"IS IT OKAY TO WATCH THIS?"

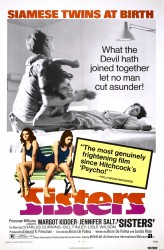

Brian De Palma's Sisters screened in Chicago last night as part of Doc Films' De Palma Retrospective, running Wednesdays through March at the University of Chicago. Cine-File included the screenings (it was shown twice) in the "Crucial Viewing" portion of its weekly guide to alternative cinema. Contributor Kian Bergstrom wrote very enthusiastically about the film:

Brian De Palma's Sisters screened in Chicago last night as part of Doc Films' De Palma Retrospective, running Wednesdays through March at the University of Chicago. Cine-File included the screenings (it was shown twice) in the "Crucial Viewing" portion of its weekly guide to alternative cinema. Contributor Kian Bergstrom wrote very enthusiastically about the film:"After a decade in training," Bergstrom begins, "making movies that are variously interesting (GREETINGS, THE RESPONSIVE EYE), fascinating (HI, MOM!, MURDER A LA MOD), or catastrophic (GET TO KNOW YOUR RABBIT), De Palma burst into artistic maturity with this astonishingly accomplished and subtle masterpiece. It marks the moment De Palma went from being the geekiest of the American New Wave brats to simply the greatest American filmmaker working, a title he's maintained with an almost unbroken string of subsequent wonders. Like many of De Palma's films, SISTERS is antagonistic towards its audience, barraging us with images of brutality, damaged bodies, damaged people, pushing us uncomfortably interrogating us at all times to defend our continual decision to keep watching. It is as though every segment were structured around a question, asked of the audience, as to whether the upcoming visual offense would finally prove to be too much for us to justify. Is it OK to watch this? would be film's ideal motto, with the emphasis on the question mark. At its heart are the Blanchion twins (in a disarming and mesmerizing performance by Margot Kidder), conjoined at birth but surgically cloven from one another as young women. A young model in New York, Danielle picks up a fellow game show contestant, only to find her erotic trajectory frustrated by her astonishingly creepy ex-husband, Emil. Eluding Emil, the amorous couple finds their way into bed together with the casual revelation that the next day will be Danielle's birthday. But that birthday brings with it not joy but murder as Dominique, the evil twin of sweet-natured Danielle takes control of the narrative. As always with De Palma, though, there's much more at play than there seems. Quick as a knife-strike, he introduces the real main character, Jennifer Salt's Grace Collier, a combative investigative journalist whose apartment overlooks the twins' abode. Desperate to discover who her strange neighbors really are, and what they really did with the body she saw killed there, Grace and a private detective pry into the history of the Blanchions, only to discover that peering to closely into their lives threatens indeed their own very existences. SISTERS moves rapidly through a succession of set-pieces, each extraordinary in stylization, exacting in execution, and monstrous in implication: invasions of privacy, hypnotism, madness, and horrifying errors of judgment. This is a film troubled by doubles, by two detectives, by two policemen, by twins, and also by duplication: the duplication of a person when death strikes, the duplication of an image by the television screen, the duplication of cells within a woman's womb, the duplication of space by the split screen. Many critics of De Palma see him as working in hermetic structures, narratives so precise and specifically and idiosyncratically realized that his films are comprehensible only when we understand them to be entries in grand artistic conversations with his inspirations (Hitchcock, Hawks, Lang, Welles). They miss so much: the nausea the film expresses towards the casual misogyny and power of the mysterious Emil; the fragility of the social world, as easily ripped to shreds as a Grace's thin shirt; the arbitrariness of the normal, broken and shattered by the slightest action. SISTERS is no insular work, pillaging all its best ideas from Hollywood's graying masters, but a living, beating, furious wasp's nest of a work, stable at a distance, but ready to explode with the slightest touch."

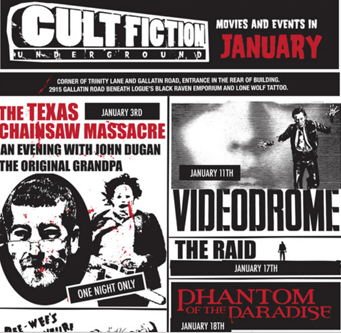

Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise, which turns 40 this year, is part of the January line-up at Nashville's

Brian De Palma's Phantom Of The Paradise, which turns 40 this year, is part of the January line-up at Nashville's