DE PALMA'S 'GREETINGS' AND 'BLOW OUT' INCLUDED IN DISCUSSION

Friday marks the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination. There has been a proliferation of TV specials, magazines, and online articles looking back and examining that weekend of shocking events and images in November 1963. And tonight, Oliver Stone will present a screening of his director's cut of JFK at the St. Louis International Film Festival.

Friday marks the 50th anniversary of the JFK assassination. There has been a proliferation of TV specials, magazines, and online articles looking back and examining that weekend of shocking events and images in November 1963. And tonight, Oliver Stone will present a screening of his director's cut of JFK at the St. Louis International Film Festival.Following the Globe And Mail's "Art of JFK" article from last weekend, which included Brian De Palma's Blow Out as a film which interpolates "themes and events of JFK’s assassination with Ted Kennedy’s 1969 Golgotha at Chappaquidick," three more articles have appeared this week, mentioning certain De Palma films in similar contexts.

The Telegraph's Anne Billson argues that "in the 50 years since John F Kennedy's assassination, the event has been so endlessly repeated on film that it has almost lost its meaning." Billson includes De Palma along with Andy Warhol and John Waters as "early adopters" of JFK iconography on film:

The most famous JFK assassination film, of course, is the home movie taken by Abraham Zapruder (played by Paul Giamatti in Parkland), 8mm footage that has been parsed, recreated and referenced so many times it has attained the status of icon. In turn, it has helped shape the event in the public mind; the film itself wasn't broadcast on network TV till 1975, but frames from it were published, by Life magazine, as early as November 29th 1963. It wasn't the first time an assassination had been caught on camera - footage of the death of Inejiro Asanuma, a chairman of the Japan Socialist Party, was broadcast live on Japanese TV in 1960. But it was the first political assassination to be so thoroughly absorbed, reworked and regurgitated by the cinema.

One of the first artists to co-opt JFK iconography was Andy Warhol, whose Sixteen Jackies depicted serial images of the widowed Jacqueline Kennedy; he also cast some of his The Factory regulars in a never-completed film called Since (1966), a stylised recreation of the assassination in which Gerard Malanga shot Mary Woronov with a banana. "It didn't bother me that much that he was dead," Warhol said. "What bothered me was the way the television and radio were programming everybody to feel so sad. It seemed like no matter how hard you tried, you couldn't get away from the thing."

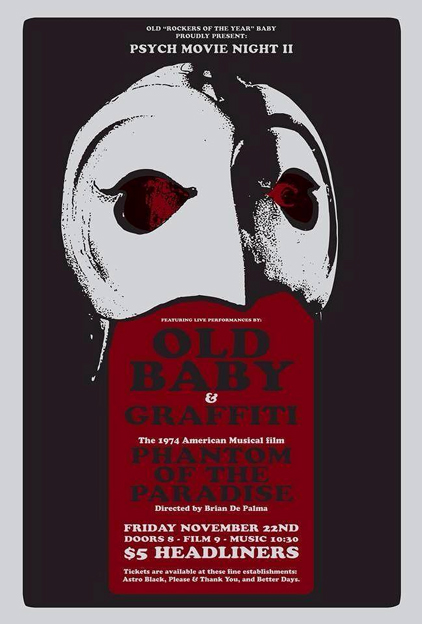

Other early adopters include John Waters, who in 1968 restaged the assassination in his parents' backyard for a 16mm short called Eat Your Makeup, in which Jackie was played by Divine, and Brian De Palma, whose second film, Greetings (1968), satirised JFK conspiracy theorists before most of us were even aware they existed.

The Wall Street Journal's Richard B. Woodward echoes Billson when he writes, "Countless repetitions of anything can convert even tragedy into farce and rewire our original emotional responses in myriad other ways." His article focuses on how the "photo of Lee Harvey Oswald's killing became primal artistic material." In one section, Woodward looks briefly at the impact the Zapruder film had on other movies, where he notes several film, including Blow Out:

The impact of the Zapruder film, especially on other movies, was quickly apparent. Its spooky dynamics shaped Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow Up (1966), in which a photographer in a park may have unintentionally documented a murder. Scenes where he studies his contact sheets with a magnifying glass, looking for bodies in the bushes, anticipate what was soon standard practice for amateur sleuths analyzing the 486 frames in Zapruder's film in hopes of debunking the Warren Commission Report. According to Mark Harris's book Pictures at a Revolution, the sickening frames 313-14 of the president's skull exploding influenced the graphic, slow-motion shootings at the end of Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974) and Brian De Palma's Blow Out (1981) picked up the theme of technology inadvertently detecting a crime. In both cases, a sound recording finds evidence of a murder, actions that, when discovered by the murderer, put a bull's eye on the sound recorder, too.

The most interesting part of Woodward's article comes when he discusses Coppola's first two Godfather films:

But perhaps no movie or novel so internalized the twin killings in Dallas as the first two films in The Godfather trilogy. Riddled with allusions to the Kennedys, the films adopted images of that weekend to tell a larger story about American power and corruption. Many Americans suspected then—and believe now—that the Mafia was involved in some unholy fashion in either Kennedy's or Oswald's death, or maybe in both.

The climax of The Godfather (1972), in which Michael Corleone attends the church baptism of his nephew while his enemies are being executed around the country, has striking similarities to images on TV screens during the morning of Nov. 24, 1963. Mr. Coppola's cross-cutting is not unlike what many American families saw that Sunday when religious proceedings were interrupted by the shocking sight of Oswald being gunned down by Ruby.

A classic exchange late in The Godfather: Part II (1974) between Michael and Tom Hagen, the Corleones' lawyer, unmistakably connects Kennedy's death to Oswald's.

As Michael calls for the execution of Hyman Roth, their crafty rival who is being deported back to the U.S., Tom objects that such a plan has no chance of succeeding.

"It's like trying to kill the president," he says. "There's no way we can get to him."

"Tom, you know you surprise me," answers Michael with chilly authority.

"If anything in this life is certain, if history has taught us anything, it's that you can kill anyone."

Mr. Coppola confirms this cynical truth by directing the assassination of Roth to resemble the shooting of Oswald. As Roth speaks to the press after landing at Miami airport, Corleone henchman Rocco Lampone, posing as a reporter with notebook in hand, pulls out his gun and kills Roth, before being shot himself by police.

Metro U.S. New York's Matt Prigge provides a very interesting list of movies centered around the JFK tragedy. Here's what Prigge writes about Waters' Eat Your Makeup and De Palma's Greetings:

Eat Your Makeup (1968)

South Park once claimed it took 22.3 years for terrible things (in their case, AIDS) to be funny. But it only took five years for no-budget filmmaker John Waters to, in his first film, recreate the assassination in his parents’ backyard, complete with Divine as Jacqueline Kennedy.

Greetings (1968)

1968 was also the year it started being funny to mock JFK conspiracy theorists. Brian De Palma’s first of two episodic comedies with a young (and then mustachioed) Robert De Niro features a guy (Gerrit Graham) who bores people with his claims of a massive coverup.

Updated: Friday, November 22, 2013 12:29 AM CST

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Emily Mortimer, who has already been cast as the lead in Brian De Palma's upcoming

Emily Mortimer, who has already been cast as the lead in Brian De Palma's upcoming

Neil Mitchell has written a new book about Brian De Palma's Carrie, as part of the "Devil's Advocates" series from Auteur Publishing. The book was released in the U.K. last month, and should be available in the U.S. early next year.

Neil Mitchell has written a new book about Brian De Palma's Carrie, as part of the "Devil's Advocates" series from Auteur Publishing. The book was released in the U.K. last month, and should be available in the U.S. early next year.

Brian De Palma's Passion will screen three times as part of the 27th edition of the

Brian De Palma's Passion will screen three times as part of the 27th edition of the