Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | August 2013 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Cine Vue's John Bleasdale interviewed Brian De Palma at the Venice Film Festival last September, and posted the article today, as Passion is released on DVD and VOD in the U.K. and Ireland. Back when talking about Passion was still quite fresh for him, De Palma compared it to The Women (a film he mentioned briefly in a more recent interview), and also answered a question about the giallo genre his films are often compared with. De Palma tells Bleasdale that with Passion, "I set out to make what I thought was a clever mystery even cleverer. Redacted is completely driven by men and so making this we're doing the opposite. It's a bunch of conniving business women who are passionately entwined, and it's like George Cukor's The Women. It's all these women manoeuvring."

Cine Vue's John Bleasdale interviewed Brian De Palma at the Venice Film Festival last September, and posted the article today, as Passion is released on DVD and VOD in the U.K. and Ireland. Back when talking about Passion was still quite fresh for him, De Palma compared it to The Women (a film he mentioned briefly in a more recent interview), and also answered a question about the giallo genre his films are often compared with. De Palma tells Bleasdale that with Passion, "I set out to make what I thought was a clever mystery even cleverer. Redacted is completely driven by men and so making this we're doing the opposite. It's a bunch of conniving business women who are passionately entwined, and it's like George Cukor's The Women. It's all these women manoeuvring.""I SHOULD HAVE BEEN A SILENT MOVIE DIRECTOR"

Bleasdale brings up the split screen sequence in Passion, which leads De Palma to discuss his love of silent pictures. "In my whole career, I've been fascinated by long, silent periods which are punctuated and scored by music. I should have been a silent movie director. I just love that form. And I'm probably one of the few directors who's still practising it. Whenever I do a sequence in a film everyone says 'Yikes! What's that?' Why isn't everybody talking all the time. Everybody is brought up on television. All you have is heads talking to each other. It's very easy to shoot - a close-up here, a close-up there - but for me this is boredom. We have a big visual screen here, we can do all kinds of things with the camera, so I try to find material which lends itself to that."

De Palma also talks to Beasdale about how screens are getting smaller and smaller, how the "big spectacular movies" on IMAX are basically kids movies, and how at 71 years of age, Marvel superheroes don't interest him anymore. When asked if he worries about the future of serious cinema, De Palma replies, "No, because there's a whole independent cinema. It's cheaper to make movies. You can make a film with your high definition camera and edit them on your Mac, so you can make personal movies that cost nothing. Whether you write a novel or paint a painting, it's always difficult to get anyone to look at it." The interview concludes with De Palma contrasting his early days working for studios with today: "When you're making a big studio picture there are a lot of meetings and you're getting a stack of notes on your script. I grew up in the era when the director was the superstar and said, 'Fuck you, take your notes and throw them out the window.' And we got away with it for a while."

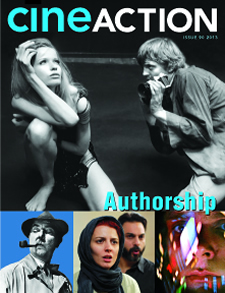

Issue 90 of Cineaction, available now, carries the theme of authorship. To that end, David Greven has written a terrific essay about Brian De Palma's Obsession for the issue. Titled, "De Palma's Vertigo," Greven starts out by stating that he thinks Obsession "is one of De Palma's finest" films. Greven suggests that instead of playing down the ties to Hitchcock in De Palma's work, as is the tendency of De Palma's supporters, "we should do the opposite." Throughout the article, Greven notes echoes of Hitchcock in Obsession, from, obviously, Vertigo, but also from Rebecca, Notorious, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Psycho, Dial M For Murder, Suspicion, and Marnie.

Issue 90 of Cineaction, available now, carries the theme of authorship. To that end, David Greven has written a terrific essay about Brian De Palma's Obsession for the issue. Titled, "De Palma's Vertigo," Greven starts out by stating that he thinks Obsession "is one of De Palma's finest" films. Greven suggests that instead of playing down the ties to Hitchcock in De Palma's work, as is the tendency of De Palma's supporters, "we should do the opposite." Throughout the article, Greven notes echoes of Hitchcock in Obsession, from, obviously, Vertigo, but also from Rebecca, Notorious, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Psycho, Dial M For Murder, Suspicion, and Marnie."A telling example of the film's detached position toward Courtland is the brilliant pure-cinema sequence in which he makes the drop-off of the fake ransom money, as a French-accented detective urges him to do, during the first kidnapping. Herrmann's score charges the entire sequence with grandiloquent portentousness. As he journeys on the ferry the 'Cotton Blossom' (which evokes images of the Old South), its huge red wheel churning in the water like the tragic gears of fate, Courtland, in dark sunglasses and dark suit, macabrely tapping his wedding-ringed finger on the black suitcase full of blank paper, seems more like the villain, a coldly impassive hired assassin on his way to a hit. If the sequence can be read as a critique of normative masculinity, an entirely incongruous but also richly symbolic detail reinforces this critique. A troupe of Boy Scouts scamper aboard the Cotton Blossom as it departs. We pull back to see, from a distance, the stoic, impassive, opaque image of Courtland standing on the deck as the Scouts board the ship. Later, after Courtland has hurled the suitcase on the wooden planks of the drop-off point, we see only the ghostly shadows of the Scouts. Here is the payoff of the Boy Scout motif, an eerie dream-image of boyhood and lost promise, suggesting that adult masculinity derives from a corruption of a former state of innocence. Even stranger is the shot of Courtland after he has dropped off the money, standing alone in a passageway, dark sunglasses and dark suit intensifying his dark-haired appearance, as the brown waters beneath the ferry churn. Discordantly, this shot further conveys the sense that he is a dubious, even frightening figure, far from the sympathetic male lead on the verge of losing everything."

The Skinny's Paul Houghton from the U.K. posted an article about Brian De Palma yesterday. In discussing Passion, De Palma tells Houghton, "I've always been controversial. I’m not like my peers that went to Hollywood in the 70s. They became the establishment, but I’m not liked in certain quarters of the industry because I’ve always tried to do things on my own terms. I see myself as an outsider."

The Skinny's Paul Houghton from the U.K. posted an article about Brian De Palma yesterday. In discussing Passion, De Palma tells Houghton, "I've always been controversial. I’m not like my peers that went to Hollywood in the 70s. They became the establishment, but I’m not liked in certain quarters of the industry because I’ve always tried to do things on my own terms. I see myself as an outsider."It’s a marked decline for a director who deserves to be considered an A-lister. Years before Martin Scorsese was on the scene, De Palma was giving Robert De Niro his breaks on the streets of New York with anti-Vietnam films Greetings and Hi Mom!, and comedy of errors The Wedding Party. In the mid-70s, he handed Scorsese the Taxi Driver script. In his first Hollywood gig, Get to Know Your Rabbit, De Palma directed Orson Welles. He was the man George Lucas turned to when he got stuck on the Star Wars "A long time ago…” prologue. He was selected by Tom Cruise to kickstart the Mission: Impossible franchise, creating the iconic image of Cruise hanging suspended above a neon-white, touch-sensitive room, a bead of sweat hanging from his glasses. Now he’s pinning his hopes on the whims of iTunes, Sky Box Office and Tescos.

It seems a strange decision, but Metrodome have crunched their numbers. De Palma, though, is sanguine about the release: “I made this film, as I’ve made all my films, to be seen on the big screen,” he says. “But I’m in my seventies now, and I see my daughter watching most of her films on her laptop. Technology will continue to change everything, so what are we going to do about it? Anyway, the cinema to me seems more about pre-sold franchises, and that has absolutely no interest to me whatsoever.”

This isn’t the first De Palma film to scale the murkier depths of British film releasing. Femme Fatale never saw the inside of a British cinema while Redacted, [2007]’s deeply controversial “fictional documentary” about human rights abuses – on both sides – of the Iraq war, got a brief and limited theatrical run before disappearing from view. “Redacted did something that no film has ever done; it criticised the American troops,” he says. “That’s unheard of in America. You just can’t question the boys. But the film came from stories soldiers were sharing of their experiences and posting online. I still find it gob-smacking – disgusting –that we tried to claim victory in that country.”

Redacted, he concedes, may have impacted on his ability to find funding for his films. But he doesn’t regret making the film, seeing it as a return to his formative years. The young De Palma consciously positioned himself as “America’s Godard,” spending the 60s independently making angry liberal firebrand films on the East Coast before Hollywood called as he hit 30. It is, he says, the great failing of the generation of filmmakers that will follow him: “I’m confounded by the lack of political films out there by young directors. The corruption that exists in the circles of power, be it in Washington or Hollywood, remain industrial. It hasn’t changed since I was young. But where are the political filmmakers? Where’s the outrage? The public relations people are in control of the media now.”

Bullett Media's Joshua Sperling asked Brian De Palma to discuss "5 of his most unforgettable films." Of course, one of the five is his newest, Passion, still pretty unforgettable. However, the most interesting portion of the article has De Palma talking about his adaptation of Tom Wolfe's The Bonfire Of The Vanities, which De Palma had originally defended, but then in more recent years, seemed to have conceded to having made some mistakes with the film by altering the source novel. Now, more than 20 years after its release, De Palma tells Sperling that he finds his film successful, after all. Sperling himself states that Bonfire "now ranks as one of De Palma’s most underrated and exuberant studies of the absurd theater of American politics."

Bullett Media's Joshua Sperling asked Brian De Palma to discuss "5 of his most unforgettable films." Of course, one of the five is his newest, Passion, still pretty unforgettable. However, the most interesting portion of the article has De Palma talking about his adaptation of Tom Wolfe's The Bonfire Of The Vanities, which De Palma had originally defended, but then in more recent years, seemed to have conceded to having made some mistakes with the film by altering the source novel. Now, more than 20 years after its release, De Palma tells Sperling that he finds his film successful, after all. Sperling himself states that Bonfire "now ranks as one of De Palma’s most underrated and exuberant studies of the absurd theater of American politics."M:I - "IT'S EXCITING TO HAVE A BLOCKBUSTER"

Another film discussed is Mission: Impossible. "This was the first film Tom [Cruise] ever produced," De Palma tells Sperling. "Because I’d produced a couple of pictures at that point, he and his partner Paula [Wagner] at times relied on my judgment. I remember that Tom was very responsive and straightforward. There were two very difficult scenes in the film: the CIA vault scene and the one atop the train. We had a jet engine creating the wind for the train sequence. You couldn’t stand up without being blown off. The shot where Tom does the flip, that’s really dangerous stuff for anyone to do. He did it twice for us, which was very brave. We were on top of that train for weeks and weeks. As for the CIA vault, that was my idea. I’d wanted to do an incredible action sequence that was completely silent. And then I had to think of all the things that could go wrong as the character tried to lower himself upside-down into this mythic vault. It was a sequence I thought about for months and months before I actually filmed it. Whatever people say, it’s always exciting to have a blockbuster. Everybody thinks you’re a genius for 30 seconds."

THE MEGALOMANIA OF AMERICAN SOCIETY

De Palma also talks about Carrie and Scarface. Of the latter, he tells Sperling, "Some people say this film is excessive—I disagree. The script was a direct report by Oliver [Stone] on the places he visited in Miami. He saw all the clubs, the coke on the tables. People were cutting each other up with chainsaws! We had a battle with the MPAA because they wanted to give it an X rating. We even had narcotics cops from Florida come to testify that people should see this film because it showed what was actually happening. On a deeper, thematic level, Scarface is about something that recurs in a lot of my films: the megalomania of American society that can lead to excessiveness, greed, and very cruel interplays between people who are desperate to stay on top. Wealth and power isolates you. Whether you’re Walt Disney or Hugh Hefner, you create a bubble around yourself. It’s that old cliché: power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Pacino conveyed that perfectly. He kept his Cuban accent, on- and off-set. His sidekick in the film, Steven Bauer, was Cuban, so they were constantly speaking in that accent during the shoot. There are a lot of quotable moments in the film but my favorite is, ‘Every day above ground is a good day.’"

At left is Metrodome's cover for the U.K. DVD edition of Brian De Palma's Passion. Ferdy On Films' Roderick Heath posted a review of the film this week-- here are some highlights from his review (SPOILERS might occur):

At left is Metrodome's cover for the U.K. DVD edition of Brian De Palma's Passion. Ferdy On Films' Roderick Heath posted a review of the film this week-- here are some highlights from his review (SPOILERS might occur):...

"The main problems of Passion stem from its translation of Corneau’s film and De Palma’s half-hearted annexation of its actual storyline. Whereas the original offered a certain sly, dark humour and obliquely considered consequence in its resolution, De Palma deconstructs everything to the point where suspense and empathy are essentially rendered unimportant: Christine, Isabelle, Dirk, and Dani are all pretty loathsome, whilst the representatives of the law, a bullying prosecutor (Benjamin Sadler) and stern cop (Rainer Bock) who becomes smitten with Isabelle, are, ironically, increasingly castrated. [Noomi] Rapace feels faintly miscast as a victimised fawn with a neurotic psycho under the surface, though that might be a result of associating her too much with her canonical role. [Rachel] McAdams, on the other hand, seems best in key with the film’s sly-malicious tune, particularly when Christine tries to bully Dani by setting her up on a sexual assault charge, an apex of campy humour. De Palma loves reiterating that his characters and their plights are all inventions, variations on themes that can be suddenly turned in upon themselves, revised, sent into rewind, or erased altogether, usually with some moment of choice from which guilt or complicity, a nexus of consequence both for good and evil, is identified."

TWO SEQUENCES STAND AMONG DE PALMA'S BEST

The Dissolve's Noel Murray feels that "for the first half-hour or so, Passion feels lackadaisical, with Rapace and McAdams coming off as awfully stiff. Then, right around the time Isabelle makes a bolder play for recognition—and is countered by an even more ruthless move from Christine—De Palma wakes up. After a hilariously over-the-top music cue by composer (and frequent De Palma collaborator) Pino Donaggio, the movie’s pace quickens and its style becomes more expressionistic, with longer shadows and more extreme angles. Before Passion ends, De Palma comes through with two sequences (neither of which originated with Love Crime) that can stand among his best: one where Christine is stalked on half a split-screen while the other half shows a fourth-wall-breaking performance of The Afternoon Of A Faun, and another that wordlessly sends four characters in pursuit of each other inside and outside Isabelle’s apartment."

Murray concludes his review by noting De Palma's focus on the visual: "With Passion, De Palma is on more familiar ground, using the world of the erotic thriller to note how Skyping, sexting, and tiny pocket cameras are changing behavior, putting everyone in the spotlight and distracting the eye. That’s ultimately what makes Passion a more effective film than the one it’s remaking. While Corneau and Carter were telling a story about what their characters do and don’t see, De Palma is more engaged with what the audience sees. There’s always something to look at in the background of Passion, from the erotic paintings on the walls of Christine’s flat to the video billboards posted around Berlin, and always something eye-catching in what the characters wear, or how they’re posed. The movie is one long game of misdirection, playing tricks on viewers from scene to scene, and showing how easy it is to steer a crowd into missing something important. That’s the real De Palma touch, even more than the operatic overtones and excess."

Back in early 2009, I posted links to a couple of reviews of Erik Van Looy's Loft, in which five married men share a penthouse loft where they indulge in their various affairs. The dead body of an unknown woman is discovered in the loft, and paranoia among the men ensues. Variety's Boyd Van Hoeij wrote that the film features "a nod to Brian De Palma in a standout sequence at a casino." FilmFreak's Alex De Rouck mentions that Van Looy and screenwriter Bart De Pauw emphatically wink to De Palma "in his Hitchcock period (especially in the long scenes in Dusseldorf and in the casino)."

Back in early 2009, I posted links to a couple of reviews of Erik Van Looy's Loft, in which five married men share a penthouse loft where they indulge in their various affairs. The dead body of an unknown woman is discovered in the loft, and paranoia among the men ensues. Variety's Boyd Van Hoeij wrote that the film features "a nod to Brian De Palma in a standout sequence at a casino." FilmFreak's Alex De Rouck mentions that Van Looy and screenwriter Bart De Pauw emphatically wink to De Palma "in his Hitchcock period (especially in the long scenes in Dusseldorf and in the casino)."

Sorry for the late notice on these, but last Friday, three new interviews with Brian De Palma popped up on the web. Here are some highlights (THERE MIGHT BE SOME SPOILERS!):

Sorry for the late notice on these, but last Friday, three new interviews with Brian De Palma popped up on the web. Here are some highlights (THERE MIGHT BE SOME SPOILERS!):I don’t really think about that. It’s a lot of problem solving. You take from the original film, which you like, and when you say, “Well I can’t reveal the murderer’s identity when this character is killed, unlike the original film. So, I’m not gonna show that. Well, where is she? In the original film, she’s in the movie theater. In this, I put her in the ballet because that’s something that I always wanted to put in a film. I wanted to juxtapose the ballet with the murder, but that’ll evolve. And I was fortunate enough to find a very talented ballerina who had done the ballet in Germany and we were able to get the rights to reproduce it in our movie. All these things sort of make the movie and I could use this split screen idea to make the audience think that Noomi is at the ballet by using that trick and ultimately revealing that she’s not at the ballet, but she’s really under the scaffolding by Christine’s house.

I love when you use split screens. It’s one of my favorite things you do in your films. The way you use it to tell a story is fascinating. Have you always liked using that, especially in a film like this?

Well, it’s a technique, one that’s very effective. I tried to use it in Carrie to show the destruction of the prom, but something that I realized is that it’s not good for action. Split screen is not good for action and I consequently used very little of it. When we looked at it, I said, “This is not working.” So, I removed a lot of split screen from that sequence, but it’s kind of a meditative form. A kind of form to show a lot of juxtaposition and it’s a slow form. It’s a form that you have to allow to really sink in and it worked quite well in this movie. Using the ballet as this sensuous act between these two dancers and, kind of like a magic trick, you’re looking at one side of the screen when something really sinister is going on on the other side. When you can catch an audience off guard a little bit, that’s quite good.

...

I like the fact that in your work you still focus on the slow burn and it seems like a lot of filmmakers today don’t do that. They want to keep the action going. Do you ever feel like you need to move on and just do a film with quick cuts and all that?

No, I think that’d be a big mistake. After seeing these big action films, it feels like an endless drumming. After a while, everyone says, “Please, stop! I can’t take this anymore!” The sequences are too long, they’re not carefully thought out and with all choreography and in all action sequences you have to have a slow build up in order to go fast. You need to be quiet in order to be loud. That’s sort of a basic thing in all art forms, whether it be music or film.

[This interview also has a lot of De Palma quoting Rachel's lines from the film and laughing about them, etc.]

De Palma: Are you really a film school reject?

I actually couldn’t afford to go to film school.

I am a film school reject! I took a two semester course at NYU. The teacher and Martin Scorsese were so unhappy with my movie. The problem was I shot it in three days, but it was supposed to be done in eight weeks. He took my whole unit off my movie and put them on another movie, leaving me alone in the editing room. They never liked me at NYU. Well, I am a film school reject, so I can identify with your site [Laughs].

Why didn’t they like you at NYU?

You know, if you haven’t been to film school, you shoot 100 feet of film, people talk about it, you shoot another 100 feet of film, and everyone talks about it. I shot all my film on a weekend. I wasn’t interested in what they had to say about my 100 feet of film. That was the end of my film school experience. Later on I taught, so I went to the other side of it.

Would you recommend film school?

Yeah. When I was in graduate school I had a very good theater teacher where I learned a lot. I’d absolutely recommend it.

...

When do you know what the visual language of a film is going to be? When writing the script for Passion, do you know exactly how the camera should move and the aesthetic you want?

Well, at the beginning of the movie, you’re basically dealing with girls talking to girls across a desk, so you have to find an interesting location to put all that. I found a fantastic office building in Berlin. When you get into what Isabelle is dreaming and what actually happened and what didn’t, then you get a chance to really pull out all the stops and make it very visually evocative. Of course, I love to do stuff like that.

Over the past few years, from The Black Dahlia to Mission to Mars, you’ve taken on notable challenges. At this point, is it still easy to find challenges?

Every film has its challenges. As long as you have ideas and ways to solve them that are interesting to your particular aesthetic, it’s great fun to do. This film had a great opportunity because it’s all women, and I love shooting women.

Even the German girl who played Dani was another fabulous actress. She had a very difficult part because she was acting for her first time in English and she had all that complicated exposition. I mean, with “Dani the explainer” in that kitchen scene, her job is to make that interesting. That was quite a feat she managed.

She has a such a distinct look as well.

Yeah, she was in Perfume as well. I’m a friend of Tom Tykwer’s. When I saw that red hair in Perfume, I thought, “That’s what we want!” I wanted red, but not that red [Laughs]. I love that film.

Same here. There are a few filmmakers from your generation that have kind of lost their touch. What’s the trick in maintaing that initial spark?

You mean, how have I not become a fossil?

Exactly.

Thanks. How do I answer that? Well, with fame and success, people tend to insulate themselves. I tend to still be very much the film student, basically. I’m the only director that goes to film festivals just to see movies. I’ve been saying this for 30 or 40 years, but nobody seems to have caught on. When I go to a film festival they ask, “What are you doing here? Do you have a movie coming out?” “Well, no.” “Then what are you doing here?” I say, “I’m here to look at the movies!”

I don’t have bodyguards or an entourage. I go to the movies like if you were at a film festival. Also, I hangout with a bunch of young directors. I miss the fraternity we had in the 1970s, because all my friends from then are in different parts of the country. I hang out with directors who live in my neighborhood. That keeps you lively. What can I say?

The Dissolve: One of the more compelling aspects of the movie is its office setting, which is this transparent space where people also have hidden agendas. What were you looking to get out of that design?

De Palma: That’s an extraordinary building in Berlin. The whole building was vacant because of the recession. So we were very fortunate to get in there. And it’s a beautifully designed home for these aggressive advertising executives. I scouted many buildings, and we were very fortunate to get that particular one, because the schedules changed, and sometimes the buildings weren’t available. A lot of things happen in movies by happenstance, and you adjust your material to that.

The Dissolve: When you were scouting buildings, this was the type of space you were looking for?

De Palma: An office is an office. There’s a table, and somebody’s on one side of the desk and somebody’s on the other. And there are a lot of scenes like that in the film, so the more interesting space that you could put them in, the happier I am.

...

The Dissolve: Your work is carefully orchestrated, but where does the planning stop? Are there areas of the production that you like to leave open?

De Palma: This is a relationship picture, and the girls came in to rehearse, and we sort of watched what they did and how they played with the material, and we adjusted the script to their interaction. But in terms of the long, silent sequences, the dream sequences… That’s pretty carefully laid out. I had a lot of time to basically storyboard the whole movie.

The Dissolve: Does it frustrate you as a filmgoer to see the language of a film employed less carefully than that? All that work is elided in a lot of movies.

De Palma: Yes, I would agree. I’m astounded by—whether you’re making a science-fiction movie, a zombie movie, a Star Trek, a Marvel Comics Spider-Man movie—these action sequences that seemingly go on endlessly, without any type of shape or form. So much in action has to do with choreography, and orienting the viewer in where everything is. And I’m amazed all the time that nobody seems to pay much attention to that. So you basically get action and reaction, and it’s like an endless drumming without any shape.

The Dissolve: It seems like they’re trying to make up in sheer, visceral force things that could be done much more elegantly.

De Palma: And obviously, in order to have a crescendo, you have to have some silence. It’s just so simple, but nobody seems to pay much attention to it. They’re basically banging at you constantly. And then in a movie, it’s two hours, too, and then everybody says, “My God, when is this going to be over?” [Laughs.]

The Dissolve: Passion includes a really big split-screen sequence. What was the planning like for that, and what effect were you were looking to achieve?

De Palma: I always wanted to use that ballet. I saw it on video on the Internet. It was shot in the ’50s somewhere with Jerome Robbins’ choreography of Afternoon Of A Faun. And it’s a fantastic idea: ballet dancers in a rehearsal room going through their motions, relating to the mirror, and then obviously culminating in the kiss at the end. And I’ve always wanted to use this piece. I just think it’s so beautiful, and so cinematic. So I had the opportunity to put it into this film. The original movie had Isabelle going to the movies and slipping out the side door, and I put her at the ballet. And I used that tight close-up to make the audience think she was always at the ballet while the murder was going on at the house.

[Regarding the score for Passion, De Palma said:]

I’d say the toughest thing we had to figure out was the scene where Noomi suffers that humiliation and walks down from her office to the garage. We had to figure out how to not make it too sentimental, and at the same time deal with the fact that she’s been demolished. So that was very tricky. We spent quite a lot of time trying to get the exact right cue.