KIESLOWSKI, BODY DOUBLE, MICHAEL KORESKY DISCUSSES FF IN FILM COMMENT COLUMN

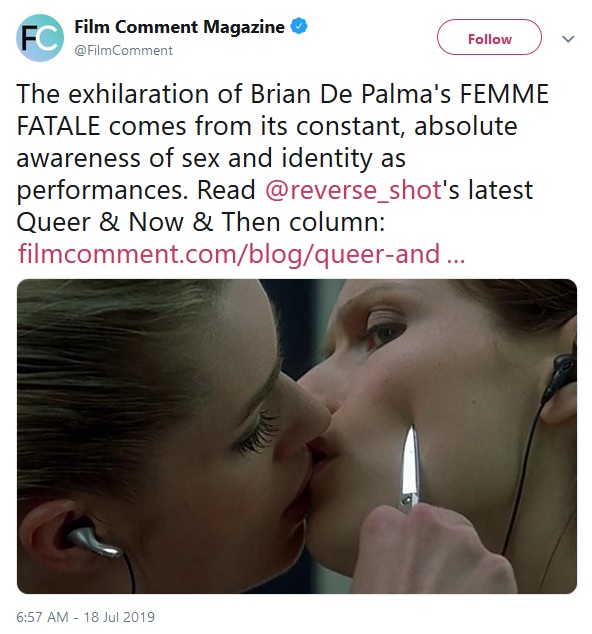

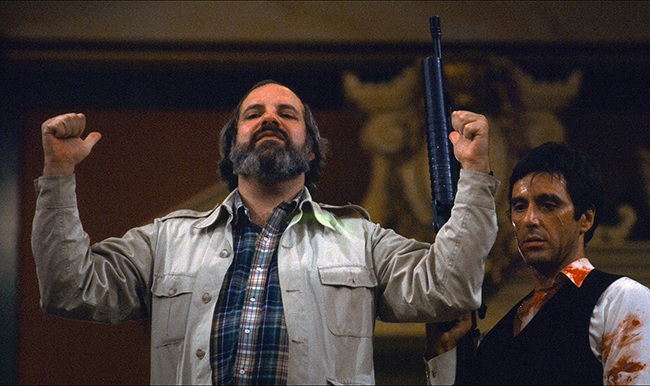

Michael Koresky's "Queer and Now and Then" column "looks back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface." Here's the first three paragraphs from his new essay on Brian De Palma's Femme Fatale:

For a director whose cinema would seem straight as a razor, Brian De Palma’s films radiate an undeniable queer energy. This unrepentant male gazer is perhaps an odd candidate for queer study, yet there are multiple avenues worth exploring that could help explain how De Palma has managed to penetrate the consciousness of many a gay viewer, this one included. I can name at least 10 gay-identifying critics off the top of my head who are entrenched fans, and I would argue that the intense appeal his films hold for us goes beyond visual voluptuousness or camp—though such matters are not incidental—and into a deeper, subconscious realm that rejects fixed identities, embraces marginalization, and acknowledges the integrity, even the necessity of social performance. De Palma’s dream states—and his dreams-within-dream states—are not merely alternate realities; they represent lives outside of normative functions. The false, bottomless narratives of some of his best thrillers—Sisters, Dressed to Kill, Body Double, Raising Cain, Femme Fatale, Passion—contribute to an outrageous kind of sensuousness that short-circuits cognitive, linear reality.Rare is the De Palma movie that prizes or reifies standards of normalcy, heterosexual or otherwise. There is a radical empathy at work, for instance, in Carrie (1976), which encourages identification with an ostensible “monster,” making it all but impossible to feel a deep, nearly spiritual connection to a mercilessly bullied outcast. Even Dressed to Kill (1980), a film that could easily be tagged as transphobic, functions on an emotional gut level primarily because it engenders sympathy for all of its main characters, each of whom is socially marginalized and thus in one way or another exists outside of traditional, progressive roles: Angie Dickinson’s sexually starved housewife, Nancy Allen’s persecuted sex worker, Keith Gordon’s lonely teen geek, and, most importantly, Michael Caine’s killer psychiatrist, whose trans identity, in the film’s crass, hothouse B-movie logic, is akin to a murderous split personality disorder, an extreme, R-rated riff on Norman Bates. Employing and slyly parodying Psycho’s psychiatric diagnosis, Dressed to Kill is an uncloseted, unbound film that exists at the intersection of various characters’—and viewers’—erotic fixations. Perspective is of paramount importance in De Palma’s films, not just because of the complex networks of who’s looking and who’s being looked at but also for the ways in which we are invited to experience desire right along with the people onscreen.

I’ve long found Femme Fatale to be De Palma’s queerest film, both for explicit narrative reasons and for something more connected to aesthetic perspective. The exhilaration of his 2002 thriller comes from its constant, absolute awareness of sex and identity as performances and the manner in which it unabashedly, knowingly lures the viewer into its world of luxurious game playing. In De Palma’s films, desire becomes spectacle, an unavoidable and somewhat serious extension of the director’s oft-reiterated belief that people go to the movies to watch women. “People have been looking at beautiful women since the beginning of time,” he shrugged to an interviewer at the time of Passion’s release in 2012. “All you have to do is look on your television screen or go Googling or pick up a magazine, and what do you see? Women, dressed or undressed. That’s what people are interested in.” He’s intractable on the point of visual pleasure and for decades has played enough variations on this theme to make it both persuasive and surprisingly rich. Femme Fatale doesn’t shift perspective away from De Palma’s fixations, but it so perversely and continually looks back at itself, refracting, shattering, and reconstituting its own gaze—and its characters’, and ours—that it effectively queers itself in the process.

Mark Kermode: "Although contemporary reviews were mixed, Obsession is now considered to be one of De Palma's finest."

Updated: Friday, July 19, 2019 8:10 AM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

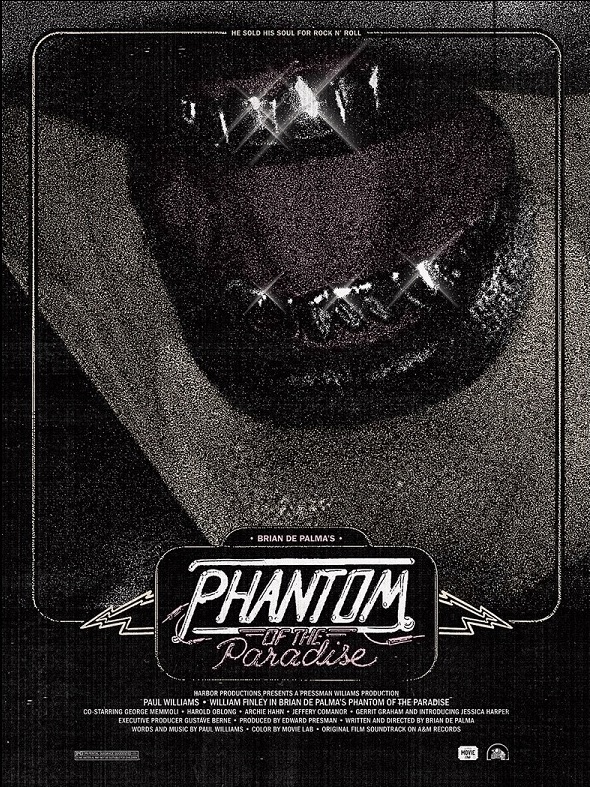

Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise will screen from a 35mm print at midnight Friday, July 19th, as part of the

Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise will screen from a 35mm print at midnight Friday, July 19th, as part of the  The

The