SUMMARIES OF FIVE MORE ESSAYS

On Thursday, Feux Croises posted a De Palma Dossier made up of eight new essays about De Palma's cinema. That same day, I posted summaries of the first three essays. Here are summaries of the remaining five:

On Thursday, Feux Croises posted a De Palma Dossier made up of eight new essays about De Palma's cinema. That same day, I posted summaries of the first three essays. Here are summaries of the remaining five:In Le mauvais œil, Feux Croises' co-creator Cédric Bouchoucha looks at the way De Palma and his characters attempt to reconfigure space via editing, whether by placing a body double in a shower, or, as in Snake Eyes, showing two different points of view of the same event via split-screen. "For De Palma," states Bouchoucha, "this coexistence in the space of the frame, though impossible, can take several forms," including split-diopter shots that collapse the space between two characters, the aforementioned split-screens, and cross fades, such as the one in The Untouchables where the still image of the four crimefighters is replaced by the face of a smiling Al Capone. Discussing the "infinite sadness" of some of De Palma's characters as they fall into a world of disillusion, Bouchoucha notes of Passion that after Christine humiliates Isabelle in public, she asks here where her sense of humor is. "The terrible, unexpected laughter of Isabelle is a distant echo of Selina Kyle in the ballroom scene of Batman Returns."

In Woton’s Wake: Un conte d’un sculpteur et d’un cinéaste, Li-chen Kuo looks at how De Palma constructed a film about the cinema via the myth of a sculptor. Kuo notes the opening shot, which shows a bookshelf full of film books, with one title, "Woton's Wake," in flames and leaning against them, signalling a film about cinema. "The idea to animate the inanimable has been linked to cinema from the moment of its invention," Kuo states, "and the story of Pygmalion and Galatea had also been staged in 1898 by Georges Méliès. The film attempts to fix the figures by placing them in another medium and sets motion to the image. Cinema fixes them in their 'life', and thus declares the desire for movement. In sculptural art is also this transformation into 'real', into 'life.' These two arts, film and sculpture, attach themselves to common desires: the desire to see and touch." Kuo links De Palma to the sculptor played by William Finley, the latter creating a woman out of metal trinkets, the former "sculpting a film" out of several types of material, physical or conceptual. "How would you define the act of Brian De Palma in this film?" asks Kuo. "Close to his character, the filmmaker collects fragments of images, movie scenes, diegetic motifs, by cutting the film reel, sticking them back together, and ultimately shaping a new form." Kuo adds that this early short from De Palma "does not explicitly explore the question of point of view." As Luc Lagier has pointed out, Kuo writes, Woton's Wake was made in 1962, prior to JFK's assassination, and "could thus be considered a work still 'innocent'."

In D’envol en chute : ce qui hantera toujours De Palma, Sidy Sakho states that "All De Palma is indeed a history of vertigo, that of a man - often a woman - haunted by an image, a unique sound. The line of nearly all his stories is that of the absolute abandonment of heroes and an ideal that is forever elusive." Sakho further states that the resolution of the puzzle in a De Palma film is "above all a false movement, already dead" (or a stalemate). Sakho elaborates on this by describing the bombastic fanfare of the opening shot (sequence) of Snake Eyes as, cruelly, also being a swan song for Nick Santoro, as well as for the viewer. Sakho suggests that the gaze in De Palma's cinema is, like Ethan Hunt dangling just above the Langley floor in Mission: Impossible, forever caught "between the fall and impact, when fear of death and the hope of a recovery question one another."

In Cils conducteurs, Claire Allouche suggests that Chris Marclay's Up And Out, which presents the moving image of Antonioni's Blow-Up against the sound from De Palma's Blow Out, allows us to see the latter's images again, despite the sound being dissociated from its images. This puts the viewer of Up And out in a similar position to Blow Out's soundman protagonist, Jack. "In this sense," writes Allouche, "the plot of Blow Up could pass for a 'film location scouting' and that of Blow Out for 'film postproduction.'" Allouche further notes that Blow-Up is longer than Blow Out by five minutes, leaving the Marclay film to end in silence. "We do not know the meaning ascribed to Thomas," writes Allouche, "and yet our lost gaze is directed towards the imaginary game of tennis. Up and Out ends in a world where reality does not provide anything more to see and hear. The dark room is an anechoic chamber, a heart beating intensely as at the beginning of the De Palma film. Between terrifying scream and spellbinding silence, Up and Out takes one last breath. The 'blow' reasserts itself. But this time, it is ours."

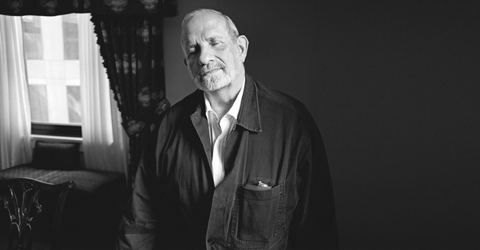

And finally, in William Finley, fantôme dionysiaque, Laurent Husson offers up a tribute to Finley as an important figure who "decisively contributed to forging the subversive tone of the De Palma cinema."

Updated: Sunday, March 10, 2013 10:59 PM CST

Post Comment | View Comments (1) | Permalink | Share This Post

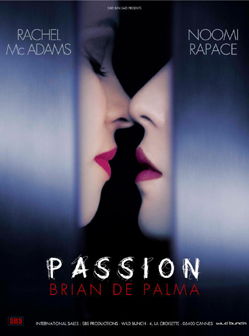

The soundtrack release for Brian De Palma's Passion hit mailboxes early this week, and, well, since I can't see De Palma's new movie yet, I've been listening to his new movie. (speaking of which, I received confirmation from someone in the U.S. today that Passion will indeed open in U.S. theaters sometime in June of this year.) Without having seen the film, I am guessing the track list has been put together in a non-chronological fashion (this has been confirmed in a comment below from someone who has seen the film), to present the music in the most compelling flow possible.

The soundtrack release for Brian De Palma's Passion hit mailboxes early this week, and, well, since I can't see De Palma's new movie yet, I've been listening to his new movie. (speaking of which, I received confirmation from someone in the U.S. today that Passion will indeed open in U.S. theaters sometime in June of this year.) Without having seen the film, I am guessing the track list has been put together in a non-chronological fashion (this has been confirmed in a comment below from someone who has seen the film), to present the music in the most compelling flow possible. Noomi Rapace spoke with

Noomi Rapace spoke with

Canadian entertainment magazine

Canadian entertainment magazine