SET IN 1985 MIAMI, RECALLING 'SCARFACE', BUT NOT REALLY

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | September 2013 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

ABS-CBN News' Vladimir Bunoan reports that Atlantis Productions' stage musical version of Carrie received a "prolonged standing ovation" following its opening night performance Friday in Manila. Mikkie Bradshaw, pictured here, plays the title role.

ABS-CBN News' Vladimir Bunoan reports that Atlantis Productions' stage musical version of Carrie received a "prolonged standing ovation" following its opening night performance Friday in Manila. Mikkie Bradshaw, pictured here, plays the title role.Bunoan quotes Bradshaw, who wrote on his Facebook page prior to Friday night's performance, "25 years ago, I fell in love with this musical. And here we are opening the first international production with an amazing group of people on stage and off. Feeling like that 18-year-old who saw the show in 1988. Blessed, grateful and inspired."

The new sitcom Dads premiered on the FOX TV network this past Tuesday, and the pilot episode included a quote from Brian De Palma's The Untouchables, which was written by David Mamet. It happens in an early scene in which the two main characters (played by Giovanni Ribisi and Seth Green), who own and operate their own video game company, are arguing about payback etiquette after one of them invited the other’s father to his surprise birthday party. Ribisi's Warner says to Green's Eli, "Hey, you send one of mine to the hospital, I send one of yours to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way." After a silent pause in which they stare at each other, they both smile and point at each other at the same time, saying, “The Untouchables,” and the tension is broken. The pilot episode is currently streaming on the FOX website.

The new sitcom Dads premiered on the FOX TV network this past Tuesday, and the pilot episode included a quote from Brian De Palma's The Untouchables, which was written by David Mamet. It happens in an early scene in which the two main characters (played by Giovanni Ribisi and Seth Green), who own and operate their own video game company, are arguing about payback etiquette after one of them invited the other’s father to his surprise birthday party. Ribisi's Warner says to Green's Eli, "Hey, you send one of mine to the hospital, I send one of yours to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way." After a silent pause in which they stare at each other, they both smile and point at each other at the same time, saying, “The Untouchables,” and the tension is broken. The pilot episode is currently streaming on the FOX website.

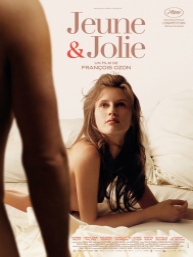

San Francisco Bay Guardian's Jesse Hawthorne Ficks writes about François Ozon's Young and Beautiful, which he saw at this year's Toronto International Film Festival (and which Brian De Palma saw at the Cannes Film Festival this past May). "Ozon has created a haunting thriller that should not be dismissed easily," states Ficks. "Young and Beautiful (France) follows a 17-year-old girl in what sounds an Eric Rohmer-esque portrait: four seasons, four songs. But while the rampant sexual excursions may get overlooked due to another French film this year... this tense tingler is much more diabolical than I was prepared for. It's darkly reminiscent of Brian De Palma and David Lynch — so, in other words, don't make any assumptions until the last frame is finished. Newcomer Marine Vacth delivers a fearless performance, but veteran Charlotte Rampling may have stolen the show with a role that calls to mind Under the Sand (2000) and Swimming Pool (2003)."

San Francisco Bay Guardian's Jesse Hawthorne Ficks writes about François Ozon's Young and Beautiful, which he saw at this year's Toronto International Film Festival (and which Brian De Palma saw at the Cannes Film Festival this past May). "Ozon has created a haunting thriller that should not be dismissed easily," states Ficks. "Young and Beautiful (France) follows a 17-year-old girl in what sounds an Eric Rohmer-esque portrait: four seasons, four songs. But while the rampant sexual excursions may get overlooked due to another French film this year... this tense tingler is much more diabolical than I was prepared for. It's darkly reminiscent of Brian De Palma and David Lynch — so, in other words, don't make any assumptions until the last frame is finished. Newcomer Marine Vacth delivers a fearless performance, but veteran Charlotte Rampling may have stolen the show with a role that calls to mind Under the Sand (2000) and Swimming Pool (2003)."

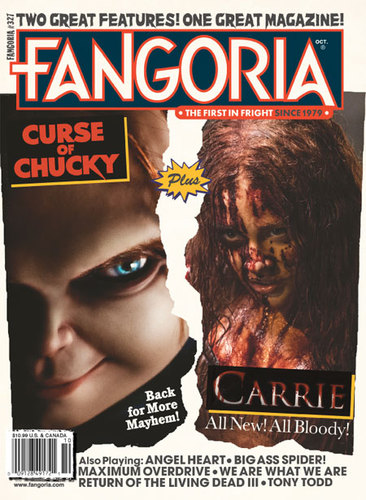

The Carrie featurette above includes interview clips with Chloë Grace Moretz, Julianne Moore, and Kimberly Peirce. The film opens in theaters a month from today, October 18th. The current issue of Fangoria features the film on its cover, and also includes an interview with Piper Laurie about her work on Brian De Palma's Carrie in 1976. The issue's "Monster Of The Month" is a drawing of Nancy Allen as Chris Hargensen from De Palma's film, and the "Crypt Lit" column looks back at Stephen King's original novel. The issue also includes an interview with Curse Of Chucky creator Don Mancini in which De Palma is mentioned a couple of times: interviewer Chris Alexander tells Mancini that he always viewed Seed Of Chucky as a "dirty De Palma film," to which Mancini points out that Pino Donaggio composed the score for it; there is also some discussion about how the lead actress in the new Chucky movie, Fiona Dourif, has an Amy Irving quality.

The Carrie featurette above includes interview clips with Chloë Grace Moretz, Julianne Moore, and Kimberly Peirce. The film opens in theaters a month from today, October 18th. The current issue of Fangoria features the film on its cover, and also includes an interview with Piper Laurie about her work on Brian De Palma's Carrie in 1976. The issue's "Monster Of The Month" is a drawing of Nancy Allen as Chris Hargensen from De Palma's film, and the "Crypt Lit" column looks back at Stephen King's original novel. The issue also includes an interview with Curse Of Chucky creator Don Mancini in which De Palma is mentioned a couple of times: interviewer Chris Alexander tells Mancini that he always viewed Seed Of Chucky as a "dirty De Palma film," to which Mancini points out that Pino Donaggio composed the score for it; there is also some discussion about how the lead actress in the new Chucky movie, Fiona Dourif, has an Amy Irving quality.Meanwhile, sometime tomorrow, Odd City Entertainment will begin selling a limited edition print of Jessica Deahl's original poster art for De Palma's Carrie. Each 16"X24" print will cost $40, limited to 150.

The Philippine Daily Inquirer reports that Atlantis Productions will stage the 2012 musical version of Carrie at the Carlos P. Romulo Auditorium from September 20 through October 6. Menchu Lauchengco-Yulo will play Margaret White, and Mikkie Bradshaw will play Carrie. Atlantis' artistic director, Bobby Garcia, will direct the show. He told the Inquirer, "It is a beautifully tragic retelling of the Cinderella story with an amazing Broadway pop score."

And EMPIRE Australia reports that the independent musical theatre Squabbalogic will also stage the 2012 musical beginning November 13, with 14 shows over three weeks at the Seymour Centre in Sydney. The article explains, "Artistic Director of Squabbalogic, Jay James-Moody, is without fear of the musical’s notorious 1988 Broadway failure (this production is based on the 2012 New York revival), as he’s daringly ready to present a Grand Guignol production that will paint the Sydney stage red. This musical version of classic cult, Carrie, will include a grand Australian cast, with Margi de Ferranti (Mamma Mia, Les Mis) playing Carrie’s ruthlessly cruel mother, Adèle Parkinson (Legally Blonde), Garry Scale (Hairspray), Monique Sallé (A Chorus Line), and debuting, emerging Australian actor, Hilary Cole, as the main character, outcast, Carrie White."

The new issue of the cinema journal L O L A went live yesterday, and it includes a dossier of four essays on the films of Brian De Palma, leading with a beautiful take on Passion (titled "To the Passion") by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin. Here's the inro to that article:

The new issue of the cinema journal L O L A went live yesterday, and it includes a dossier of four essays on the films of Brian De Palma, leading with a beautiful take on Passion (titled "To the Passion") by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin. Here's the inro to that article:As with all the best De Palma films, watching Passion (2012) should remind us of a contrary truth: when it comes to the exhilarating thrill, the wallop of cinema that his work gives us, it’s always the first time. Of course, there are broadly similar games with devious plots, POVs, split-screens, identity switches/disguises – play with the five senses and with every kind of media screen – in at least a dozen of his previous movies. But we were not thinking of Dressed to Kill (1980) or Raising Cain (1992) or Femme Fatale (2002) while we were absorbed in Passion: that type of unravelling always comes later. Nor were we trying to construct a hyper-intellectual contraption (in the manner of a recent woeful book) to ‘account for’ or explain away the intense, complicated, visceral pleasure we derive from his films.

When one of the main characters dies at the precise mid-way point, when the dreams and the dreams-within-dreams begin to unfold, when the camera tilts calamitously in a room or tracks in slowly to a face, when the plot lines pile up and converge on a single, catastrophic point … when these events, great and small, happen, we are not immediately flipping through the De Palma back catalogue; we are in the moment, the screen moment. Something that shakes us, that resonates, is happening there – we definitely know this by the final frames – and it is our task as critics to figure out what forces are involved, what has been deftly drawn into the fray. This task has nothing to do with taking the old Pauline Kael line that De Palma’s cinema is all about (and only about) energy, ‘pop vitalism’ and all-American vulgarity: such so-called ‘defence of trash’ too often clogs up the response-pores of even De Palma’s most public devotees.

Passion is not (as we are hearing a lot at the moment) a wilfully ‘ridiculous’ film (it is especially depressing to hear this said as praise!) or a self-consciously trashy one: these kinds of responses always tell more about the person uttering it than about the filmmaker in question. De Palma has gotten to a position in his career that is a little reminiscent of Samuel Fuller in his early-to-mid 1960s prime: his films mix vigorous, generic structures with sincere samplings of culture high and low (from viral YouTube videos to Jerome Robbins’ ballet choreography of Afternoon of a Faun); they meld expressionistic and melodramatic aesthetic patterns with a cold, hard edge of social criticism. And none of his films are so stringently, steely cold as Passion.

ALAIN BERGALA ON 'OBSESSION'

In "Time Denied: An Apotheosis of the Imaginary", Alain Bergala looks at the assumption of the image in De Palma's Obsession. "The major difference between Scottie in Vertigo and Michael in Obsession, states Bergala, "is that Michael is in a deeper sleep than Scottie. He wants to believe in the reality of his waking dream with a deep and naïve conviction. The whole film is an obstinate refusal to wake up, to leave the bliss of the imaginary. He rushes like a bull towards the first illusion that is offered to him – this woman who is the reincarnation of his dead wife."

In one section of the essay, Bergala discusses how De Palma's camera movements in Obsession follow the slowness of Stanley Kubrick's in Barry Lyndon: "A slow zoom-in draws the viewer into the bottomless pit of the imaginary. In Samuel Blumenfeld and Laurent Vachaud’s book of interviews, De Palma talks about the Kubrick of Barry Lyndon (1975), of the slowness of that film, of ‘the impression that everything was happening in slow motion: the movements of the camera and the actors. You really got the feeling of perceiving time in a different way, as if we had actually returned to the 18th century’. In the same interview, he claims, regarding the zooms that are used systematically in that film, that he would be bored, personally, to repeat the same technique throughout an entire film. And yet this is what he does tirelessly in Obsession, where he multiplies the long, fluid shots of the undulating imaginary."

"RESPONSIVE EYES AND CROSSING LINES"

In the fourth essay, "Responsive Eyes and Crossing Lines: Forty Years of Looking and Reading", Helen Grace presents an episodic look at her experience within the landscape of feminism over the years. In episode 3, she recalls the protests against De Palma's Dressed To Kill while in London in 1980:

"We saw Dressed to Kill, fearing that we would be shocked and horrified, and that we might come out convinced that screen terrorism was necessary. Instead, we watched a film which seemed to say more about masculine anxiety than about the fears that women were expressing in relation to the film. We kept waiting for the horror – and when it came, we enjoyed it. We wondered if we had seen the same film that people had been complaining about, so we went to one of the street meetings to discuss our problems. We found out that, in fact, none of the women had seen the film at all, and they did not want to hear our opinions about it.

"And this turned out to be a general feature in every situation in which a ‘citizen censorship’ movement called for the boycott of a film to which one group or another took offence, whether it was feminists and gays objecting to a Brian De Palma film, or Christians protesting the screening of Jean-Luc Godard’s Hail Mary (1985) five or six years later. It was exactly this period of the ‘80s when some strands of feminism seemed indistinguishable from right-wing Christian extremism in the anti-democratic gestures of, for example the Dworkin-MacKinnon Anti-Pornography Civil Rights Ordinance (1983) – which, fortunately, did not succeed. In any case, it was anti-pornography activism that first drew my attention to Dressed to Kill. And that is how I came to be a De Palma fan."

"[The Black] Dahlia was a portrait of Hollywood written in venom; Passion is a portrait of the corporate state drawn in arsenic. I do not think the title is an idle one – it is most definitely a play on the eternal passion, The Passion, as in The Passion of the Christ, a ridiculing of the modern ideal of corporation as creed, corporate life as the new religion, the corporation as a new christianity. The company which Christine and Isabelle work for is Koch Image International, and the coincidence of the name with a villainous fraternity is not, I think, idle either. The film is by an older man, yet it is a provocation on the order of Harmony Korine, undetected by viewers and critics: a corporate world re-telling of the Christ story. Christine’s name is a carryover from the original, but with a specific meaning: Christine."

The essay's author views Christine as an eternal martyr, citing the monologue in which she tells Isabelle about the twin sister who saved Christine's life. "When she gives this speech," reads the essay, "she of course wears a cross, but one appropriate to a corporate god: we’re unsure if it is has any significance other than jewelry, and most importantly, it has a very sharp end, so sharp you could stab someone with it."

In addition, "Christine has a disciple, but this disciple is a Judas, and gives her what is known as a Judas kiss." The author adds that Christine somehow "rises from the dead after a few days."

The author also delves into the costumes:

"Passion is a re-telling of the Christ story, but as a pagan tale. Christine starts out in the same mysterious gray as the title character of Femme Fatale before she takes on her new identity; then it becomes clear she is a sun god, and she is the only one to wear white outfits, then every color of the prism. She is a god of a materialist age as well, so she always wears jewelry, often ostentatious diamond pieces, and lives in a house with roman pornography and a Louis XV sofa.

"There is only one color she does not wear, and this appears in the shoes she wears in her resurrection. The death and return to life of the pagan god represented the cycle of the harvest, so of course the one missing color is the obvious one in a revived pagan god, a return to spring: green. She is a pagan god, but also a god of an uber consumer age, so the color of the resurrection shows up on pricey heels that Christine once loved."

The essay continues by looking closely at the costumes worn by Isabelle and Dani, with side-by-side comparisons with Love Crime appearing throughout. It also looks at the split-screen sequence, as well as the final dream sequence:

"The final sequence is a resolution of the idea of movies as revenge fantasy, images without consequence. Isabelle finds herself under someone’s will again, her escape from Christine only resulting in her confinement under Dani. The final dream sequence embodies all that is within her, a fear that she will be exposed for the murder, but also the simpler fear that she, this cryptic character, will be exposed, the way the sex tape exposed her. Isabelle does not want to be punished for the murder, and yet she wants to be punished. She wanted Christine dead, but she also wants her alive again. In this dream, both things happen, with Christine’s twin alive, and Christine’s twin magically appearing behind Isabelle in order to choke her to death. We in the audience wished Christine would die, without Isabelle being guilty, and in another movie we would have been granted this wish entirely: a villain like Christine would be killed, and after the hero was wrongly accused, the true killer would turn out to be someone else. We now wish Isabelle to escape her confinement from Dani, and yet we don’t want her to be a murderer. The audience is given its wish and it is taken away at the very same time, a reflection of this idea of images without consequences, dreams without any conenction to reality. We wish to dive into a mad fantasy of revenge, and then return to the sane world; we are here given our fantasy, but we are forbidden an escape. Isabelle chokes Dani to death, in a sequence nearly as graphic as Torn Curtain, with Isabelle’s face twisted into something of animal-like fury, yet it turns out to be but a dream, perhaps everything was a dream, but no: Dani is dead, strangled by Isabelle in her sleep."

Ben Sachs, Chicago Reader

Ben Sachs, Chicago Reader"Passion is a superficial film, but not an empty one. Amidst in the visual motifs, De Palma manages to touch on the following themes: corporate power, advertising, sexual desire, sadomasochistic relationships, and longing for love. The movie doesn't offer a coherent statement about any of these subjects, though De Palma interweaves them with a musicality comparable to his visual style. There's an odd poignancy to those moments where the themes related to dominance intersect with those related to vulnerability, suggesting that the pursuit of classical synthesis carries the risk of annihilation."

Will Noah, Double Exposure

"The film’s first half consists of deliberate set-up, or, to quote De Palma’s introduction to the film at last year’s NYFF, 'two black widow spiders circling each other.' At the midway point of the film, though, De Palma shifts into overdrive, bathing his images in blue light, slashing his compositions with diagonal lines, and piling twist after twist onto the increasingly frenzied narrative. The movie peaks in this half with a virtuoso split-screen sequence juxtaposing a ballet performance with a murder shot from the attacker’s perspective. This high-wire act justifies the movie’s existence on its own, hitting the dissertation-fodder-with-a-pulse sweet spot of De Palma’s best work.

"Passion has a hard time topping that brilliant set piece, though it sure tries, breaking into a last-act flop sweat that produces exhilaration and exhaustion in equal measure. That the movie ultimately collapses on itself is not much of a surprise; what’s more interesting is the paranoid atmosphere that the collapse generates. Above all, Passion is a movie fixated on the plastic qualities of images; as much as De Palma is interested in logos and fetishized bodies, he’s even more captivated by the digital forms that mediate them. In this film about deception, video is the ultimate shape-shifter, fulfilling many functions, often at once: advertising, surveillance, communication, pornography, evidence. The fact that De Palma shot Passion on celluloid seems not just a result of his automatic preference for the format, but a concerted attempt to assimilate all these forms of video under the old-fashioned heading of cinema. The fact that he doesn’t entirely succeed, ending up with a heap of jagged edges rather than a unified aesthetic whole, doesn’t constitute a failure so much as a psychological portrait of our image-saturated society. Passion is not merely an uneven erotic thriller; it’s a nightmare reflection of the confusion we face in a world where images manipulate us as much as we control them."

Robert Bell, Exclaim!

"Amusingly, Christine tells a story about a dead twin sister, which references De Palma's Sisters and later plays a trick on Isabelle that clearly reflects on the callous treatment of Carrie. An actual shot reconstruction from Raising [Cain] pops up in the final moments and the Body Double mask is omnipresent. This just scratches the surface of the inside joke observations peppered throughout this increasingly ridiculous melodrama, making the actual storyline between Isabelle, Christine and an even lower hanging fruit, Dani (Karoline Herfurth), secondary to the intense stylization and comedy of self-criticism that Passion really is.

"Still, McAdams clearly has a blast playing a calculating bitch and the inevitable hyper-stylized and meticulously edited climax sequence, which De Palma is known for, is as riveting in exaggerated comic form as it is in sincere thriller form.

"It's just unfortunate that those unfamiliar with the director's work will have absolutely no context for the abstract and oblique tonal shifts or the references, leaving them to dismiss the film as terrible."

Ian Bartholomew, Taipea Times

"McAdams and Rapace are beautiful pawns in De Palma’s own manipulative exercise in which he toys with the audience’s expectations, making uncertainty feel deliciously exciting. Complex, sometimes even a little confusing, De Palma always keeps things under control in this gorgeously orchestrated symphony of jealousy, betrayal and violence."

Tom Stoup, Sound On Sight

"The operatic Passion is pulpy perfection. By now Brian De Palma could probably sleepwalk his way through such material, but to his credit he appears to still be giving it his tireless all."

Bruce DeMara, The Toronto Star

"For a film with so much kink, seduction and sex, the film fails so badly in its execution —despite a quite promising first act — that one’s ultimate reaction is likely to be indifference, bemusement or outright disdain considering the pedigree of the filmmaker helming the project."

Chris Knight, Postmedia News

"The film, with its melodramatic score, numerous Dutch tilts, endless shots of people waking from nightmare imaginings and a bizarre split screen during a dance recital, looks like it’s trying to be the Black Swan of the advertising world. It’s a lofty ambition, but the problem with such a tightrope act is that one slip will kill the movie."

Harrison Foster, Just Press Play

"Passion, as a film, has a mind of its own as well, and a philosophical agenda that's even more consistent and explicit than that. Hiding in plain sight as what will seem a waste of time to most audiences, and a huge disappointment to most De Palma devotees, Passion slyly emerges as a manifesto of hostility toward new technologies, and movie culture's transition from cinema to streaming.

"It opens with an extreme close-up of that ubiquitous image that has found its way into not only what feels like every movie we watch, but every direction we look outside of the screen – that glowing white apple. Sure, that computer company's logo has been in films for years now, for much longer than people have lined up for its new products (in fact, its cinematic prevalence is one of the main reasons people starting lining up in the first place), but the product placement has never been this blatant, this transparent, or this loud. This goes beyond the allegedly satirical yet still effective ads peppered throughout Minority Report – a glowing apple that so obscenely dominates the frame inspires revulsion, not budgeting for a new small screen."

Liam Lacey, The Globe and Mail

"All of this is utterly non-naturalistic, with trite dialogue and broadly drawn performances. Shot in intense colours by Pedro Almodovar’s cinematographer José Luis Alcaine, it all resembles a melodrama performed on a fashion set. The schematic design is deliberately obtrusive: Isabelle has her own admiring hottie assistant, Dani (Karoline Herfurth), this time a redhead, to complement the blond Christine and brunette Isabelle. All this makes Passion, in a conventional sense, a bad movie: The performances are stiffly artificial, the characters’ machinations preposterous.

"It just happens to be a bad movie that’s good to look at. Then, at about the two-thirds mark, De Palma pushes the film to a new level of abstraction, in its pattern of doubling, coupling and severing images. It begins with a split screen: On the left is a modern-dance performance, set to Claude Debussy’s L’après-midi d’un faune – the recital will later serve as one of the characters’ alibi for a murder. On the right, we see the murder conducted with similar meticulous choreography.

The movie’s last third features more attention-grabbing camera moves, more bondage-gear footwear, more barred shadows, more plot complications and, for genre’s sake, a hang-dog middle-aged detective, Inspector Bach (Rainer Bock), who’s dumb enough to try to figure it out. By this point, the movie feels almost experimentally detached from its characters, a giddy assemblage of shots that summarize De Palma’s contribution to the thriller genre. There’s passion here all right, but it’s for the filmmaking, not the film."