CINEMA MORRICONE IN CHICAGO

Updated: Monday, March 18, 2024 10:43 PM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | March 2024 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Here's more:

As a film, Scarface has largely one pounding note to play—one filled with extraordinary levels of violence and drug usage (including Pacino going facedown in a huge pile of coke, and taking more bullets to the chest and still standing than any human ever). And it plays that note relentlessly for the entirety of its extended running time. There is a boldness in the film’s extreme approach that can be both exhilarating (De Palma’s camera movement is exquisite) and exhausting. Scarface is all just so much much.And yet there is an undeniable propulsion in the film, a ferocity that exists throughout that cannot be easily dismissed. It really says something that Pacino, who played the legendary film gangster Michael Corleone in two of the greatest films ever made (Godfather I & II), might have eclipsed that seminal character with Tony Montana in the eyes of crime-film lovers. As his reluctant paramour and later recalcitrant wife, Pfeiffer gives one of the great ice-queen performances in the history of cinema (I swear, her bangs and bob were cut with steel). Written by Oliver Stone, the film is chock-full of quotable lines and in all technical aspects, Scarface looks and sounds remarkable.

The question I suppose is to what end? What are we to take away from all of the sturm und drang displayed in Scarface? There’s a great scene late in the film, when an over-coked and over served Montana humiliates Elvira, makes a spectacle of himself in front a full house of a Michelin-starred restaurant, and turns to the milky-white patrons, dresses them down for their own largesse, and says, “Say good night to the bad guy.” In that moment, De Palma’s film asks some interesting questions about capitalism and who benefits from it. I wish the film would have delved deeper into that theme as opposed to settling for being a “wonderful portrait of a real louse.”

That being said, I cannot disagree with Roger Ebert’s assessment, even though it seems that many who have seen (and will see) Scarface will find what I would consider a strange and abiding love for that louse. Regardless of whether one is repulsed or invigorated by the film (or, maybe like me, both), what Scarface eventually reveals to us is less about what happens to the people on screen, and more about how its massive cult following has responded to it. Depending on your perspective, I suppose the film can be seen as “just a movie,” or a reflection of our large-scale societal affection for those who are unapologetically bad. De Palma’s Scarface prefaced the era of the TV anti-hero (see The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Ozark, and so on) but followed on the heels of films like The Hustler and Bonnie and Clyde—movies about the disreputable and our attachment to them.

Scarface wasn’t so much new or groundbreaking, as much as it was the most pitched variation on that theme. It’s hard to imagine films like Natural Born Killers or Fight Club without De Palma’s still troubling “classic” gangster epic. A distinction that one may have trouble wrestling with depending on how they feel about those aforementioned films.

One thing is clear though: The audience for “the bad guy” is in no way ready to “say good night.” Not on film. Not in real life.

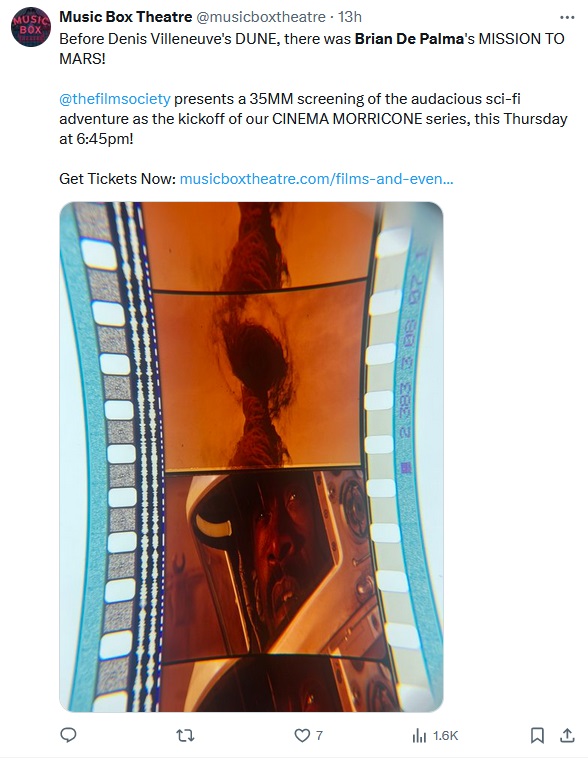

Somewhere between 400 and 500. That’s a lot of film scores for one composer in one lifetime to write, and orchestrate, and store in the memory banks of millions of listeners worldwide.The Italian maestro Ennio Morricone (1928-2020) hardly needed more than a handful of those scores for him to gain entrance to the realm of screen theme immortals. The howling-coyote signature melody for director Sergio Leone’s “The Good, the Bad and Ugly,” parodied to death for nearly 60 years now, would’ve been golden ticket enough.

But what if he had stopped there? Unthinkable! Decades and hundreds more movies, diminished. We wouldn’t have Morricone’s indelible evocations of nostalgia, and loss, and hope, in “Days of Heaven” or “Cinema Paradiso” or “The Mission.”

We wouldn’t have the rest of his collaborations with Leone, including “Once Upon a Time in the West.” Or – maybe my favorite, though I’ll change my mind by tomorrow – Morricone’s rousing sonic portrait of 1930 Chicago for Brian De Palma’s “The Untouchables.” The film itself may be factually ridiculous because it cares not about sticking to the historical record. Welcome to the movies! The score creates an aura of myth, from the first notes of the threatening marvel under the opening credits.

This Thursday the Music Box Theatre launches “Cinema Morricone,” sponsored by MUBI. It’s a weeklong, 17-film festival of movies, famous as well as obscure, celebrating the sheer scope and earworm mastery of this composer.

With one foot in the avant-garde and the other in mainstream classicism with a huge dash of pop, Morricone embraced the film medium’s innate capacity for violence (John Carpenter’s “The Thing,” screening March 22 and 27). Also its ability to break, heal and warm hearts on screen and in the audience (Giuseppe Tornatore’s achingly nostalgic “Cinema Paradiso,” March 24 and 25).

The Leone/Clint Eastwood/Morricone “ Man With No Name” trilogy takes its rightful place in the festival, along with “The Untouchables,” and some less venerated titles from the windmills of your mind. “Red Sonja,” for example (March 26-27), the Sandahl Bergman/Arnold Schwarzenegger ode to sword, sorcery and cheese. These are just a few of the titles, and “Cinema Morricone” concludes March 28 with the documentary portrait “Ennio,” directed by his friend, collaborator and “Cinema Paradiso” director Giuseppe Tornatore.

How did one man write so much so memorably, showcasing a pan flute here, an ocarina there, operatic sopranos and harmonicas and whistling (so much whistling!) everywhere? To further my musical smarts a little beyond the level of “it’s cool, therefore I like it,” I talked to Columbia College Chicago’s Kubilay Uner. He directs CCC’s Music Composition for the Screen Master of Fine Arts program. Uner also has composed for movies (“Force of Nature”), theme park rides (Corkscrew Hill at Busch Gardens) and video art installations (he’s in the permanent collection at Los Angeles County Museum of Art).

Q: Here’s a quote from “Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words,” conversations with Alessandro De Rosa, where he’s talking about music’s main function in relation to what’s on the screen. He quotes his friend Gillo Pontecorvo: “My friend used to say that behind every story cinema tells, there is a real story, one that really counts … music must find a way to bring out the value of that hidden story and highlight it.” That’s a really intriguing description of a film composer’s role, don’t you think?

A: I think all film composers can relate to that. There’s something fundamentally useless, most of the time, if you’re just duplicating with music what the film is already doing. Now, there are exceptions. Sometimes you want everybody (executing) the same moves for maximum impact, so the visuals, the storyline, the acting, the editing and the music all push one thing. That’s great for a high-intensity fight scene. But a lot of the time, and what Morricone’s so smart about, is what he’s describing in that quote, which is more prosaically called the subtext. There, the question for the composer becomes: What’s actually happening in the scene? It’s an essential description of what film music is supposed to do. Q: Morricone started as an arranger, and got his first on-screen composing credit for “The Fascist” in 1961. His output is staggering, across six different decades. Do you think he ever felt burned out, or that he’d sold out? A: I don’t think so. I don’t think you can write close to 500 scores with themes of his quality without believing in them. Even in his most accessible film scores, he’s pushing boundaries somewhere, with interesting chord progressions you just don’t hear in other movies.

Q: Until a decade or two ago I didn’t realize Morricone, and other film composers, often composed and sometimes recorded music before a film was actually shot. De Palma, in one interview, talks about “The Untouchables” (March 22 and 26), which is a score I love. Morricone read the script and met up with De Palma in New York for a few days and talked, and Morricone wrote several versions of four main themes for the picture on that trip. That kind of impressionistic film scoring versus scoring specifically to the director’s images —

A: — It does lead to a different result, obviously. I’m extrapolating, but I wonder if it aids in creating a kind of parallel story, the story underneath the story, that Morricone mentioned in that quote from the book. It’s not a super rare approach; some of the music by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (Oscar winners for “The Social Network” and Pixar’s “Soul”) I think was written that way. There was some criticism leveled at them from those who believe that isn’t really scoring in the purest sense. But think about the very beginning of music and movies: It was some dude sitting at a piano with a book of classical themes in the public domain, themes sorted by emotion or whatever. Love scene? Boom! Something by Brahms! Chase scene? Boom! Wagner! That’s how it all started, in a way.

This is a slideshow worth viewing, as Chachowski's writing about the films throughout is much better than the average click-bait slideshow, and he does seem to be familiar with De Palma's work. Check it out.

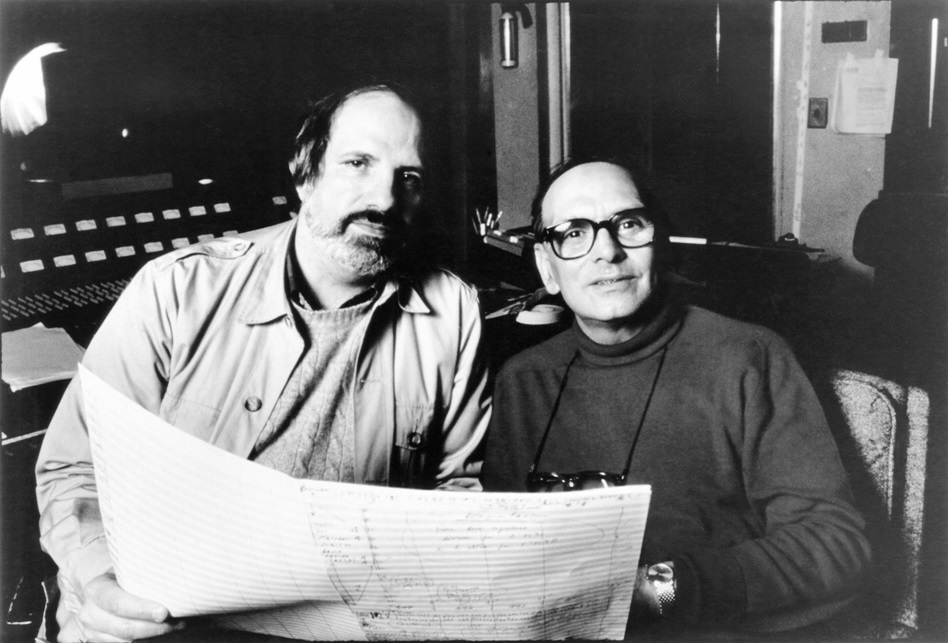

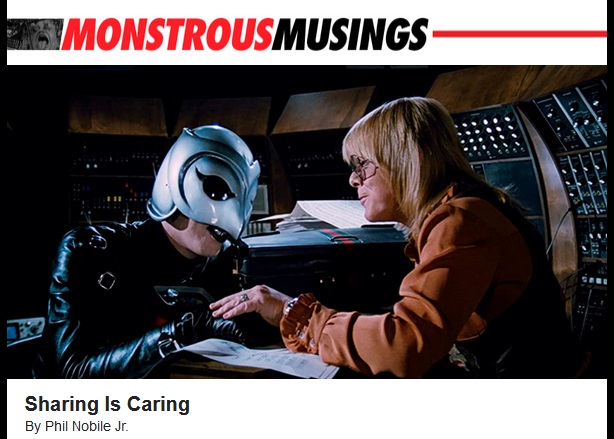

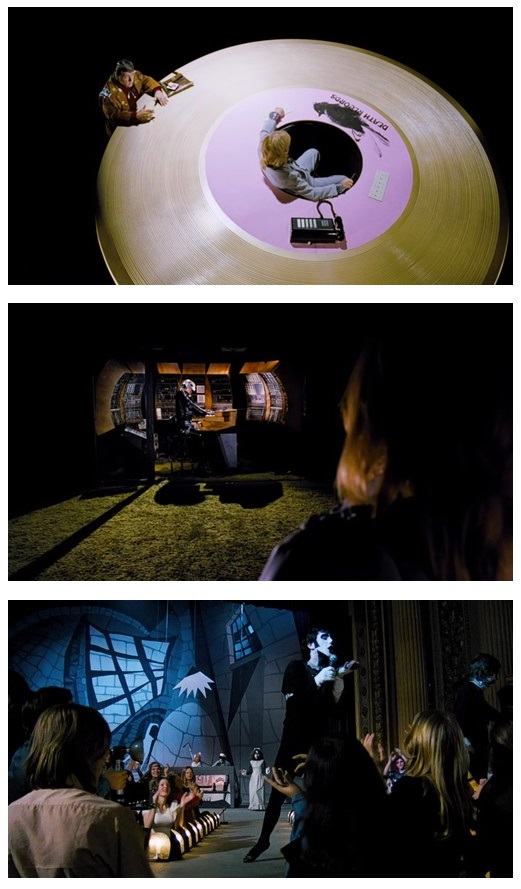

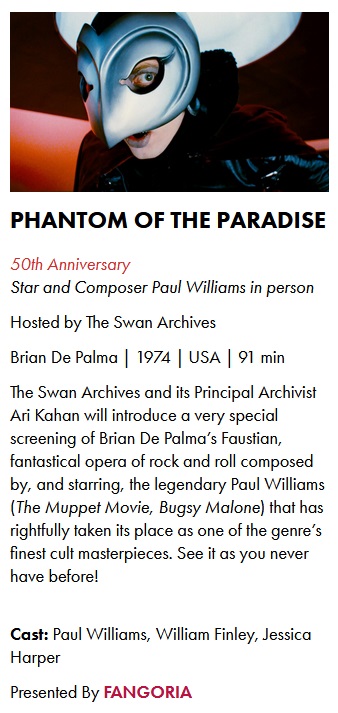

Anyway, it’s incredibly fun to come up with an evening’s entertainment for my comrades in kino, and those fleeting moments have fueled a low-key jealousy of the friends and acquaintances I have who get to do it full time (-ish). So you can imagine my elation when a phone call I made to Landon Zackheim, co-founder of the Overlook Film Festival in New Orleans, during which I pitched him a special screening for the 50th anniversary of The Phantom of the Paradise, was received so well.I’m a pragmatic sort, so I pitched a scalable event, with removable parts and contingency plans, in the hopes that if we got a “no” on one front, we’d get a “yes” elsewhere, and end up with SOME version of this event for the fest. But yesterday The Overlook announced their lineup to the world, and I’m excited to say the Phantom event is the ultimate version Landon and I dreamed of.

First off, there’ll be an entertaining, informative and often hilarious presentation on the history, trials, tribulations, and persistence of Brian De Palma’s 1974 glam rock horror musical, given by Ari Kahan of The Swan Archives; next, a screening of the classic film itself, giving some Overlook audience members their first-ever chance to see the movie on the big screen (at the beautiful, historic Prytania Theatre, no less); and finally, an in-person conversation with the great Paul Williams, Phantom’s villainous star and composer. I kind of can’t believe it’s actually happening.

And to be clear: I did NONE of the work. I had an idea of how *I* would love to see the film presented, pitched it, connected a person or two to the fest, and Landon and his team made it happen. (Then, no less crucially, Fango agreed to sponsor it.) And my understanding is that Phantom is a film that the Overlook’s late artistic director Doug Jones had been hoping to screen at the fest for some time, so I humbly recognize that I’m just a small part of the universe’s larger plan here. But the excitement in Landon’s voice upon hearing my pitch, and the incrementally growing excitement in his voice with each new update — man, that’s a buzz I could get used to. And it’s a buzz I’ll be riding right up to the moment this screening ends… and let’s be honest, probably for a couple weeks afterward.

This screening will likely be the culmination of my 40-plus-year relationship with this movie, sure, NBD, but at its core it’s just a bigger version of showing people you like a movie you love, which is an attainable and relatable buzz for all of us. I think that tradition has been diminished in recent years as we text and DM each other links all day, and maybe fewer folks are sitting down to actually watch the thing you’re recommending (I know firsthand that folks will do anything to NOT leave the platform on which you’re sharing an external link with them). But it does still happen; Shudder and Screambox are basically platform-sized versions of this, with passionate movie lovers finding and sharing with us films they absolutely love. Certainly Joe Bob Briggs is the role model for this activity, championing lost classics on his show and converting his congregation to one new-to-them title or another every episode.

I bet the film fest programmers, the streaming programmers and Mr. Briggs alike would agree that curating films for our tribe is, on any level, a buzz worth chasing on both sides of the transaction. It’s probably tied to our innate desire to share and tell stories; maybe that’s what that dopamine hit I’m feeling right now is about. But, and not to put too much pressure on the next Blu-ray you loan out, it’s also ultimately how the movies we love gain immortality. It’s important and it’s needed. So fire up those recs, those links, those discs, get out there and spread the good word.

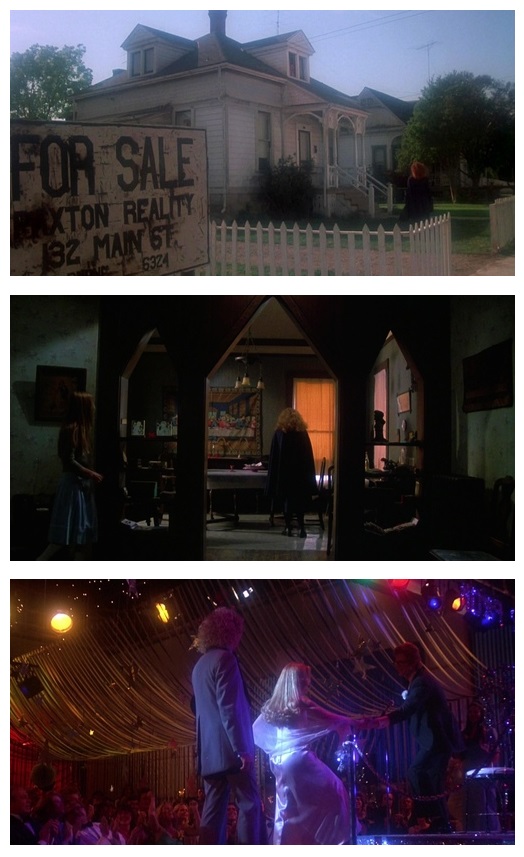

Born in Canton and raised in Ipava, Illinois, Jack Fisk didn't study cinema or any performing arts, for that matter. His background was in painting, having gone to the Cooper Union and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. There, he started to explore the medium of sculpture, free to experiment with large-scale work that, in his own words, looked better when you were walking around them. In other words, he was building environments rather than a piece to be observed from a static distance. He attended college with childhood friend David Lynch, whose acceptance to the AFI prompted the pair to go West, to California. There, Fisk found work on movie sets, like a non-union gig managing traffic for a shoot.Inevitably, he found his place in the art departments of small productions, such as the Jonathan Demme and Roger Corman-produced Angel Warriors. In that project, he worked alone and learned the necessities of set dressing, which, until then, hadn't crossed his mind. Still, cinema was a job to Frisk until one production opened his eyes to its possibility as an art form. It was Badlands, and Fisk got his job after knowing of Terrence Malick through Lynch – their time at AFI overlapped – and feeling curious about the film's premise. Mostly, the art director wanted to try his hand at a period piece, even if it was set in the not-so-distant past of 1958. Learning to work with this new director was a wild experience, a repudiation of mechanical filmmaking practices and a love for artistic freedom.

Take the treehouse inhabited by the runaway lovers. There was no such thing in the script, but Fisk suggested it to Malick, took a day to build it, and they were shooting there by the next sunrise. With no storyboards and such fluidity, he became more aware of the world-creating magic of production design, intuitively relating spaces to each other to generate ideas, blending actual location with scenography to invoke a seamless feeling of immersion. Moreover, the director's methodology often involved creating something even more expansive than what ended up on the screen, being ready for any eventuality, the camera's will.

Fisk has described Malick as a brother, but it was also on the set of Badlands that he met his wife, Sissy Spacek. Less than a year after the film saw the light of day, they were married, and she soon started working as a set dresser between acting jobs. Spacek's first art department credit came in 1974 when Fisk got a job designing the theatrical lunacy of Phantom of Paradise. It was the first of the couple's two collaborations with Brian De Palma since the thespian managed to win the role of Carrie White, and Fisk also designed the 1976 Stephen King adaptation. Far from the only genre pictures he made during this time, such projects proved that this artist could thrive beyond realism.

But between horror and blaxploitation, indie nightmares and musical fantasy, Fisk's "brothers" pulled him into their own worlds at the height of New Hollywood. For Lynch, he was Eraserhead's The Man in the Planet, and for Malick, he was the man in charge of bringing to life Days of Heaven's farmland poem. Inspired by historical photographs and the director's idea of a three-story Victorian house lost in the middle of a wheat field. In his most lavish production up to that point, Fisk found himself working the land like the characters, seeing that engaging with the picture's reality helped him as a designer. His achievement is also a treatise on the power of emptiness in the cinematic frame and the lyricism of light.

The Overlook Film Festival is one of the country's best genre fests, an annual party that combines some of the most exciting new horror films, rep titles and special guests with wholly unique immersive experiences that you simply won't get anywhere else. Today, the fest has announced this year's full lineup, and ... phew, they've really outdone themselves this time! The 2024 Overlook Film Festival lineup is possibly the best it's ever been.A special point of pride for us this year: FANGORIA is presenting a 50th-anniversary screening of Brian De Palma's Phantom of the Paradise, with none other than Paul Williams in attendance, as well as a special lecture about the film's history by Swan Archives' Ari Kahan. We couldn't be more excited to be bringing this special event to the Overlook.

"Then awards season came along and, as usual, crushed all my hopes and dreams.

"Barbie lost out on nominations for Best Director and Best Actress, for Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie respectively. A backlash strong enough to rope in Hillary Clinton followed. Much of the backlash included accusations of sexism on the Academy’s part, which, given their historical and ongoing aversion to female directors, cinematographers and visual effects artists, makes sense. But the backlash framed Barbie as female in some deeper, more intrinsic sense than, say, Anatomy of a Fall, directed by Justine Triet and with a cast led by Sandra Hüller, both of whom were nominated. Barbie was not just by women, but for women.

"'Did too many people (particularly women) enjoy Barbie for it to be considered ‘important’ enough for academy voters?' Mary McNamara questioned in the LA Times, '… Was it just too pink?'"

From this set-up, Moloney dives into what, on the immediate surface, seems like a completely absurd notion: that Brian De Palma's Scarface is "the girliest, pinkest movie in the world." The tone of the piece is playful, and yet... one can't help but sense there might be at least a tiny bit of truth in what she is saying:

I tried to think of other girlish, pink movies that didn’t get their due accolades on release. Dirty Dancing doesn’t count, obviously, since that’s a class conflict sports movie in the vein of Rocky. Every man I’ve ever met loves When Harry Met Sally. But of course, the girliest, pinkest movie in the world was robbed of even an Oscar nomination: Brian De Palma’s Scarface.Since its release in 1983, consistent efforts from film critics, rappers, and dorm poster salesmen to assert the macho masculinity of Scarface have failed to erase this simple truth: Scarface is a fairy princess story wrapped in pink, purple, and cyan. Both its score and soundtrack are exuberantly feminine dance-pop from euro disco pioneer Giorgio Moroder. Can you imagine any of the many, many hip hop songs inspired by Scarface rubbing shoulders with Debbie Harry, Amy Holland or Elizabeth Daily on the film’s actual soundtrack? I cannot, and that includes the ones that literally sample music from Scarface.

The film’s girliness is exemplified in the “Push It To The Limit” montage, which pulses to a beat much closer to a makeover montage than a rising-to-power one. It’s set to a relentlessly upbeat bit of synth that would make any Death to Disco advocate throw up. And it’s not creating an ironic contrast between that music and the images: it doesn’t just sound like a makeover montage, it looks and feels like one, too – with images of Tony’s sister Gina (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) trying on outfits at the store, not to mention the opening of her beauty salon (in a perfectly pink palette, of course) and Tony’s wedding to Elvira (Michelle Pfeiffer), featuring his new pet tiger.

Tony’s banker calls his wife Elvia “the princess,” but he’s got it backwards. Elvira is a Prince Charming: an American-born WASP, gorgeous in her slinky backless dresses, she is a conduit to and symbol of power and privilege, a cipher onto which men can project the American Dream. Tony Montana is the princess – not the kind that exists in reality, born with a silver spoon in his mouth, but that kind that exists in fairy tales. Pauline Kael complained that Tony seemed “to get to the top by one quick coup,” with no sense of his rise there. But it’s not that it’s a typical gangster story with parts missing. Tony is Cinderella. He’s Evita. He’s Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. He’s plucked from the gutter to the palace in one fell swoop.

And with that one fell swoop, he puts together his own Barbie Dreamhouse of material consumption, complete with a ginormous bubble bath and a pink neon sign in the foyer: “The World Is Yours.” He changes outfits with the regularity of Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra, an assortment of suits in endless colours. And when he has it all, he stares into the middle distance, alone, in a pink-lit nightclub, like a sad rich girl in a Sofia Coppola movie.

Scarface is feminine deep in its bones, even more so than Barbie – De Palma would never have allowed a Matchbox Twenty song to intrude. (Maybe “Smooth” by Santana feat. Rob Thomas.) If we insist on gendering movies, and doing so on the basis of aesthetics, we must face up to this simple fact: Scarface is for girls.

- I got the cooperation of Brian De Palma, which was very important

- I got Oliver Stone on board

- I got a lot of people on board

- And we kind of did the same drill as the Goodfellas book: we have a making of, we have a scene-by-scene breakdown

- Scarface has an even bigger cultural footprint than Goodfellas (which itself is pretty well-known and widely-quoted)

- And I hope to get De Palma involved in some promotional projects. We’re doing a launch on May 14th at The Mysterious Bookshop, in downtown Manhattan, my favorite book store. We’re doing other events, as well. And I hope Brian will come along for some. I think Steven Bauer will certainly be involved. I had the best time with Steven Bauer, the guy who plays Manny. He gave me the most stuff.

- I got Michelle Pfeiffer, which is not an easy get. But I did get her. And she was great. She was lovely. She’s so interesting, because, you know, she’s very frank about her experience. She’s proud of the work that she did on the film, but she said every minute on the set was torture. And it wasn’t because she was being mistreated or disrespected by anybody, it’s just her level of confidence was so low, she was always afraid that she was screwing up. She had no kind of feeling for the value of what she was doing, and she was miserable.

- [William McCuddy cuts in: “But that works for the film – she looks frightened all the time.”

- Yeah. Well, the one thing, the one direction that Brian always gave her – and she talks about Brian being very good and very sympathetic – she says, but Brian, after every take, the one thing he would ask her was, “Did you smile?” Because she wasn’t supposed to smile. You know, there was a notion that she would try to warm the character up just a little bit, and Brian said, “I appreciate you want to do this, I know you have the ability to do it, but for the purpose of the role, you can’t do it.” Although there is one scene where she does it, and I won’t say what it is. But when you read the book, we go into it, and it’s an improvised scene. It’s a scene between her and Pacino where she does laugh.

- Bauer’s origins

- Pacino’s accent and how Bauer influenced it

- Charles Durning and Dennis Franz dubbed lines in opening interrogation

- De-myth of Spielberg directing a shot

- Pacino decided to write his own book, and so did not participate in Kenny's book

- Bregman/Pacino fallout over Born On The Fourth of July

- Jeff Wells sneaking onto Scarface set at mansion

- McCuddy fascinated by New York portion of film within this Miami story

- Entertaining chapter about R-rating due to testimony of a film critic

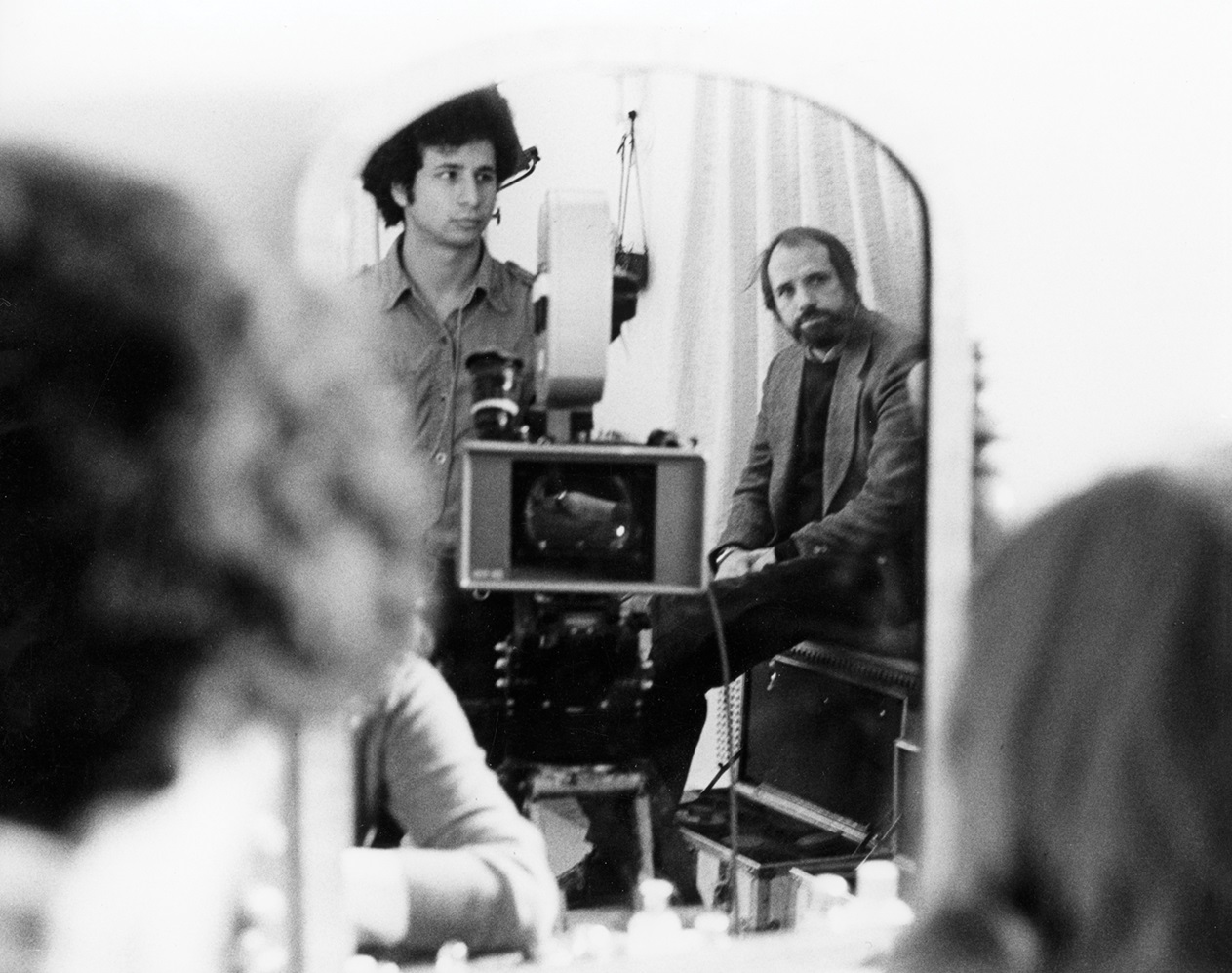

The article includes the photo above, showing Fierberg and De Palma on the set of Home Movies in 1979. Fierberg went on to be director of photography on Charlie Loventhal's The First Time, a feature that Loventhal co-wrote with Susan and William Finley. Fierberg was also the cinematographer on Sam Irvin's directorial debut, a short titled Double Negative, which William Finley appears in.

Here's the first part of McCarthy's profile article:

Steven Fierberg, ASC, points excitedly at a canvas by Jean-Michel Basquiat during a recent tour of L.A.’s The Broad museum. Titled Melting Point of Ice, it has an angry face, a spread-eagled elephant, an eye with teardrops of blood. He notes wryly, “Now that is my world — reds and blacks, anger, the world isn’t working, poverty, people suffering…”As Fierberg tells it, his vision germinated in dark spaces, including the depressed neighborhoods of Detroit, where he was born, and the punk underworld of New York City, where he started his film career. But as people who have worked with him will quickly point out, the cinematographer’s instinct is to shine light into that darkness and make space there for the human heart. “Steve is built on love,” says director Julian Farino, who worked with him on HBO’s Entourage. “He has the biggest heart, and endless love for humanity.”