PART ONE

Matthew Chernov, Variety

The Best and Worst Stephen King Adaptations Ranked

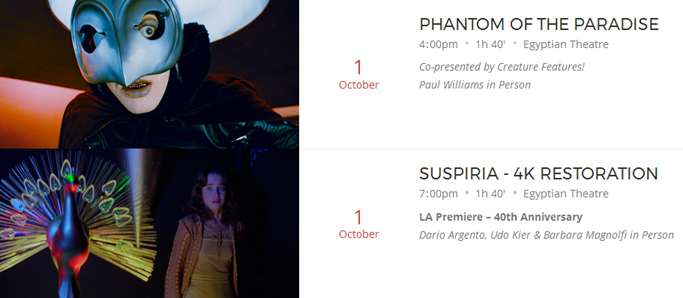

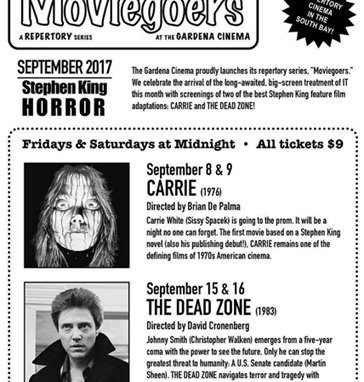

1. Carrie (1976)

Like a fairytale passed down for countless generations, King’s deceptively simple story about a lonely, mistreated teenage girl who unleashes her inner rage during the senior prom is so elemental and universal, it feels as though it’s been part of our collective consciousness forever. Miraculously, Brian De Palma’s dazzling film version only heightened the novel’s inherent strength. In the very first Stephen King adaptation, Oscar nominees Sissy Spacek and Piper Laurie capture every tragic nuance of Carrie and Margaret White, while up-and-comers like John Travolta, Amy Irving and Nancy Allen shine in colorful supporting roles. But it’s De Palma’s unsurpassed mastery of the medium that pushes “Carrie” to the top of the list. From the languidly erotic locker room title sequence to the electrifying final jolt, “Carrie” is in a class by itself.

Matt Zoller Seitz, RogerEbert.com

30 Minutes on: "It" (2017)

The sense of the creature's being intimately connected to the history of Derry doesn't come through as strongly as it might, though. That tends to sever the main characters from their town, minimizing the sense that an entire community has a stake in the outcome of the tale and turning it into more of a small-scaled, personal story about individuals conquering their demons by conquering an actual demon. The film treads lightly over his role in a racially motivated incident of arson in Derry's past—the burning of The Black Spot, a club frequented by black soldiers, by The Maine Legion of White Decency—and the gang of white bullies that regularly terrorizes our heroes never uses any slurs when harassing the lone black member of the Loser's Club (Mike Hanlon, played by Chosen Jacobs), leaving racial animosity more implied than stated. The movie also fails to connect particular horrific visions to the characters that inspired them in ways that would might them truly pop, as great setpieces in the Stephen King filmography do (the only girl in the group, Sophia Lillis' Bev Marsh, gets drowned in blood a la "The Shining" elevator not long after buying tampons in a drugstore, a vision worthy of Brian De Palma's original "Carrie," but there's little sense of the incidents being symbolically connected, a conspicuous failure for a horror movie of this type). At two hours and fifteen minutes, the movie also starts to develop a monotonous rhythm, serving up regular jolts at the ends of scenes where characters have a freaky/mysterious experience, almost always ending with Pennywise getting up in their faces or chasing them out of the room, his body shimmering and spazzing like a ghost in a Japanese horror movie.

Jordan Raup, The Film Stage

Review of It

With a more ceremonious unveiling than the other Hollywood adaptation of a Stephen King property this year, It is slickly calibrated to please its spook-hungry audience. Functioning more as a roller coaster ride of frights and humor than a dread-inducing exercise in terror, Andy Muschietti’s Mama follow-up doesn’t have the inspired vision or thematic complexity to join Brian De Palma and Stanley Kubrick in the pantheon of the (very few) masterful cinematic retellings of the celebrated author. However, for a Halloween precursor, there is a respectable amount of carnivalesque mischief to be found in this cinematic equivalent of a deranged jack-in-the-box.

Henry Bevan, The Flickering Myth

Remembering Carrie, the best Stephen King adaptation

The camera glides through the girls’ locker room. The girls are in various states of undress; steam from the shower creates a dreamlike quality, shrouding the scene, fogging up the lens. The camera pushes in on Carrie (Sissy Spacek) as she rubs herself with soap. It focuses on various parts of her naked body, before settling on a close up of her thighs. It lingers for longer than is comfortable as water trickles between her legs. Then, the water turns to blood.Pino Donaggio’s sensual score starts screeching as Brian De Palma perverts the male gaze, slashing the male fantasy of female representation by showing them something they will never fully understand: menstruation. The scene becomes horrific and is indicative of Carrie, Brian De Palma’s adaptation of Stephen King’s debut novel, a film whose horror lies in the director’s repeated attempts of rupturing film fantasy.

With It seemingly scaring up a massive opening weekend, it is an ideal time for articles on Stephen King adaptations (timeliness equals hits, normally) and Carrie remains one of the best adaptations because of how it grounds fantasy in reality. We are not scared of Carrie because of what she can do. We are scared of Carrie because we could be her. Everyone fears being picked on, being ridiculed, and everyone dreams they’d hit back at their bullies. Carrie, with her telekinetic powers, has the power to fight back, but she chooses not to. She massacres the student body only when the bullying gets too much.

At the Prom De Palma interrupts Carrie’s, and our, dreams. The soft lighting when she becomes Prom Queen turns sharp as she kills everyone in her path, even the “nice” gym teacher gets chopped in two. The murderous rampage shies away from gratuity, and, whether or not this is because of the limitations of the time, it helps makes the film feel real. The car crash looks like something you’d see on the news, it looks mundane.

While comparing films is a cheap form of criticism, Kimberly Peirce’s adequate 2013 re-imagining leans heavily into fantasy. Her car crash is a drawn out experience, captured in slow motion with more blood, and that’s saying something. It’s overt popcorn horror actually makes the film less scary, and even though 2013 Carrie’s powers are more empowering as she actively hones them and enjoys her revenge, it lacks the emotional resonance of someone exploding when they’ve been pushed too far. Peirce’s third-act horrors are how we think we would act in her situation. De Palma’s restrained third-act horrors are how we would act.

Carrie is as grounded in reality as a film featuring telekinesis can be. Carrie’s telekinetic bursts are surprising because they are not the story, they are the fantastical punctuation marks in her toxic reality. The story is concerned with bullying, sex education (lack of), and patriarchal domination; timeless themes and problems we still haven’t solved in the 41 years since the film entered cinemas. De Palma shows a filmmaking intelligence missing from most horror movies. He creates a terrifying film from skipping blood and jump scares, instead focusing on twisting fantasy moments and film language. The male gaze, a staple of most movies, is amped up to softcore porn levels before reality interrupts the fantasy with a trickle of blood.

Earlier this summer, HBO announced that Spielberg, a documentary on Steven Spielberg by Susan Lacy, will premiere on the channel October 7th. This week, it was announced that the film will have its world premiere at the New York Film Festival, which runs September 29 through October 15. The documentary includes new interviews with Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, John Williams, Tom Hanks, Robert Zemeckis, and several others.

Earlier this summer, HBO announced that Spielberg, a documentary on Steven Spielberg by Susan Lacy, will premiere on the channel October 7th. This week, it was announced that the film will have its world premiere at the New York Film Festival, which runs September 29 through October 15. The documentary includes new interviews with Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, John Williams, Tom Hanks, Robert Zemeckis, and several others.

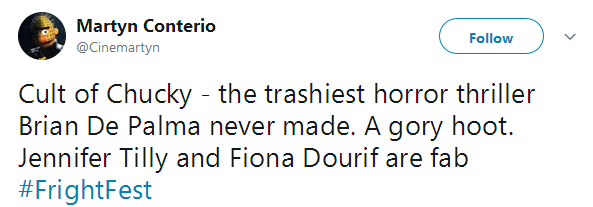

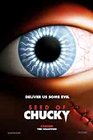

CHUCKY PAYS HOMAGE TO EARLY DE PALMA

CHUCKY PAYS HOMAGE TO EARLY DE PALMA Don Mancini, who has written all four of the previous films in the Child's Play series, is making his feature directorial debut with the upcoming fifth installment, Seed Of Chucky, which he also wrote. According to Fangoria magazine's January issue (the news of which you can read at

Don Mancini, who has written all four of the previous films in the Child's Play series, is making his feature directorial debut with the upcoming fifth installment, Seed Of Chucky, which he also wrote. According to Fangoria magazine's January issue (the news of which you can read at