'WHITE NOISE' OPENED NYFF LAST NIGHT, AFTER PREMIERING IN VENICE IN AUGUST

Noah Baumbach's adaptation of Don DeLillo's White Noise won't be released until the end of December, but reviews have been coming out of film festivals in Venice and New York:

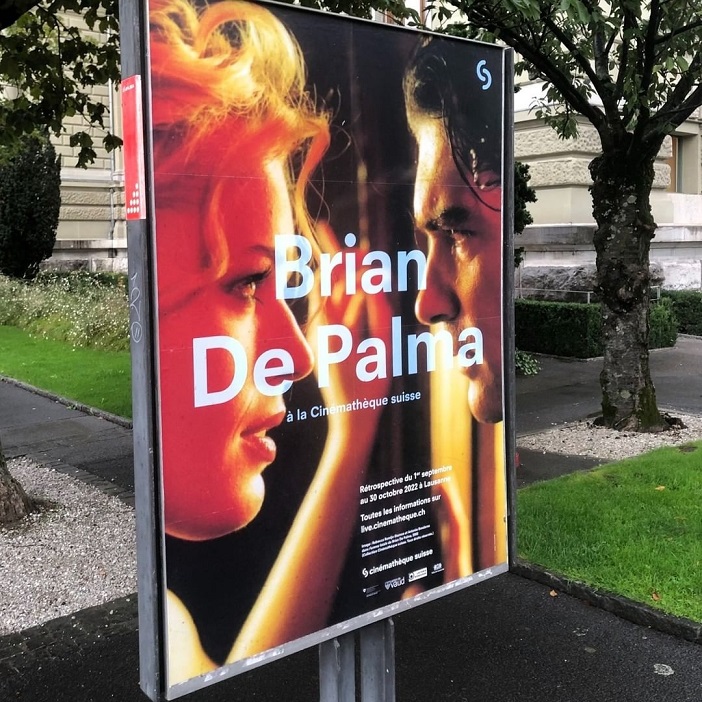

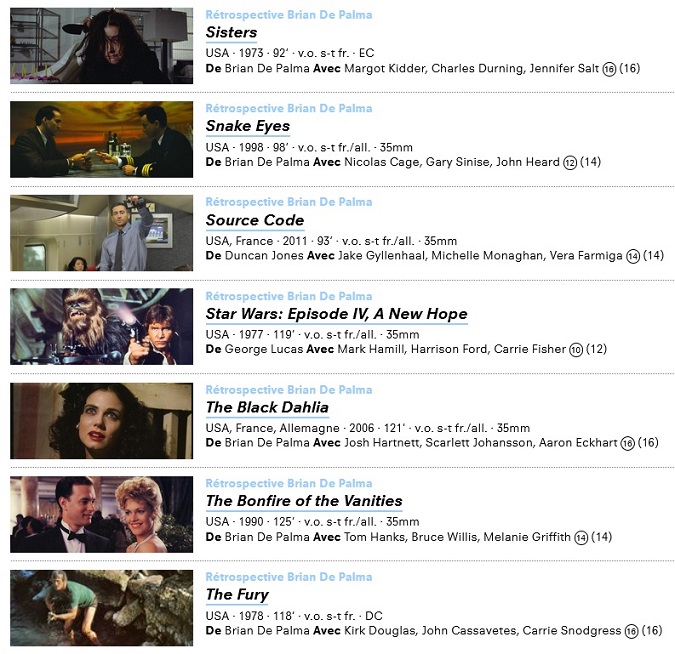

Based on the 1985 novel by Don Delillo, White Noise is a far more ambitious film than director Noah Baumbach’s last effort, the popular 2019 drama Marriage Story. His influences, such as the American disaster movies of the 70s and 80s, the rom-com of that era, the family on vacation movies, as well as the high-octane thrillers of directors such as Brian De Palma, are all evident here in the tonal shifts, the technically assured and stylish look of the film, the flashy action scenes, the looming disaster of a toxic, chemical cloud, the large family bundled into a car and the verbal back and forth of the central married couple.

David Ehrlich, IndieWire

If the first act of “White Noise” feels like a work of expert-level pantomime, the similarly faithful second act somehow creates an energy all its own. Baumbach knows that DeLillo anticipated the likes of “The Matrix,” “The Truman Show,” and scads of other stories in which reality becomes a simulation of itself, but those aren’t the movies he wants to remind you of here. A crucial difference between the “White Noise” of 2022 and the “White Noise” of 1985 is that Baumbach has already seen the movies that DeLillo’s book helped to inspire, and that frees him to have some fun with this one.As Jack, Babette, and the four younger members of their blended brood (a terrific group that also includes Raffey Cassidy and May Nivola) attempt to flee the airborne toxic effect, trying to suss out how safe they should feel amid the traffic jam of other families trying to do the same thing, Baumbach switches to a register that we’ve never seen from him before. Suddenly we’re in “War of the Worlds” territory, complete with oodles of Spielberg Face and a menacing awe so artful and evocative that it feels more like the real thing than a commentary on it. Something I never thought I’d write about a Baumbach film: The CGI is fantastic.

The evacuation sequences viscerally convey the appeal of disaster movies by clinging to a character who refuses to accept that he’s in one (at least at first), or to acknowledge that death can still find him in a large crowd. Baumbach’s visual language ensures that we have no such trouble. We’ve seen “Independence Day,” “Deep Impact,” and enough films of its ilk to recognize what a massive disaster supposedly looks like, but Jack — living in 1985 — doesn’t have the same frame of reference. To him, his situation doesn’t feel like a movie, and so he’s slow to recognize it as a disaster (a phenomenon illustrated in the brilliant shot of a black cloud swallowing the glow of a Shell logo just above Jack’s shoulder). We have the opposite problem, and it epitomizes why “White Noise” may be even more relevant today than it was 37 years ago: When we reckon with a disaster that seems too much like a movie, we struggle to accept that it’s real. As a character puts it in the book, and possibly also in this film: “For most people there are only two places in the world: Where they live and their TV set.”

Baumbach has an absolute field day with this dissonance; the closer his characters veer towards danger, the more that Baumbach exaggerates the movie-ness of their existence. A dramatic car chase is shot like a scene from an ’80s road trip comedy like “National Lampoon’s Vacation,” complete with a slow-motion shot of the family station flying through the air. A climactic showdown in a seedy motel — the end of the Dylar affair — drips with De Palma, all the way down to an unmissable split-diopter shot.

It’s a good thing the movie’s semiotic pleasures are so pronounced, because the book’s more basic charms don’t quite survive the trip to the big screen (let alone the ride home to Netflix). That third act gunplay is typical of an adaptation that’s always smart and on edge, but seldom involving enough beyond that. DeLillo’s writing gives readers the space to see their own existential terror reflected back at them in the funhouse mirror of Jack’s absurd circumstances, but Baumbach’s “White Noise” — more externalized by default — proves too arch for our emotions to penetrate.

Baumbach’s film is so determined to feel like “White Noise” that it ends up wearing the novel like a costume, a sensation epitomized by its lead performance. Driver is far too young to play the 51-year-old Jack (even if 38 was the 51 of 1985), though his middle-aged cosplay contributes to the general air of simulacra. More difficult to excuse is the actor’s struggle to sell the journey of Jack’s epiphanies. Driver is so naturally wild with life that he never quite musters the latent fear needed to fuel his character through the first act; it’s the same reason why the self-possession Jack finds in the third act feels less earned than it does inevitable. It’s a fitting anchor for an adaptation that gets everything so right that you might yearn for the friction that comes with getting it wrong, or at least the tension that comes from pulling away.

It’s no coincidence that the film’s most ecstatic moments — the first scene, the last scene, and the Spielbergian chaos that runs down the middle — are also the ones that most deviate from the book. Baumbach is ultimately too in sync with DeLillo for “White Noise” to escape from the shadow of its monolithic source material, as movie struggles to escape the hat on a hat sensation of that match between filmmaker and novelist, and often feels like the work of a third party who’s trying to imitate them both at once. All the same, you can still hear something almost subliminally divine under that uncanniness whenever Baumbach cranks up the volume. The sound of a beeping smoke alarm, perhaps.