AT VANITY FAIR - MODERNIST DESIGN & MURDEROUS VILLAINS

"HOW ONE MODERNIST BUILDING IN HITCHCOCK'S 'NORTH BY NORTHWEST' CHANGED CINEMA FOREVER"

At

Vanity Fair,

Christine Madrid French adapts her book,

THE ARCHITECTURE OF SUSPENSE: The Built World in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock, into an article that keys in on the Vandamm House in

Alfred Hitchcock's

North By Northwest:

After its momentous debut in The Black Cat, modernism did not appear as a villain’s lair again until Hitchcock brought it back in the mid–20th century with North by Northwest. The return of high-end modern designs on film corresponded with a critical shift in the portrayal of evil characters, morphing from a frazzled Dr. Frankenstein into a handsome Captain Nemo. Using cultivated gentility to cover malign intentions required an equally sophisticated architectural expression. One of Hitchcock’s first experiments with this portrayal is seen in The Secret Agent, in which he unveiled a villain who was “attractive, distinguished,” and “very appealing” to audiences, according to his biographer François Truffaut. Hitchcock moved forward from there with the belief that “the best way” to make a thriller work was to “keep your villains suave and clever—the kind that wouldn’t dirty their hands with ordinary gun play.” The building that changed movies forever makes its first appearance almost two hours into North by Northwest and is onscreen a mere 14 minutes. Filmic structures are “evanescent as a flicker of light,” as noted by historian Alan Hess. Nonetheless, this design had a penetrating and lasting effect in the public consciousness. The Vandamm House itself is now a movie star with its own dedicated legion of fans. The high-quality production design of the film, and the hybrid mixing of recognizable locations with studio sets, led to many inquiries as to the “real” location of the home. Explorations in the area behind Mount Rushmore would prove futile, however, as the building is entirely conjectural, a set created by production designer Robert F. Boyle at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios in Los Angeles.

Toward the end of the article, French moves forward to take a brief look at the work of architect

John Lautner and its appearances on film:

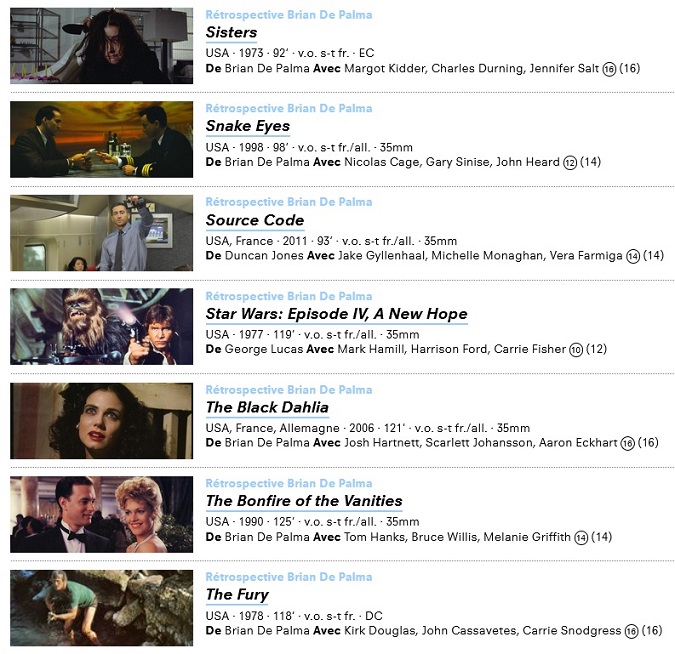

In the decades following the release of North by Northwest, filmmakers enthusiastically adopted Hitchcock’s architectural precedent, crafting fictional modernist structures and rediscovering designs in Southern California that could host a score of film villains introduced in the 1960s and ’70s. Architect John Lautner designed many houses during this period that later found fame as villain’s lairs. His tactile, sensuously curved, concrete spaces exude power in their boldness and unorthodox approach. Filmic creators also appreciated the cinematic scale and the ambitiousness and improbability of the designs. Ken Adam, production designer for the James Bond series of films including Dr. No, Goldfinger, Thunderball, The Spy Who Loved Me, and Moonraker, featured the Lautner-designed Arthur Elrod House in Palm Springs in Diamonds Are Forever. Bond (played with finesse by Sean Connery) tracked billionaire Willard Whyte to his lair in the hills, protected by the acrobatic Bambi and Thumper. The women swing from the modern lighting, leap from the living room boulders, and attempt to drown Bond in the sky-high swimming pool. The perfect hideaway for a villain. Director Brian De Palma selected the Chemosphere, another cliff-hanging Lautner design, for Body Double, a murderous homage to both Vertigo and Rear Window. The film, and the building, draw upon prevailing narratives of voyeurism, identity, and complicit shame explored by Hitchcock. Jeannine Oppewall, an Academy Award–nominated production designer for L.A. Confidential (featuring the Richard Neutra–designed Lovell House in its own villainous star turn), noted that in her line of work, “the best architecture [goes] to the film’s worst characters.”

Hitchcock manipulated our collective memory and the language of building design to create constructed expressions of human emotions, including love, envy, and the killer instinct. He was driven by an intense engagement with location and architectural form, picturing buildings not only as scenic devices but as interactive participants. For Hitchcock, the parts of a structure represent humanity and all its complications: Windows are the eyes into the soul, a stairway is a spine between the heart and mind, and a door permits entry into subliminal perceptions. His buildings—including the maternal Victorian mansion and naughty motel along the old highway in Psycho, the honeycomb of Greenwich Village apartments in Rear Window, the avian-infested Bodega Bay schoolhouse in The Birds, and the deadly skyscrapers and towers of Vertigo—illuminate the uncertain relationships we hold inside our own minds, with the built world around us, and between each other.