FOR WHEN YOU HAVE TIME FOR A QUICKIE

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | June 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

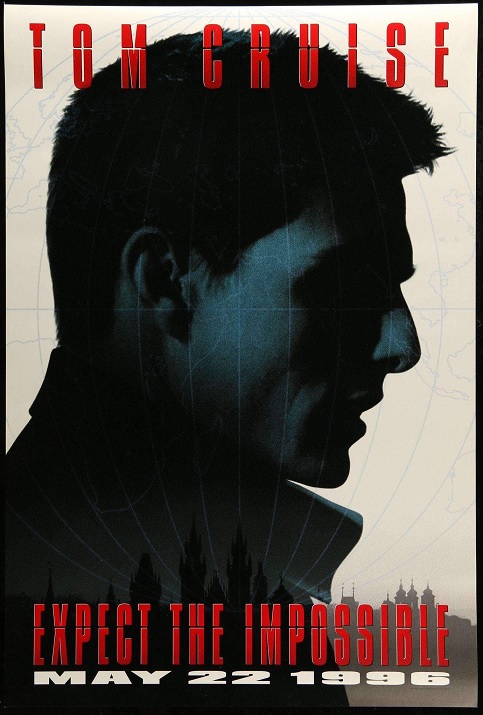

If you told those of us who saw Mission: Impossible in theaters in 1996 that, 25 years later, the series would still be going strong, with Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt having outlasted two James Bonds, two Supermen, and three Batmen, we probably would have called you an idiot. It’s not that the movie (which, to celebrate its anniversary, has just been rereleased in a remastered new Blu-ray edition) wasn’t a sizable hit — it was — but it was also initially held at something of a remove by critics and audiences alike. It was the kind of smash-and-grab blockbuster that made a huge chunk of its box office in its opening few days and didn’t seem to care about word of mouth. That type of hit is, of course, pretty much all we have nowadays, but back in 1996, it wasn’t exactly a mark of quality.Critics, who’d always been divided on the work of director Brian De Palma, saw Mission: Impossible as a movie that showcased his expertise with suspense, but one that didn’t have much personality to it. The action setpieces (mostly) received their share of praise, while the screenplay (credited to Robert Towne and David Koepp, and reportedly revised constantly throughout production) got knocked for being confusing or nonsensical. Many fans of the original series were disappointed that this new version was less about teamwork and spycraft and more about Tom Cruise jumping off exploding trains. (Some were also upset that this film decided to make Jim Phelps, the ostensible hero of the original show, a villain.) The then-small-but-growing ranks of the Extremely Online chuckled over the picture’s representation of how the internet works. Its CinemaScore grade was a mere B+ … which, in the world of hyperinflated CinemaScore grades, is generally cause for concern.

No, there was definitely something uncool about Mission: Impossible. It was somehow both too smart for its own good and also, weirdly, not smart enough. Besides, Tom Cruise: action star? What? It’s hard to remember now, but Mission: Impossible was an odd choice at the time for the actor, who had built his stardom through a savvy combination of mainstream prestige pictures and pop hits but had never really been an ass-kicking action hero. In Top Gun, he flew jet fighters, while in Days of Thunder, he raced cars; in those movies, the action came from the machines, not the people. And despite his incredible box-office run, Cruise avoided sequels. Mission: Impossible, which he produced, seemed very much like the type of flick designed to establish a franchise, an odd choice for a performer whose white whale at the time was not so much box-office success as Oscar glory. (At the time, he’d only been nominated for 1989’s Born on the Fourth of July, though he’d starred in numerous Oscar-anointed films, such as A Few Good Men and Rainman. However, he’d soon be nominated for that year’s Jerry Maguire and, not long after, Magnolia. He still hasn’t won that Oscar.)

That odd choice would soon prove prophetic. It didn’t seem likely at the time that the industry would one day mostly abandon the star-driven, medium-budget hits that had been so important to Brand Cruise — that everything would eventually become subsumed into franchises and so-called IP, and that a star’s earning potential would become wedded to their ability to play the same, extremely familiar character over and over again in multiple installments of the same film series. Did Cruise himself recognize that this would become the way of the world? Probably not. He still had a good decade of star turns ahead of him. Jerry Maguire was still in the future, as were Minority Report and Collateral and War of the Worlds (and, of course, Magnolia, arguably his greatest performance). But one day, after his public image exploded, he’d wind up needing Mission: Impossible to help him claw back to relevance — and to some modicum of public affection.

In the period following the original’s release, however, you could sense the series struggling to find its footing. Mission: Impossible II, which came out four years later, was tonally very different from the first one. Director John Woo went for straight-up action ballet, with Cruise doing acrobatic gunplay while performing elaborate motorcycle stunts, the rest of his team essentially reduced to bit parts. Six years after that, the third entry, directed by J.J. Abrams, went dark and shaky-cam, entertainingly upping the explosions and the personal backstories. I would argue that the series didn’t fully hit its stride until 2011’s Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, which in many ways restored the central idea that had made the original so effective.

So, what was that idea? And how has it endured so long? Is it just, you know, stunts?

Not quite. Mission: Impossible delivered a new spin on properly utilizing what was then Cruise’s thermonuclear star power. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the actor represented a fresh-faced, can-do macho ethos; this was a far cry from the musclebound strongmen and grizzled wiseasses who dominated action cinema. But by the mid-’90s, the Age of Irony was fully upon us, and Cruise’s all-American appeal needed some complication. A little of this guy went a long way: Let Cruise be too confident, too capable, too smirking and cool, and you ran the risk of silliness and annoyance. (This is why Mission: Impossible II, by the way, for all its financial success, kind of stinks.) The man could no longer grin his way through his challenges.

The trick, it turned out, was to add a bit of slapstick. Tom Cruise was a handsome, physically gifted supernova with a thousand-watt smile, but the key to making him a relatable action star was, well, to humiliate him a little. The first Mission: Impossible gave us a hero whose confidence gets him into ridiculous situations that make him look foolish: What makes the infamous Langley break-in sequence so immortal isn’t the intricate derring-do of the heist itself; it’s the fact that Ethan Hunt winds up anxiously hovering two inches off the floor, desperately flapping his arms about — because there are few things more satisfying in modern mainstream cinema than the sight of Tom Cruise looking like a total dork. And weirdly, he seems to know it. For all the theatricality of his performances, Cruise is great at deadpan.

This might also be why De Palma made such an ideal director for this material, and for this star. No auteur was better at undercutting his protagonists, at turning his heroes into marks, cuckolds, dupes, and dopes. Mission: Impossible is much more of a Brian De Palma film than it gets credit for being. Certainly, the director loves the demonic artifice of cinema — his work simultaneously mines it for aesthetic power while purposefully highlighting its inherent phoniness — and with their vast array of costumes and masks and breakaway walls and falsified surveillance images, what are Ethan Hunt and his colleagues but a bunch of amateur filmmakers who also happen to be professional spies? Tied into this embrace of artifice is also a dedication to the old-school suspense setpiece — silent, carefully choreographed, focused on details — of the kind that these movies have deftly woven in with the more typical big bang-boom of modern action spectacle.

Ethan even becomes, for a while, one of De Palma’s classic sexual marks. The film isn’t just about Ethan and his team’s betrayal by their leader, Phelps (Jon Voight); it’s also about Ethan’s betrayal by Jim’s wife, Claire (Emmanuelle Béart), with whom he clearly has a romantic connection. By the end, when Ethan discovers that Claire has been working with Phelps all this time, the deception genuinely stings. A sex scene was reportedly shot and then cut from the finished film, but the point still comes across: It’s in Ethan and Claire’s longing glances, in their gentle kisses and caresses. Mission: Impossible played a little demure in 1996. Today, it feels downright heated.

Perhaps it’s this hybrid quality — as an action flick with a flair for the perverse and the intimate, a star vehicle with a deeply weird sensibility — that makes the first Mission: Impossible hold up so well. Perched at that moment, when everything in the industry began to change, it’s a surprisingly slippery movie, not quite one thing and not quite the other.

It's no wonder Ethan Hunt looks so troubled as he's offered a movie to watch on the plane in the film's final shot. His mentor had perversely turned traitor, and now Ethan knows the story inside and out. Would Ethan ever allow or find himself to be as corrupt as his mentor? As if being woken from a De Palma-style nightmare on the plane at the end (remember Jim Phelps' bloody Carrie-and-Deliverance-like hand coming toward Ethan in a dream?), Ethan's troubled look leaves the question hanging. A ghost, as Kittridge might call him, and yet obliged, like Besson's Nikita, to "consider the cinema of the Carribbean," or "Aruba, perhaps?"

Here's more from Franich:

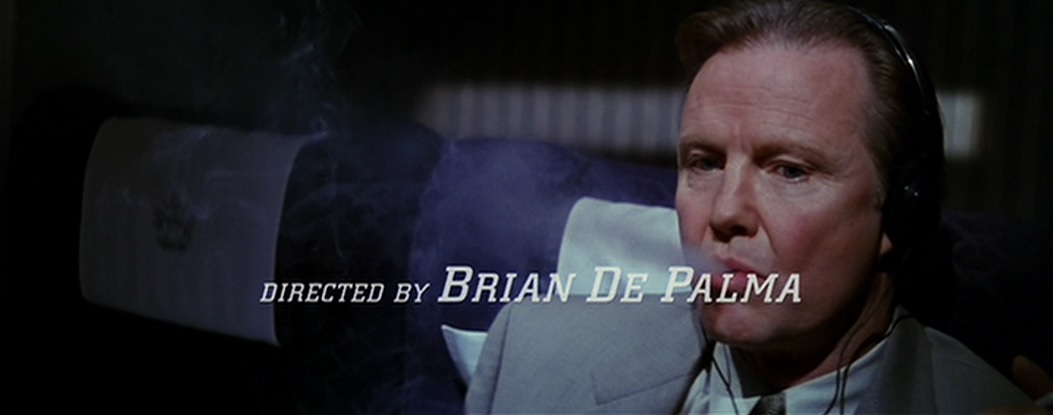

Jon Voight was 57 when Mission: Impossible hit theaters 25 years ago, but everything about Brian De Palma's movie renders him older. Gray-haired Jim Phelps wears suspenders that are painfully '80s — and May 22, 1996, was one of the last times in history nobody wanted to look '80s. Quite a contrast with Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise), Jim's fellow secret agent, a walking smirk whose leather jacket shines brighter than his hair gel. Everyone else in Jim's Impossible Mission Force is cool: stylish European women, brash American dudes, thirtysomethings right at that perfect midpoint between being Young and being In Charge.They just got done running an op in Kiev. Jim missed it, taking an expense-account job-cation to run recruitment out of the Drake Hotel (oooh!) in Chicago. "Guy's getting soft in his old age!" Ethan says. It's just a bit of ribbing, because Jim is his mentor. It's also a generational threat. Jim's wife, Claire (Emmanuelle Béart), is on the team, too. She's younger than Ethan, and when he makes his joke about old man Jim, Claire flashes her husband an unreadable glance. Does she feel sorry for him? Is she seeing him the way the boys do — a good man, yes, but a bit paternal? In the opening scene of Mission: Impossible, Ethan injects an unconscious Claire with a syringe and then cradles her cheek. Part of the job, of course, yet De Palma's romantic framing demands subtextual perversion. Don't these two just make more sense together? And then Jim dies in the first act: a tragedy, unless you're a human with a pulse who came to a Tom Cruise movie for Tom Cruise.

Jim Phelps was a main character on the original Mission: Impossible, played by Peter Graves across a couple iterations from 1968 through 1990. It's not clear whether Voight is literally the same character; canon barely mattered in 1996 outside the Star stuff, and Voight was a decade younger than his predecessor. But the general audience carried the memory of Graves' silver-haired monotone right into the movie. What was that memory, exactly? The other day, I went to Paramount+ to find a random Mission episode from February 1971 — almost as far from the movie as the movie is from us. In "Kitara," Jim's team goes to "the African nation of Bocamo," where "a colonial minority" practices "severe racial segregation." What this means, in dramatic terms, is Jim goes undercover with a ridiculous accent, because the bad guys speaks Villain English. Meanwhile, his crew uses a special pill on the malevolent military governor (Lawrence Dobkin) that turns his white skin black.

It's crazier than it sounds, with a plot that requires the Leonard Nimoy character to say (undercover, but still): "I am 1/16th Black." I don't bring this up to demand a cultural reckoning with a half-century-old TV episode (which was anti-apartheid in spirit if helplessly tone-deaf in execution). The thing to notice is how Graves' expression doesn't waver once. Here's Jim Phelps in an off-key racial-hysteria cartoon — walking around a corner of West Africa that looks like some producer's Beverly Glen courtyard — and he greets every incident with the same indifferent newsman grimace.

Elsewhere in the early '70s, Voight was going river-mad in Deliverance, and De Palma was putting Hitchcock under the knife with Sisters, and screenwriter Robert Towne was busily composing Chinatown. The fact that all three New Hollywood-ers wound up working on a TV adaptation about Tom Cruise's fitness regimen was end-of-cinema talk in 1996. But there's a subversive rage in the first Mission: Impossible, totally absent from the later films in the franchise. Everything goes wrong in the opening embassy mission. Nerdy hacker Jack Harmon (Emilio Estevez) gets skewered in an elevator — a heart-dagger for any Mighty Duck kids who saw Coach Bombay laughing with Cruise in the trailer. The rest of the team dies, too. It's one of the best first half-hours in any thriller. You only gradually realize how many different counter-plots were playing out in front of you. There's the embassy party, and a traitor stealing valuable information, and the IMF team stopping that traitor, and another IMF team setting up this whole operation to smoke out a mole in the agency.

At the center of this mystery maze is the mole: Jim Phelps, legendary hero of Mission: Impossible, a friend-killing backstabber who sells out the entire global security apparatus for some retirement cash. Between Jim's "death" and his surprise reappearance, the movie loses a step. Everyone remembers the hanging computer hack, which is a blast. But the screenplay is officially credited to Towne and David Koepp, plus a "story by" credit for Steven Zaillian and rumors of script doctoring by everyone in town. You feel Mission's many cooks, the sense that Cruise's star power is gluing together some missing motivation. The dynamic between Ethan and Claire doesn't land anywhere it should: not romantic, not sexual, not suspicious, really nothing. They stitch together a renegade squad with Luther (Ving Rhames) and Krieger (Jean Reno). They fly to America, to London. They prepare a final sting to flush out the real bad guy.

And then Jim finds Ethan. He peddles an alibi, blaming the team's death on Kittridge (Henry Czerny). Ethan doesn't buy it. He can see the truth. We watch Jim's shooting from another angle. The old man fires his own gun, and reaches for blood packs. The look on Voight's face is astounding: a primal scream, a smile unlike any smile Tom Cruise has ever grinned (except maybe amid Interview With the Vampire's erotic vanquishment). He is getting away with something awful. He loves it.

In this late Ethan-Jim conversation, Mission rediscovers all its layers. They're both fooling each other, and their lies ring true. Why, Ethan wonders, would Kittridge have done all this? "Why, Jim?" he asks, "Why?" Jim's response has the quality of confession:

When you think about it, Ethan, it was inevitable. No more Cold War. No more secrets you keep from everyone but yourself, operations you answer to no one but yourself. And then one day, you wake up, the President of the United States is running the country without your permission. The son of a bitch. How dare he? Then you realize it's over. You're an obsolete piece of hardware not worth upgrading. You've got a lousy marriage and 62 grand a year.

"It was inevitable," says the hero of an old Mission: Impossible who is now the monster of the new Mission: Impossible. Every franchise gets the religious treatment now, so it's hard to think of any comparable event in recent years. Imagine if Luke actually was a bad guy in the new Star Wars movies, or if a Harry Potter sequel in 10 years finds Hermione peddling Ministry of Magic secrets to some breakaway Durmstrang alumni. A cosmic perspective on the last 25 years of movie franchises might declare that movie sagas have gotten more serious. But that's mostly cosmetic. James Bond keeps saving the world, and even Evil Superman is just a prophecy. (One Terminator turned John Connor into a bad guy, a decision offset by how Arnold Schwarzenegger's robot keeps getting nicer.) There are exceptions, and cultural reckonings nudge recent franchise expansions to reconsider their heroes in a broader context. But according to original series star Martin Landau, one original plan for the first Mission movie was to kill off the entire TV show cast in the opening reel. Today there would be social media scandals, actors and fans uniting with anxious executives to ensure a proper nostalgic celebration. In 1996, Mission: Impossible could still reserve its fan service for bleak jokes. "Good morning, Mr. Phelps," Kittridge says when the jig is up. That greeting started almost every episode of the show. Here, it sounds an awful lot like Gotcha, sucker.

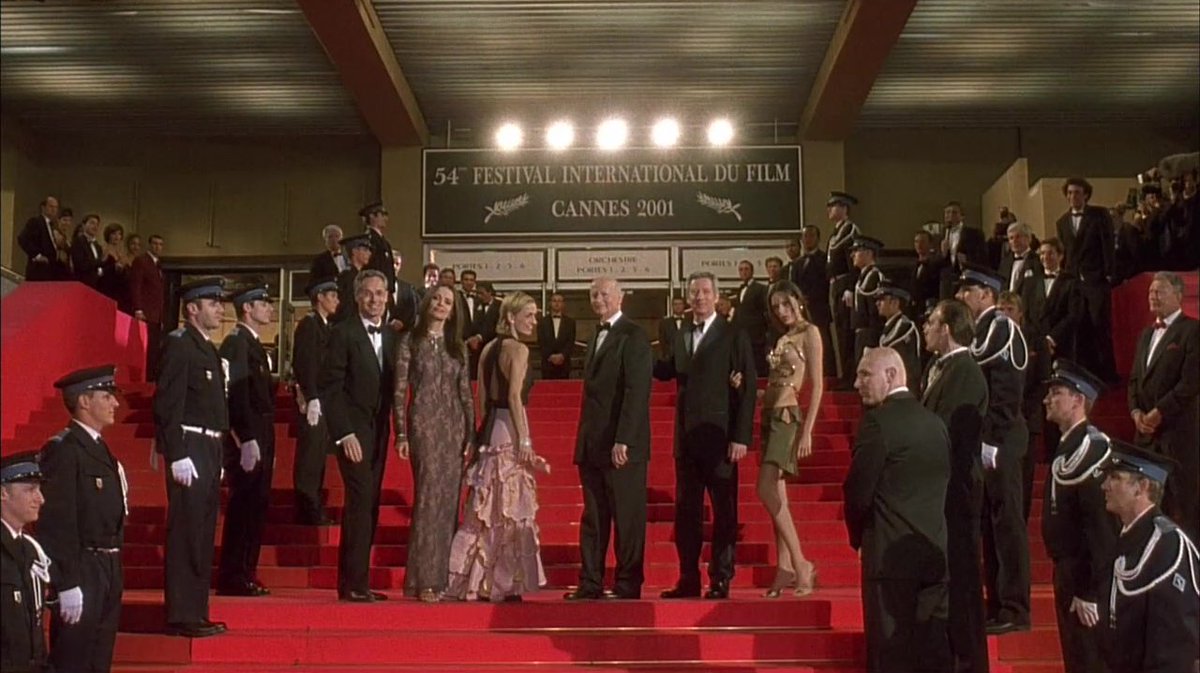

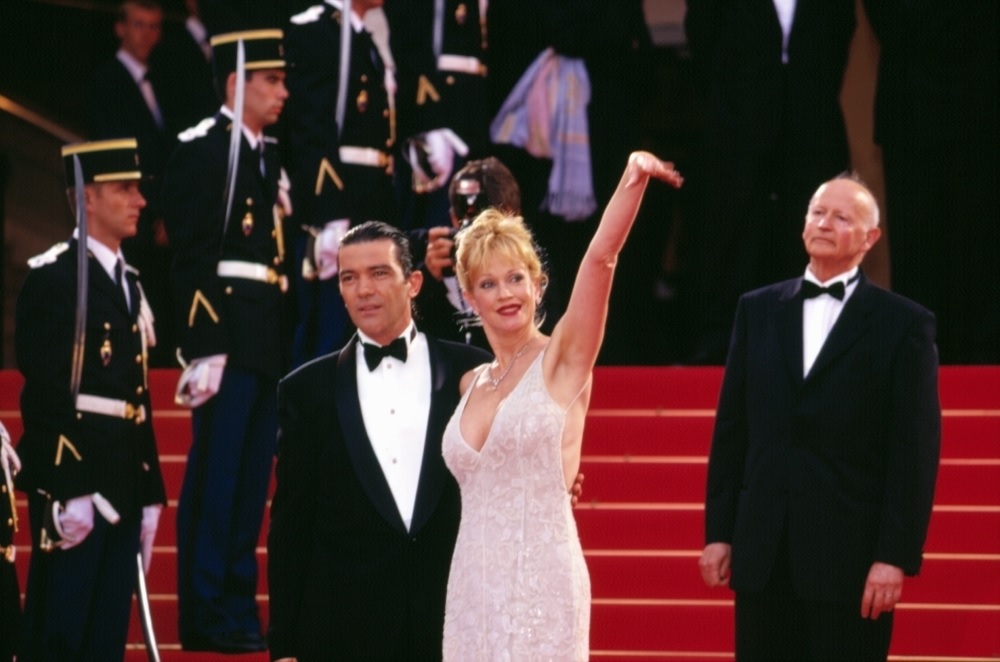

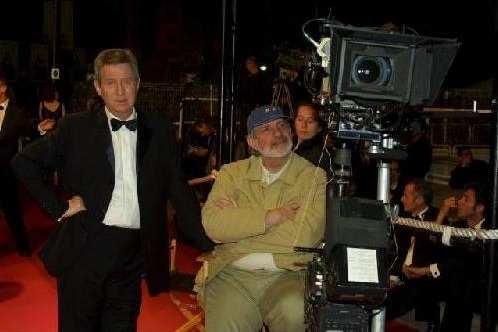

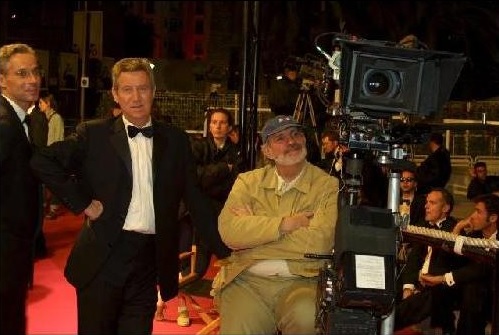

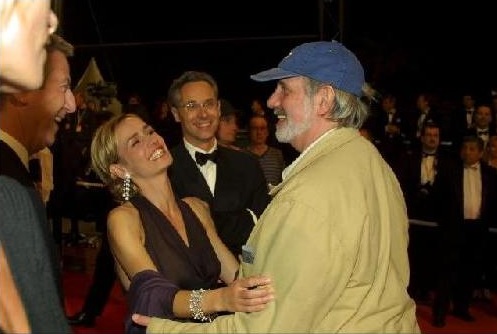

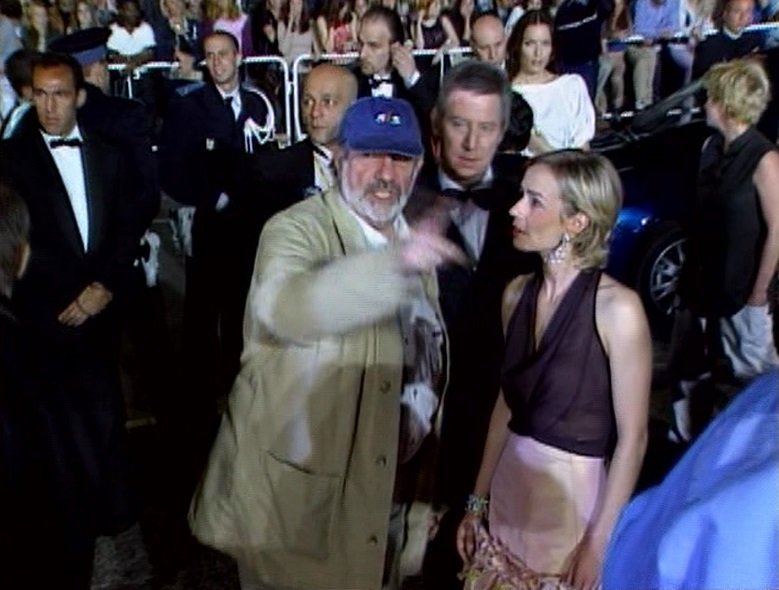

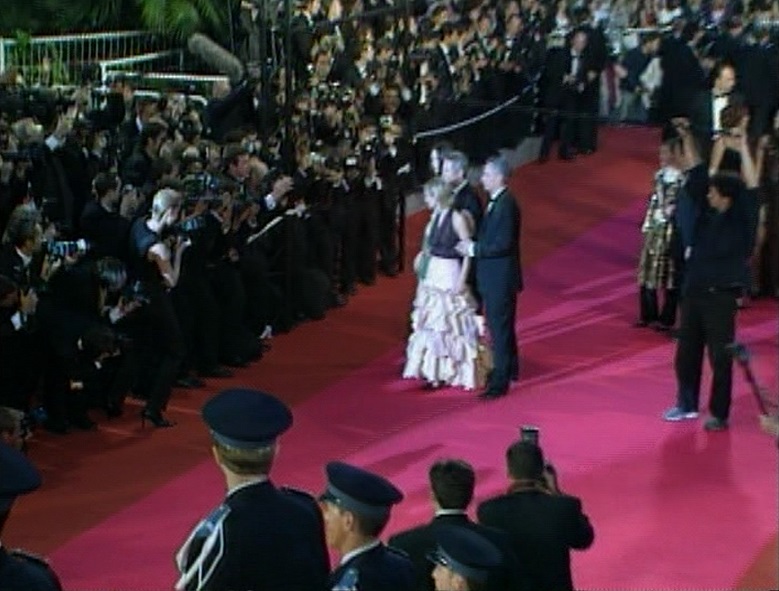

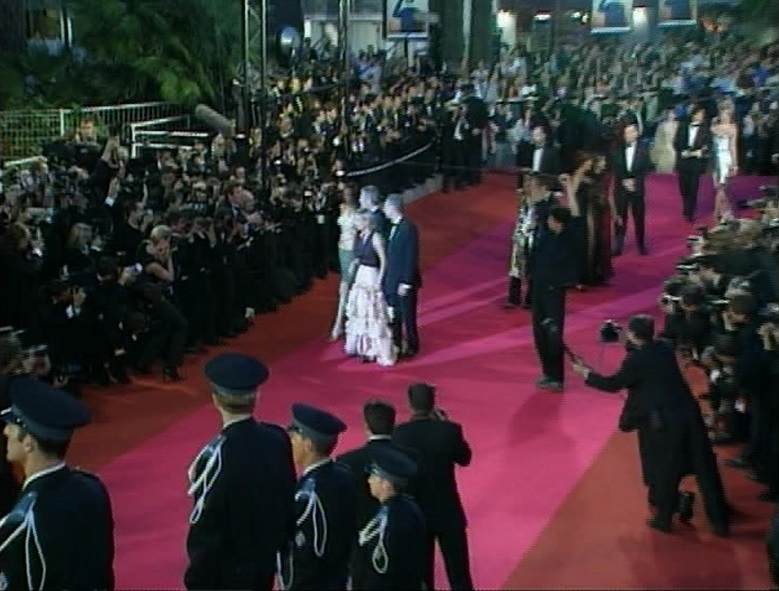

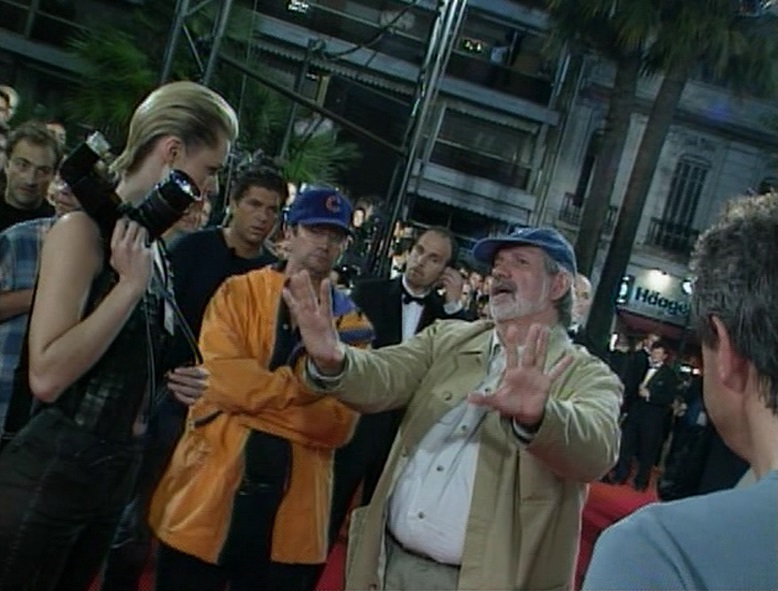

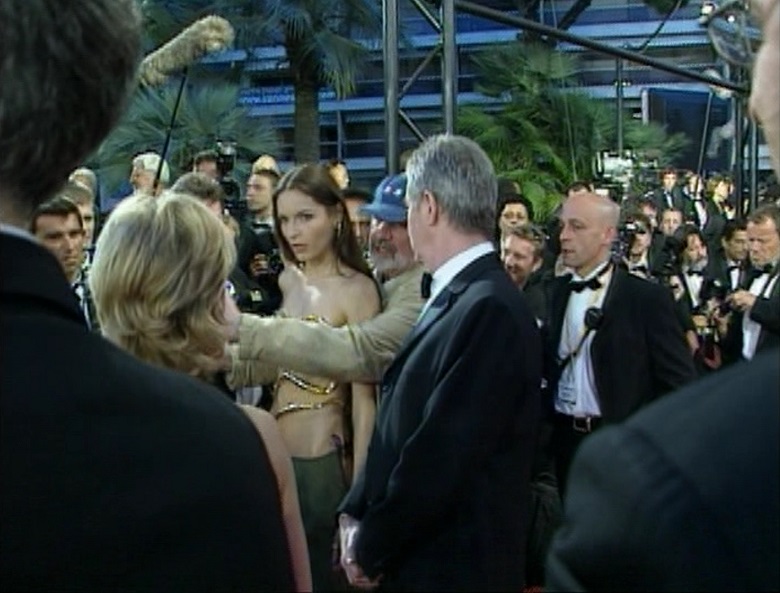

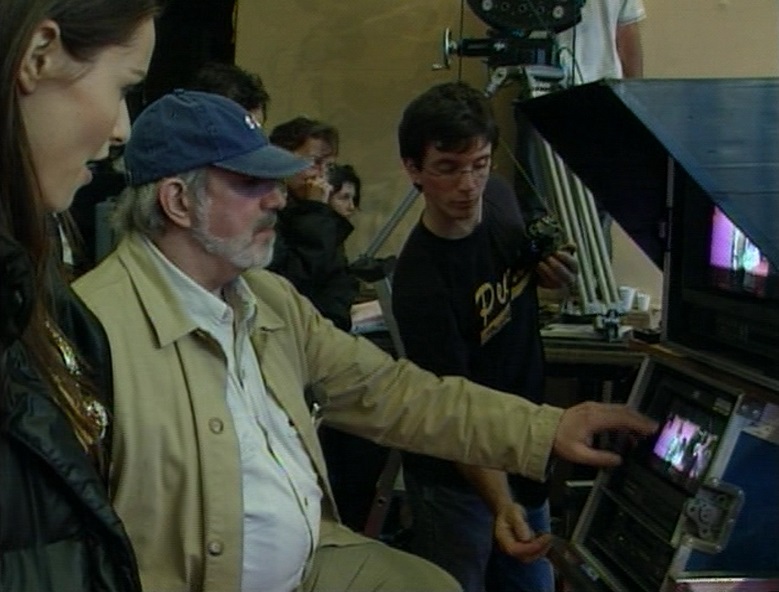

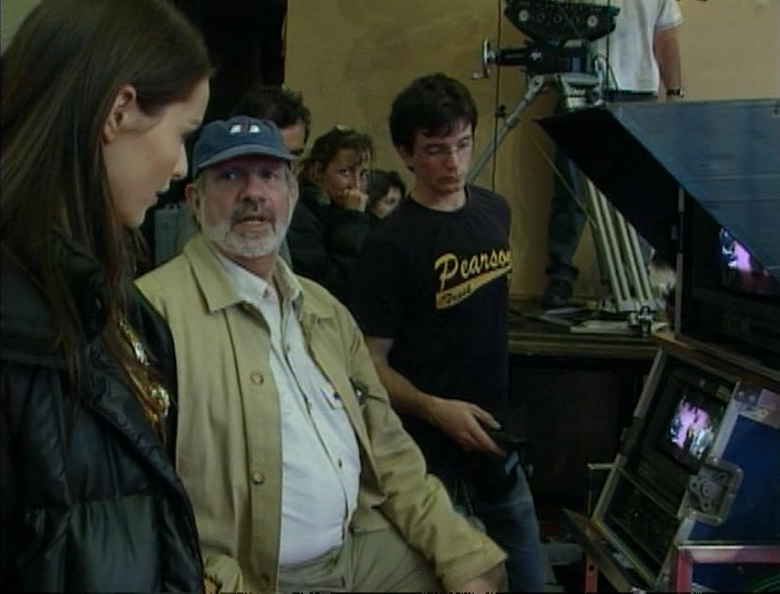

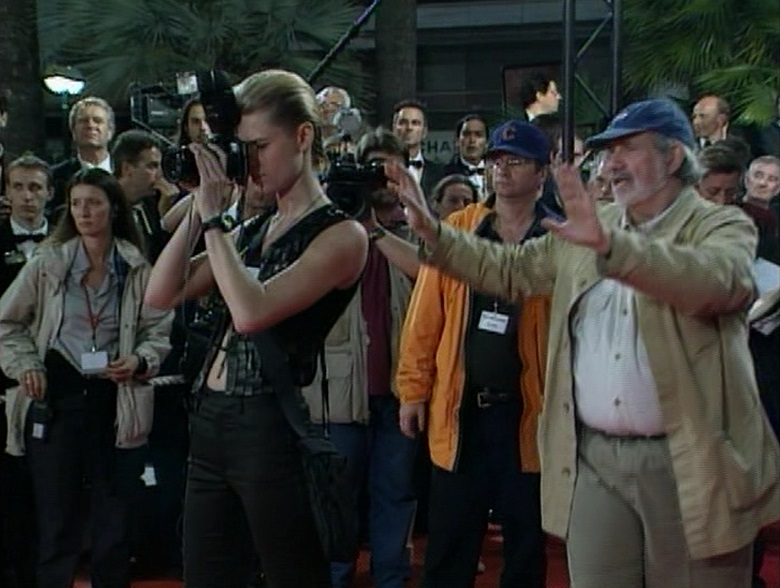

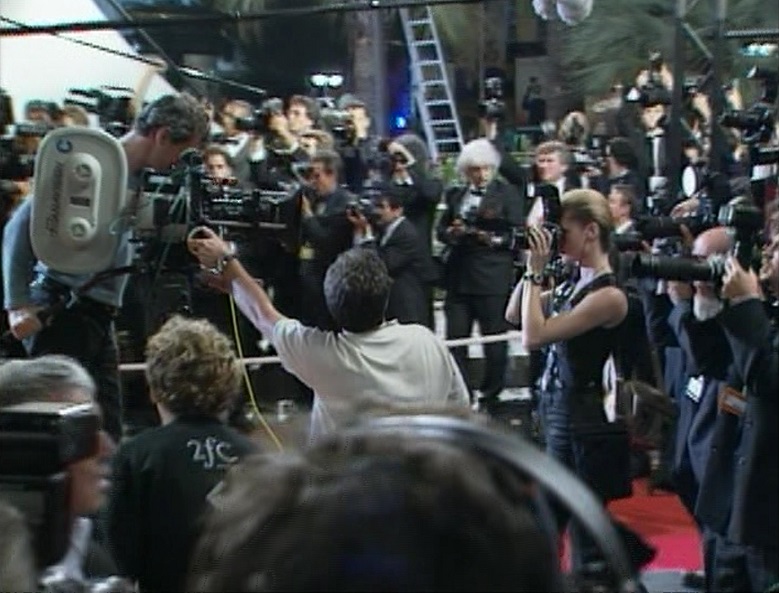

CANNES — Having shared the limelight with new artistic director Thierry Fremaux and new managing director Veronique Cayla throughout the just-concluded Cannes Intl. Film Festival, Gilles Jacob stood on the Palais steps alone Tuesday — for his bigscreen debut in Brian de Palma’s “Femme Fatale.”On the Sunday night before, during the closing awards gala, Jury President Liv Ullmann announced that the director's prize would be shared by David Lynch for Mulholland Drive, and Joel Coen for The Man Who Wasn't There. Although Antonio Banderas had already completed filming all of his scenes in Femme Fatale before Cannes, and does not appear in the opening sequence, he was at the festival to accompany his wife, Melanie Griffith, who was the Cannes guest of honor that year. Griffith received the Festival Trophy on May 19th at a dinner reception following a screening of Working Girl. Melanie and Antonio then made a splash for a second night in a row on the red carpet for the Cannes closing night gala:Playing himself, the fest prexy greeted helmer Regis Wargnier, actress Sandrine Bonnaire, producer Yves Marmion and the cast and crew of Wargnier’s “East West” as they climbed the red-carpeted steps for a specially staged opening sequence of De Palma’s $35 million thriller.

The two-day shoot, a day after the film festival closed, took three months to prepare, according to Marina Gefner, who is producing with Tarak Ben Ammar. Ben Ammar’s Quinta Communications fully financed the film.

De Palma persuaded Wargnier to participate “because they are friends,” said Gefner. Some 1,000 extras were hired and almost 200 press photographers who had been covering Cannes were persuaded to stay on for the film shoot. Car rental companies and the local police also were called upon to take part.

As for Jacob, he was “fantastic and very professional,” Gefner said.

“It was a long night. We started at 8:30 p.m. and went on until 6 in the morning, but he remained right until the last shot,” she said.

In a May 24, 2001 report on French TV channel TF1, Gilles Jacob said that De Palma first brought up the idea of filming at the festival at a dinner the year before in which he was accompanied by Antonio Banderas and Melanie Griffith. "De Palma is a great director," Jacob told TF1. "It's a pleasure to be doing this."

A Nice Matin article from that week described De Palma's tendency to jump out of his chair and direct the actors closely on a moment's whim or inspiration. According to TF1, Wargnier enjoyed his role as much as Jacob, saying that it is always interesting to be on the other side of the camera and study another director's methods. Wargnier, who says that he and De Palma have long admired each others' work, was also consulted by De Palma about locations prior to the shoot in Paris. "De Palma and I became friends 11 years ago," Wargnier told TF1 in 2001, "and he enjoyed my film East-West so much that I couldn't refuse." Rebecca Romijn-Stamos (as she was known at the time of the interview) told the station that De Palma is a legend. "He listens to my ideas," she continued, leading into a laugh, "but ends up doing what he has in mind."

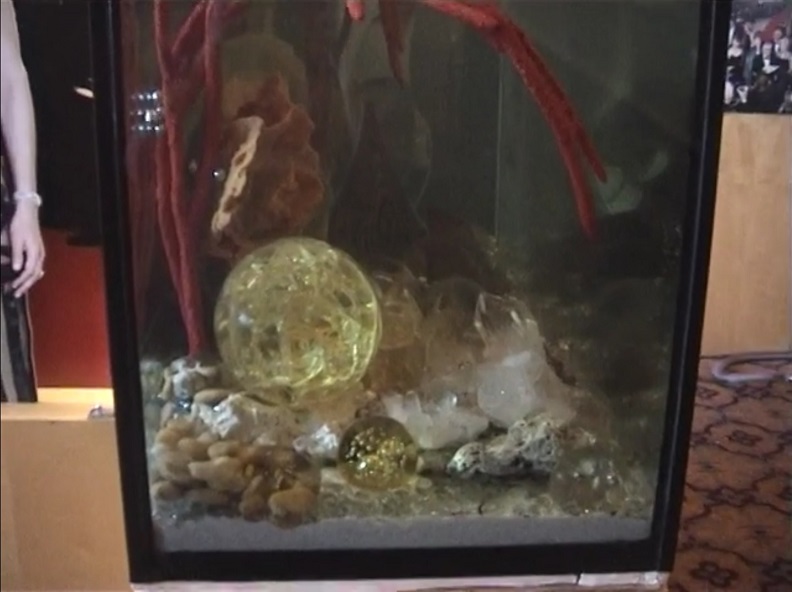

I was surprised this week to find a video on YouTube, posted a couple of years ago by Aquadia Scandia Aquariums Cannes FRANCE, showing a team installing an aquarium inside the Palais des Festivals. The aquarium they installed during the day the Monday after the festival appears to be a smaller version of an aquarium that was already a central part of the building's lobby. In this movie aquarium (which the camera in Femme Fatale glimpses only briefly as it passes by a couple of times), the team appears to have included a crystal ball. In the final film, the aquarium can be seen most clearly in this shot, next to Rie Rasmussen:

Tom Cruise: I remember one night I went over and there was Brian De Palma. And so we had dinner. The three of us had dinner at this place up the street. And we were just talking about movies, and there was Brian, and I’d seen all of his films, and I went home that night – you know, Mission was on my mind; I was actually preparing, also, I was prepping Interview With The Vampire at that time, and working on a few other things. And I went home that night and I stayed up for about 14 hours and I just got all of De Palma’s movies and I restudied all of his films.Christopher McQuarrie: For De Palma movies, we're talking about Carrie, Blow Out...

Tom Cruise: Yes.

Christopher McQuarrie: Dressed To Kill...

Tom Cruise: Untouchables...!

Christopher McQuarrie: Untouchables.

Tom Cruise: Okay. And... I just went, "Oh my gosh," that... "he’s gotta direct Mission: Impossible."

One of the most iconic shots from the first Mission: Impossible film nearly did not happen because Tom Cruise was having a difficult time pulling it off.In a series of snippet interviews the star did with director-screenwriter Christopher McQuarrie for Paramount’s anniversary Blu-ray of the 1996 film that kick-started the billion-dollar franchise, Crusie explained that he kept falling too far when he was suddenly lowered via a cable into CIA headquarters vault.

Cruise said he was unable to balance fast enough on the cable.

“We were running out of time, and I kept hitting my face and the take didn’t work,” the actor said, explaining he finally asked crew members for British pound coins to put in his shoes as counterweights.“[Director] Brian [De Palma] said, ‘One more and then I am going to have to cut [into the moment] and do it,'” Cruise said. “I said, ‘I can do it.’ And I went down to the floor, and I didn’t touch. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, my gosh. I didn’t touch.’ And I was holding it, holding it, holding it, holding it. And I’m sweating and I’m sweating. And he just keeps rolling.”

Cruise said he realized in that moment that they got the shot and De Palma was now just messing with him. Finally, De Palma began to laugh and called cut.

In another interview section, Cruise said he was stuck in a traffic jam in Japan while marketing another film when he got the pitch call from De Palma for Mission: Impossible.

Yet as "Mission: Impossible" turns 25 on Saturday, the scene in director Brian De Palma's thriller that continues to shock and awe is Cruise's controlled aerial stunt as Hunt breaks into an impossibly secure CIA vault in Langley, Virginia.The 11-minute scene – with Cruise floating from lines in the ceiling as Hunt avoids sound, touch and temperature monitors – turbo-boosted the $3.6 billion "Mission" franchise and set the blueprint for action films to come.

The instantly recognizable CIA heist remains the most iconic moment in a franchise that boasts an overabundance of spectacle (naturally, the cover art for the anniversary remastered Blu-ray features Hunt's vault break-in).

"It's the precision, the timing and the daring," says film historian Leonard Maltin, host of the "Maltin on Movies" podcast. "Actors doing their own stunts is a Hollywood cliché that's not literally true. But Tom Cruise wants you to know that's him doing the stunt, and he throws down the gauntlet to other filmmakers and audiences."

There was no hiding who was on the wires with close shots from three cameras on the austere set. No stuntman, but Cruise in a black, short-sleeved t-shirt. The body control commands respect.

"It's very difficult to hang straight out like that," De Palma said in a 10th anniversary "M:I" interview. "It takes a tremendous amount of muscle control. Tom was able to do this and bring a kind of reality to it and really grab the audience. You see the tremendous tension he's under."

The tension is enhanced by De Palma's slick direction in the scoreless scene, as he flashes over to cohort Franz Krieger (Jean Reno) silently straining to hold Hunt's pulley system from the ceiling air duct.

The reality wasn't far from the film version. At Pinewood Studios outside London, two set workers behind the fake CIA walls utilized weights with carefully marked ropes to control Cruise's movements, moving the actor up and down.

"That looks effortless, but that's a really difficult stunt. If you drop him too far down, that's not good," Sherry Lansing, then CEO of Paramount Studios, said in an interview for the film's 10th anniversary. "That's one of the hardest stunts Tom's done."

Cruise, producing his first film from the 1970s TV series, and De Palma worked out the vault break-in details over a small model of the CIA set. These included Hunt's inverted ceiling entrance and potential heist problems to amp the drama — such as a rat in the air duct that startles Reno's Kreiger, who lets the rope loose, lurching Hunt towards the wired floor.

But the near-drop was problematic to shoot as Cruise had trouble keeping his body balanced on the ropes with the sudden stop inches from the floor.

"I kept going down to the floor and bam, I kept hitting my face. And the take didn’t work. And we’re running out of time," Cruise explained in a 25th anniversary interview from the set of the upcoming "Mission: Impossible 7" with director Christopher McQuarrie. "And it’s very physical, I’m straining."

Cruise said he asked the English stunt crew for heavy pound coins which he placed in his shoes for needed equilibrium. Naturally, in Cruise's re-telling, De Palma gives his star one more chance to pull the stunt off.

"I went down to the floor, and I didn’t touch. And I remember thinking, my God I didn’t touch! And I was holding it. And I’m sweating and sweating," Cruise recalled, explaining the strain seen on Hunt's face onscreen. "(De Palma) just keeps rolling. And I was like, I’m not going to stop."

In fact, Cruise and crew have so thoroughly redefined the title that it’s easy to forget that “Mission: Impossible” was a TV series to begin with – so one of the delights of Brian De Palma’s initial entry in the series is how eager he is to remind us of those origins. He starts his film as if it’s a TV show, with a clever, fake-out cold open that moves into what is, by any measure, a television opening credit sequence: the familiar theme song scoring thrilling moments from the show/movie we’re about to watch, many of which would be spoilers if they weren’t coming at us so rapidly. It’s a big, broad wink from the filmmaker – he knows exactly what he’s making – while also falling right in line with similar medium-blurring tricks throughout his filmography, like the dating game show that opens “Sisters,” or the ‘60s-style street theater performance documentary embedded in “Hi, Mom!” (It also feels like a casual reminder that he’s done this sort of thing before; De Palma presumably got the gig on account of his fine direction of “The Untouchables,” one of the most critically and commercially successful TV-to-film crossovers to that point.)Like many a mid-‘90s blockbuster (or, well, many a blockbuster, period) the script was the film’s lowest priority; De Palma and Cruise (making his debut as a producer) went into production without a finished screenplay, but with a pricey crew of scribes on the payroll to Scotch-tape one together. As a result, critics then and now insist it doesn’t make much sense, which is both accurate and irrelevant; for my money, it’s one of those movies where it’s less important that it all makes sense to you than that you get the feeling it made sense to someone, somewhere along the line. (“Tenet,” for the record, is the same way.)

But the plot doesn’t really matter much anyway. De Palma reportedly devised his big set pieces first, and advised his screenwriters to build a plot that would get him from one to the next; his idol Alfred Hitchcock worked the same way, and it didn’t harm his movies a bit. (The climax, with Cruise atop a fast-moving train with a helicopter in pursuit into a tunnel, was said to be Cruise’s baby, and you can feel De Palma checking out during that one.)

It’s clear that the sequence De Palma was most invested in was, not coincidentally, the picture’s most memorable: the Langley heist, in which Cruise’s Ethan Hunt and his makeshift crew of fellow “disavowed” agents have to extract an identity list from a hyper-secure computer terminal inside the CIA headquarters. It is, well, an impossible mission, but that’s what they do: slipping into the building in disguise, and lowering Hunt into a sound- and temperature-sensitive chamber. “Krieger, from now on in: absolute silence,” Hunt whispers, and (as in “Rififi,” the sequence’s clear inspiration), the filmmaker follows the instructions, eschewing both dialogue and musical accompaniment, providing only the most agonizing of sound effects. I saw this scene with a packed crowd on opening weekend back in 1996, and the impact was astonishing – the audience follows the film’s lead, holding their own breath and their own sounds in, lest they break the spell. In this scene, we see De Palma following Hitchcock’s modus operandi to a tee: he’s playing the audience like a piano, from the close-up of the approaching mouse to the push-in on the bead of Hunt’s sweat to the cutaways to the sound monitor and finally, thrillingly, the slow-motion close-up of the knife tumbling through the air.

What’s most striking about “Mission: Impossible” is how thoroughly it is, above all else, a Brian De Palma movie. From frame one, he’s having a great time putting his camera wherever the hell he wants and moving it every which way; he fills the picture with snazzy zooms, low angles, circling camerawork, point-of-view shots, attention-getting overheads, split diopters, and more Dutch angles than you can shake a stick at. (The playfulness of Hunt’s relationship with Vanessa Redgrave’s “Max” also feels like a De Palma touch – he loves a sexy lady of a certain age.)

In 1996, Mission: Impossible was all about the crafting of a sleek and wonderfully knotty thriller that tied itself up in circles while delivering perfectly calibrated thrills. Even for all the script’s high pedigree, with talent like Steven Ziallian (Schindler’s List), Robert Towne (Chinatown), and David Koepp at the peak of his post-Jurassic Park glow working on the screenplay, this movie only ever wanted to be a basic framework on which to hang one De Palma showstopper after another.

And the payoff of that approach is never clearer than in the buildup and execution of “the vault” sequence in the original movie. Narratively, there’s some mumbo jumbo reason for Mission: Impossible suddenly turning into a heist movie: Ethan Hunt (Cruise) has been burned by the CIA after a frame job suggests he killed his own team to steal half of the NOC List—a data file that comprises every undercover American agent operating in Europe. But for reasons that are never exactly clear, the list is worthless without its other half, which is stored in the belly of the CIA beast at Langley.

To clear his name, Cruise is basically going to have to double down by actually stealing the other half of the NOC list. If you’re wondering why, you’re asking the wrong question. The entire appeal of the Mission: Impossible movies is how. And the how is a wonder to behold here.

Five years before Steven Soderbergh got credit for reinventing the heist genre with his Ocean’s 11 remake, many of the conventions were implemented by De Palma first: a voiceover narration by the protagonist, listing the obstacles and worst case scenarios his team is about to face? Check. The film then cross-cutting the actual mechanics of the heist with the team still discussing how they’ll pull it off? Yep. And an emphasis on a mark whose life they’re about to ruin? Just look at that poor bastard played by Rolf Saxon, a nine-to-five schmuck who after letting himself be momentarily distracted by Emmanuelle Béart (it happens) spends the rest of his screen time vomiting in trash cans and being banished to the North Pole by superiors.

It’s all here, but most of all there is an almost giddy embrace of filmmaking craft and tension-building. For most of his career, De Palma has chased the long shadow of Alfred Hitchcock and his masterful cinematic games of suspense. While this particular Mission: Impossible scene doesn’t dabble in doppelgangers and murder—two other De Palma motifs taken from Hitch that recur elsewhere in M:I—he nonetheless achieves one of his greatest suspense sequences inside the CIA vault, and it feels wholly original.

As Saxon’s CIA analyst struggles with repeated emergencies in the bathroom, Cruise is forced to dangle from an air vent over a CIA vault with such high security that in addition to the floor being pressure sensitive, he must keep as still as possible or risk his body raising the overall temperature in the room. Meanwhile if a sound louder than a whisper is made, the computer Ethan is hoping to hack will be shut down, and all the exits in the building will be locked.

So Cruise dangles from the air for a grueling nine minutes, floating with graceful, willowy precision in a cold, sterile vacuum. With a binary color scheme of white walls offset by Cruise’s tight black shirt and silvery gray gloves, the visual palette is as intentionally muted as the characters’ lips. There is no score, almost no dialogue, and each time the decibel counter on Ethan’s wrist rises, or the temperature in the room increases by a fraction of a degree, the audience gasps.

In the same summer movie season that gave us aliens blowing up the White House in Independence Day, and a tornado roaring like it’s a goddamn lion in Twister, the restraint and intelligence of this Mission: Impossible showstopper was shocking. It still is, as the commercial side of the industry continues to go the other way—to the point where the idea of a blockbuster starring scientists chasing a tornado seems downright highbrow.

Similarly, action spectacle has leaned with an ever heavier hand on computer generated nonsense. Perhaps it’s a key reason that the Mission: Impossible movies remain a generally celebrated breath of fresh air in the Hollywood tentpole landscape. Twenty-five years since the original movie’s release, Cruise is still doing these Ethan Hunt adventures, and narratively they’ve only gotten better, with the most recent two written and directed by Christopher McQuarrie being the best in the series. Their commitment to in-camera stunts and sophisticated action set pieces that put the focus on Cruise doing dazzling feats, however, feels even more vital now than then, as action sequences costing tens of millions of dollars, with digitized superhero sprites fighting hordes of animated robots, has come to dominate multiplexes more than ever before.

By contrast, Cruise’s memories about the difficulties of shooting the vault scene in 1996 are illuminating.

“I wasn’t really balanced that well [in the air],” Cruise said in a junket interview at the time. “So there were a few times where you hit the ground and you’re holding that position. It was exhausting. Brian was ready to finally say, ‘Okay, I’m going to have to divide this into two different shots.’” Today, it’d be worse: they’d say they could do it all on a computer. Yet it was Cruise’s idea (at least by how he tells it) to turn his body into a proverbial scale, and use British currency coins as his counterweights.

“I had them hook me up, hang me, put a couple of pounds in each shoe to balance myself, because I kept falling and smacking my head on the floor,” Cruise said. “I couldn’t balance it, physically. Finally, when we did it and I got the balance right… it worked, and Brian just left me hanging there just to get all of it. We had three different cameras going.”

Lindsay Ellis: So, when we were talking about how to approach this season (since originally, the conceit of this show was that we weren't going to do any movies), Kaveh texted me this "I can't believe this exists!" And it was, of course, Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise. And that was where I was like, Oh-- well, there's a thing that firmly exists only in the realm of film, and doesn't, a little bit, have a toe in the theater (at least to my knowledge). So I was like, you know what? If we're going to cover this masterpiece, we have to look at film. And so that is why we are here.Kaveh Taherian: Yes.

Lindsey: [looking at guest host Angelina Meehan and laughing] And she's dancing!

Kaveh: I was going to say, you can't see, but Angie's dancing. She's one step short of doing a back-flip right now.

Angelina Meehan: This is legitimately one of my favorite movies. I'm so, so hyped.

Kaveh: Really?

Angelina: Yes. It's one of those movies that you hear about it, and you're like, this movie can't possibly exist. And then you see it, and it kicks ass on so many levels-- I've never shown it to somebody who wasn't immediately like, "Okay, this is like balls to the wall," and I admire it for that. So...

Sometimes, recommending a "classic filmmaker" feels a little like recommending vegetables. In an age when free time is sparse and real life is full of inherent struggle, why use the precious moments we have to watch movies that require mental taxation, sitting through slogs, or reckoning with works wholly unconcerned with basic entertainment?I promise you: You will not have this problem watching Brian De Palma, one of our most singular filmmakers concerned with the ideas of cinematic "pleasure." His prolific body of work, from 1968 until today, is full of pure entertainment, of provocative subject matter, of genres stuffy cineastes often denigrate as being lesser-than. De Palma is an all-caps DIRECTOR, an artist who blows out his frames with delicious techniques, a visual stylist of the most propulsive order.

We've curated a list of De Palma's 12 most essential films, an intriguing list of entertainment that will shock you, titillate you, and simply demand your attention. From his sleazy horror-thriller odysseys to his mainstream thrill rides to his surprisingly political experimentations, these Brian De Palma films will never bore you, will always surprise you, and will leave you wanting more. Enjoy watching...

Beginning with Alfred Hitchcock's The 39 Steps, and moving on chronologically through Robert Bresson's A Man Escaped and Stanley Kubrick's The Killing, the fourth film in Swanson's dozen is De Palma's Blow Out:

We’d venture a guess that, for a lot of folks, there’s a good chance that Mission: Impossible is their first foray into Brian De Palma’s filmography. And if all those obsession-fuelled close-ups and paranoiac split diopter shots turned your crank, we’d recommend diving into the deep end with Blow Out, arguably the crown jewel of De Palma’s career and the thriller genre, period. Jack Terry (John Travolta) is a skilled sound recording artist who works on B-grade horror films. One night, while recording some new audio, he captures something unexpected with his sound recording equipment: a gunshot, a blowout, and a car crashing into a creek. Driven by curiosity and a fervent sense that the public ought to know the truth, Jack rages against the ensuing cover-up, risking not only his life but that of the young sex worker (Nancy Allen) he pulled from the watery wreck that fateful night.

The Killing of Two Lovers writer-director Robert Machoian thought a lot during the planning of the film about “how to shoot long takes without drawing attention to the fact that it’s a long take, in and of itself.”So he went back and watched Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes for its flashy 12-minute single take opening.

“It’s very showy. And there’s a place for that. But for this film, it would have been very inappropriate to be showy at all,” he says.

The Killing of Two Lovers follows married couple David (Clayne Crawford) and Nikki (Sepideh Moafi) in rural Utah, as they work through a separation. But after Nikki gets a boyfriend (Chris Coy), David begins to unravel.

The film makes masterful use of long takes throughout, and Machoian and cinematographer Oscar Ignacio Jiménez employ it much differently than De Palma did for his Nicolas Cage conspiracy thriller. In one key moment, the camera acts as an equalizer during an emotionally fraught scene.

Avoiding traditional shot-reverse-shot coverage, the camera is instead framed on both David and Nikki as they work through an argument. This prevents the audience from choosing a side.

“The second you hold the camera, you establish that somebody is more important than the other,” Machoian explains. “But David and Nikki are equally trying to figure this out. And there really isn’t one who is in more of a position of power than the other.”

Crawford, Moafi, and Coy all have theater experience, which made pulling off these extended sequences possible. “If we didn’t have the actors that we had, we would have had to shoot it differently. Because if you do a long take with someone who can’t act, it just gets worse the longer they go with it — it doesn’t necessarily get better,” Machoian says.

Machoian is aware that long takes can be distracting to viewers.

“It felt really important to just orchestrate the performance, and allow Sepideh and Clayne to move within that frame, and as a result, hopefully not draw attention to the fact that we’ve been sitting on this shot for four minutes,” he said. “Hopefully in the end you’re so engrossed in the character drama, that it’s really kind of an afterthought.”

Filmmaker Magazine's Erik Luers also interviewed Machoian:

Filmmaker: And in the final sequence, where a big argument and altercation takes place, I read that you were stationed in a golf cart tracking the action off-screen?Machoian: That’s right. I’ve made films in the past that explore duration, sometimes duration for the sake of duration and sometimes duration due to the scene being interesting enough to force the viewer to stay in the scene and watch the arc and feel a bit trapped. While I wanted most of the scenes in The Killing of Two Lovers to primarily be two-to-three-minute one-takes, I wanted the final argument to be one long take (I can’t remember anymore if it’s seven or nine minutes). It didn’t feel right to remain static (as we had throughout the film) for that sequence. We had used a golf cart in the opening sequence of the film (where David is running from house to house), but it wound up blowing a tire while we were shooting due to how cold it was outside. We had to get the tire fixed and that took some time.

Once the tire was fixed, we used the golf cart again to shoot the final fight scene, something we shot about two days before production concluded. We didn’t have the golf cart available for any other period of time until we were able to get the tire fixed. Once it was and we knew we wanted to use it for the final fight, I told Oscar, “Look, the best way for us to do this is for you to run the camera and be framing the scene constantly”—we obviously discussed the type of framing, etc.— and “I’m going to be the one driving you on the golf cart.” I drove the golf cart, moving forward slightly depending on how the arc of the drama was unfolding between the actors, i.e. as David begins to feel isolated, I push in farther so that we could, in many ways, isolate the viewer, too, or, as David and Nikki have that brief moment together (the “calm before storm”) where he’s struggling and she realizes he’s struggling and she loves him and feels sorry for the fact that he’s struggling, and then BAM! Then the camera begins to pull back again.

It was very difficult to get right, not the least because the wheel we had gotten fixed was now constantly squeaking! And since the tension present in the scene was so high, the squeaking wheel threatened to be a real distraction for the actors. I had to be like, “I’m so sorry, this will squeak, but we need to do it this way. We can’t walk it and we can’t all of a sudden switch to handheld.” We didn’t have access to a dolly, and so I pleaded with my actors, “I need you to go with me on this,” and luckily they trusted me. When they came to watch the dailies that night, they were like, “This is amazing,” and I thanked them. For emotional purposes, we needed to have the camera establish some distance. We’d used wides and closeups for the majority of the movie, but this was the place where we needed to move in and out of those wides and closeups.