REVIEWS FOR 'MR. SCORSESE' - EXCERPTS

REBECCA MILLER'S 5-PART DOCUSERIES PREMIERES ON APPLE+ OCT 17

Reviews for

Rebecca Miller's

Mr. Scorsese have begun to appear today - here are some excerpts:

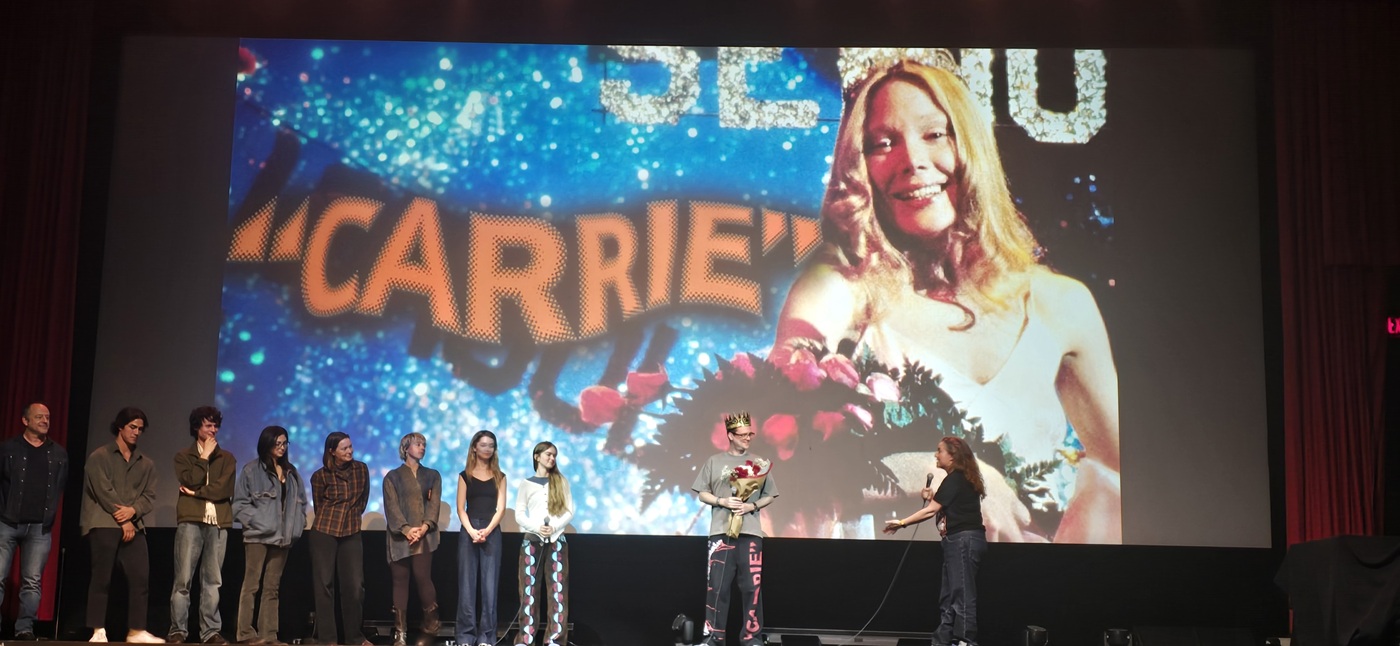

Daniel Fienberg, The Hollywood Reporter

For the most part, Miller has access to all of the people you need to tell Scorsese’s story — starting with Scorsese, who clearly sat for a lot of in-depth interviews in a variety of locations, including what appears to be a waterside vacation house; a cluttered urban office; and, best of all, several darkly lit restaurants, where he gets to gab with friends from childhood as they remember their rough-and-tumble upbringing with a mixture of candor and nostalgic romanticization. Miller sits down with all three of Scorsese’s daughters, ex-wife Isabella Rossellini, peers like Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg, stars such as De Niro and DiCaprio (along with the likes of Miller’s husband Daniel Day-Lewis, Margot Robbie and Sharon Stone), and an assortment of regular collaborators, with longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker and writing partners like Paul Schrader and Jay Cocks among key behind-the-scenes figures. Rounding out the documentary are younger directors following to varying degrees in Scorsese’s footsteps, like Spike Lee, Ari Aster and both Safdie brothers. Journalist/film scholar Mark Harris pops up late in the series to smooth some intellectual transitions. These relative outsiders offer some insight, but rarely feel as seamlessly integrated into Miller’s story as the people who were there.

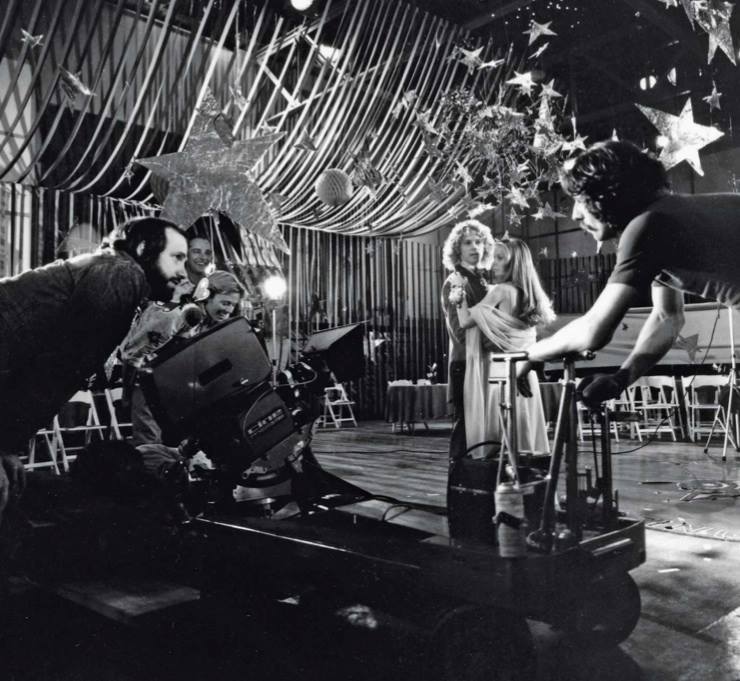

The first two episodes, which lay the foundation for all of Scorsese’s fixations and themes, were my favorites, with Scorsese and his assortment of matured tough-guy pals steering anecdotes interspersed with storyboards drawn by a young Scorsese and footage from his acclaimed student films. Miller is never formally adventurous, though some of the art/artist parallels are illustrated in thoughtful split-screens. From the violence he witnessed in the streets to the escape offered by secure and air-conditioned movie theaters to the moral inquiry prompted by his immersion in Catholicism, this is Scorsese in a nutshell, delivered with the director’s trademark volubility that remains delightful even if most of the background was conveyed in documentaries like Italianamerican and A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies.

Martin Scorsese has always been an open book, a storyteller who has offered his autobiography freely and an auteur whose deepest philosophical themes have been recurring and explored in bold type. That he’s never been an “Oh, I’d prefer to let the work speak for itself” recluse is to Miller’s advantage. But she has to push to get different or deeper engagement, leaving many of her questions and conversational detours audible.

Ben Travers, IndieWireIn the second episode of Rebecca Miller‘s enthralling five-part documentary on Martin Scorsese, the chronological review of his life and career reaches the 1976 classic “Taxi Driver.” Jodie Foster, sitting for a new interview on a film she’s been discussing for almost five decades, recounts how “gleeful” her director was to be making movies. “He was excited about how the blood got made,” Foster says, her eyes widening to mimic Scorsese’s delight. “And, when he was gonna blow the guy’s head off, how they put little pieces of Styrofoam in the blood so it would attach to the wall and stick there.” “We had a great time,” Scorsese says. But then he pivots. He starts talking about how the studio “got very angry at us because of the violence,” because of the language, because of the “disturbing” depiction of New York City’s “seedy” underbelly. When the MPAA slapped “Taxi Driver” with an X-rating, Columbia Pictures told Scorsese to edit it down to an R-rating — or they would.

“That’s when I lost it,” Scorsese says. Miller pipes in to ask what he did, exactly, and Scorsese — visibly irked by the memory — repeats himself, stammers a bit, and then breaks into a wide grin. He knows the story from there, but the documentary allows Steven Spielberg (who Scorsese called for advice at the time) and Brian De Palma (who remembers Scorsese “going crazy”) to set up what happens next. All Scorsese has to explain is whether he had a gun (he says he didn’t) and why he was “going to get one.” “I would go in, find out where the rough cut is, break the windows, and take it away,” he says. “They were gonna destroy the film anyway, you know? So let me destroy it.”

Thankfully, it never came to that, but the director’s two extremes — the divine joy Scorsese finds through making movies set against the near-total ruination he’s endured for his art — rest at the center of what Miller aptly designates “a film portrait.” While touching upon all his feature films (almost), including new interviews from famous collaborators like Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio, as well as childhood friends and family members (including his three daughters), the series juxtaposes the angels and demons that have long defined one of cinema’s true “cornerstones” (as Spielberg calls him) in order to better appreciate how he’s interrogated them, year after year, right in front of our eyes.

Yet for as heavy as “Mr. Scorsese” can get — addressing modern America’s scourge of Travis Bickles, the rise of the religious right (timed to “The Last Temptation of Christ”), and Scorsese’s brush with death, four divorces, and bout with depression — it’s also enormously entertaining. Miller launches right into her invigorating assessment and keeps the pace up throughout.

Matt Goldberg, The WrapSince the docuseries largely spends its time exploring Scorsese through his features with occasional offshoots regarding his personal life (his marriages, his celebrity, etc.), “Mr. Scorsese” is mostly successful at recontextualizing the filmmaker before he became a legend. We can see that for decades, Scorsese, despite his acclaim, always had a tumultuous relationship with Hollywood, a town that didn’t always know what to do with someone who never had the populist touch of contemporaries like Spielberg or even De Palma. His violence was deemed too aggressive and his movies were unafraid of ambiguous conclusions. That was never going to fit into a post-70s Hollywood, and it’s fascinating to see movies like “The Color of Money” and “After Hours” as a way of Scorsese fighting his way back in only to invite controversy once again with “The Last Temptation of Christ.” As the docuseries moves into its fourth episode, you can see what Miller is up against as each Scorsese movie or project could conceivably be worthy of its own documentary. “Mr. Scorsese” sets “Last Temptation” up to be a major battle and turning point, but it’s resolved in about five minutes so the episode can get to “Goodfellas,” which is understandably a bigger and more influential work in Scorsese’s oeuvre. Once the series reaches the ‘90s, it feels like it’s on fast-forward a bit, trying to get to all of the director’s narrative features even if only for a minute (there’s hardly any time spent on “Cape Fear” or “Bringing Out the Dead” and “Hugo” gets skipped entirely), and starts to miss what makes Scorsese a transcendent force worthy of a five-episode docuseries.

Consider that other directors receive this kind of glowing documentary treatment (the series is dubbed a “film portrait,” which I feel is accurate), but even Spielberg and De Palma only got features. Scorsese is worth this long-form exploration, but not because he’s made so many movies or lived such a rich life. The biggest element that Miller opts to largely omit is his contribution to cinema as an artform beyond himself. We all know that Scorsese has made so many incredible movies, and credit to “Mr. Scorsese” for likely leading viewers to check-out some of his less-appreciated work like “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore” and”Age of Innocence.” But to only include about a minute or so on The Film Foundation and the World Cinema Project in the docuseries’ final 20 minutes feels like misunderstanding why Scorsese is a unique force in film history.

Miller fully grasps Scorsese’s ongoing outsider status (after watching this, I now have no problem understanding why it took until “The Departed” for him to win Best Director and why “Killers of the Flower Moon” received 10 Oscar nominations and zero wins), but what elevates him as a rare figure are his larger contributions to restoring and supporting the art of cinema. I can understand not making time for his TV work like “Vinyl” and even skipping his music documentaries outside of “The Last Waltz.” But Scorsese, unlike almost any other major filmmaker, has used his power and influence to uplift cinema as an artform. No other mainstream director spends their time trying to figure out how to restore a movie like “Touki Bouki” and get it to a wider audience. Few other major directors make classic cinema such an ongoing cornerstone of their work and then, as in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” question how it crafted their flawed understanding of America.