I talked to Michael Mann last year about Heat and he said something interesting contrasting the way you and De Niro approached your parts. He said De Niro would be the guy who asked a lot of analytical questions about his part and about his motivations, but that you just absorbed the scene weeks in advance and had it bouncing around in your head as a way of building out the character. Does that sound right? Yes, at times, because I work relative to what is around me. The role, the amount of time, what I’m doing, who I’m doing it with. I really like to approach roles, if I can, alone. It’s almost like writing about the character. Consuming it. I used to say “channeling it.” But I require more rehearsal than I usually get, and so I have to figure out how to cope with that. The thing I remember with Heat is saying, “Well, what are these mood changes the character has?” I thought, “All right, he chips cocaine, this guy.” And it turns out he did! Every once in a while I’d ask Mike, “Could you shoot something?” Because the audience doesn’t know he’s chipping cocaine like a nut, and they’re thinking, “What’s the matter with him?” And so we even shot something. But it’s not in the film. So, sometimes I look a little irrational. But that’s the source I used. I thought it added a kind of interesting texture to a cop.

In a lot of your earlier parts there is a kind of understated quality — the characters are very watchful, always absorbing things. In later years, you’re unafraid to go big, to at times be almost theatrical. Was that a conscious decision, or an evolution?

I think sometimes I went there because I see myself kind of like a tenor. And a tenor needs to hit those high notes once in a while. Even if they’re wrong. So sometimes they’re way off. There’s a couple of roles that, you know, the needle screeched on the record. But if I ever see a movie that I feel, “Oh, gee, I went too far,” I just fast-forward it a bit and move on. [Laughs] If I had to do it again…I don’t know, I might still do it that way. I think what happens is once you do it one or two times, it becomes a signature.

In Scarface, for instance. Brian [De Palma] said right at the start, “This is an opera, and this is what we’re gonna go for. This is not down-and-dirty realism.” And we called it Brechtian. That’s what we went for. Oliver Stone allowed for that in his conception and writing of the script. I saw that character as bigger than life; I didn’t see him as three-dimensional. It’s like, you know, Icarus and the sun; I saw him fly with that thing. That was the dynamic of Tony Montana that we went for.

When I saw Paul Muni do the original Scarface, I only wanted to do one thing and that’s imitate him. And of course my performance is not at all like what he did, but I think I was more inspired by that performance than any I have seen. I called Marty Bregman after I saw it, and said, “Marty, I think we should try to redo Scarface. Howard Hawks of all people!” And of course he got Lumet, who came up with that great idea of having him come in on the boat lift — a Cuban refugee. That broke the ice. Oliver went in there and wrote that script. Then somehow Lumet and Marty Bregman didn’t agree on the way to go with the film, so Brian did it. And he did a great job.

When [the Quad] offered me this [retrospective], I thought, if we’re going to do this, I would rather it be a lot of roles that are different — including roles that I sort of failed in. That’s sort of what it’s about: You’re seeing an actor’s struggle, and getting there and not getting there. An actor isn’t even aware that that’s happening. Because you take each thing on, hopefully, like it’s the very first thing you ever did.

There are a number of films in this retro that weren’t well-received when they came out. I’ve always quite liked Revolution, which was a huge dud.

It was absolutely destroyed. There are people who have throughout the years known what Hugh Hudson did in that film — some of the work he did in that as a filmmaker is just simply extraordinary. We stopped filming six weeks too early, and we should have gone back. At the same time, I said, “Hugh, I think there’s a step to be made here.” And for twenty years we kept trying to communicate and get together. We wrote a narration, which is in the film now. We spent money to do that. They cut a little more out, too, I guess. It all seems to help the film; it lifted it.

There’s another thing about certain films that didn’t work. I don’t like to look at them again, but when I watch them in retrospect, sometimes I’ll see something interesting. I was never a big fan of Scarecrow, for some reason. I don’t know why, at that particular time. And probably I don’t know still if I’m a fan of it or not. I haven’t seen it all. But Quentin [Tarantino] has this theater where he shows different movies from different eras, all in 35mm. To me, that’s the test: 35mm. He says, “Al, take a look at this. Come, take a look at Scarecrow.” I said, “Well, you know…” I was reluctant to see it. But he said, wisely, “See the first five minutes, Al. Just look at the first five minutes.” Well, I went and I saw the first five minutes, and it was…a revelation. Because you have Vilmos Zsigmond, you have Jerry Schatzberg, together. Two great photographers, working on a location. And that opening on 35 is shocking! Jerry Schatzberg gets these two guys in that five-minute span to connect when they absolutely are opposite ends of the world.

We have something here in this country that everything should work. Well, I don’t believe in that. I really think there are aspects in film sometimes that in and of themselves work, and are worth going to see. I had an old European guy once tell me that. “You know, Americans have this thing with film that it’s gotta work, and what does that mean? It always works for you — a film that works for you doesn’t work for me, works for someone else, though.” But when you see a moment that is captivating…well, it’s worth it, isn’t it? You don’t look at someone’s fifty paintings. You look at the painting! One painting! That’s enough.

Another film in this series that I’m excited to see on a big screen is Bobby Deerfield, which is a gorgeous movie, but which was also considered a disappointment.

Yeah, well, I wasn’t a big fan of that. I saw it a hundred years ago, didn’t want to see it again, naturally. And then one day a couple of years ago, I was sitting in my house and it came on, and I watched it. And it is imperfect, of course — but ultimately, it got me. Because so much of the film is the time. You perceive things because of what’s around you; that’s part of our game. What I responded to in Bobby Deerfield is that in it, you saw something revealed in this character, low-key — something I was going through in my life at that time. It wasn’t a performance that was coming at you, but it was something personal, and it showed. I saw it on a TV set, in the intimacy of my home, so perhaps that had something to do with it, and so many years had passed, and the memories of it — it was revealing. Maybe on the big screen it won’t work. But I figured, you know, show the ones that didn’t work, too. You can see the effort, and the contrast. But then there’s the roles that do come along once in a while where you say, “Oh, gee, I want to do this. I want to paint this. I want to express myself through this role.” That’s the luxury. That’s when you’re lucky.

What are some parts over the years that felt like that?

They come once in a while. I had it with The Indian Wants the Bronx, one of the first things I did Off-Broadway, and a really fortunate debut for me. A big step in my life, and certainly in what they call a “career.” Because I didn’t even know what a career was when I was in the Village in the old days. I just didn’t even think about it. I thought, “Where’s the paint, where’s the canvas?” That was what was in the air, in the streets, in the cafes that we performed in. You do sixteen shows a week, so you’re getting practice. Hopefully by the end of the sixteen, you know a little bit more than you did with the first show. That’s been my mantra: Just keep doing it. But I certainly remember feeling a certain expression when I did Pavlo Hummel, which I did in ’77, ’78. I felt it there. My roles in film, I certainly felt it in Scarface — that I was speaking to something. I was thinking just the other day, there’s a performance and then there’s a portrayal, and there’s a difference. When you finally get a certain thing, it becomes a portrayal. The others sometimes fall into the category of performance. But mostly what you’re always trying to do is get to the personal — because that’s what art is. It’s got something to do with how you feel about what you’re doing.

So many of your films have been genre movies: a cop thriller, a gangster movie, whatever. Take a movie like Sea of Love, which has a fairly conventional, predictable mystery structure, but you and Ellen Barkin completely transform it. By the end, we’ve been through this intense emotional experience. That’s something few actors can do on a regular basis.

I guess when you look at the roles objectively, you can see how different they are from each other. So, probably the guy in Sea of Love is different than the guy in Heat, or the guy in Insomnia. And then when you look at the gangsters, from Michael Corleone to Tony Montana, they may be in the same genre but they’re different. I know that I’ve consciously tried to separate the two. I try to find the difference in characters. Like Lefty in Donnie Brasco is different than Carlito in Carlito’s Way.

But there’s a four-year break between Revolution and when Sea of Love came out. I stopped doing movies for four years. I just didn’t want to do this anymore. I did three things in a row that didn’t come off. One was, of all things, Scarface, which did good business, but had a real backlash — it was run through the mill. Then there was Author! Author! And then there was Revolution. Those three were not only not received well, they were really criticized in a way that made me think, “Well, what am I doing? I don’t want to keep doing this.” I did the films, yes. You do them sometimes because you try things. And my great friend and producer, Marty Bregman, who produced some of the biggest films I did, said to me a while back, “What’re you doing, Al? What’re you doing?!” I said, “What do you mean what am I doing? I want to explore certain things.”

He says, “You don’t explore with this! Go Off-Off-Broadway, explore! Don’t do it on the street!”

I said, “Well—”

“No! It’s not…no! Don’t do it there!”

Carlito's Way and Scarface are both part of the series "Pacino's Way," an Al Pacino retrospective that begins this week at the

Carlito's Way and Scarface are both part of the series "Pacino's Way," an Al Pacino retrospective that begins this week at the

John Lithgow spoke on stage the other day at Ringling College in Sarasota, Florida. The moderator was Bradley Battersby, the head of Ringling's film department who got his start as a student of Brian De Palma's when the director taught a class at Sarah Lawrence by making Home Movies with students there in 1979, with stars like Kirk Douglas, Vincent Gardenia, and several De Palma house regulars. Battersby went on to work with fellow students on films such as The First Time before directing the noir Blue Desert (1991, starring Courteney Cox), followed by several more pictures, including The Joyriders (1999), which starred Martin Landau and Kris Kristofferson (and also featured Elisabeth Moss).

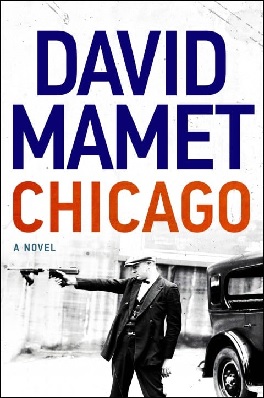

John Lithgow spoke on stage the other day at Ringling College in Sarasota, Florida. The moderator was Bradley Battersby, the head of Ringling's film department who got his start as a student of Brian De Palma's when the director taught a class at Sarah Lawrence by making Home Movies with students there in 1979, with stars like Kirk Douglas, Vincent Gardenia, and several De Palma house regulars. Battersby went on to work with fellow students on films such as The First Time before directing the noir Blue Desert (1991, starring Courteney Cox), followed by several more pictures, including The Joyriders (1999), which starred Martin Landau and Kris Kristofferson (and also featured Elisabeth Moss).  David Mamet's new novel, Chicago, takes place in the prohibition-era Chicago of the 1920s, and, according to

David Mamet's new novel, Chicago, takes place in the prohibition-era Chicago of the 1920s, and, according to