REFLECTING THE '90s 'CRISIS IN MASCULINITY'

John Kenneth Muir continued his weekly look at the films of Brian De Palma last week with an essay about Raising Cain, which he calls "a satire, exposing the schizophrenic, contradictory messages sometimes sent by our culture to men of the day." Muir writes that the multiple personalities inside Carter (all played by John Lithgow) reflect the era's crisis in masculinity, leading to the inevitable transformation from a man into a woman:

John Kenneth Muir continued his weekly look at the films of Brian De Palma last week with an essay about Raising Cain, which he calls "a satire, exposing the schizophrenic, contradictory messages sometimes sent by our culture to men of the day." Muir writes that the multiple personalities inside Carter (all played by John Lithgow) reflect the era's crisis in masculinity, leading to the inevitable transformation from a man into a woman: Carter's many alternate personalities also expose further the crisis in masculinity. Cain is seen as inherently disreputable. He's a smoker for one thing (another big no-no in the Age of Political Correctness), and he's also, well, psychotic. Yet, Cain is the "man of action." Carter outsources his dirty work to Cain, because as a "sensitive" modern male he is deemed incapable of protecting himself or his family. When Carter gets into trouble attempting to subdue Karen, a local mother, Cain suggests that Carter kiss her to allay the suspicions of passers-by. This is something that would never occur to the diffident Carter on his own; but a solution which jumps out immediately to Cain. Cain is Id, through and through. The voice we all hear, but rarely act upon.

Yet another of Carter's personalities, Josh, has regressed to boyhood. He's a terrified child, one constantly fearing the wrath of his father. Again -- not entirely unlike Carter -- Josh is an image of masculinity reverted to a "harmless" or impotent stage, pre-adolescent, and therefore pre-sexual.

Finally, the guardian of the children is the personality named Margo. Importantly, Margo is female. Margo rescues Amy, destroys the Elder Dr. Nix, and restores order. It is a woman, therefore, who finally usurps the role of "hero"/"conqueror" in modern America. Carter can only become a hero when he is...female. The film's valedictory shot is of a looming, powerful Margo, standing heroically behind his family (Jenny and Amy). Carter could only be himself (a caring individual and care-giver) when in the personality and guise of a woman...and the last shot explains this visually. Margo is not menacing; not evil. She is triumphant.

Muir also describes the way De Palma uses space, movement, and the unbroken take to represent Carter's multiple personalities:When all this back-and-forth must at last be explained to the just-barely-keeping up audience, De Palma proceeds in snake-like, coiled fashion. He brilliantly stages an elaborate, lengthy tracking shot (approximately five minutes in duration) that follows two police detectives and Dr. Waldheim from the top floor of a police station down two stair-cases, through an elevator, down into the morgue,...where the shot ends on a close-up of a corpse's horrified expression of horror.

All throughout this masterful, unbroken shot, Waldheim explains the history of the Nix family and the theories underlying multiple personality disorders. She basically describes the events of the movie (Cain vs. Carter) in a fashion that makes sense out of perspective we've witnessed thus far. It's a journey from the top of Carter's mind, literally, to the bottom...to Cain's mind, where we spy his murderous handiwork (the corpse).

De Palma understands that form must echo content, and so the form of his film -- multiple perspectives coming together -- reflects the flotsam and jetsam Carter's splintered mind. The virtuoso unbroken shot is Waldheim's tour of that mind, a narrative maze of twists and turns, of science and ultimately death. But importantly, this tour is an unbroken one (like Waldheim's dissertation), making linear sense of the tale for the viewer.

Updated: Friday, August 14, 2009 1:13 AM CDT

Post Comment | Permalink | Share This Post

According to

According to

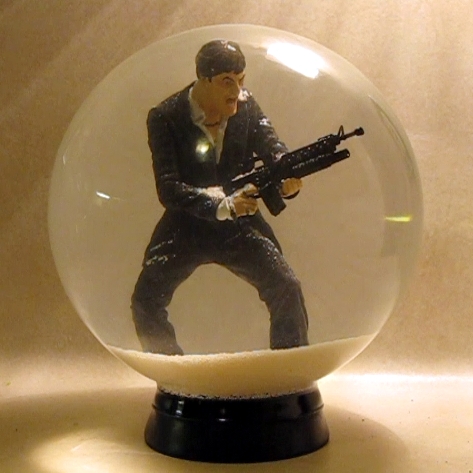

Gerard Butler, who had been set to play Jimmy Malone in Brian De Palma's planned prequel to The Untouchables, was asked about the status of Capone Rising in an interview in the August 2009 issue of

Gerard Butler, who had been set to play Jimmy Malone in Brian De Palma's planned prequel to The Untouchables, was asked about the status of Capone Rising in an interview in the August 2009 issue of