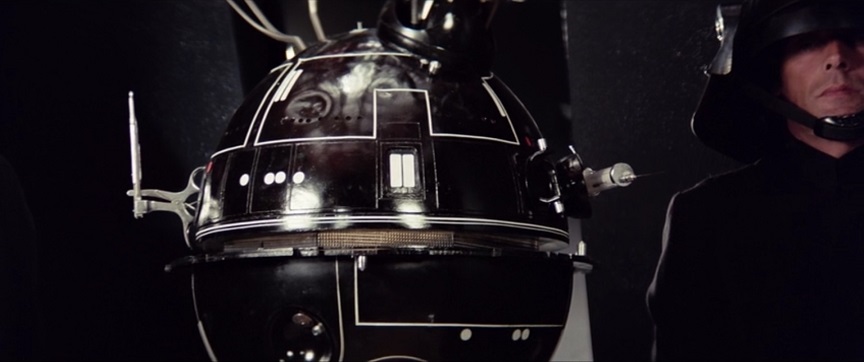

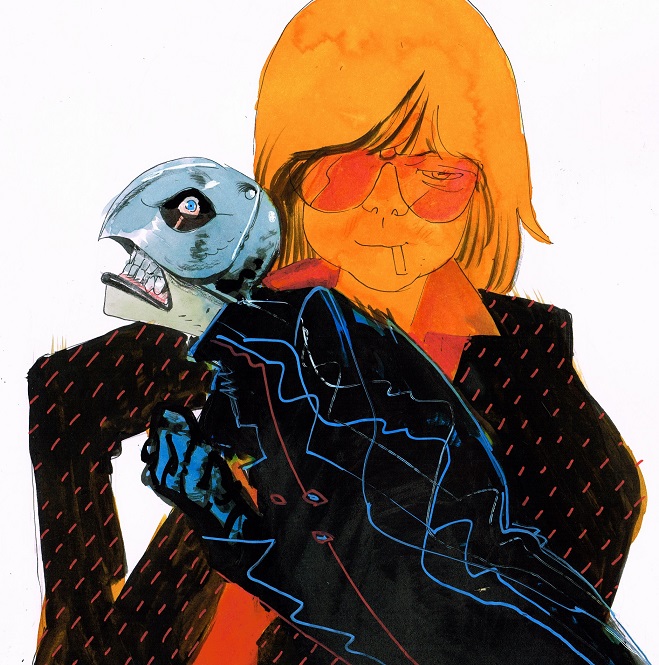

A peaceful playground. A pleasant day. And two parents making small talk as they watch their children and then share a ride home. Dr. Carter Nix (John Lithgow), a child psychiatrist taking time off from his work to help bring up his daughter, engages a female friend in small talk about the legitimacy of conducting psychological studies on small children. The conversation starts innocently, but within moments -- during the course of an edgy, sustained driving shot executed with bravura ease -- it turns hostile enough to make Carter sneeze. Even worse, it makes Carter commit murder.Bounding back gamely from "The Bonfire of the Vanities," Brian De Palma has vigorously returned to familiar ground. "Raising Cain," a delirious thriller starring John Lithgow as a man with at least three more personalities than he really needs, finds Mr. De Palma creating spellbinding, beautifully executed images that often make practically no sense. Working with an exhilarating sense of freedom, he seems to care not in the least what any of it really means. The results are playful, lively and no less unstrung than Dr. Carter Nix himself.

In his early days, Mr. De Palma sometimes labored to make his neo-Hitchcockian thrillers appear reasonable. This time that kind of strain is gone. So is the need to compare Mr. De Palma's latest psychological mystery, which he both wrote and directed, with any films other than his own. Less grisly and more mischievous than "Body Double," infused with the kind of free-floating menace that colored "The Fury," "Raising Cain" is best watched as a series of overlapping scenarios that may or may not be taking place in the real world. By the time it reaches its greatest feverishness, the film has featured a tussle involving three characters. One is real, one probably imaginary and one may actually be dead. At that point, it's hard to know for sure.

The Cain to whom the title refers is Carter's vicious alter ego, who likes to appear whenever a violent crime is in the wind. (This time, Mr. De Palma dispenses with the power drills and keeps the violence implicit and off screen.) Frequently shooting Cain from disturbing, tilted angles, Mr. De Palma may be promising to provide some kind of stylistic compass, but the film is often too caught up in its own craziness to keep track of that. Risky as it sounds, "Raising Cain" is enjoyable precisely because it makes the most of its own lunacy and stays so far out on a limb.

The fact that "Raising Cain" is beautifully made is, of course, another attraction. The film offers no warning as to when Mr. De Palma will launch into a spectacular tracking shot (a stunning one involving Frances Sternhagen goes on for about five minutes) or spin out a multi-tiered, slow-motion operatic showdown. The cinematographer Stephen H. Burum, whose several other films for Mr. De Palma include "The Untouchables," gives "Raising Cain" a crisp, handsome look that helps to ground its fanciful story in some sort of reality. As it means to, the film has the strange, perfect clarity of a dream.

Some of "Raising Cain" really does consist of dream sequences, although of course Mr. De Palma has fun by failing to specify where they begin and end. Carter has his own set of hallucinations, involving Cain's evil aphorisms ("The cat's in the bag, and the bag is in the river") and Carter's attempts to shake off very persistent childhood demons.

Carter's wife, Jenny (Lolita Davidovich), is confused in her own right once her former lover Jack (Steven Bauer) makes an unexpected appearance on the scene. Jenny's purchase of two clocks, one for Jack and one for Carter, affords the director many opportunities to play tricks upon the audience, as do Jenny's sexual reveries about Jack. These sequences, also startlingly photographed, have a way of featuring Carter lurking somewhere in the back of Jenny's mind.

Mr. Lithgow has a field day with an indescribably loony role, one that amounts to an open invitation for scenery-chewing excess; instead, this subtle, careful actor stays very much in control. Even in a woman's black wig, barefoot and wearing a raincoat, Mr. Lithgow manages to seem remarkably restrained. Miss Sternhagen also stands out as someone who is very much on the film's peculiar wavelength, although by the time she appears, fairly late in the story, it has all gone well over the edge. It is she, as someone who knew Carter and his even crazier father (also played by Mr. Lithgow), who reveals that their early troubles were once the basis for a television mini-series. That's one of the few things in "Raising Cain" that makes perfect sense.