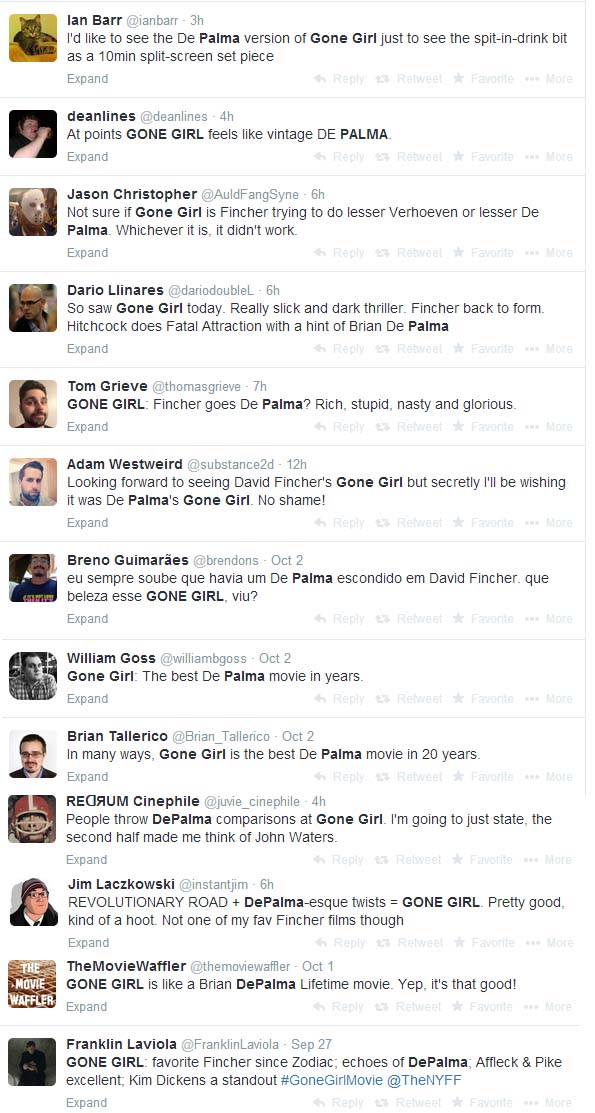

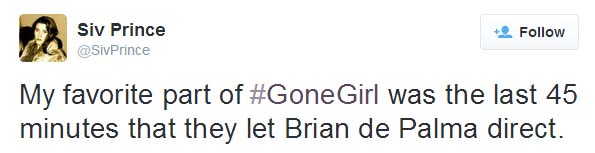

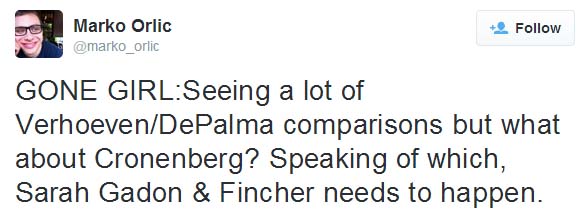

MORE EXCERPTS SURROUNDING 'GONE GIRL'

PIKE IS "A STAR IN THE BRIAN DE PALMA MODE," SAYS ONE CRITIC Richard Crouse, Canada AM

Richard Crouse, Canada AM"Affleck is a bright light but Pike burns a hole in the screen. The former Bond girl and

An Education star has never been better. Cold and calculating, terrified and terrifying, she puts the femme in fatale. A star in the

Brian De Palma mode, she’s capable of almost anything except being ignored. It’s a bravura performance and one that will garner attention come Oscar time."

Matt Zoller Seitz, RogerEbert.com"Like a lot of

Hitchcock—and like certain domestic nightmares by such filmmakers as

Brian De Palma and

Luis Bunuel—each scene in the movie refers, however obliquely, to real fears, real emotions and real configurations of love or friendship. But at the same time, not single frame is meant to be taken literally, as a documentary-like account of how people are, or should be, or shouldn't be. It's working through primordial feelings in the manner of a blues song, a pulp thriller, a film noir, or a horror picture...

"I'm not saying the film is genuinely clever throughout (though it is always fiendishly manipulative) or that every twist is defensible (a few are stupid). I'm saying that Gone Girl is what it is, that it knows what it is, and that it works. You know how well it's working when you hear how audiences laugh at it, and with it. Their laughter evolves as the film does. They laugh tentatively at first, then with an enthusiasm that gives way to a full-throated, 'I endorse this madness!' gusto during the final half-hour, when the story spirals into DePalma-style expressionism and the picture becomes a maelstrom of blood, tears and other bodily fluids. There are allusions to the O.J. Simpson case, Macbeth and Medea, and the ending is less an ending than a punchline that's all the more amusing for feeling so deflated."

Sasha Stone, Awards Daily

"A good comparison of Gone Girl is how Stephen King’s work has been adapted over the years. If you read The Shining you will discover an entirely different story in every possible way than what [Stanley] Kubrick put on screen, much to King’s own personal disappointment. But Kubrick made it cinema where it was horror fiction before (I think literature but hey, that’s me). Kubrick made it funny. It wasn’t funny. It was nowhere near funny. The Shining, as written by Stephen King is terrifying. Wendy is being hunted by her haunted husband and Danny has a power that makes the Overlook want to absorb him for it. Kubrick’s version did not delight critics in the least bit, and it certainly pissed off a lot of King fans. But Kubrick’s film is a cinematic masterpiece because it is about CINEMA. It’s about the color red. It’s about Jack Nicholson’s wildly off the wall performance. It’s that giant hotel swallowing up the skinny Wendy and tiny Danny. It’s about tracking shots and it’s about evoking terror. It’s about showing, not telling.

"When Brian De Palma made King’s wonderful first book, Carrie, it was a similar kind of transformation. It was kind of funny. It is different from the book in so many ways – for one thing, in the film Carrie is not repulsive. She is pretty, though freaky as Sissy Spacek realized her. This is what we talk about when we talk about the language of cinema – showing an audience a story that is meant to give you an experience over a two hour period sitting in a dark theater – it is not about the isolated wonder of making a book come alive in your imagination. Even films like the Shawshank Redemption or Stand by Me or Misery or Dolores Claiborne completely alter what was written on the page. They have to. They’re movies, not books. Vive la difference.

"It is therefore very telling how different people interpret Amy in Fincher’s film. Here is a director like Kubrick or De Palma who has taken a familiar book with familiar characters and found a new way to tell that story using the language of cinema, not the language of fiction. He found in Gillian Flynn a writer who understands both. So that this attempt to find the goodness in Amy, or to want to see one’s own definition of a “cool girl” is to want the movie you made in you head rather than the one these artist’s rendered. People seem so urgent about making Amy somehow good. Perhaps, while reading the book, they were able to remake Amy as a more palatable person. But Amy, fully fleshed out on screen, is the collaboration of an actress, a director and a writer who found this cinematic Amy, quite different from the Amy as written on the page."

Lou Lumenick, New York Post

"Enter a celebrity lawyer named Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry), as well as tabloid journalists loosely modeled on Nancy Grace (Missi Pyle) and Barbara Walters (Sela Ward). Not exactly biting satire or social commentary. Fincher is on more solid ground with trashy thrills — including an artfully staged (and gory) murder reminiscent of Brian De Palma."

Andrew Parker, Dork Shelf

"Following a recent string of prestigious films that established filmmaker David Fincher as someone who always gets talked about during awards season whenever he makes a film (and a side trip to direct the English language remake of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo), he has seemingly returned to his gleefully nasty, more culturally misanthropic roots with Gone Girl. It’s an absolute blast to watch blending sly wit, campy theatricality, perfect casting, and Fincher’s uniquely controlled style of direction. People who yearned for the day where Fincher would make another film like Fight Club or The Game have gotten their wish. Gone Girl is the best Brian De Palma film that Brian De Palma never made."

Josh Bell, Las Vegas Weekly

"It may not be fair to judge a movie by who didn’t direct it, but watching David Fincher’s meticulous, sterile adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s nasty pulp novel Gone Girl made me wish that someone with a little less restraint were behind the camera.

"We’ll never find out what Brian De Palma’s or Oliver Stone’s or Eli Roth’s Gone Girl would have looked like, and it’s not as if Fincher does a bad job with the material, aided by a screenplay from Flynn herself. Indeed, Fincher’s Gone Girl is often riveting, and the movie streamlines some of the novel’s most excessive elements, with brisker pacing (even at nearly two and a half hours) and greater narrative momentum. It’s a solid, sometimes seriously unsettling movie, with a number of very good performances, but it’s still second-tier Fincher, a faithful literary adaptation along the lines of his last film, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, without the larger resonance of movies like Zodiac and The Social Network."

Richard Brody, The New Yorker

"Gone Girl is David Fincher’s Eyes Wide Shut. As Stanley Kubrick did in his final film, Fincher lifts the lid off the black box of marriage. He reveals the core of unredressed resentment, unfulfilled desire, inescapable duplicity, unrelieved anger, unresolved doubts, unrevealed secrets, and relentless self-abnegation on which the life of a couple depends. But Gone Girl goes a step beyond Kubrick’s film, by rooting the action in the particulars of the digital age. The new public realm—the intentional representation of private life in public view and the way that those representations quickly get out of hand—is at the center of Fincher’s movie. And it’s from here that the movie’s modernity, immediacy, and urgency arise.

"Fincher is the exemplary digital artist of the contemporary cinema. For him, the world of modern media is far more than a source of information. It’s a new realm of mind, and it comes with its own myths and symbols, angels and demons. The power of Gone Girl isn’t in its plot alone. Though I started out warning about spoilers, there isn’t much temptation to analyze the movie’s plot in detail. This is no mere avoidance of spoilers; it’s a reflection of the movie itself, in which the plot quickly melts into the ideas that sustain it.

"In its simplest form, Gone Girl is a story of revenge. The marriage of Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck) and Amy Elliott Dunne (Rosamund Pike) is a troubled one. The sources of conflict are simple and clear: money difficulties; a sexual cooling-off; unease with the in-laws; Amy’s sacrifice of city life for Nick’s home town in Missouri, where they move so that Nick can care for his ailing mother. But there’s worse: Nick is an adulterer, and has been violent to Amy, not with weapons or fists, but crossing the line nonetheless, breaching her trust and instilling fear with the implicit threat of worse to come. The law doesn’t get involved with adultery, and in this case it doesn’t get involved with assault, either. What’s left is personal vengeance and divine or karmic retribution.

"Nick is no angel, but the revenge that follows seems somewhat disproportionate to his offenses. Fresh from a screening, I mentioned on Twitter that I saw equal measures of misogyny and misandry in the film, and that they join in a 'tender misanthropy.' It takes a jaundiced view of the human condition to judge the institution of marriage on the behavior of its inmates. If Fincher’s view of marriage seems similar to that of Eyes Wide Shut, his view of Nick seems derived from Alfred Hitchcock’s vision of the amiable family man as played by Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man: he’s certainly guilty of something, and it will come out if his life is scrutinized—which it is, when Amy disappears and he’s accused of her murder.

"But the hidden crime would also come out if Nick looked deeply or closely enough at himself—if he subjected himself to the infamous Jimmy Carter standard of candor. (It’s oddly apt that Gone Girl is opening on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.) Ultimately, the evils that are being redressed in Gone Girl aren’t one husband’s indifference or cruelty but all men’s crimes through the ages. What could easily have devolved into a bunny-boiling melodrama turns into the ultimate #YesAllMen drama becomes a version of Medea and The Bacchae dressed in the shopping-mall garb of uneasy and struggling suburbanites. In the course of Nick’s travails—his subjection to televised character assassination, police interrogation, and street harassment—he speaks the movie’s key line, with its Euripidean wink: 'I’m so sick of being picked apart by women.'

"Fincher’s not offering an essentialist view of gender but rather slicing and stretching Nick and Amy at their particular points of sensitivity. What’s gendered isn’t the world at large but the life that Nick and Amy have chosen. And it’s that life, not the biology of gender but their chosen social roles, that erupts with a violent mythological force through the neutrality of the media. With a digital prestidigitator’s swiftness, Fincher keeps the action moving forward even as the real action is happening offscreen—in the past or in the future, in memory or fantasy or fear, somewhere else or even, for that matter, nowhere. (That’s the moral essence of the digital age: people staring at their screens, for whom whatever is in their presence is less important than what is happening somewhere else.) Gone Girl is as much of a revelation and an artifact of digital life as Zodiac, Benjamin Button, and The Social Network.”

Chris Fyvie, The Skinny

"The brilliance of Gone Girl cannot be overstated, nor can it really be elucidated without diluting its many, many pleasures. This is a contradiction, a quandary, of which David Fincher and screenwriter Gillian Flynn (adapting her own bestseller) would no doubt approve. Unspooling from the suspicious disappearance of outwardly icy and unlovable Amy Dunne (Pike), both in flashback, to the beginning of Amy and husband Nick’s (Affleck) relationship, and in the present, as Nick somewhat half-heartedly attempts to recover her, there is something not quite right about everything on screen; a strangeness maintained in no small part by the leads’ mesmerising, layered performances.

A tricksy mystery, an ironic, bat-shit crazy erotic thriller of the type Joe Eszterhas and Brian De Palma in their pomp might think too lurid, and a sharp satire of pervasive tabloid media and the parasitic communal grief it fosters in times of personal crisis, the picture hinges on and delights in its ambiguity. And its artifice; while Fincher and cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth’s frosty, voyeuristic gaze is deliberately incongruous, the excellent, subtle supporting turns from talented TV actors (Dickens, Coon, Harris) and a shameless tack-merchant (Perry) both subvert and compliment the tawdry subject matter. It’s gloriously deep, with a despair at humanity typical of the director's work, but Gone Girl also succeeds purely on its gorgeous, thoroughly entertaining surface. One of Fincher's finest, and certainly his most playful."

7 Films To Watch Before Seeing Gone Girl

Nick N., The Film Stage

(the 7 films chosen by the staff: Basic Instinct, Body Double, Dressed To Kill, Eyes Wide Shut, Psycho, Vertigo, The Vanishing)

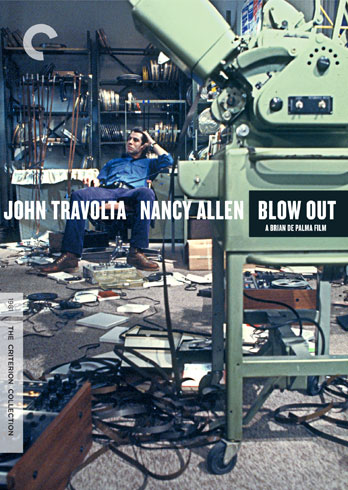

"Although I come to you as a man who’s not yet seen Gone Girl, I do consider myself something of a Brian De Palma expert, and knowing what I know about David Fincher’s latest film allows me to say you’ll probably get a bit more out of it if Dressed to Kill and Body Double are experienced beforehand. That this is tiptoeing around spoilers would both acknowledge the need to preserve some surprise and also tip the cap to De Palma, whose immense formal talent can make the bombastic and stupid utterly sublime — a trait one might apply to Fincher himself. Even if you have no desire to check out his 2014 offering, at least allow another director to give you some slick sleaze."

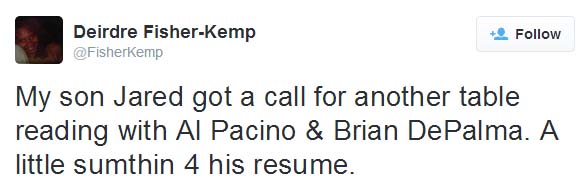

Following up on his role as Twisty The Clown on this past week's season premiere of American Horror Story, The Star Tribune's Neal Justin profiled actor John Carroll Lynch the other day. Late in the article, Justin brings up HBO's currently-suspended production of Happy Valley, for which Lynch has been cast as Jerry Sandusky. Al Pacino will play Joe Paterno, and Brian De Palma will direct from a script by David McKenna. "Your guess is as good as mine,” Lynch tells Justin when asked if he thinks the movie will ever be made. “I believe it’s still alive. I think it’ll get done. It’s the perfect part for Al, and the script is excellent."

Following up on his role as Twisty The Clown on this past week's season premiere of American Horror Story, The Star Tribune's Neal Justin profiled actor John Carroll Lynch the other day. Late in the article, Justin brings up HBO's currently-suspended production of Happy Valley, for which Lynch has been cast as Jerry Sandusky. Al Pacino will play Joe Paterno, and Brian De Palma will direct from a script by David McKenna. "Your guess is as good as mine,” Lynch tells Justin when asked if he thinks the movie will ever be made. “I believe it’s still alive. I think it’ll get done. It’s the perfect part for Al, and the script is excellent."

It's getting difficult to keep up with all the screenings of Phantom Of The Paradise happening around the globe as it celebrates its 40th anniversary. Last night, Brian De Palma's classic screened at the Buffalo International Film Festival, according to

It's getting difficult to keep up with all the screenings of Phantom Of The Paradise happening around the globe as it celebrates its 40th anniversary. Last night, Brian De Palma's classic screened at the Buffalo International Film Festival, according to

Earlier today,

Earlier today,

Musician Austin Garrick, who wrote and coproduced the theme song for Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive,

Musician Austin Garrick, who wrote and coproduced the theme song for Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive,