AND PETER SOBCZYNSKI REVISITS THE FILM 20 YEARS LATER FOR THE SPOOL

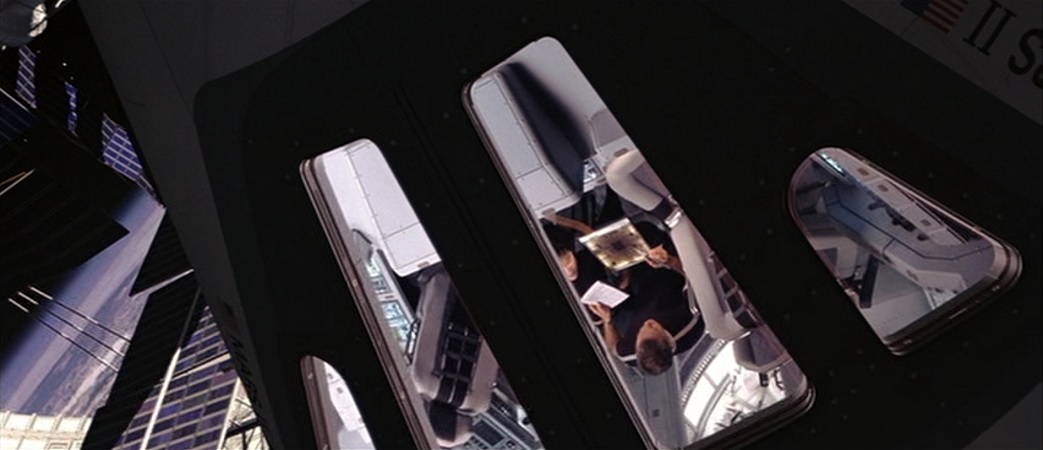

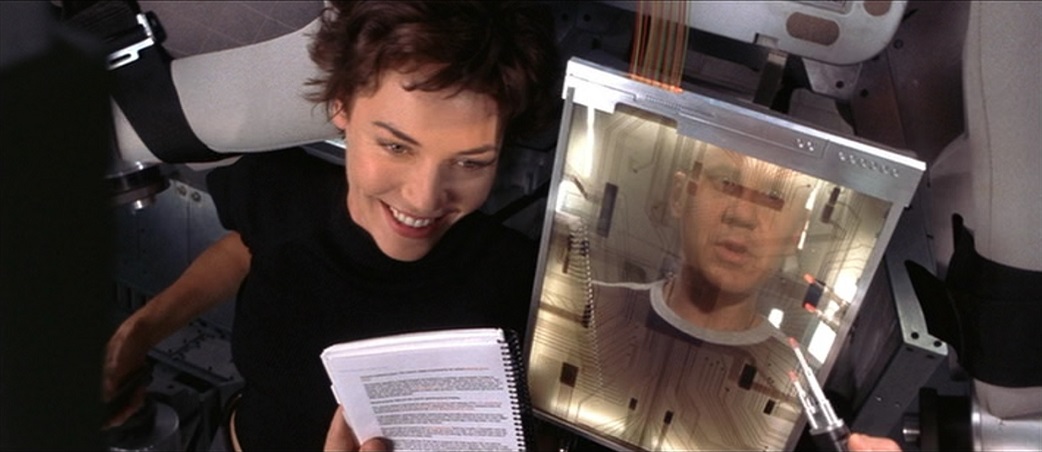

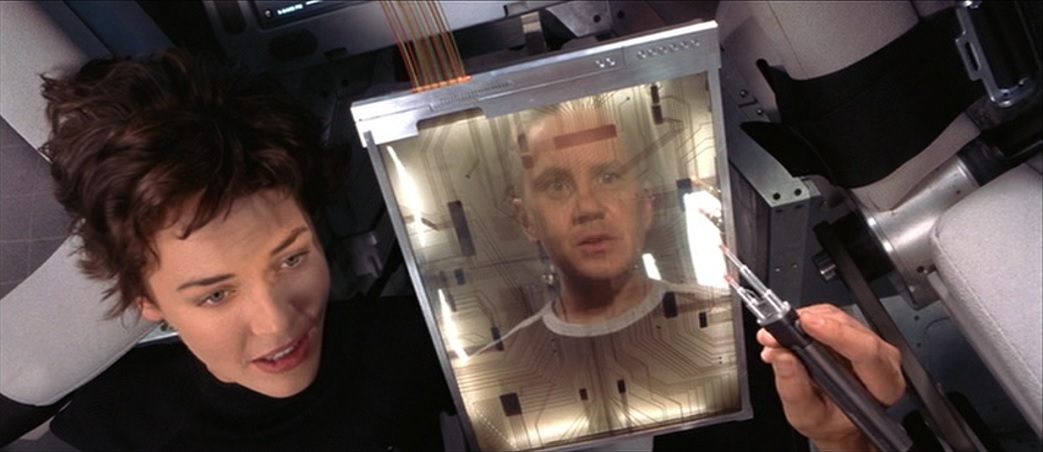

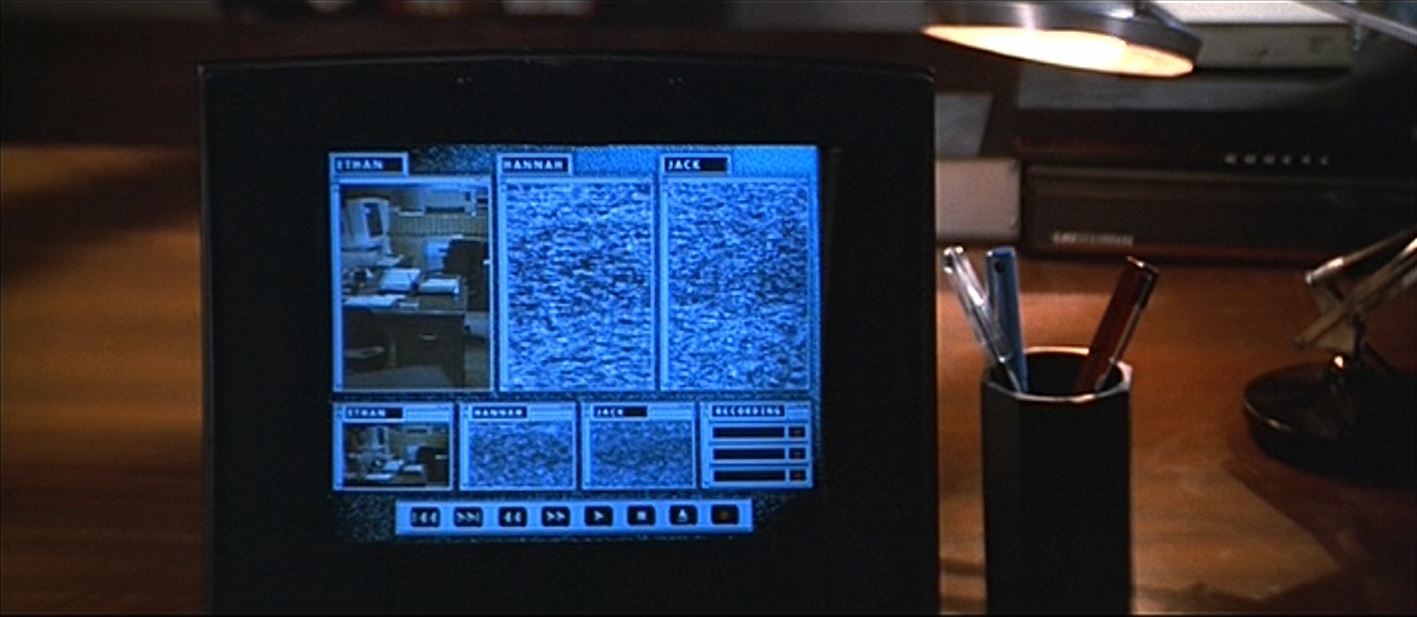

Above is a picture of Industrial Light & Magic's John Knoll, who was a VFX supervisor on Brian De Palma's Mission To Mars. The picture is part of an article by befores & afters' Ian Failes, which takes a look back at ILM's evolution sequence for the film.

"One sequence that always remained in my memory was the lengthy holographic evolution shot," states Failes. "Here, microscopic paramecia evolve – with no cuts – into other creatures including fish, lizards, crocodiles, dinosaurs, mammoths and buffalo, with hunting humans featured at the end. ILM handled this moment, which occurs while several astronauts are being versed on the origins of the universe. I asked then CG supervisor Christophe Hery, now a research scientist at Facebook Reality Labs, who supervised the work, how it was pulled off with Cari and some unique approaches to morphing."

Christophe Hery: We ultimately delivered an illustrative look, but in making it we approached it from a more photoreal perspective, going as far as putting detailed displacement on the creatures and the terrain.The difficulties (and innovations) stem, besides the length, from the fact that we had to morph animals that were shaped quite differently, from early fishes to bisons, in the context of a herd (or school).

We approached these transformations by imposing a common topology on all creatures. This was an interesting exercise for the modelers and the riggers at the time, and they did a great job at that.

A tool was written on top of Cari [aka Caricature, a tool developed by ILM’s Cary Phillips], if I remember correctly, that would weigh the morphs in various regions of the bodies (so we could have, say, legs from crocodiles and necks from diplodocus appearing at different rates). All of this could be tailored and key-framed.

We had very fine control there, per limb, but we settled, again for illustration purposes, into a more unified morph speed. The camera is panning along from above, so it became hard to read the subtleties and we wanted the message to be obvious.

The morph weights were also automatically exported from this Cari extension into the shaders, so we would get a blend of the corresponding appearances automatically.

Surprisingly, the initial push into the water was the most difficult part to render. With all these bubbles motion blurred and very close-by, we were constantly faced with camera near clipping plane issues.

The shot was truly delivered/rendered as one continuous full CG shot (in Renderman). Only the actual footage of the astronauts and the alien hand were composited in (the alien being a separate CG render pass, obviously).

PETER SOBCZYNSKI ON 'MISSION TO MARS' 20 YEARS LATER

Meanwhile, at The Spool, Peter Sobczynski looks back at Mission To Mars, as well:

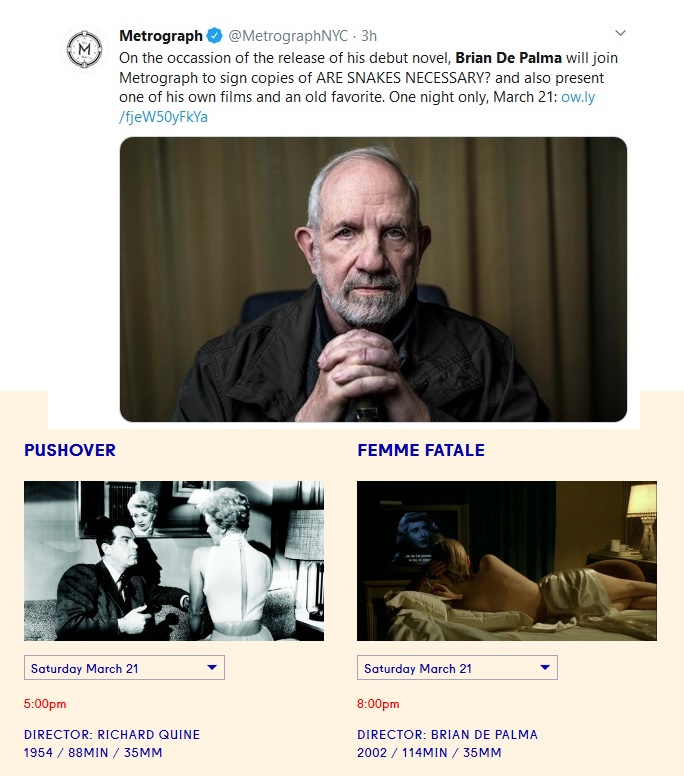

Although primarily known for dark suspense thrillers, Brian De Palma’s filmography is studded with a number of seemingly offbeat projects that one might not normally associate with the director of Carrie and Dressed to Kill. Even among his most ardent fans, though, a project like his 2000 effort, Mission to Mars, continues to serve as a bit of a bafflement. If you had to select the least suitable project imaginable for one of Hollywood’s most iconoclastic and cynical filmmakers, you could hardly do better than propose he make an expensive, optimistic PG sci-fi epic for Disney that was loosely inspired by one of their theme park attractions.The results were perhaps not very surprising. Aside from France, where it screened as part of that year’s Cannes Film Festival and was ranked #4 on Cahiers du cinema’s list of the best films of the year, it was a financial and critical failure. It’s rarely discussed today even amongst De Palma scholars. (De Palma himself only briefly touches on it in the documentary De Palma.) And yet, to watch it again 20 years after its initial release is an interesting experience.

It clearly pales in comparison to such works as Blow Out, Phantom of the Paradise, and Femme Fatale and it’s still wildly uneven in many ways. At the same time, to watch De Palma attempt to embrace new things in both genre and mindset is fascinating. It even contains one of the most absolutely spellbinding set pieces in a career that is not exactly wanting in that regard and as such, the end result makes sense in the grand scheme of his career.

After some discussion of the plot and background of the production, Sobczynski continues:

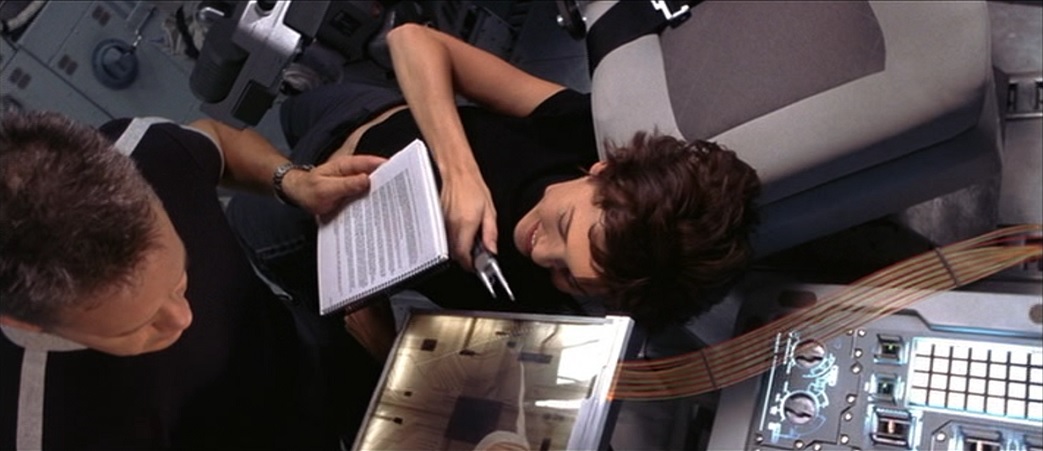

And yet, as clumsy as it can get at times, Mission to Mars does make for an intriguing addition to the De Palma canon. The film is not without its bleak and grisly moments—one scene features an exploding body that evokes the infamous finale of The Fury, albeit in a resoundingly PG-rated manner. That said, the storyline is ultimately hopeful and while it does lead to some odd moments (including what must be the least cynical deployment of the American flag in De Palma’s oeuvre), it’s surprisingly successful in evoking that kind of spirit without coming across as too forced.Better yet, the film is a visual marvel as De Palma, along with longtime collaborators such as cinematographer Stephen H. Burum and editor Paul Hirsch, creates any number of stunning images in which the constantly roving camera meshes with the feeling of weightlessness.

The highpoint of the film—indeed, the sequence that even its detractors admit is effective—is the stunning mid-film section in which a micrometeorite shower kicks off a series of ever-expanding disasters that culminates in the demise of one of the nominal stars at just barely past the halfway point. This sequence, which runs about 20 minutes or so, is De Palma at his best. It’s suspenseful, exciting, darkly funny, and constructed with jigsaw precision, and when it comes to its conclusion, it leaves viewers feeling a combination of shock and utter exhilaration at what they have just witnessed.

Seen today, Mission to Mars is just as much of an oddity as it was when it first came out and while it will almost certainly never be regarded as one of the great De Palma films by any stretch of the imagination, it does not deserve its reputation as a wholesale disaster that it gained virtually from the day it came out. (The film remains De Palma’s last Hollywood studio production as he would relocate to Europe after it came out to make films like Femme Fatale, The Black Dahlia, and Passion.)

At its lowest points, it is no worse than any number of anonymous space operas that have been produced over the years (including Red Planet, the competing Mars-themed thriller that it beat into theaters by a few months). At its highest peaks—specifically that still jaw-dropping mid-section—it serves a potent reminder of De Palma’s skills as a filmmaker. This is a film that is undeniably flawed but also undeniably ambitious and in a time when most films of this sort tend to forget to include the ambition alongside the elaborate visual effects, that does count for something in the end.