FUSION OF PERFORMANCE & FORMAL STYLIZATION MAKE THE EMOTIONS PALPABLE

Katie Stebbins' most recent Top Ten By Year zine looks at her ten favorite films of 1978 (buy a copy at her Etsy page-- it's only $6.99). Brian De Palma's The Fury comes in at #3 for her (in between Terrence Malick's Days Of Heaven at #4, and Hal Ashby's Coming Home at #2). Yesterday she shared a "Zine Peek" by posting her fantastic essay about The Fury at Cinethusiast:

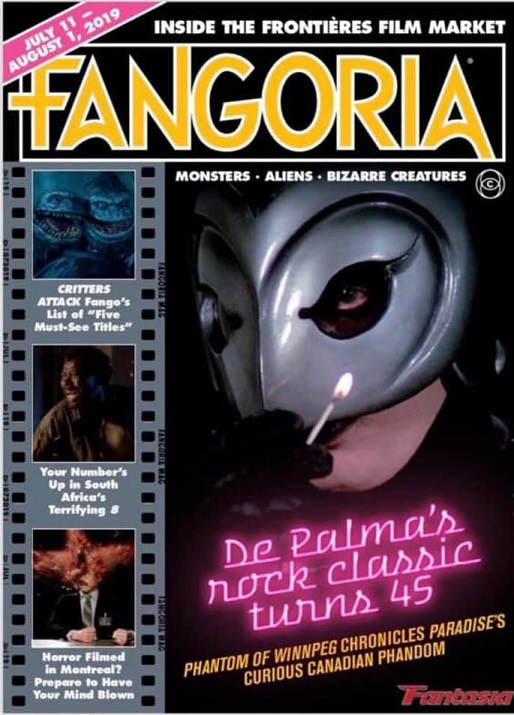

The Fury is the best X-Men film ever made, and in an ideal world it’d be considered a model for what pop cinema can be. But as Brian De Palma’s follow-up to his masterpiece Carrie it was destined to disappoint, in part because of how much they have in common. Both are based on novels about a telekinetic girl. Both feature Amy Irving as an empath who tries and fails to save a peer-in-need. And both enjoy playing at an offbeat pitch; but while Carrie does so within an unmistakable horror designation, The Fury is an ice cream sundae of genres – a coming-of-age supernatural espionage government conspiracy horror-thriller. Got all that? Add an experimentally self-reflexive cherry on top, and you have a film that audiences and critics did not, and largely still don’t, know what to make of. But to De Palma devotees (and some film devotees) it is an essential work, and an irresistible opportunity for writers to intellectualize De Palma’s relationship with cinema through cinema. It’s an exercise that often, for all its worth, makes the film itself sound like a narrative thesis. There is often a clinical disconnect that obscures The Fury’s entertaining and emotional immediacy.Watching The Fury, the main thing you notice is that even through its early slower section it is blisteringly alive, as if De Palma has some unspoken knowledge that this will be the last film he ever makes (spoiler alert: it wasn’t). It is so in tune with its own wavelength, and with the emotional stakes of its characters, that the preposterously schlocky story feels like it matters (this is greatly helped by John Williams’s momentous Herrmann-eqsue score, by turns eerie, epic, and playful. “For Gillian” is his Harry Potter before Harry Potter). It maintains the same two-fold hold on me every time I watch it — a mix of uncommonly strong investment in the characters and story, and a near-constant awe at its formal power. With an opening set-piece that involves a betrayal by way of (who else but?) John Cassavetes, a terrorist attack, a kidnapping, and a shirtless 62 year-old Kirk Douglas letting loose with a machine gun, an “all-aboard!” line is drawn in the sand. Either hop on or get ready for a long two hours.

That ice cream sundae also contains eccentric pockets of comic relief. Scenes open on oddball peripheral characters, whether it’s the cop who just got a brand new car, the little old lady who delights in helping out a trespasser, or the two security guards who pass the time by negotiating trades of Hershey bars and coffee (it also has the priceless reveal that the elderly Kirk Douglas’s ingenious disguise is to make himself look, wait for it, old!). All that Kirk and quirk gradually give way to the more sincerely executed dilemmas of the teenage Gillian (Amy Irving in a performance that belongs in my personal canon), a new student at the Paragon Institute coming to grips with her increasingly cataclysmic and all-seeing powers.

It’s trademark De Palma to toy around with the nature of cinema, and as The Fury unfolds it begins to self-engage, reaching back into itself in ways that are still hard to fully fathom. Gillian’s telekinetic link to the missing Robin (Andrew Stevens) is depicted visually, including us in the intimate and exclusive psychic link they share. Since Gillian’s visions are triggered by touch and experienced by sight, she acquires information by watching scenes play out in front of, or all around, her. She learns and we learn through her. She becomes submerged in cinema — part of the audience. Gillian experiences harrowing psychic access to Robin, and through the immediacy of the filmmaking we are given that same experiential access to Gillian. This is cinema as the ultimate form of communication, information (surveillance is a recurring theme here too, another De Palma favorite), and feeling, seen as capable of transcending the confines of the screen. As part of his brainwashing, Robin is even shown the first five minutes of the film. Cinema weaponized and all that jazz.

The tricks in De Palma’s formal playbook make all this possible. The editing (at times flickering in-and-out like a flip-book) and rear-screen projection are used to emphasize and envelop. Characters are brought together by overlapping space and sound. The camera often tracks conversation by circling around characters, knowing that the more an image changes, the more we can percieve. A bravura slow-motion sequence turns the notion of the escape scene into a cathartic reverie gone wrong. It isn’t until the end that we realize the slow-motion is in fact stretching out a character’s final moments. It is the perfect encapsulation of how De Palma, at his best, uses pure stylization to not only enhance, but become emotion. Gillian’s shake-ridden fright and confusion, Hester’s (Carrie Snodgress) heartache and longing, and Peter (Douglas) facing the consequences of his quest, are all deeply palpable through this fusion of performance and form.

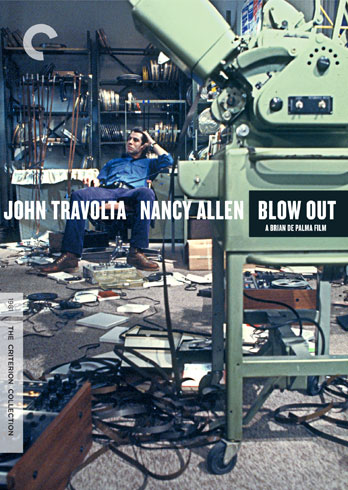

The Fury carries the devastating punch of his most emotional works like Carrie, Blow Out, or Carlito’s Way, but without the ever-lingering bleak aftertaste. It hijacks the senseless loss that came before with a vengeful ascendance so absolute it can only be called the money shot to end all money shots. And it wouldn’t be The Fury if it didn’t replay from every imaginable angle — wiping our memory out with pure orgasmic vindication.

Updated: Thursday, August 15, 2019 12:10 AM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (8) | Permalink | Share This Post