MIKE D'ANGELO: "SPLIT SCREEN IS EMPLOYED SO INFREQUENTLY THAT I ASSOCIATE IT ALMOST EXCLUSIVELY WITH DE PALMA"

A.V. Club's Mike D'Angelo analyzes the split screen sequence in today's "Scenic Routes" column:

A.V. Club's Mike D'Angelo analyzes the split screen sequence in today's "Scenic Routes" column:Resolved: Split screen is an underutilized cinematic device.That’s how I would have phrased it back in my high-school debating days. Which seems appropriate, because—as was often the case with debate resolutions—I’m not 100 percent certain that I believe it, even though coming up with arguments that support it isn’t terribly difficult. For one thing, split screen is employed so infrequently that I associate it almost exclusively with Brian De Palma, who loves to construct elaborate, suspenseful set pieces that show two or more events unfolding simultaneously. And it’s easy to wonder, after being thrilled by one of De Palma’s dual orchestrations, why he’s long enjoyed a near-monopoly on this approach, which takes such striking advantage of the medium’s intrinsic qualities—that is, of the ability to manipulate time and/or space. I still haven’t seen Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, which I believe is split screen from start to finish… but I have seen Forty Deuce, a 1982 drama directed by Warhol associate Paul Morrissey, in which, throughout the film’s very stagy second half, the frame constantly offers two separate angles of the same action, side by side. It’s mostly a distraction—as I said, I’m not entirely convinced of my own thesis here—but I’ve always sensed untapped potential in the idea.

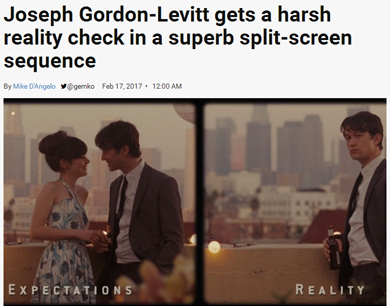

My favorite recent use of split screen, though, involves the manipulation not of time or space, exactly, but of the protagonist’s consciousness. (500) Days Of Summer is a gimmicky movie in a lot of ways, starting with the parenthesis in its title; it has an omniscient narrator, jumps all over the place chronologically, and at one point sees its hero, played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, perform an impromptu musical number, accompanied by dancing extras and animated birds. Most of this quirkiness can be filed under “cutesy,” and will either delight or irritate, according to taste. But the movie does have a more downbeat side, which comes most strongly to the fore during a brief sequence toward the end, when Gordon-Levitt’s Tom shows up at a party being thrown by ex-girlfriend Summer (Zooey Deschanel). Screenwriters Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber want to show us how what happens at the party deviates from what Tom imagined would happen, and either they or director Marc Webb decided to do so by splitting the frame down the middle, with “Expectations” on the left and “Reality” on the right...

...What finally makes this sequence so effective, though, is how credibly mundane both Expectation(s) and Reality are—a choice that the use of split screen enables. Had the two versions of the party been presented one after the other, it probably would have been necessary to exaggerate them slightly, in order to highlight the differences (especially since that almost surely would have meant discovering that the initial version is Tom’s fantasy only after the fact). Showing them simultaneously lets the viewer’s darting eyes, rather than memory, do all the work, allowing each side of the frame to be unremarkable in and of itself. Tom’s romantic expectation(s) of Summer on the left are entirely consistent with what we’ve seen of their relationship earlier in the movie, and real-life Summer on the right doesn’t ignore or belittle him. What we get is a vision of bland sweetness opposite the sort of friendly awkwardness and moderate avoidance that you’d expect of two people not long out of a failed relationship. Only when Tom sees that Summer has gotten engaged to someone else does the hammer truly fall… at which point the Reality half of the frame pushes the Expectation(s) half (in which Tom and Summer are making out) entirely offscreen. And only one Tom descends the stairs.

Alice Lowe discusses her directorial debut, the horror comedy Prevenge, with

Alice Lowe discusses her directorial debut, the horror comedy Prevenge, with

Universal really is ramping up its new Scarface remake. According to

Universal really is ramping up its new Scarface remake. According to