Updated: Tuesday, June 9, 2020 1:52 AM CDT

Post Comment | View Comments (2) | Permalink | Share This Post

Hello and welcome to the unofficial Brian De Palma website. Here is the latest news: |

|---|

E-mail

Geoffsongs@aol.com

-------------

Recent Headlines

a la Mod:

Listen to

Donaggio's full score

for Domino online

De Palma/Lehman

rapport at work

in Snakes

De Palma/Lehman

next novel is Terry

De Palma developing

Catch And Kill,

"a horror movie

based on real things

that have happened

in the news"

Supercut video

of De Palma's films

edited by Carl Rodrigue

Washington Post

review of Keesey book

-------------

Exclusive Passion

Interviews:

Brian De Palma

Karoline Herfurth

Leila Rozario

------------

------------

| « | June 2020 | » | ||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

De Palma interviewed

in Paris 2002

De Palma discusses

The Black Dahlia 2006

Enthusiasms...

Alfred Hitchcock

The Master Of Suspense

Sergio Leone

and the Infield

Fly Rule

The Filmmaker Who

Came In From The Cold

Jim Emerson on

Greetings & Hi, Mom!

Scarface: Make Way

For The Bad Guy

Deborah Shelton

Official Web Site

Welcome to the

Offices of Death Records

Here's a further excerpt from Taylor's article:

In June, 1975, Mission to Mars was first launched. It featured many of the same animatronics and even some of the same footage in the pre-show and ride film, but new elements were made to the show itself, both in terms of effects (inflatable seats would be inflated or deflated, to simulate space travel) and story points (hello, hyperspace travel). In 1975 Mission to Mars was installed in Disneyland too. But by the early 1990s, it was starting to show its age. It lacked the visceral thrills and excitement that modern audiences demanded and much of the science and technology was outdated and creaky. It closed in 1992 in Disneyland and 1993 in Walt Disney World. The mission had come to an end.Or had it?

Since the late 2000s, Disney had been noodling with the idea of turning some of its beloved theme park attractions into equally beloved big screen events. The test pilot was Tower of Terror, a 1997 horror comedy starring Steve Guttenberg and Kirsten Dunst that aired on Wonderful World of Disney and, more crucially, acted as an 89-minute commercial for The Twilight Zone: Tower of Terror, an innovative attraction that opened at what was then known as Disney-MGM Studios a few years earlier. (Part of the movie was actually filmed at the attraction in Florida. At the time MGM-Studios took pride in the fact that it was a fully operational production studio, even though hardly anything was ever shot there.) The movie was enough of a hit that several other projects inched through development, among them were big screen adaptations of Pirates of the Caribbean and The Haunted Mansion, along with Dinosaur, an animated film that was using state-of-the-art technology and was being developed alongside an attraction set to open at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Ah, synergy.

But the film that would ultimately make it out of the gate first was Mission to Mars. Part of this had to do with an arms race Disney was having with Warner Bros, who was developing their own Mars-themed project called Red Planet. (A couple of years earlier Disney had found itself in a similar situation as its own Armageddon squared off against Paramount and DreamWorks’ Deep Impact.) And part of it had to do with the fact that the studio really didn’t publicize that it was based on the theme park attraction, which at the time had been shuttered for the better part of a decade. The movies-based-on-theme-park-attractions idea appealed to Disney chief Michael Eisner but it still made him nervous. It was Eisner who made the last-minute decision to add the cumbersome subtitle to Pirates of the Caribbean in an effort to distance itself from the attraction. If Mission to Mars was a success, so be it. But the connections between the theme park attraction and the movie were not going to be explicitly drawn.

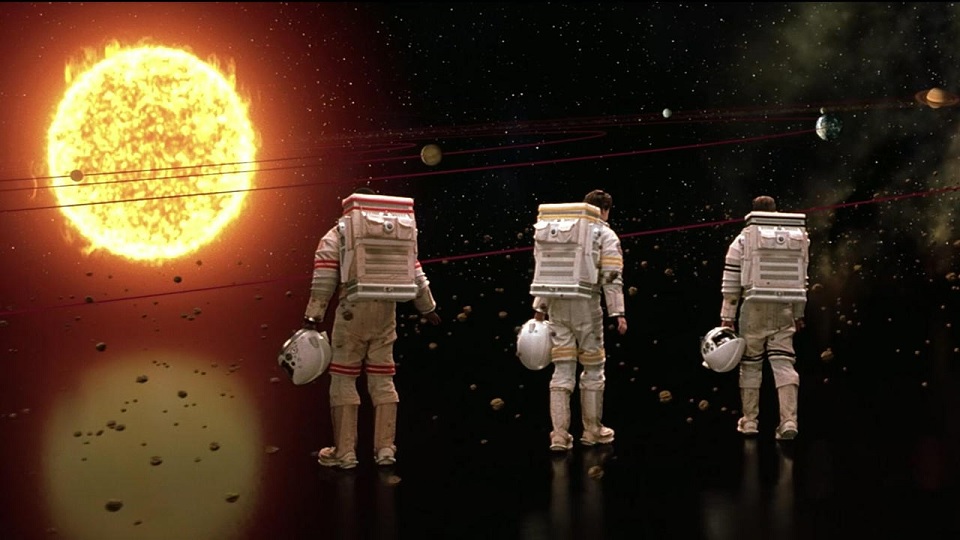

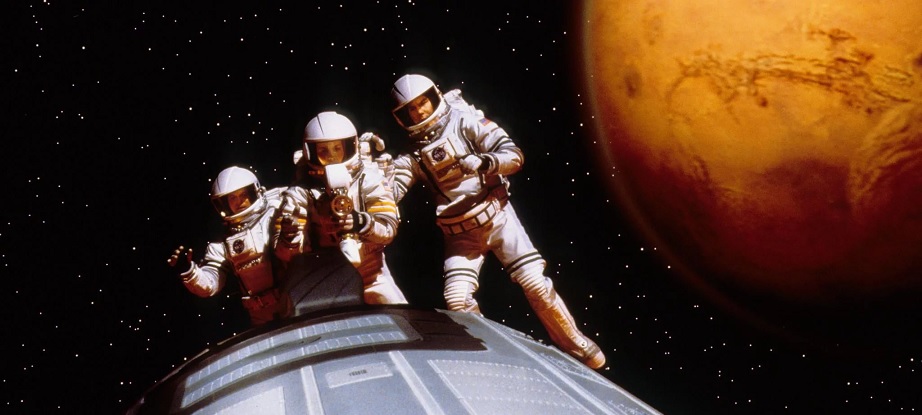

And, truth be told, the movie, directed by Brian De Palma from a screenplay officially credited to Jim and John Thomas and Graham Yost, doesn’t have a whole lot to do with the original attraction. Sure, it’s about an expedition to Mars. But there aren’t any direct parallels to be drawn, save from that amazing long shot, set to Van Halen’s “Dance the Night Away,” which features a rotating circular centrifuge, that explicitly recalls a similar image on one of the screens in the Mission to Mars preshow. (It’s a deep cut, I know.) Where there could have been references, there are emphatically not. You’d think that some of the characters could have had the last name “Morrow” or “Johnson,” references to the audio-animatronic figure that gave you the rundown in the ride’s pre-show. But, alas, there is none. De Palma, whose experience on the film wasn’t particularly positive (“It was relentless,” he said in the De Palma documentary), never mentioned the original attraction. It’s unclear if he even knew the film was an adaptation of a popular theme park attraction.

When Mission to Mars came out in the spring of 2000 (happy 20th!), it lost money, making $111 million internationally from a budget of over $100 million. De Palma was so broken by the project that he left the United States. “The Hollywood system we work in does nothing but destroy you,” De Palma said in the documentary. “When I finished that movie, that’s when I got on a plane and went to Paris. Mission to Mars was the last movie I made in the United States.” (Mission to Mars did get some strong notices from critics, particularly overseas. It was #4 on Cashiers du Cinema’s collective Top 10 that year, outranking The Virgin Suicides and In the Mood For Love.) But box office be damned, Mission to Mars was going to live on.

EPCOT had wanted a space pavilion since the early 1990s. It made sense. EPCOT (formerly EPCOT Center) was the science and discovery park. Space should have always been there. Initial plans called for a giant pavilion wherein several attractions would be accessible (one would have simulated a spacewalk, with guests suspended from an overhead track, peering into the outside of a space station) but budget cuts and the popularity of Horizons, a sort-of space-themed attraction about futuristic communities, occupying the same land that the new pavilion would have been placed, meant the space pavilion was off the table. But the idea was being revisited at the close of the decade; Horizons had lost its corporate sponsorship and a large sinkhole had been detected underneath its massive show building. They could finally do the really-for-real space pavilion and they had a cutting-edge idea to go along with it: spinning centrifuge that would make you feel weightless. They also had a flashy Disney movie they could piggyback on: Mission to Mars.

Disney enlisted Gary Sinise, one of the stars of Mission to Mars, to host the preshow for the new attraction, now called Mission: Space. (Sinise essentially is playing the same character but his name is never spoken.) And the big, wheel-shaped room from the “Dance the Night Away” scene is actually a part of the attraction’s extended queue, along with several model spaceships from the film (much of the visual effects work for the movie was provided by Dream Quest Images, Disney’s in-house visual effects company, that was shuttered following Mission to Mars’ release). On a narrative level, this new attraction borrowed heavily from the Mission to Mars attraction, including the conceit that you are being trained to make the journey to outer space and the patina of pseudo-scientific education. But this time the emphasis was on thrills.

So Mission to Mars, a movie inspired by a Disney theme park attraction, inspired another Disney theme park attraction. Moving in a circle, just like the astronauts in the movie. Who has the Van Halen?

Boredom Cultivator then responded, "Everyone says this movie is terrible but I watched it as a kid and there were multiple scenes that stuck deeply in my memory. I actually haven't re-watched it since but if it accomplished that I'm assuming it did something right." Lewis then added, "I liked it a lot!"

More responses followed:

Mark Asch: "a beautiful masterpiece, god-tier filmmaking, one of the greatest movies ever made"

DJSCheddar: "there are movies that I saw as a kid long before I ever knew anything about anything, but that despite not being big business or whatever, really stuck with me. this is one of them, to this day. really special"

quarantined fka ☕️ , fka ☕️: "I distinctly remember watching this with a friends family and all of them HATING it whereas I was p onboard"

the bane (the ape 🦧 parody): "dunno if the whole thing works but it goes hard"

Grafton Tanner: "Loved it when it came out. Haven't seen it since but looks like I need to"

Michael Snydel: "Remember being traumatized by this exact scene in the theater."

Will Mavity: "Man and he someone got that thing under the wire with a PG when you were having stuff stamped with a PG13 for 'thematic elements'"

Jake: "Best De Palma movie based on a theme park ride. At least until Disney drops their BLOW OUT attraction next to the Hall of Presidents."

Alex: "Haha oh man, I remember watching this as a little kid and the shot of Woody getting his face insta-frozen still sticks in my mind."

Jesse Hawken: "A handful of good scenes! Also: Guyliner Gary Sinese"

tsai ming-lad: "this goes so hard. great movie"

The Hipster Llama: "Ah I love this movie!"

Logan: "my favourite DePalma!"

Tyler Harford: "movie’s kinda underrated. has some of De Palma’s brilliant camerawork and i enjoyed its campiness and unintentional comedy."

OnryFans: "My high school had a series (8 - 12, can’t remember exactly) of bomb threats fall of my junior year. They’d check the auditorium first then stuff us all in there until it was over. We watched this once."

Chloe: excited to see how u feel about this one. moved me a lot."

Jesusfreak!: "Don Cheedle doing peek Cheedle before it was a thing."

billy: "Saw this in theaters at like age 8 and that scene ruined me"

The Scenic Route: "Still haven't forgiven this movie for mixing up chromosomes and base pairs."

Smarter than Every Economist: "Hahah this traumatized me as an 11yo"

Paresh Maharaj: "I remember seeing this movie in theaters but this is the only thing I remember (except maybe the ending)."

Collector of Unwatched Blurays: "Just watched this scene, and yeah, how did this get past not just the classification board, but also DISNEY?!"

C reel: "Man I saw this in the theaters when I was 10 this scene fucked me up"

"Lots of us have been bingeing pandemic movies, understandably," Sara Stewart states at the start of a New York Post article today. "It’s perversely comforting to see that things could be worse. But what else, I wondered, did film envision for us in 2020, specifically? I looked at five sci-fi movies set this year (and available for rent on Amazon, among other platforms) to see if things were better or worse than the real deal."

Stewart begins with Doug Liman's Edge Of Tomorrow, in which "tentacled aliens have taken over huge swaths of the globe and humanity seems to be permanently at war with them. (So: worse?)"

Then she moves on to Mission To Mars:

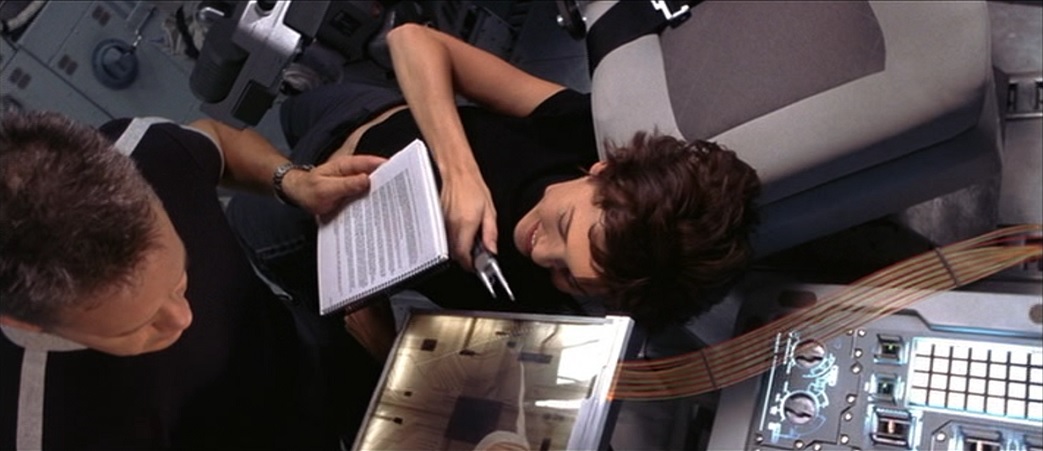

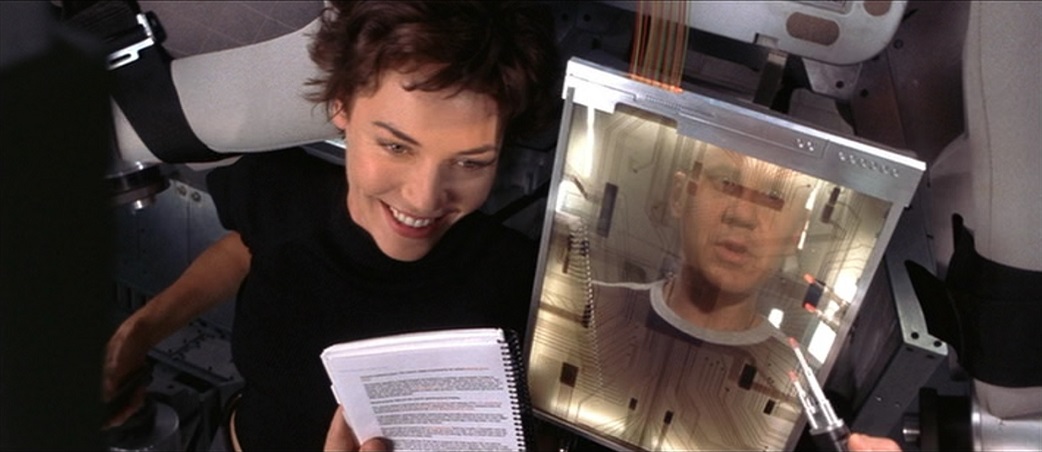

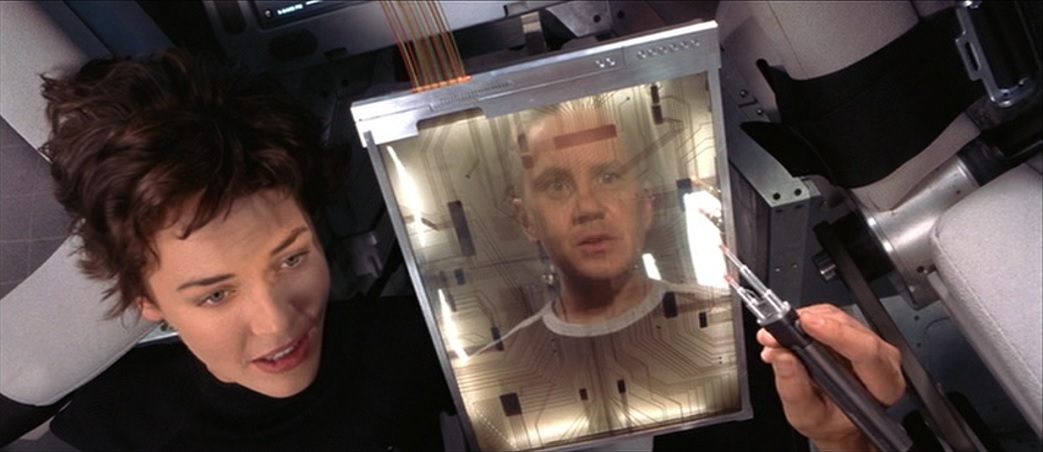

Next up: “Mission to Mars,” from 2000. Director Brian De Palma was clearly overly optimistic about our space exploration capabilities. Or was he? Three characters have died 20 minutes in, and there’s a giant face on the surface of the red planet. Yikes. Here’s a whisper of quarantine familiarity as a rescue mission finds that a scraggly Don Cheadle’s been tending a greenhouse alone on Mars for a year. Some of us may find a whisper of relatability here. This is a very cheesy movie, but it’s got a great scene of Tim Robbins and Connie Nielsen dancing in zero gravity. Also, we meet a Martian relative. On balance: better.

Christophe Hery: We ultimately delivered an illustrative look, but in making it we approached it from a more photoreal perspective, going as far as putting detailed displacement on the creatures and the terrain.The difficulties (and innovations) stem, besides the length, from the fact that we had to morph animals that were shaped quite differently, from early fishes to bisons, in the context of a herd (or school).

We approached these transformations by imposing a common topology on all creatures. This was an interesting exercise for the modelers and the riggers at the time, and they did a great job at that.

A tool was written on top of Cari [aka Caricature, a tool developed by ILM’s Cary Phillips], if I remember correctly, that would weigh the morphs in various regions of the bodies (so we could have, say, legs from crocodiles and necks from diplodocus appearing at different rates). All of this could be tailored and key-framed.

We had very fine control there, per limb, but we settled, again for illustration purposes, into a more unified morph speed. The camera is panning along from above, so it became hard to read the subtleties and we wanted the message to be obvious.

The morph weights were also automatically exported from this Cari extension into the shaders, so we would get a blend of the corresponding appearances automatically.

Surprisingly, the initial push into the water was the most difficult part to render. With all these bubbles motion blurred and very close-by, we were constantly faced with camera near clipping plane issues.

The shot was truly delivered/rendered as one continuous full CG shot (in Renderman). Only the actual footage of the astronauts and the alien hand were composited in (the alien being a separate CG render pass, obviously).

Meanwhile, at The Spool, Peter Sobczynski looks back at Mission To Mars, as well:

Although primarily known for dark suspense thrillers, Brian De Palma’s filmography is studded with a number of seemingly offbeat projects that one might not normally associate with the director of Carrie and Dressed to Kill. Even among his most ardent fans, though, a project like his 2000 effort, Mission to Mars, continues to serve as a bit of a bafflement. If you had to select the least suitable project imaginable for one of Hollywood’s most iconoclastic and cynical filmmakers, you could hardly do better than propose he make an expensive, optimistic PG sci-fi epic for Disney that was loosely inspired by one of their theme park attractions.The results were perhaps not very surprising. Aside from France, where it screened as part of that year’s Cannes Film Festival and was ranked #4 on Cahiers du cinema’s list of the best films of the year, it was a financial and critical failure. It’s rarely discussed today even amongst De Palma scholars. (De Palma himself only briefly touches on it in the documentary De Palma.) And yet, to watch it again 20 years after its initial release is an interesting experience.

It clearly pales in comparison to such works as Blow Out, Phantom of the Paradise, and Femme Fatale and it’s still wildly uneven in many ways. At the same time, to watch De Palma attempt to embrace new things in both genre and mindset is fascinating. It even contains one of the most absolutely spellbinding set pieces in a career that is not exactly wanting in that regard and as such, the end result makes sense in the grand scheme of his career.

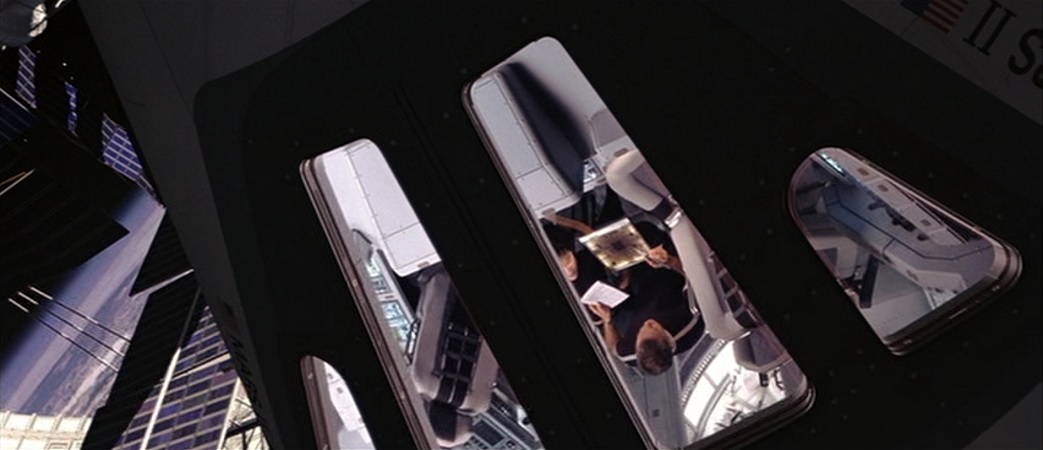

And yet, as clumsy as it can get at times, Mission to Mars does make for an intriguing addition to the De Palma canon. The film is not without its bleak and grisly moments—one scene features an exploding body that evokes the infamous finale of The Fury, albeit in a resoundingly PG-rated manner. That said, the storyline is ultimately hopeful and while it does lead to some odd moments (including what must be the least cynical deployment of the American flag in De Palma’s oeuvre), it’s surprisingly successful in evoking that kind of spirit without coming across as too forced.Better yet, the film is a visual marvel as De Palma, along with longtime collaborators such as cinematographer Stephen H. Burum and editor Paul Hirsch, creates any number of stunning images in which the constantly roving camera meshes with the feeling of weightlessness.

The highpoint of the film—indeed, the sequence that even its detractors admit is effective—is the stunning mid-film section in which a micrometeorite shower kicks off a series of ever-expanding disasters that culminates in the demise of one of the nominal stars at just barely past the halfway point. This sequence, which runs about 20 minutes or so, is De Palma at his best. It’s suspenseful, exciting, darkly funny, and constructed with jigsaw precision, and when it comes to its conclusion, it leaves viewers feeling a combination of shock and utter exhilaration at what they have just witnessed.

Seen today, Mission to Mars is just as much of an oddity as it was when it first came out and while it will almost certainly never be regarded as one of the great De Palma films by any stretch of the imagination, it does not deserve its reputation as a wholesale disaster that it gained virtually from the day it came out. (The film remains De Palma’s last Hollywood studio production as he would relocate to Europe after it came out to make films like Femme Fatale, The Black Dahlia, and Passion.)

At its lowest points, it is no worse than any number of anonymous space operas that have been produced over the years (including Red Planet, the competing Mars-themed thriller that it beat into theaters by a few months). At its highest peaks—specifically that still jaw-dropping mid-section—it serves a potent reminder of De Palma’s skills as a filmmaker. This is a film that is undeniably flawed but also undeniably ambitious and in a time when most films of this sort tend to forget to include the ambition alongside the elaborate visual effects, that does count for something in the end.

Inspired in part by a defunct ride at Disney’s theme parks, Brian De Palma imagined what humankind’s first manned journey to the red planet might play out. It is because the answer turns out to be “direly” that the film focuses the majority of its run time on the second such trip, a last-ditch rescue to extract the cosmonaut left behind by an accident the first time around. Let Elon Musk consider this a warning, as he and his top people at SpaceX vow to launch some undoubtedly rich eccentric into the deepest reaches of space by 2024: real people’s lives will be on the line, and even in the best-case scenario, we may still have to reckon with our genetic origins as bastardized Martian-DNA descendants. Which would, at the very least, level the market value of 23andMe.

The year 2000 was a wondrous time. The future had arrived! After surviving the Y2K threat anything seemed possible. Including traveling to Mars.That was the plot of the Brian De Palma-directed action film “Mission to Mars,” which depicted an ill-fated trip to the red planet in the year 2020. Hey, that’s now!

Set mostly in space, it didn’t offer much of a vision of what Earth would look like 20 years in the future, except for an opening scene at a July 4th barbecue for a team of astronauts potrayed by Gary Sinise, Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle and Connie Nielsen and Jerry O’Connell. All box office draws in the days before streaming.

Unfortunately, everything at the party looks very … normal. There’s no future tech to be seen and you probably could’ve recreated most of the wardrobe on a shopping trip to Old Navy and Ann Taylor. That said, no SciFi film worth it’s CGI would be complete without a car of the future, and MTM has one of those. Sort of.

Sinise’s character, mission co-commander Jim McConnell, arrives at the party in a bizarre-looking silver two-seat convertible SUV called the VX-02, with the 2 in subscript signifying the molecular formula for oxygen.

The thing is, it wasn’t really all that futuristic. It was a concept for a drop-top version of the Isuzu VehiCross that had gone on sale the prior year. The two-door 4x4 was a wildly styled take on the automaker’s mainstream Trooper and engineered with a conventional body on frame construction and V6 engine, the sound of which the effects folks replaced with electric motor noises on screen. (In the script posted on IMSDB, it’s described as a Jeep with a capital J. Ouch.)

Isuzu had introduced the VX-02 at the 2000 Los Angeles Auto Show a few weeks before the film’s premiere, pitching it as the world’s first Off-Roadster, but the market didn’t take a swing. Given the limited interest in the regular VehiCross – with just over 4,100 sold from 1999 to 2001 – it never made it into production and Isuzu left the U.S. altogether by 2009.

Nevertheless, the VehiCross has become a cult classic that has spawned the #VehiCrossTag on Twitter to accompany photos of sightings of the increasingly rare machine, and the VX-02 did predict the future in one small way.

At the 2010 Los Angeles Auto Show, Nissan unveiled the similarly oddball Murano CrossCabriolet convertible crossover, which went on sale the following year but was a commercial flop that was discontinued in 2014.

There was one more car at the party in “Mission to Mars” that is the antithesis of the VX-02. It’s a 1960 Chevrolet Corvette driven by Robbins' character Woody Blake that crewmate Luke Graham, played by Cheadle, suggests he should donate to a museum.

Blake’s response?

“Internal combustion, boys, accept no substitutes.”

Well, one person has: Elon Musk. And he's not only planning to go to Mars someday, but says he'll be bringing his electric Cybertruck along for the ride, which was inspired by 1982's "Blade Runner."

Who knows, maybe the VX-02 will finally go into production in 2038.

While most of cinema's predictions for 2020 rely on extremely advanced technology or outlandish creatures, one assumption about the future seems tantalizingly in reach with modern technology: a journey to Mars.Mission to Mars is an almost forgotten 2000 sci-fi film that's loosely based on the defunct Disney attraction of the same name. In the Brian de Palma feature, scientists travel to Mars, only for something to go wrong on their first manned mission, which requires a second team to investigate what happened. Along the way, the scientists make first contact with alien life and learn where the aliens went after Mars became inhospitable.

The film didn't impress audiences, nor did it make much money at the box office. Still, of all the films that take place in 2020, it's the closest to reality. The human race has the technology to reach Mars within the next few years, and we may very well actually make our way to the rusty fourth planet from the sun. We have far more of a chance making it there than blowing up continents, after all. Mission to Mars might've been nominated for Razzies in its day, but it wins in regards to scientific possibility.

Speaking of Domino, I happened upon a review of the Mission To Mars from 2006 (six years after the film's release), in which Slant's Eric Henderson argues for an auteurist approach to reading the film. Henderson's review of what he suggests is the start of "De Palma’s already richly rewarding 'old man cinema' period" seems to anticipate the back-and-forth views of Domino as "a De Palma film" these past few months:

Is Mission to Mars an auteurist litmus test for the Y2K generation in the same sense that Baby Face Nelson or The Girl Can’t Help It were in the theory’s salad days? Or is Mission To Mars the ultimate in hackery? Is De Palma etched into every CGI-loaded frame? Or can’t his personality overcome a budgetary tidal wave in the shape and magnitude of $80 million? While it’s tempting to shrug such questions off with a “go fiddle with your Hatari and jerk your Steel Helmet somewhere else, there’s formalism to be seduced here” (yes, even in this context of a critical appraisal of a singular talent), the impulse would rob an already gravelly underrated movie of its context. It would suck the air out of Mission to Mars like space robs Tim Robbins of his every last droplet of essential moisture. Leave a movie like Mission to Mars to fester among the slaves to the genre, and you’ll wind up with a bloated and laughably irrelevant Web page of technical gaffes over on IMDb. So while an auteurist reading of Mission to Mars might invite self-involved chatter over whether the movie or the viewer is supplying the meaning, at least you won’t find yourself sharing an oxygen mask with a caste of Trekkie outcasts. And Trekkies can’t dance in outer space.Buena Vista undoubtedly conceived of a very different film than the Mission to Mars it released in theaters. Its once and future pie-eyed protagonist is played by Gary Sinise, revealing executives’ intentions; this was meant to be a space movie aimed at those for whom Apollo 13, in which Sinise brooded and kicked clods of dirt while everyone else got to board the Good Ship Patriotism, was just a little bit too dark. Why they hired De Palma is beyond me, but they must’ve felt intensely pleased with themselves when the movie earned a kid-friendly PG rating. But Mission to Mars isn’t only a warm, up-with-people sci-fi actioneer in an Event Horizon era. It’s also a fearless twist on the sadly still controversial theory of evolution, a completely anti-James Cameronian epic with a blockbuster budget and a completely becalmed man at the helm, and maybe the first chapter in De Palma’s already richly rewarding “old man cinema” period. And did I mention that De Palma gets the chance to redux Fiona Lewis’s gothic pirouette of death from The Fury, only this time the limbs actually fly off?

Sure, De Palma may have been able to direct movies with an AARP card in his back pocket since 1992’s Raising Cain, but without Mission to Mars and Sinise’s haunted memories of Kim Delaney, De Palma could’ve never found it within himself to make Femme Fatale, his answer to that immortal one-two “old man cinema” punch of 1964: Hitchcock’s Marnie and Dreyer’s Gertrud. While the obvious connection between these three films won’t necessarily win over feminists for whom auteurism is another way of saying “no girls allowed,” all three mark a decisive point of psychological capitulation on the part of otherwise resolute personalities.

Mission to Mars’ redemptive coda opened the door for the subsequent film’s continuing figurative and literal sanguinity. There are few sights more disturbingly beautiful in the De Palma canon than Jerry O’Connell’s miniature globes of blood dancing in the air as they drift toward a hole in the Mars-bound shuttle’s structure. At once referencing bodily danger and assisting the crew and allowing them to repair a potentially greater danger, the fluidity of the film—from its blood to its serpentine cinematography—testifies to its elegance. Not to say there’s not a little hardening in De Palma’s heart even at this stage. It’s more a reflection of our culture’s reactionary values than of De Palma’s radicalism that this film airs on the Disney-owned ABC television network without its poetically direct 3D diorama of Earth’s evolution, suggesting the redolence of a corporation in hysterical self-censorship mode. But even De Palma turns the majority of the film’s saintly NASA heroes away at film’s end, leaving them to turn around and return to a planet of genetic inferiority. A planet where gravity makes it awfully difficult to dance through air.