POSTED ON HIS INSTAGRAM PAGE EARLIER TODAY

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | January 2021 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

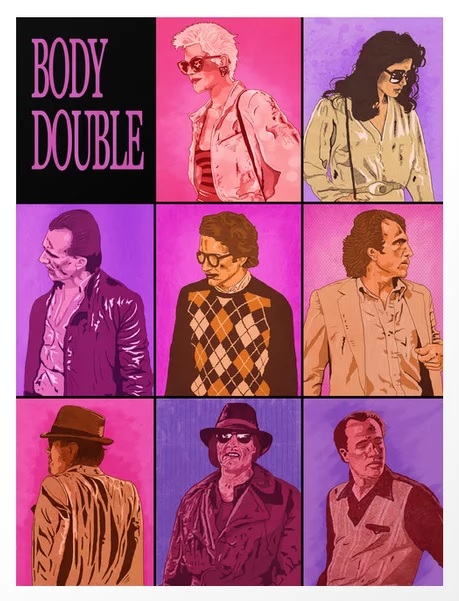

Meanwhile, earlier today, Collider's William Bibbiani posted a chronological list of "The 25 Best Psychological Thrillers of All Time." In his introduction, Bibbiani explains that there was "only one caveat: there’s only one film from each director, because some filmmakers make a cottage industry of this genre, and it’s important to share as many brilliant films from as many different perspectives as possible." And so when it came to Brian De Palma, Bibbiani chose Sisters:

Brian De Palma crafted the majority of his career around acrobatically photographed, labyrinthine psychological, and frequently sexual thrillers. But although Dressed to Kill, Obsession, Body Double and Raising Cain are all stellar, whirlwind shockers, it’s his first foray into Hitchcockian suspense that stands out. Sisters is a twisted, grotesque, unexpected delight.The story of Sisters takes many sharp turns, beginning with an amusing anecdote of voyeurism, segueing into young love and jealousy, careening into murder, and then returning once again to voyeurism. From there on out we’re in Nancy Drew territory, as a plucky young reporter, played by Jennifer Salt, investigating a murder she’s sure was committed by an aspiring actress, played by Superman’s Margot Kidder, or possibly her identical twin sister. That is, until De Palma’s Grand Guignol climax, where the rules go out the window and so does the mystery, as though the filmmaker couldn’t wait to show you just how disturbing and fascinating his imagination is.

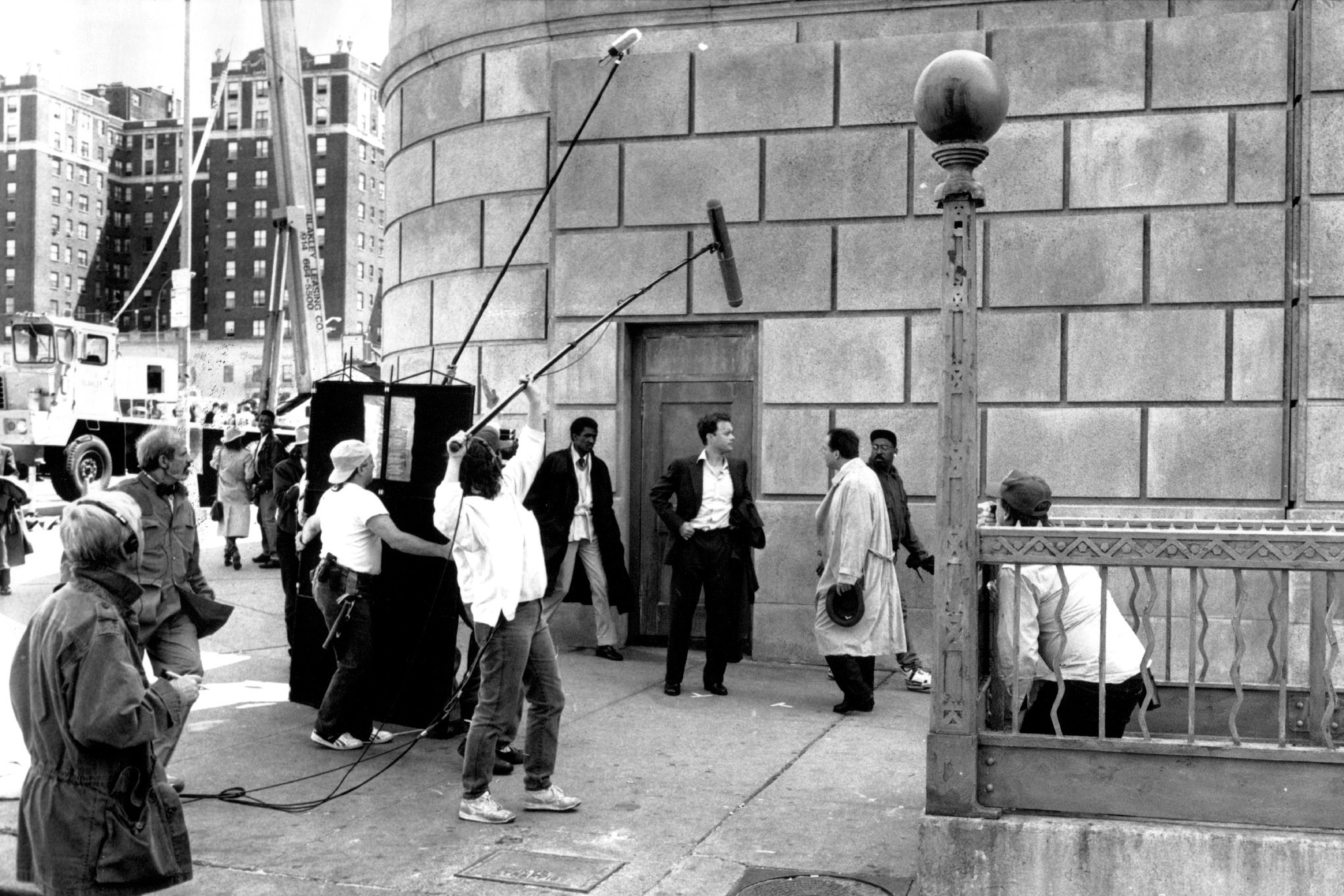

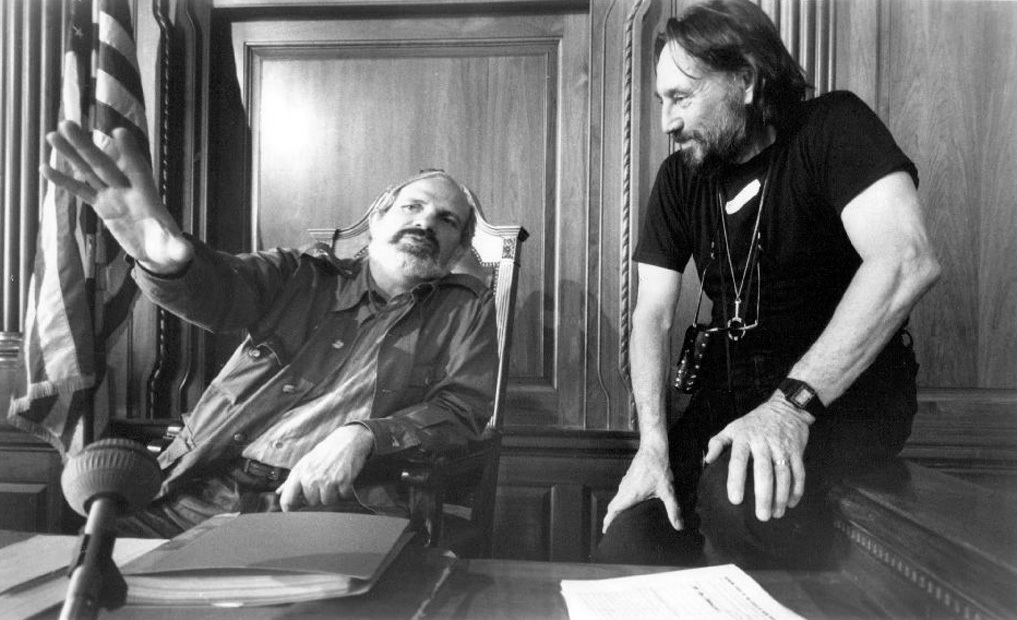

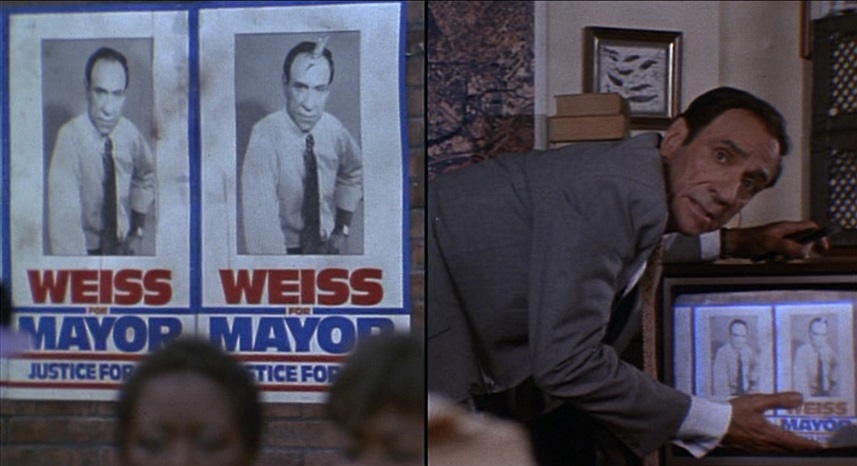

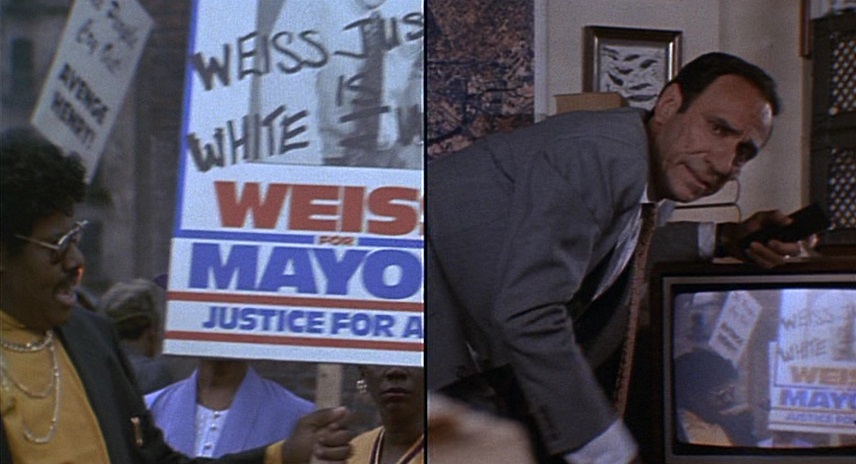

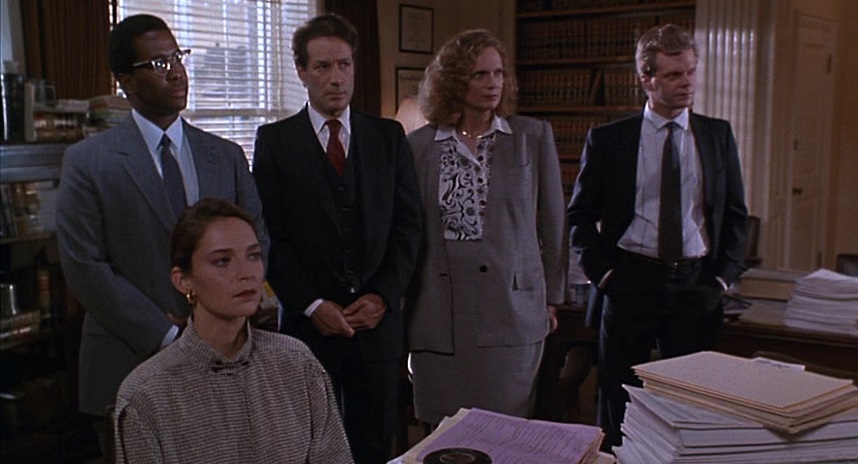

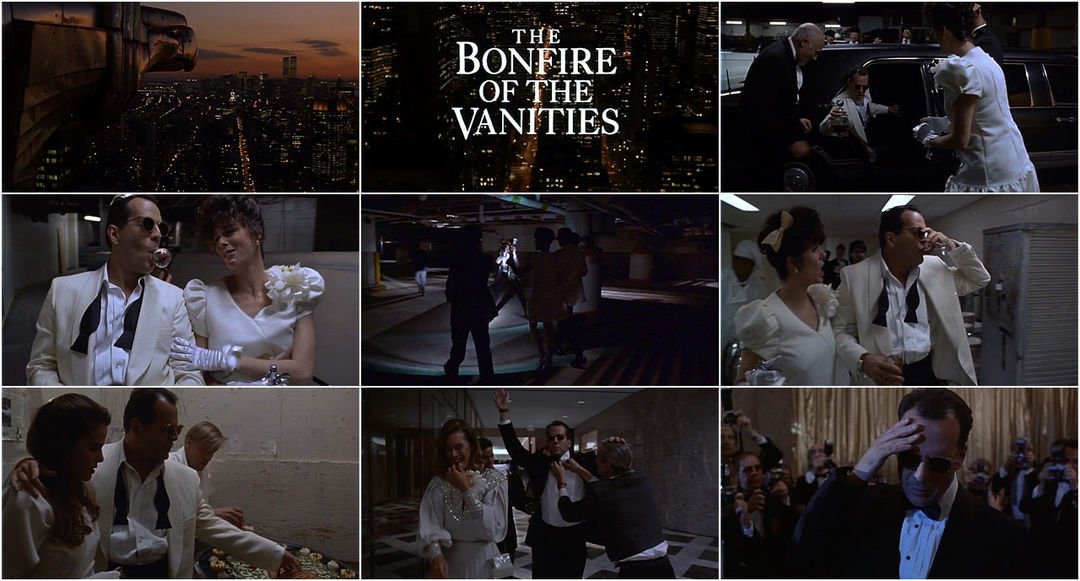

If you can somehow manage to remove all your memories and knowledge of the book from your mind—which was somewhat difficult back when the film first came out since it was pretty much the novel of its time—there is another and somewhat more interesting movie going on at the same time, and this is largely courtesy of the decision to have Brian De Palma direct. Then and now, he was most famous for his wildly audacious and often controversial suspense thrillers. The announcement that he would be doing “Bonfire” raised many eyebrows, with many assuming that he only got put on the list of potential directors because “The Untouchables” not only made a ton of money but proved that even an iconoclast like him could utilize his gifts to make an across-the-board blockbuster if he actually put his mind to it.However, before he became famous for making grisly and twisty thrillers, De Palma initially made a name for himself directing highly acerbic satirical comedies such as “Greetings,” “Hi Mom,” and his first studio effort, “Get to Know Your Rabbit.” These were films that took on the big issues of the time—race, sex, class, the war in Vietnam, the JFK assassination—and skewered them all in wild and oftentimes outrageous ways that not even the passing of the decades has managed to dim. (The only exception is “Get to Know Your Rabbit,” a film on which he feuded with star Tommy Smothers and was eventually fired by Warner Bros. marking the first and last time he worked there until “Bonfire” came along.) While those earlier movies, “Rabbit” excepted, were made on tiny budgets on the streets of New York and with largely unknown actors (including a pre-fame Robert De Niro), “Bonfire” allowed him the chance to return to those roots, albeit with tens of millions of dollars at his disposal this time around. Some of the funniest scenes in the film, such as the one in which Weiss insists to his staff that he is not at all racist while at the same time coming across as nothing but, could have easily come from those earlier films and also come the closest to hitting the edgy tone found in the original material.

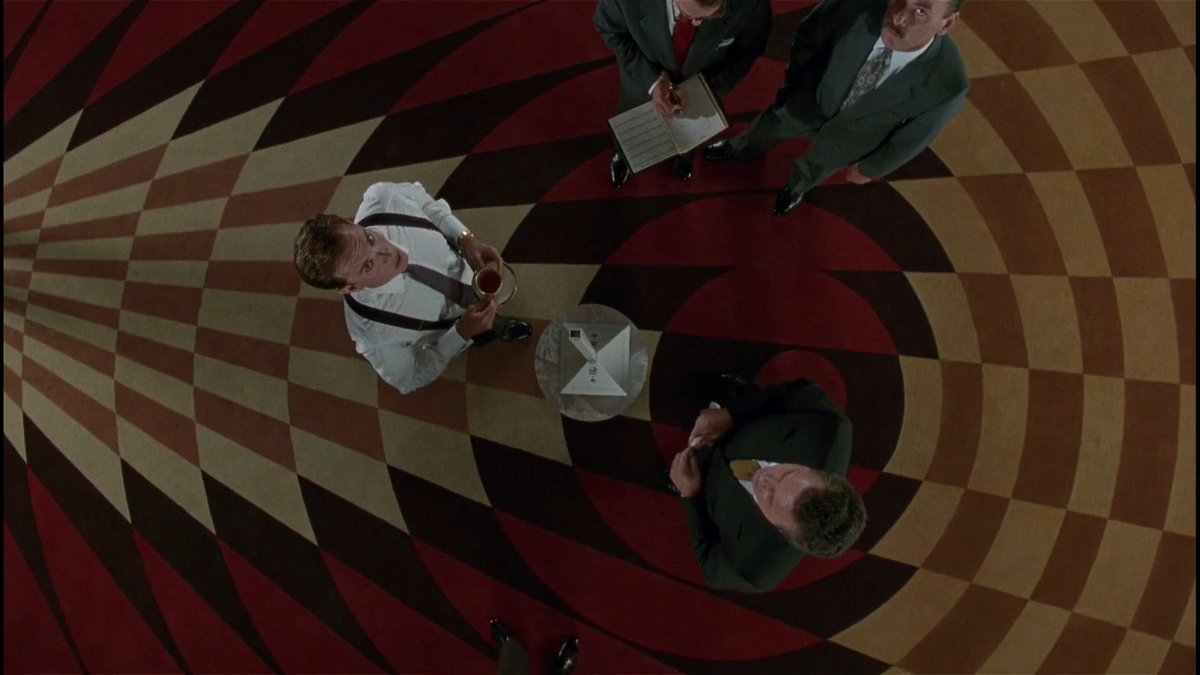

In bringing the story to the screen, De Palma, along with cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, utilized a highly stylized approach that favored the visual pyrotechnics for which he was famous. The film is full of elaborate camera moves (including an insanely intricate opening Steadicam shot of Fallow stumbling around backstage at a publishing party that runs for about five minutes without a cut) and weird closeups designed to make characters look even more grotesque than they already are. At the time, De Palma was criticized for employing such a seemingly unnecessary visual approach, but it actually fits the material. One of the key problems with anyone attempting to adapt Wolfe’s work to the screen is that it was his distinctive voice as a writer that made his work stand out so well, and it's that voice that's usually the first thing that gets lost during the adaptation process. While the screenplay awkwardly tries to invoke Wolfe’s prose by transforming it into narration from Fallow, De Palma’s visual gambits end up doing an unexpectedly effective job of finding a cinematic equivalent to Wolfe’s go-for-baroque literary style.

And while the film ultimately feels more like a collection of scenes from the book than a fully satisfying narrative, some of those scenes are quite good and entertaining. The opening Steadicam shot is, not surprisingly, a technical wonder but it also serves as an inventive introduction into the rarefied realm of the story, and Willis’ physical performance throughout the sequence is easily his most genuinely engaging bit in the film. The stuff involving the Weiss character is amusingly cynical and offers a real hint as to what the film might have been like had the material not been tamped down so much in an effort to make it more likable and accessible. And the scene in which Fallow has a fateful dinner with Arthur Ruskin is also quite funny, though I wish that it had gone on longer as it did in the book. Even the miscasting of Hanks winds up paying off nicely at one point late in the proceedings when he finds himself wrestling with the idea of lying in court about the origin of the fateful cassette—now that Hanks has long since established himself as contemporary cinema’s unquestioned patron saint of decency and moral uprightness, it's darkly funny to see him in a situation in which the only way for the truth to come out is to lie his ass off in court.

Considering how dated the once au courant material of "Bonfire" must seem to audiences today, the film's viewers are primarily those who have just finished reading The Devil’s Candy and are using it as a sort of visual guide to that book and not Wolfe’s. Hell, even when one looks at it solely on the basis of being a De Palma film, his most ardent supporters would be hard-pressed to put it in the top half or even the top two-thirds of his cinematic output to date. However, for all of its mistakes and miscalculations and moments of utter garishness (including one scene involving actress Beth Broderick and a photocopier that is almost astoundingly tasteless), "Bonfire" is not only more interesting than its reputation might suggest. In its best moments, the film demonstrates both a personality and a real live-wire charge, despite all of the efforts from above to eliminate such things from the proceedings. Those willing to look at it through fresh eyes and properly adjusted expectations may be surprised to discover it's not that bad after all.

Culp was assistant to Mr. De Palma on Snake Eyes (1998) and Mission To Mars (2000).

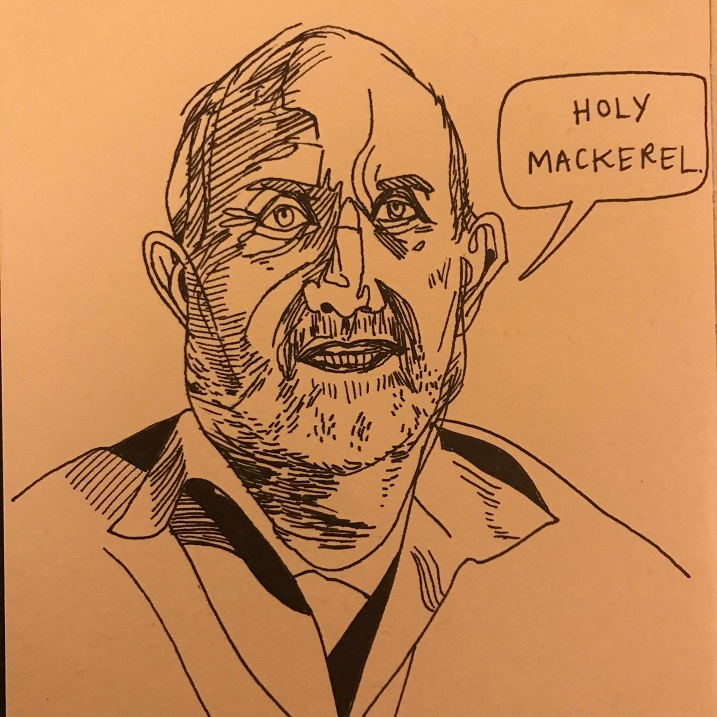

Merry Christmas! 🎄Here’s a portrait of director Brian De Palma that I drew while watching Noah Baumbach’s film “De Palma” about him on @mubi .

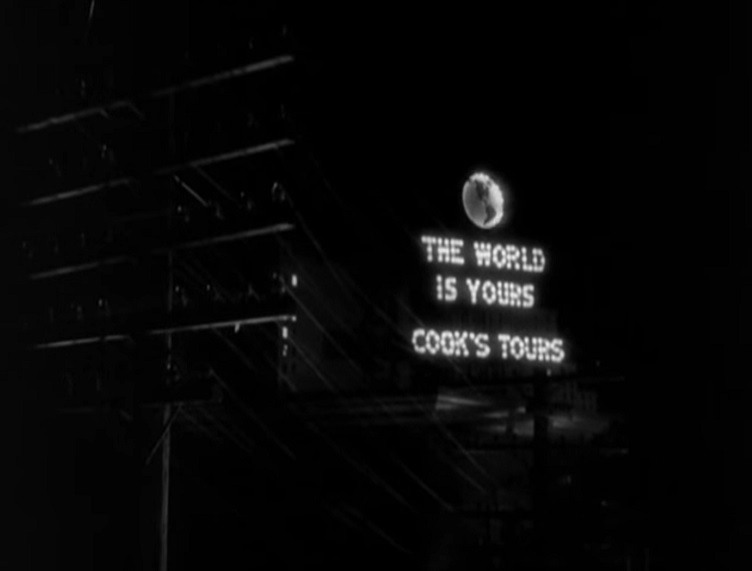

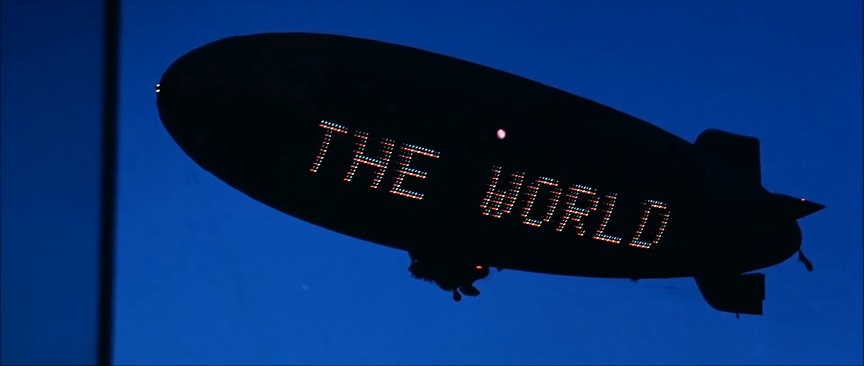

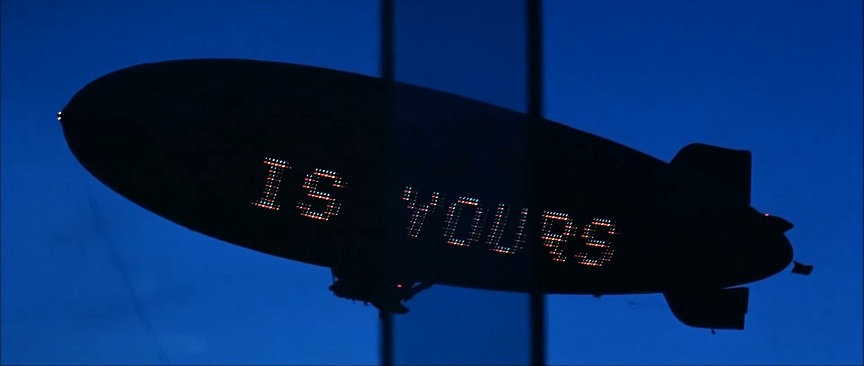

When Alonzo teamed up with De Palma in 1983 to shoot a remake of Scarface, the idea of a large electronic advertisement slogan, "The world is yours," was already a key moment in the original 1932 Howard Hawks version. To ask Alonzo to shoot that same slogan on a blimp about six years after shooting an ominous blimp for Frankenheimer's film is an in-joke that pays off, even if you don't get the reference, as one of the most memorable moments in De Palma's Scarface.

It is worth noting that the score for Black Sunday was composed by John Williams. The following year, Williams provided the propulsively dark music for De Palma's The Fury.

MEANWHILE, A FLASHBACK FROM 2004:

Posted April 13 2004

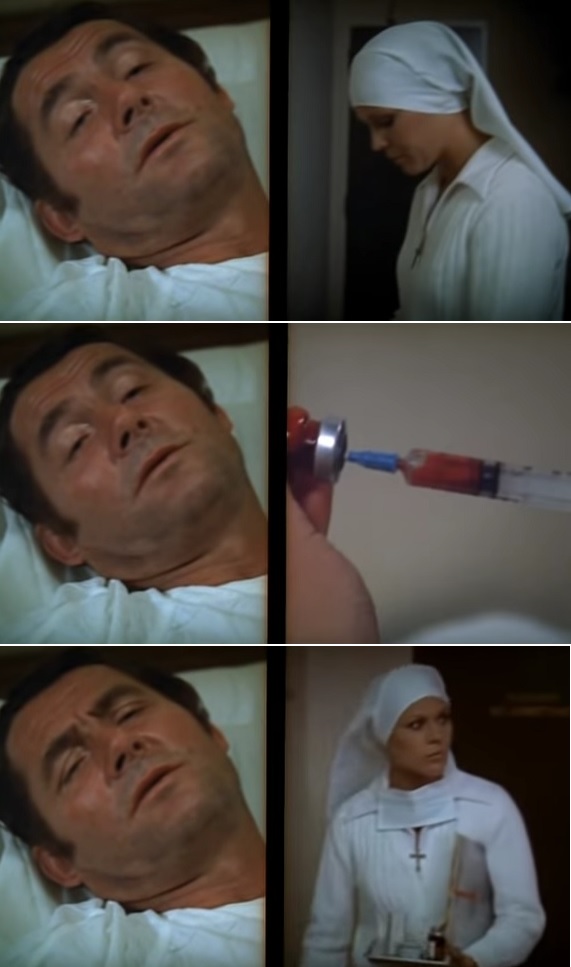

TARANTINO TALKS KILL BILL

EXPLAINS HIS "LITTLE BRIAN DE PALMA SCENE" It seemed logical that the split-screen sequence in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol. 1, where Daryl Hannah dons a nurse's uniform and whistles a Bernard Herrmann melody while carrying a deadly syringe down a hospital corridor, was inspired in great part by a combination of Brian De Palma's Sisters and Dressed To Kill. On the new DVD release of the film, Tarantino even calls it his "little Brian De Palma scene." But the filmmaker tells Premiere that this particular split-screen sequence was inspired by the trailer for a John Frankenheimer film-- a scene in the trailer that was cut and scored differently than it was in Frankenheimer's film. Tarantino explains that he does not duplicate other directors' shots when he references their films in his work, but rather "a feeling in the shot or an aspect about the shot I liked." He then explains how he has a collection of 35mm trailers from movies, particularly from the '70s, and how these trailers are works of art in and of themselves in that they used techniques that Tarantino likens to the work of Godard. Having seen the films that these trailers promote, Tarantino claims that many of the scenes or sequences shown in the trailers are not in the actual films. "It's just in the trailer," he tells Premiere:

It seemed logical that the split-screen sequence in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill Vol. 1, where Daryl Hannah dons a nurse's uniform and whistles a Bernard Herrmann melody while carrying a deadly syringe down a hospital corridor, was inspired in great part by a combination of Brian De Palma's Sisters and Dressed To Kill. On the new DVD release of the film, Tarantino even calls it his "little Brian De Palma scene." But the filmmaker tells Premiere that this particular split-screen sequence was inspired by the trailer for a John Frankenheimer film-- a scene in the trailer that was cut and scored differently than it was in Frankenheimer's film. Tarantino explains that he does not duplicate other directors' shots when he references their films in his work, but rather "a feeling in the shot or an aspect about the shot I liked." He then explains how he has a collection of 35mm trailers from movies, particularly from the '70s, and how these trailers are works of art in and of themselves in that they used techniques that Tarantino likens to the work of Godard. Having seen the films that these trailers promote, Tarantino claims that many of the scenes or sequences shown in the trailers are not in the actual films. "It's just in the trailer," he tells Premiere:

There's this one trailer for Black Sunday by John Frankenheimer that has a scene in it that's done differently than it is in the movie. It's amazing. There's a scene in the movie-- it's like, you know, killer terrorist shit-- where Marthe Keller is going to kill Robert Shaw, who works for the Israeli Army. He's in the hospital, so she dresses up like a nurse with a syringe full of lethal injection, and she's going to go into his hospital room and inject him. Well, in the movie it's an okay sequence, but not really that special. They don't really milk it that much. It's routine.

But in the trailer for the movie, when it gets to showing us that sequence, they do the whole thing in split screen. And where they just had natural sounds playing in the movie, they have John Williams's Black Sunday theme [humming the tune] pulsing through the whole trailer, so it's just ticking beats to the images. This is not in the movie anywhere. This is one of the best split-screen sequences I've ever seen.

So for Kill Bill, I say, "We're doing this when Elle Driver shows up at the hospital."

And then I have another, like, weird movie reference in there because I have Daryl Hannah whistling-- she learned how to whistle Bernard Herrmann's theme to this movie called Twisted Nerve. And the thing is, when she leaves the frame, the Bernard Herrmann score kicks in, you hear the same theme done in this lush Bernard Herrmann melody, and then it goes into split screen and it looks like I'm doing an homage to Dressed To Kill-era De Palma.

Bernard Herrmann scored two De Palma films: Sisters (1973) and Obsession (1976). Daryl Hannah made her film debut in De Palma's The Fury (1978), which was scored by John Williams. One character, Bobbi, steals a nurse's uniform to wear in De Palma's Dressed To Kill (1980). Sisters and Dressed To Kill each feature memorable split-screen sequences.

There is no author currently listed at that link of the Irish Times article, but it also delves into things that have been posted here at De Palma a la Mod recently, regarding how De Palma felt at that time, eight years removed, about The Bonfire Of The Vanities, Julie Salamon's book, and how "reviewers basically seem to review things with a herd mentality that flows through the press junket and what's in the press kit." Have a look:

The shrill, incessant whine of the fire alarm started at about four in the morning, and the evacuation of the Toronto hotel got underway. Moving briskly down the snaking fire escape from the sixth floor to the lobby, I recognised the grey-haired guest who was ahead of me - the American film-maker, Brian De Palma. We had met for an interview in New York just the week before.As we reached the ground floor and made our exit out into the chilly morning air, De Palma explained that he was in Toronto on a private visit, solely to watch movies at the city's annual film festival. Every year, he says, he goes to Toronto, and to the Montreal Film Festival which immediately precedes it, for his annual fix of international cinema, to catch all the many movies from around the world which fail to acquire cinema distribution, even in cosmopolitan New York where De Palma lives.

The great majority of film-makers attend festivals only when they have a new movie to screen, and even then, they whizz in and out, making the obligatory appearance at the premiere of their own movie and putting in a day or two of media interviews. The only other time I can recall a filmmaker spending any length of time watching other people's movies at a festival was the year Quentin Tarantino arrived in Cannes 10 days early for the world premiere of Pulp Fiction and spent all his time watching and talking about movies.

However, De Palma didn't even have a movie showing at Toronto; his latest film, Snake Eyes, was already playing in cinemas across he city. But then, De Palma is a cineaste - as is demonstrated by the cinematic references which abound in his work, some of which is like a shrine to Alfred Hitchcock, whose films he idolises.

Despite the market-driven, assembly-line philosophy which permeates the film industry, De Palma believes there is still a place for film as art today. "There are some very moving and artistic films being made," he said, "but they're certainly very much in the minority compared to what's in the mainstream."

Flashback to our New York interview a week earlier, and De Palma is in less positive humour, making no attempt to disguise his irritation at some of the reviews for his new film, Snake Eyes. The reviews have been "pretty mixed", he says. "But that's been happening to me since the beginning of my career," he adds. "People don't really seem to watch what's going on in front of the screen, and the reviewers basically seem to review things with a herd mentality that flows through the press junket and what's in the press kit."

"The European critics tend to be somewhat different. They're more likely to see what's there on the screen and review that. They seem to have more trained eyes in terms of what visually they respond to, and they're not caught up in the cliches of the media. I guess it's not a great era of great critics, but then again, it's not a great era of great cinema, either."

Nevertheless, the most negative reviews for Snake Eyes positively pale in comparison to the vitriolic response to De Palma's 1991 film of Tom Wolfe's The Bonfire of the Vanities, a project which attracted an extraordinarily intense level of media scrutiny before, during and after production.

Eight years on, De Palma shrugs dismissively at the memories of it all. "Again it's an example of people not seeing what's on the screen," he says. "They bring these preconceptions of what they think the movie should be and then criticise it harshly because of that. In Europe the film was better received because not so many people there had read the book. It was very much a book of its time. That happens. Some things tend to be very fashionable for a time, but they don't have the quality that makes them endure over the decades."

Now that he has more or less put all that flak behind him, De Palma says he has no regrets about allowing his friend, the then Wall Street Journal critic, Julie Salamon, such a breadth of access to observe and chronicle the making of The Bonfire of the Vanities in her book, The Devil's Candy, one of the most perceptive and illuminating books ever written on the film-making process and all its many problems engendered by corporate power, interference and compromise.

It is also a remarkably revealing book in terms of Brian De Palma himself, particularly in the chapter on his upbringing. "Perhaps it was inevitable," Salamon states, "that De Palma would end up in a high-profile, nasty competitive business like film-making, where one's accomplishments were judged publicly and often harshly - and a regular cycle of rejection and acceptance was an immutable fact of life."

He was born in Newark, New Jersey, and raised in Philadelphia, the third son of an orthopaedic surgeon and his wife. "Brian was a mistake," his mother, Vivienne, frankly tells Salamon in the book. "Brian was a surprise. I didn't really want to have another child. He was a premature baby. He weighed 4 lbs when he was born. I was in labour for three days, too. He just didn't want to be born. He would scream and scream. When he couldn't talk, he would scream. I think he had to do it. It was his way of asking for attention."

Long before he entered the highly competitive world of filmmaking, the young Brian De Palma was constantly competing with his older brothers, Bruce and Bart, for the attention of parents who never properly acknowledged his achievements. "His father attributed Bruce's achievements to his `brilliant mind'," Salamon states, while Brian succeeded, in his father's view, because he was "a contending individual".

Aspects of Brian's teenage life unavoidably re-surfaced in his work as a film-maker. At 17, suspecting his father of having an affair, he set about diligently taping all his father's telephone calls; in De Palma's riveting 1981 movie, Blow Out, John Travolta played a sound recordist who may or may not have witnessed a murder. And then there were the times when Brian's father would bring him along to watch him at work in the operating theatre - which goes some way towards explaining the almost casually blood-splattered nature of some of Brian De Palma's movies, especially his masterpiece, Carrie, in which blood is the unrelenting motif from startling start to shocking finish.

His new film, Snake Eyes, belongs with De Palma's cycle of cynical, paranoid thrillers which have included Blow Out and the 1968 Greetings. Snake Eyes takes place almost entirely within an Atlantic City gambling emporium and boxing arena where the US secretary of defence is shot during a prize fight.

Nicolas Cage plays the tainted local detective on the case, with Gary Sinise as his old friend, a navy commander now highly placed in the department of defence. Snake Eyes evokes Kurosawa's classic, Rashomon, in its viewing of the assassination from multiple perspectives - on a grand scale in this case, given that there are 14,000 witnesses and the complex is dotted with surveillance cameras.

Brian De Palma is one of those film-makers who emerged in the 1960s, along with Arthur Penn and John Frankenheimer, much of whose best work is indelibly marked by their disillusionment and cynicism in the aftermath of the John F. Kennedy assassination. De Palma was going on his first date with Jill Claybrugh, who co-starred with Robert De Niro in Greetings, on that fateful day in November 1963, when they saw television footage of the Kennedy assassination in a store window.

"The Kennedy assassination was probably the most investigated murder case in history," he says. "But the more you investigate the more murk you come up with." He cites the amateur footage shot by Abraham Zapruder in Dallas on the day. "The more you blow it up looking for hidden details, the harder it is to make out the picture."

The cynicism of Snake Eyes extends to the point where virtually every significant character in the movie is corrupt on one level or another. "That's the way people are these days," De Palma says matter-of-factly. So he believes that just about anyone can be bought these days? "Possibly," he says. "There doesn't seem to be anything morally wrong with it either. You just seem stupid if you don't take the money!"

He continues: "Having been brought up on the Jersey shore, I've watched Atlantic City evolve from a classy resort town to a casino world, which is a very unusual environment. There are no clocks or windows in the casinos. They represent a completely false reality. You walk into this place and all these lights and people smiling and handing you drinks. It looks like paradise. But in reality you're being robbed blind."

As one has come to expect from a Brian De Palma movie, technical virtuosity and visual style abound in Snake Eyes, most exhilaratingly in the opening 12 minute sequence which consists of one dazzling, apparently continuous steadicam shot following Nic Cage's nervy progress through the bustling boxing arena. "Well, it is cinema," De Palma says drily. "Catch the eye of the viewer and show them something on that big wide screen that uses the elements that are given to us to create these stories.

"I wanted to show the space it all happens in, to have the audience experience that blurred quick vision of what happens during the assassination. So much happens so fast that you have to propel it with a tremendous amount of energy so that they can't take everything in at first. And then you want the audience very much to want to go back to those various points of view to find out what they missed."

He pauses. "I don't take the easy way out."

If nothing else, The Bonfire of the Vanities does contain one of the most impressive — and most expensive — single shots in cinema history: a plane touching down at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport with the setting sun behind it. [Michael] Cristofer wrote a simple version of the scene into the screenplay, but it was second unit director Eric Schwab who brought it to glorious life on the big screen. Schwab himself volunteered for the seemingly thankless assignment, and made a $100 bet with De Palma that he’d come up with a shot so great, it would have to end up in the movie.Schwab’s first directorial decision was that the famed Concorde turbojet — which flew between Europe and America from 1969 until 2003 — was the only aircraft impressive enough to execute the shot he had in mind: an image of a plane touching down at the exact moment that the setting sun and the Empire State Building lined up in the same frame. After an enormous amount of preparation that included coordinating with the Concorde’s pilots and studying almanacs to determine the most favorable weather conditions, he eventually decided on June 12 as the date for his grand experiment.

That afternoon, he and his crew set up five cameras on the JFK tarmac preparing to film the arrival of the inbound Concorde flight. Each camera had only one role of film, and there wouldn’t be any second chances to get the shot. The plane took off 20 minutes prior to sunset, and for several frightening moments, Schwab was convinced they wouldn’t hit the runway at the designated time. At one point, his nerves got the better of him and he started filming a different plane as it came in for a landing.

But then, precisely on schedule, the Concorde descended, the sun and the Empire State Building were in perfect alignment and it was all captured on film. The final price tag? $80,000. But the feeling of having pulled off an impossible shot, and winning the $100 off of De Palma? Priceless.

The opening tracking shot was a very important way into the film. It took about 27 or 28 takes to get it right. The idea for the shot actually came from observing Truman Capote stumbling into parties completely drunk or drugged-up. I had been to a lot of those parties and I thought that’s how it should be for Bruce’s character: the voyage from the parking garage up through all the different strata of New York high society until his arrival at the huge palm garden of the World Trade Center. I started out making political comedies, caustic commentaries about the state of our society. The Bonfire of the Vanities felt like an extension of that. When I read the book I quite liked it. I thought it was an acerbic rendering of a particular madness going on in the ’80s. When I was adapting it I thought I should make the central banker character a little more sympathetic than he was in the book, and Tom [Hanks] was a good choice for that. But, of course, the film unnerved everybody because it wasn’t like the novel, which was, by then, a treasured icon of the New York literary scene. I changed things to make the film more palatable but they ended up upsetting a lot of people and it got very bad reviews. Looking back, I find it a very successful picture. It just isn’t the book.

Upon the film's 20th anniversary in 2010, screenwriter Michael Cristofer was asked by Movieline's Mike Ryan to speak about what went wrong with Bonfire:

Oh, it’s a very simple answer: When Brian De Palma and I were working on the script, Warner Brothers agreed that we would do a three-hour film. It was going to be a three-hour epic version of that book. I wrote a script that everyone around Hollywood and New York who read the script said that not only was it the best script that I had ever written, but it was one of the best screenplays ever written. And I say that humbly because it was Brian who really helped me a lot. I mean, we really worked closely on making that script. You know, he’s a genius. His IQ is like 160 or something. Really, it was a tough job and I had done a version of it and then Brian came on and then we really, really worked closely together. And he was storyboarding the whole script as we were writing it. I learned more about directing on that film then probably on any other film where I worked as a writer.And what happened was two things: Number one, Warner Brothers completely undermined Brian’s casting of the picture. I don’t remember who all of the people were meant to be. Tom [Hanks] was in, that was OK. But, you know, Bruce Willis, that part was supposed to be played by Michael Caine. There were other casting choices that Warner Brothers totally interfered with, and [the studio] threatened to throw Brian off of the picture if he didn’t comply.

And then, finally, like three weeks or two weeks before we started shooting, they gave us the news that the film had to be two hours. It had to be under two hours. So, what was a really terrific script, and what would have made probably a very good movie, ended up being edited down in the space of 48 hours. I mean, we just cut the sh*t out of the script. And, what happened, because of that, was it took on a kind of broader, cartoon sort of feel that just didn’t work. It just didn’t work. Because, you know, when you’ve got something that’s filled with detail and you take out all of the detail and make it shorter, it just got broader, broader, broader and broader.

I think that’s what did it: It was 180 pages of script that we had to cut down to like 110. And we didn’t have the time to do it. There was no time do it. You know, we didn’t have four or five weeks, we had to do it overnight. I’ve actually never read the book that Salamon wrote, The Devil’s Candy. I’ve actually never read it because I manged to avoid her during the entire shoot. [Laughs] So I know a lot of other stuff went on, but the basic problem, that was it, as far as I was concerned. I look at it now and I realize the script is ruined, so the movie is ruined.