Late in Don DeLillo’s classic novel “White Noise,” a scholarly friend discussing cinematic car crashes tells the story’s protagonist, “Look past the violence, Jack. There is a wonderful brimming spirit of innocence and fun.” In the book, it’s one of many absurd platitudes the characters use to make sense of a nonsensical world. In Noah Baumbach’s adaptation, it’s part of the opening scene: The scholar (Murray Siskind, played by Don Cheadle) screens a reel of stunt crashes for his students, and his comments set the tone for the film. The violence of the novel is there — man-made disaster, attempted murder, Nazism — but for perhaps the first time in a Baumbach film, so is a pervasive spirit of innocence and fun, along with an eye-popping visual flair he’s kept concealed for far too long. Whereas the book built up a kind of fatalistic resignation, Baumbach’s version of “White Noise” is genuinely exuberant. Case in point: In a closing supermarket scene, DeLillo described shoppers as “aimless and haunted.” In the film, the same moment ends in an eight-minute dance number incorporating the expansive cast.

Yet framing this as a dichotomy glosses over the complexity of the source material. At the heart of the novel was always a bubbling domestic comedy, and not of the bitter, dysfunctional kind we’ve seen in previous Baumbach films. Jack Gladney (Adam Driver) and his wife, Babette (Greta Gerwig), truly care for each other; the marriage glows with tenderness. Baumbach runs with their children’s antic energy and lets it suffuse other parts of his film, animating even the story’s more difficult third part with humor and affection that reflect the book’s tone. Rather than betraying the novel’s savage critique of modern life, Baumbach’s approach illuminates DeLillo’s humanism in the director’s least cynical film since “Kicking and Screaming” — and easily the most daring he’s made.

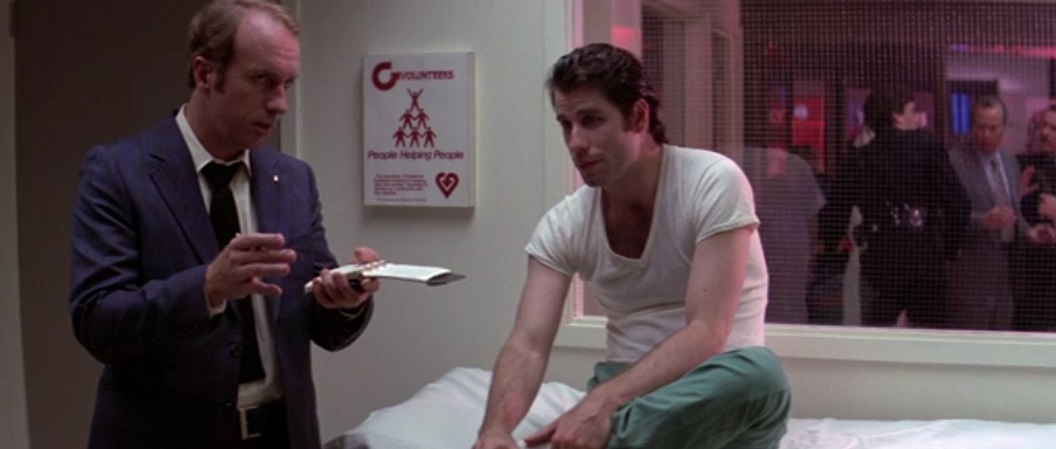

Like the novel, “White Noise” the film contains three distinct parts. “Waves and Radiation” introduces us to the Gladney family and Jack’s academic work in his first-of-its-kind Hitler studies department. “The Airborne Toxic Event” tracks an industrial chemical leakage that throws the family’s life into crisis. “Dylarama,” taking up the second half of both book and film, documents Babette’s clandestine participation in an unsanctioned medical trial.

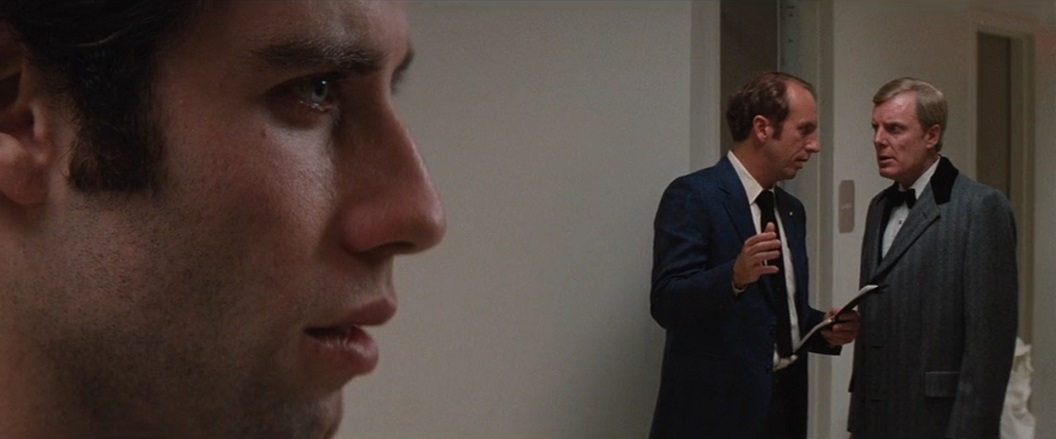

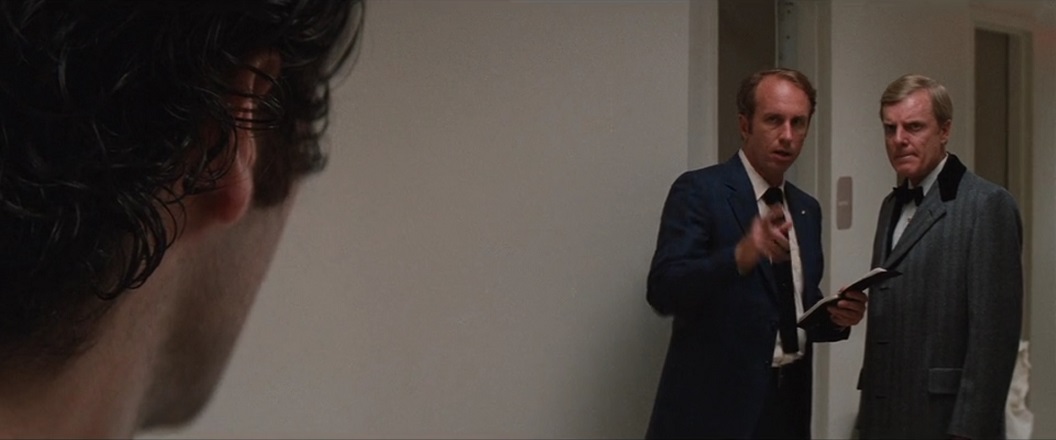

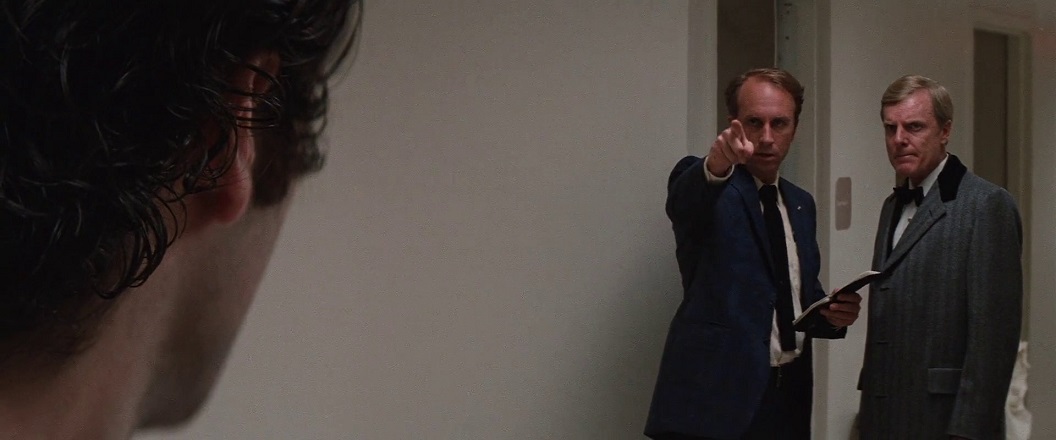

Remarkably, the intellectual satire, environmental disaster tale and noir coalesce more smoothly in Baumbach’s movie than they did in the novel. A shadowy rogue pharmaceutical figure who dominates the story’s third part now drifts like an apparition through its first and second, rather than disorienting with a late entrance. More significantly, Baumbach makes a bold and divergent choice to bring Babette into the climactic confrontation and its fallout. Her presence adds a valuable grace note, contributing to the film’s surprising optimism.

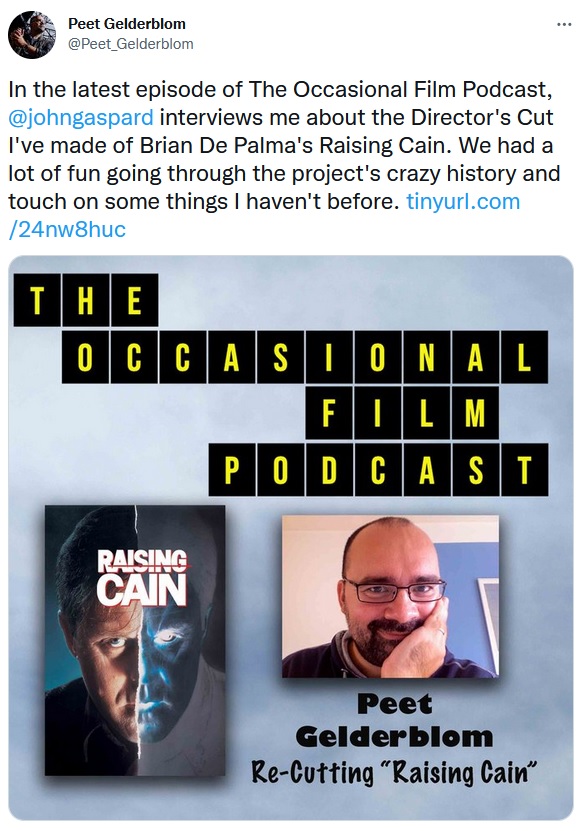

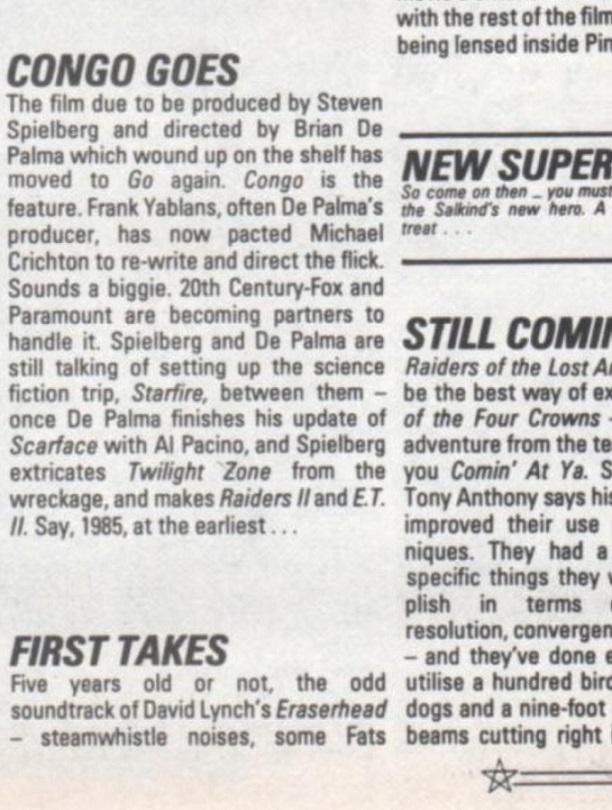

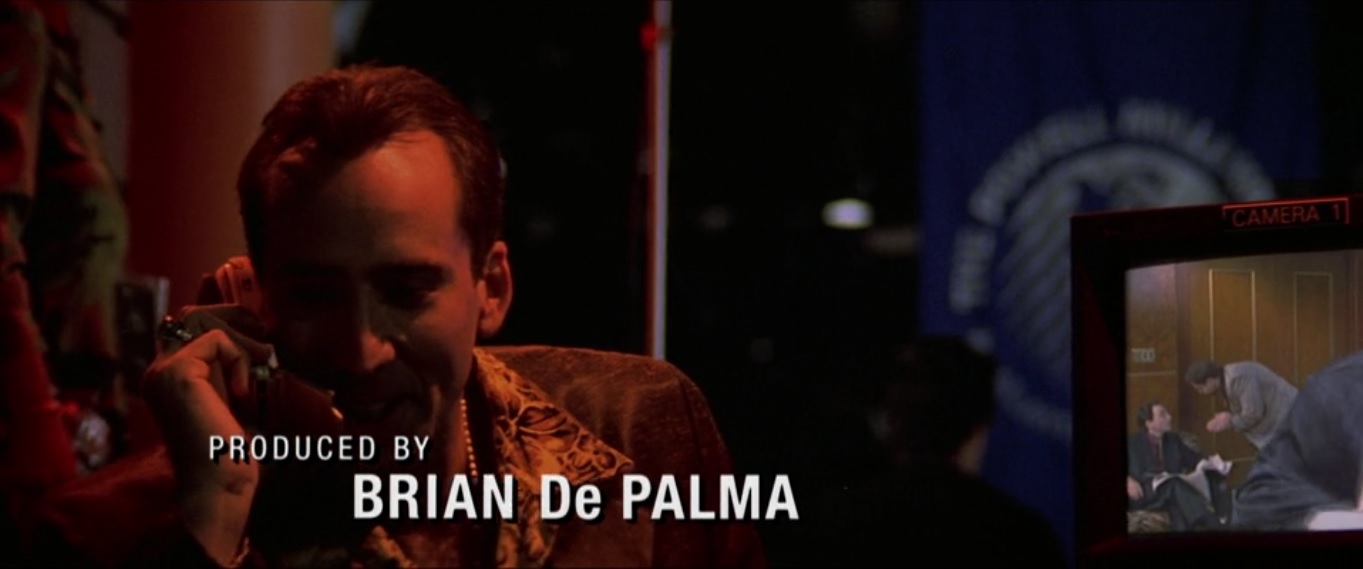

It was Brian De Palma, not a purveyor of innocent fun, who suggested Baumbach consider an adaptation to try things Baumbach’s own scripts wouldn’t allow. The latter filmmaker co-directed a documentary about De Palma in 2016, and at the time, they seemed an unlikely duo: the elder an auteur of the lurid and gruesome (originals such as “Blow Out,” adaptations including “Carrie”), the younger firmly planted in the confines of grown-up mumblecore (“Greenberg,” “Frances Ha”).

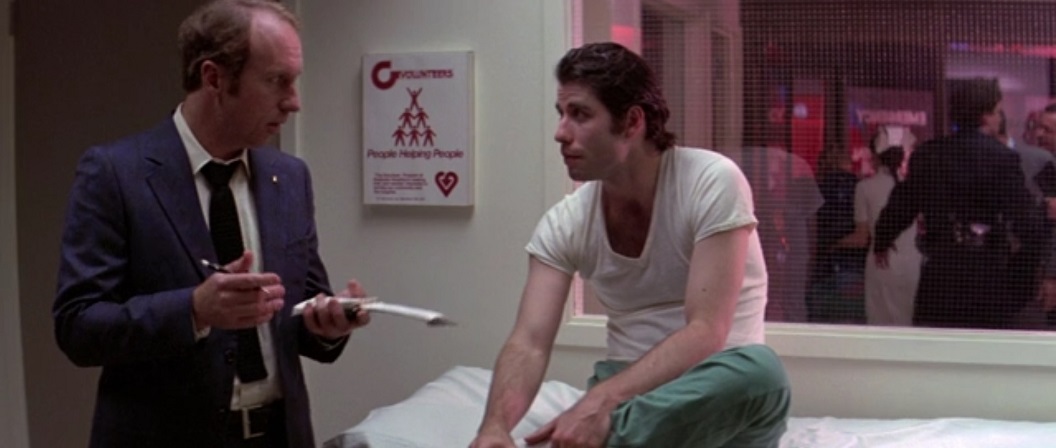

Watching “White Noise,” though, the pairing begins to make sense. Who knew Baumbach had it in him to choreograph intricate crowd scenes, crane-shoot crashing and combusting trains or stage a payback shooting at a sleazy motel bathed in neon-lit De Palma shades? Certainly no one familiar with Baumbach’s filmography, in which the most striking image to date was of two silent people in an empty subway car.

Despite its long-assumed unadaptability, DeLillo’s story contains a number of memorable visual moments, and Baumbach takes advantage. A first-act set piece takes place in a classroom so impossibly twee it seems like a tribute to past collaborator Wes Anderson. But what starts off as a composition of colorblock and Fair Isle takes on sudden urgency in Baumbach’s hands. He splices in not only relevant found footage but also the toxic event’s precipitating accident, about which the book barely speculates. In the process he draws a line from mass hysteria to human carelessness, the results of which can be similarly catastrophic. And isn’t that the theme of these last few years?

The emergency response to the Airborne Toxic Event is the centerpiece of both book and film, and Baumbach brings it to life with flourishes of his own: Seussian air-purifier trucks; hazmat suits a little more fabulous than they need to be (credit to Ann Roth, who costumed De Palma’s “Dressed to Kill”). DeLillo wrote that “The toxic event had released a spirit of imagination,” and we tour the evacuee camp to behold mythmaking and conspiracy-theorizing in progress. Rather than despair over obvious present-day parallels, however, Baumbach limits fake news to folk songs and puppet shows. During the madcap flight from the camp, he sends Jack on an off-tackle run for a lost toy.

While the third act still plunges us into more chilling waters, Baumbach guides us with familiar signifiers. A chemistry lab looks like it belongs to Bunsen and Beaker. A visit to the A&P packs in maximal advertising language. And in an impressive coup, German legend Barbara Sukowa presides at the German hospital where Jack lands near the story’s end (now with Babette in tow). As Sister Hermann Marie, Sukowa brings to bear the weight of past roles when lecturing on grief and magical thinking: philosopher Hannah Arendt, mystic Hildegard von Bingen, prostitutes and militants. Attending nuns push not gurneys but shopping carts, leavening the tragic with the mundane. By the closing dance sequence, Jack and Babette have faced their worst fears and emerged unified. For its trouble, the town earns its evident joy.