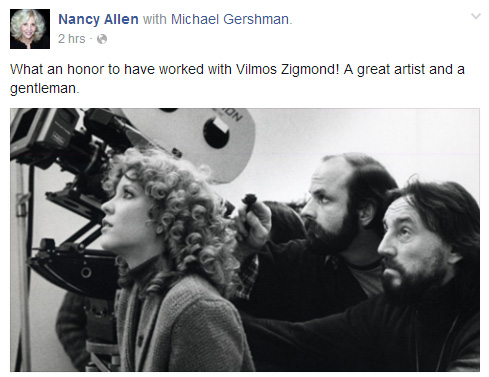

Vulture's Greg Cwik today posted an obituary of Vilmos Zsigmond, who passed away January 1 at the age of 85. In the final paragraph, Cwik gets passionate about The Black Dahlia, and mentions that Zsigmond considered it to be "the last good film he worked on." I'm not sure what the source of that claim is, but here are the concluding two paragraphs from Cwik's article:

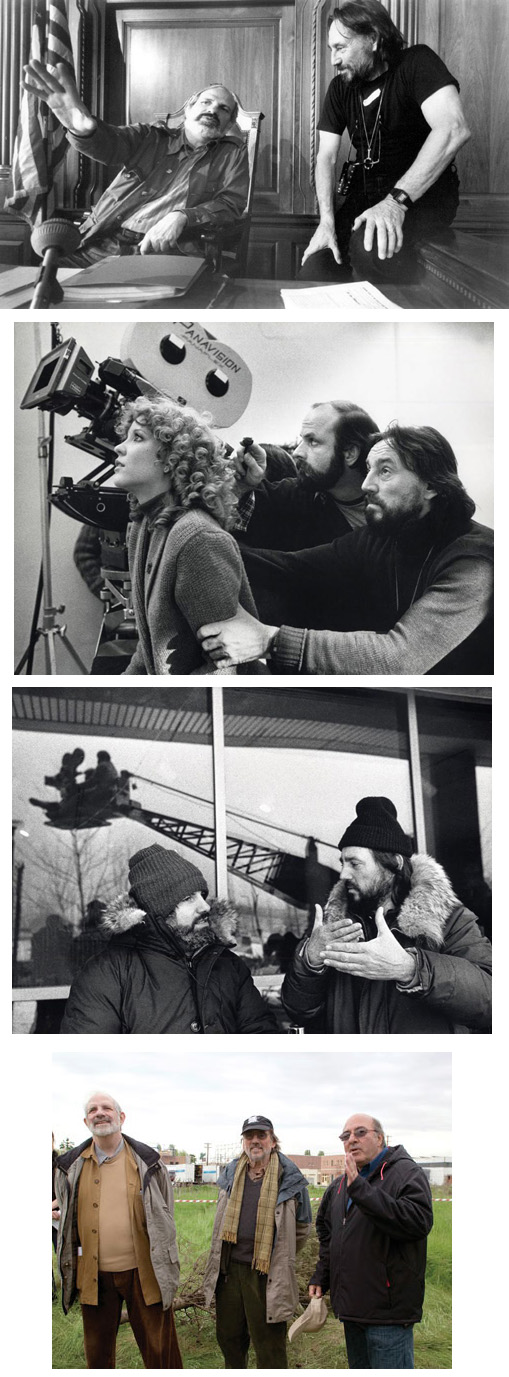

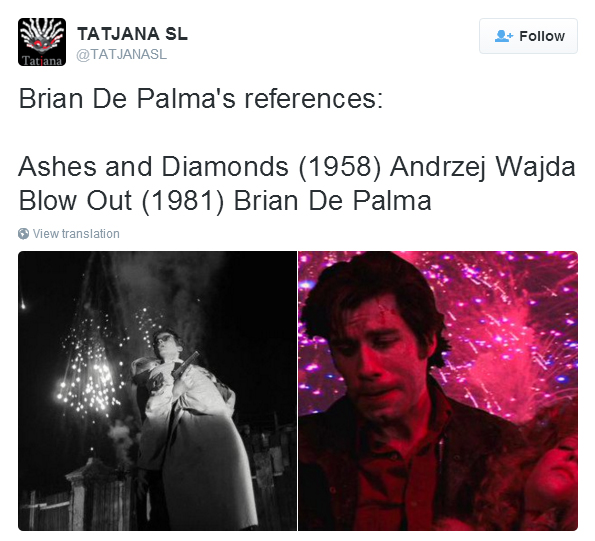

While his work with Spielberg and Cimino is his most acclaimed, Zsigmond’s greatest partner in crime was Brian De Palma, the most purely cinematic filmmaker of the last half-century, for whom the cinematographer did some of his finest, most innovative work. De Palma’s films are not governed by the rules or laws of reality; they adhere to a consistent, internal logic that favors excitement over emotion. Zsigmond extrapolated De Palma’s deep-rooted love for genre and exploitation, and helped the auteur construct his homage-laden films using the visual language written by earlier filmmakers. Together they were like a jazz duo drawing inspiration from their forebears, carving out of pulp scenes of brilliance and brutality. They employed an arsenal of in-camera tricks, from split-diopters to long Steadicam shots and meticulous use of zooms. Zsigmond shot Obsession [(’76)], a fervid Hitchcock homage, and Blow Out (’81), a contender for De Palma’s Best Film. For Blow Out, Zsigmond and De Palma deconstructed the art of filmmaking, reveling in the minutiae of filming and editing and spinning a story of paranoia and murder out of so many reels of celluloid.Zsigmond’s final masterpiece, and one of his most impressive achievements, is also one of De Palma’s most maligned films: The Black Dahlia (’06), which Zsigmond considered the last good film he worked on. A mostly faithful adaptation of James Ellroy's serpentine novel (it retains the terse dialogue while carefully uncoiling the notoriously difficult-to-follow plot), there's nary a shot here that doesn't get the De Palma touch: the camera looms and moves with purpose, zooming in, pulling out, hovering above a dead body splayed on a slab before slowly descending to a low-angle of our heroes framed against effervescent lights, or a crane shot showing the Zoot Suit riots sprawling across streets lined with burning cars and sprinkled with so much broken glass. The narrative is, admittedly, of minimal importance here, as is De Palma's and Zsigmond’s wont; the director fixates on the mood which his DP captured with stunning, sepia-steeped photography. If that isn’t a fine encapsulation of Zsigmond’s endearing legacy, then nothing is.

Updated: Sunday, January 3, 2016 6:49 PM CST

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

Vilmos Zsigmond has passed away. He was 85. According to an initial report by

Vilmos Zsigmond has passed away. He was 85. According to an initial report by