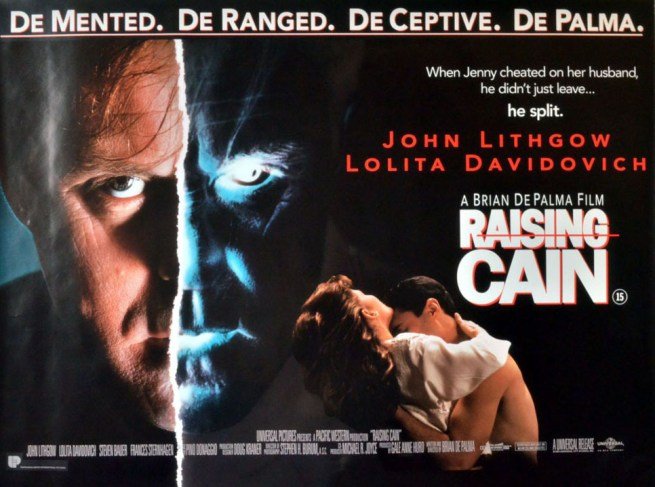

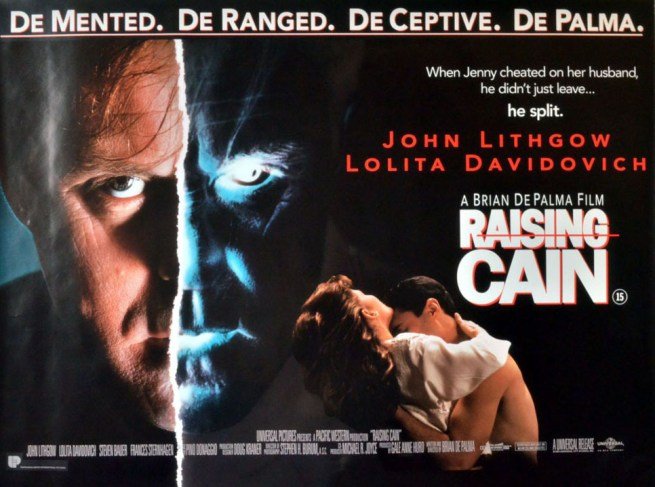

2 WRITERS DISCUSS STYLE & POLITICS OF 'RAISING CAIN'

AT ALCOHOLLYWOOD, LOOKS AT ORIGINAL THEATRICAL VERSION AS WELL AS THE RE-CUT

"In anticipation of

M. Night Shyamalan’s

Glass, two writers go back and forth on the style and politics of

Brian De Palma’s multiple-personality thriller

Raising Cain." Thus goes the introduction to

a post at AlcoHollywood from last week, with the headline, "Of Two Minds: Dissociating Ourselves from

Raising Cain." The two writers are

Gena Radcliffe and

Chris Ludovici, with the latter's words in italics, in order for the reader to differentiate between the two as they go back and forth.

"Brian De Palma’s movies aren’t about sense, they’re about emotions," Ludovici states early on. "His movies are visually opulent and voyeuristic, they’re about watching people do things, and what they do is betray one another. From his personal passion projects to his massive studio blockbusters the issue of trust and how it’s impossible appears again and again."

Looking at the original theatrical version of Raising Cain, Radcliffe states, "It’s rare to find a movie that would benefit from being longer, but Raising Cain could have used another twenty or even thirty minutes. It’s edited down to within an inch of its life so that the entire plot confusingly feels like it takes place on the same day. Key elements are explained rather than shown, and the characters are thinly drawn, verging on stereotypes — the wisecracking cops, the concerned best friend, the handsome love interest, the German-accented psychiatrist. Jenny is an aggressively off-putting 'heroine,' and all we really know about her is that she’s a doctor who had an affair with a dying patient’s husband, kissing him right in the hospital room. We don’t even really know much about Carter, other than he has multiple personalities, and is hyper-focused on his young daughter, in a way that could be unhealthy, but who can say for sure, because it’s never explored."

"MOSTLY JUST FOR THE HELL OF IT," SHE SAYS

Radcliffe later continues:

Still, it can’t be emphasized enough that John Lithgow makes a feast of his roles, playing sinister, sympathetic, campy, and compelling all at the same time. The scenes when Carter’s "twin” Cain mocks him are both funny and tragic, in a “Gollum looking at himself in the water” way. De Palma’s love of Hitchcock-style imagery serves this movie particularly well, a good reminder that you’re not watching anything that’s supposed to be a realistic depiction of DID. Raising Cain isn’t a bad movie, it’s just confounding, an interesting premise that needed more structure, and more fleshing out. And, as it turns out, there’s a twist in the making of the movie itself.

The strange pacing and editing were a last-minute decision for De Palma after the original cut tested poorly with audiences. Why anyone thought that a psychological thriller would work better if it was harder to follow is unknown, but that’s how it was released, much to De Palma’s regret. Twenty years after Raising Cain was released, a filmmaker from the Netherlands, mostly just for the hell of it, recut the film so that it more closely resembled the original script. Nothing was added or taken away, scenes were merely moved around so that the plot was somewhat more linear. The recut got back to De Palma, who was so pleased with it that he petitioned to have it added to the 2016 Blu-Ray release, claiming that it was the way the movie was always meant to be seen.

In the interest of good journalism (and because I had to see if it really did improve whatever the hell is supposed to be happening), I watched the recut, and you know what? It actually works pretty well. It opens with Jenny reconnecting with Jack, and her bizarre excitement over the prospect of cheating on her husband, which is reminiscent of Dressed to Kill, though she doesn’t pay for it in quite so gruesome a fashion as Angie Dickinson does in the earlier movie. The gauzily lit, soap operatic “lovers reunited” plot ends with a flashback of Jack’s terminally ill wife seeing them kiss and literally dying instantly, providing a delightfully effective bridge from romantic melodrama to psychological thriller.

After about the 45-minute mark, the “director’s cut” more or less follows the theatrical cut. While the movie still, in the end, doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, it no longer quite feels like being thrown into the deep end of a pool without a life preserver. Not having to focus so much on trying to figure out what’s happening (it’s safe to assume that probably about 45% of it is only occurring in Carter’s fractured mind) allows plenty of opportunity to really see just how great John Lithgow is. He’s not just sad and a little scary, he’s hilarious, abruptly changing his facial expressions from “evil” to “innocent” in some scenes like he’s a human Looney Tunes character. It’s obviously an intentional choice, and even better when compared to how straight all the other actors play their roles. Lithgow is at his best when playing perhaps the most dangerous personality, “Margo,” who says nothing, smiles sweetly, and headbutts old ladies; regrettably she doesn’t show up until the last fifteen minutes of the movie. If Raising Cain still feels too short, it’s simply because we don’t get enough of Lithgow taking a potentially touchy subject matter and brilliantly, gleefully, riding it into camp oblivion.

Meanwhile, interspersed with Radcliffe's words, Ludovici continues to describe the autobiographical aspects of De Palma's work:

There’s a war raging inside of Brian De Palma. As a child he won a regional science fair by building his own computer, he went to college to study physics before being seduced by filmmaking. His best films and sequences have an almost clockwork construction, they’re known for their long uninterrupted takes that suggest fascination but also distance. His movies are often simultaneously horrific and clinical in a way that suggest a bloodless, pitiless scientist running rats through a lethal maze. But that intelligent, scientifically minded child had a chaotic home. His father (a respected Philadelphia doctor) was a serial adulterer and the young De Palma followed him around and photograph him with various women, he even created a time-lapse camera so that he could stake various locations out without being there. Once, he threatened his father with a knife after ambushing him and one of his conquests at his office.

That tension between the thoughtful intellectual and the furious adolescent is the fuel that makes De Palma’s work go. And it changes the purpose of detached distance that he also seems to take from his subjects too. Maybe he doesn’t hold his subjects at arm’s length because he doesn’t care about what happens to them; maybe it’s because he doesn’t trust what he would do if he got too close.

At their core, his DID movies are about how, at the end of the day, we also can’t really trust ourselves. We might think we’re better and more knowledgeable than the people around us, but we’re not even safe from ourselves. There are no safe places in Brian De Palma’s world – not even inside our own minds.

Read the whole thing at

AlcoHollywood.

The staff at Brooklyn Vegan notes that the video for the new song by King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, Cyboogie, "pays homage to Brian De Palma’s 1974 cult favorite Phantom of the Paradise. The video was directed by Jason Galea.

The staff at Brooklyn Vegan notes that the video for the new song by King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, Cyboogie, "pays homage to Brian De Palma’s 1974 cult favorite Phantom of the Paradise. The video was directed by Jason Galea.

Piper De Palma, daughter of Brian De Palma, makes her feature film debut in Spiral Farm, which had its world premiere at the

Piper De Palma, daughter of Brian De Palma, makes her feature film debut in Spiral Farm, which had its world premiere at the

With a new movie (Vicky Jewson's Close) world premiering on Netflix yesterday,

With a new movie (Vicky Jewson's Close) world premiering on Netflix yesterday,

Saoirse Ronan discusses her new film, Mary Queen of Scots, in a profile piece written by

Saoirse Ronan discusses her new film, Mary Queen of Scots, in a profile piece written by