AS WELL AS THE FILM'S POLITICAL & CINEMATIC MELTING POT OF INSPIRATIONS

Updated: Sunday, April 15, 2018 8:14 AM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | April 2018 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Michiko Kakutani reviews James Comey's new book, A Higher Loyalty, for the New York Times:

Michiko Kakutani reviews James Comey's new book, A Higher Loyalty, for the New York Times:Comey is what Saul Bellow called a “first-class noticer.” He notices, for instance, “the soft white pouches under” Trump’s “expressionless blue eyes”; coyly observes that the president’s hands are smaller than his own “but did not seem unusually so”; and points out that he never saw Trump laugh — a sign, Comey suspects, of his “deep insecurity, his inability to be vulnerable or to risk himself by appreciating the humor of others, which, on reflection, is really very sad in a leader, and a little scary in a president.”During his Senate testimony last June, Comey was boy-scout polite (“Lordy, I hope there are tapes”) and somewhat elliptical in explaining why he decided to write detailed memos after each of his encounters with Trump (something he did not do with Presidents Obama or Bush), talking gingerly about “the nature of the person I was interacting with.” Here, however, Comey is blunt about what he thinks of the president, comparing Trump’s demand for loyalty over dinner to “Sammy the Bull’s Cosa Nostra induction ceremony — with Trump, in the role of the family boss, asking me if I have what it takes to be a ‘made man.’”

Throughout his tenure in the Bush and Obama administrations (he served as deputy attorney general under Bush, and was selected to lead the F.B.I. by Obama in 2013), Comey was known for his fierce, go-it-alone independence, and Trump’s behavior catalyzed his worst fears — that the president symbolically wanted the leaders of the law enforcement and national security agencies to come “forward and kiss the great man’s ring.” Comey was feeling unnerved from the moment he met Trump. In his recent book “Fire and Fury,” Michael Wolff wrote that Trump “invariably thought people found him irresistible,” and felt sure, early on, that “he could woo and flatter the F.B.I. director into positive feeling for him, if not outright submission” (in what the reader takes as yet another instance of the president’s inability to process reality or step beyond his own narcissistic delusions).

After he failed to get that submission and the Russia cloud continued to hover, Trump fired Comey; the following day he told Russian officials during a meeting in the Oval Office that firing the F.B.I. director — whom he called “a real nut job” — relieved “great pressure” on him. A week later, the Justice Department appointed Robert Mueller as special counsel overseeing the investigation into ties between the Trump campaign and Russia.

During Comey’s testimony, one senator observed that the often contradictory accounts that the president and former F.B.I. director gave of their one-on-one interactions came down to “Who should we believe?” As a prosecutor, Comey replied, he used to tell juries trying to evaluate a witness that “you can’t cherry-pick” — “You can’t say, ‘I like these things he said, but on this, he’s a dirty, rotten liar.’ You got to take it all together.”

Put the two men’s records, their reputations, even their respective books, side by side, and it’s hard to imagine two more polar opposites than Trump and Comey: They are as antipodean as the untethered, sybaritic Al Capone and the square, diligent G-man Eliot Ness in Brian De Palma’s 1987 movie “The Untouchables”; or the vengeful outlaw Frank Miller and Gary Cooper’s stoic, duty-driven marshal Will Kane in Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 classic “High Noon.”

One is an avatar of chaos with autocratic instincts and a resentment of the so-called “deep state” who has waged an assault on the institutions that uphold the Constitution.

The other is a straight-arrow bureaucrat, an apostle of order and the rule of law, whose reputation as a defender of the Constitution was indelibly shaped by his decision, one night in 2004, to rush to the hospital room of his boss, Attorney General John D. Ashcroft, to prevent Bush White House officials from persuading the ailing Ashcroft to reauthorize an N.S.A. surveillance program that members of the Justice Department believed violated the law.

One uses language incoherently on Twitter and in person, emitting a relentless stream of lies, insults, boasts, dog-whistles, divisive appeals to anger and fear, and attacks on institutions, individuals, companies, religions, countries, continents.

The other chooses his words carefully to make sure there is “no fuzz” to what he is saying, someone so self-conscious about his reputation as a person of integrity that when he gave his colleague James R. Clapper, then director of national intelligence, a tie decorated with little martini glasses, he made sure to tell him it was a regift from his brother-in-law.

One is an impulsive, utterly transactional narcissist who, so far in office, The Washington Post calculated, has made an average of six false or misleading claims a day; a winner-take-all bully with a nihilistic view of the world. “Be paranoid,” he advises in one of his own books. In another: “When somebody screws you, screw them back in spades.”

The other wrote his college thesis on religion and politics, embracing Reinhold Niebuhr’s argument that “the Christian must enter the political realm in some way” in order to pursue justice, which keeps “the strong from consuming the weak.”

Cannes Film Festival chief Thierry Frémaux said this morning that the finishing touches on the lineup announced today were honed until about 3 AM local time. It’s not unusual for him to go down to the wire, and there will be more titles announced in the coming weeks as the 71st edition of the venerable seaside shindig approaches. But what we got today was a mixed bag of new and familiar faces with a number of tipped movies not in the preliminary cut.The selection looks “light on paper” was a refrain I heard coming out of the press conference and throughout the day. But critics and longtime attendees cautioned there might be gems therein. For now, only the selection committee knows — though Frémaux said that none of the films they saw was completed.

Frémaux called the selection a “generational renewal.” There is a sense that some titles to be added could raise the pulse. We also hear a number of directors opted out of competition companion Un Certain Regard to look toward Directors’ Fortnight, which has been reinvigorated in recent years under exiting chief Edouard Waintrop. The Fortnight (which is not an official Cannes section) and Critics’ Week announce next week.

Adam Nayman at The Ringer yesterday posted "What’s Streaming: The Wild World of Brian De Palma," highlighting four De Palma features that are currently streaming at various websites: the "weirdly profound" Sisters (on Filmstruck), Carrie (on Amazon Prime), Scarface (on Netflix), and Passion (Amazon Prime).

Adam Nayman at The Ringer yesterday posted "What’s Streaming: The Wild World of Brian De Palma," highlighting four De Palma features that are currently streaming at various websites: the "weirdly profound" Sisters (on Filmstruck), Carrie (on Amazon Prime), Scarface (on Netflix), and Passion (Amazon Prime).Regarding Scarface, Nayman contrasts it with and favors it over The Untouchables, which is the movie ranked by the EMPIRE podcast the other day as De Palma's best:

In the 1980s, De Palma switched genres from stylized, Westernized giallos to muscular riffs on gangster pictures. The unofficial trilogy of Scarface, Wise Guys, and The Untouchables reached back to the classic crime films of the 1930s. Scarface was literally a remake of Howard Hawks’s veiled 1932 Al Capone biopic of the same name; working with screenwriter Oliver Stone, De Palma updated Hawks’s template for the vicious, me-first mentality of the Reagan era, reimagining the main character as a Cuban immigrant who begins the film by denouncing his country’s embrace of communism before turning into a ruthless, bloated, coked-out avatar of capitalistic excess. As usual with De Palma, it’s hard to tell how seriously we’re supposed to take this extravagantly violent film, its moralistic crime-pays-until-it-doesn’t messaging, or Al Pacino’s borderline-minstrel-show acting and accent. I’ve always felt that while the Stone(d) script meant every profane, Quaalude-driven word about the hypocritical futility of Captain Ron’s War on Drugs (as well as the revelation that the true holy trinity underneath the American Dream was not life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness but money, power, and women), De Palma was flat-out spoofing his antihero’s materialistic mentality—not to mention the idea of studio blockbusters, to the point that he actually got his old friend/industry overlord Steven Spielberg to direct part of the film’s cranked-up action climax. Reviled upon its release, Scarface has become one of the true cult-movie monoliths of its era, casting a long shadow over hip-hop culture and also its director’s subsequent work; a few years later, The Untouchables made more money and won Sean Connery an Oscar, but it can’t compare to its predecessor’s ugly, incandescent spectacle.

To the untrained eye, De Palma’s most recent effort—a remake of the disposable French trifle Love Crime starring Rachel McAdams and Noomi Rapace as coworkers turned rivals—is a strained, ridiculous mess. And that’s what it looks like to the trained eye, too: At times, it’s as if Passion is a parody of a modestly sleazy direct-to-video thriller rather than a late work by a great stylist. But no less than Sisters (which is referenced in a mid-film revelation about identical twins), the film’s ripe cheesiness has a whiff of satire to it. From the appearance of the credit “written and directed by Brian De Palma” overlaid on the sleek outer casing of an Apple MacBook Pro to a shot of a car driving into and destroying a parking-lot Coca-Cola machine, there’s a through line of anticorporate humor that juxtaposes the ideas of “art” and “product”—never more so than in an amazing, extended split-screen scene in which footage of a ballet performance competes for our attention with a knowingly clichéd, Halloween-style slasher-on-the-loose set piece. In the end, Passion might not be much more than a glib, embittered bit of gamesmanship by somebody who’s pretty much been on the sidelines since the mid-’90s, but there’s something sort of sweet about seeing its maker continuing to play by his own rules.

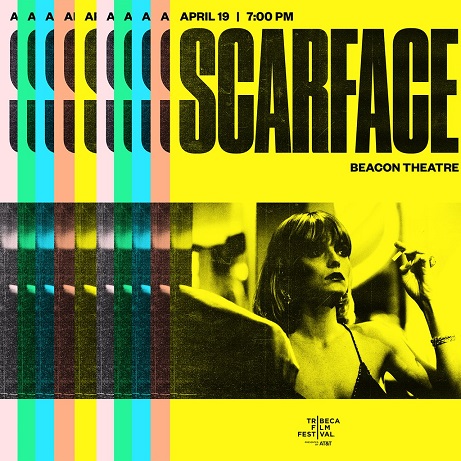

Steven Bauer will join Brian De Palma, Al Pacino, and Michelle Pfeiffer for an on-stage conversation following the Tribeca Film Festival's 35th anniversary screening of Scarface at the Beacon Theatre in New York on April 19th. In the time since the event was first announced back in March, a Tribeca Film Guide has popped up that describes the Scarface screening as a "World Premiere Restoration."

Steven Bauer will join Brian De Palma, Al Pacino, and Michelle Pfeiffer for an on-stage conversation following the Tribeca Film Festival's 35th anniversary screening of Scarface at the Beacon Theatre in New York on April 19th. In the time since the event was first announced back in March, a Tribeca Film Guide has popped up that describes the Scarface screening as a "World Premiere Restoration."

We used a special camera to do this. We actually used, like, a digital camera that has a smaller sensor, so we could get the depth of field for that shot. And then, this little bit right here was really fun to cut together, and to kind of... um... on set, I would say, We're gonna De Palma this moment. We're gonna stretch it out, kind of to a ridiculous degree, and do these slow motion shots where we stretch this moment of her trying to kick that thing down. And then when it actually falls, it was a question of just how long can we stretch this out for, and we kept pushing it and pushing it, and eventually hit a place where it's like, okay, this is the moment.

One of them makes a case for Mission: Impossible that the others make fun of him for, one of them tries to tell the others that Scarface is not thought of as anything great except by rappers and footballers, and there is disagreement about Phantom Of The Paradise, but there is also a lot that the four guys on this podcast agree on regarding Brian De Palma. Here's the introduction from EmpireOnline:

One of them makes a case for Mission: Impossible that the others make fun of him for, one of them tries to tell the others that Scarface is not thought of as anything great except by rappers and footballers, and there is disagreement about Phantom Of The Paradise, but there is also a lot that the four guys on this podcast agree on regarding Brian De Palma. Here's the introduction from EmpireOnline:The latest episode of The Ranking — our show that ties in with the magazine (hashtag brand synergy) and sees four Empire writers argue the toss on a filmmaker's CV — is here. And this time we're delving deep into the work of a man who's orchestrated more tracking shots than you've had hot dinners: Brian 'Bri Bri' De Palma.Discussing his progression from early promise to his virtuoso Hitchcockian phase and then the more commercial fare of the Eighties and Nineties (but without focusing on the not-so-great output of recent years), Chris Hewitt, Ian Freer, Nick de Semlyen and Jonathan Pile discuss the ins and outs, ups and downs of a great, if somewhat erratic career. And, for the first time, you'll be able to hear the top ten being counted down in this podcast. Give it a listen on Soundcloud, Planet Radio, or your podcast app of choice.

This isn't the only Empire Podcast dropping this week — in fact, we have a new episode arriving every day. Yesterday was an interview special with Rian Johnson and Mark Hamill, and still to come are Spoiler Special episodes on A Quiet Place and Ready Player One, ahead of Friday's regular pod. Enjoy.

Enough squabbling, let's vote! (Stop trying to make 'enough squabbling, let's vote!' happen, Chris.)

In any case, at least a couple of the reviews wish that De Palma had remained the director of the project, which was eventually made under the direction of Barry Levinson. Here's an excerpt from Vishnevetsky's review:

In other words, this isn’t what one would call an elegantly coordinated narrative. Making a secondary protagonist out of Sara Ganim (Riley Keough), who won a Pulitzer for her work on the charges against Sandusky and Penn State for The Patriot-News of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, might seem like a no-brainer straight out of Screenwriting 101. But Debora Cahn and John C. Richards’ amateurish script opts to just have random characters shout exposition at the journalist (“Joe Pa made an ethos in this whole place!”), as though she were having the scandal reported to her instead of reporting on it. Bewilderingly, the question of whether Paterno knew about accusations that Sandusky was molesting young boys (he did, since at least the late 1990s) and helped sweep said accusations under the rug (of course he did) are placed at the center of the film, when it’s clear that the more interesting question is “Why?” A drama about sexual abuse and institutional corruption might seem topical, but all Paterno offers its audience is a chance to re-experience the cable news cycle of yesteryear.Writing aside, Pacino’s Paterno is an intriguingly slumpy, sluggish, distracted figure. Having also played the title role in HBO’s David Mamet-directed Phil Spector, the actor is as much of an old hand at these things as Levinson, and he avoids bluster, instead stretching the raspy and burpy notes in his voice, playing the disgraced coach as a man confused by his own downfall. In fact, there are enough quality performances in Paterno—most notably from Greg Grunberg as Paterno’s son, Scott, and from Kathy Baker, who has a smaller role as the coach’s wife, Sue—to make one wish there were a better film to support them. One can’t help but play shoulda-woulda-coulda with the fact that Paterno began life as a reunion project for Pacino and his Scarface and Carlito’s Way director, Brian De Palma—by most accounts a very different film that would have focused on the relationship between Paterno and Sandusky. At the time, John Carroll Lynch was cast as the latter; in Paterno, the character is basically a non-speaking role, played by a jobbing actor named Jim Johnson, whose IMDB page offers a Tobias Fünke-esque collection of headshots.

To say that Levinson lacks formal chops of someone like De Palma would be an understatement. Enlisting the Hungarian cinematographer Marcell Rév (White God), he directs in the style that has increasingly come to pass for “creativity” in our age of prestige TV—that is, randomly placed wide-angle lenses and gelatinously shallow depth-of-field that presumably symbolizes the myopia of the characters, but mostly looks like the work of a film student who just got their hands on a T1.3 aperture for the first time. These entry-level distancing effects (see also: the MRI machine) never succeed in hiding or overcoming Paterno’s flimsiness as drama, its tendency to pass off the obvious as revelation. Is there a dark side to every success story? Probably. But the only cogent insight about society at large to emerge from HBO’s ongoing project to turn every fall from grace that makes the news for more than a week into a TV movie is the fact that there remains no shortage of material.

Watching HBO Films’ latest snatched-from-the-headlines project, “Paterno,” one can’t help but wonder how different it might have been had Brian De Palma directed it.He’s had an advantageous working relationship with star Al Pacino on both “Scarface” and “Carlito’s Way.” In his hands, the film could have been a “King Lear”-level tragedy about a sports legend whose singular focus led to his downfall.

Instead what viewers get is director Barry Levinson’s well-intended but paroxysmal journey into legendary college football coach Joe Paterno’s fall from grace, fired by Penn State for his role in the Jerry Sandusky abuse scandal.

Unsure if he wants to focus more on Paterno or newspaper journalist Sara Ganim — the reporter who broke the Sandusky story — Levinson constantly switches his gaze from one to the other. Ganim’s role as a consultant on the film may have mucked up the process even more. The end result is a film that clumsily tries to sympathize with Paterno instead of the young boys he chose to ignore until it was too late.

Brian De Palma’s 1981 political thriller Blow Out was the first movie that dared address the events conjured by the single term "Chappaquiddick.” It was a generational provocation. De Palma, whose comedies Greetings, Phantom of the Paradise, and Hi, Mom! were obsessed with the JFK assassination, advanced to make a deeply emotional film reenacting a well-known loss of life (a supposedly disposable female victim played by Nancy Allen) and national disillusionment. De Palma raised that tragedy, involving both a callous political cover-up and society’s general naïveté, into larger concerns: Blow Out’s daring aesthetic examination of a film technician’s (John Travolta) cinematic-moral process that also expressed modern American despair. Blow Out is an overwhelming movie experience, a would-be classic if it weren’t all but ignored by today’s largely unprincipled film culture.That’s why John Curran’s less flamboyant, more realistic approach in Chappaquiddick is such a moving surprise. Curran modestly takes on the historical events of the evening in 1969 when political campaigner Mary Jo Kopechne died in a submerged car, after Ted Kennedy accidentally drove the vehicle into the ocean. De Palma reimagined those incidents (including the cultural aftershock) with a combination of dreamlike intensity and paranoia. But Curran goes directly for the morally complex legend of the Massachusetts scion, to show how this political figure compromised himself.

In terms of both film and political history, Chappaquiddick is also a classic. Curran (and screenwriters Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan) break away from the Kennedy legacy so beloved by mainstream media. But these filmmakers also oppose the Millennial tendency toward demonization. Maybe every media consumer should see this film to appreciate the humanity that Curran and company display. They commemorate Kopechne (Kate Mara’s performance blends simple sweetness and cagey ambition) and sympathize with Kennedy — balancing the motives of both follower and icon. This is the rare occasion when partisan animus is ignored to facilitate an understanding of human culpability. The movie doesn’t exonerate Kennedy, but it challenges viewers to ease off their judgmental reflex.

The cynical smartness that has afflicted contemporary journalism and made much recent cinema insufferable is confronted by Curran’s conscientious dramatic rigor. Condemning someone you disagree with has become the rage since the 2016 election, as too many people seek to justify their own prejudices and power, the nation be damned. Upon reflection, De Palma’s shot of Nancy Allen screaming before the backdrop of a defamed Old Glory may be the single movie image that is sufficiently magnificent and full of dread to sum up our political and emotional crisis. Chappaquiddick extends the irony of that image in its tale of a politician twisted by his damaged ego and the burden of responsibility.