LANDMARK SILENT FILM, WITH ITS INNOVATIVE TECHNIQUES & CELEBRATED ODESSA STEPS SEQUENCE

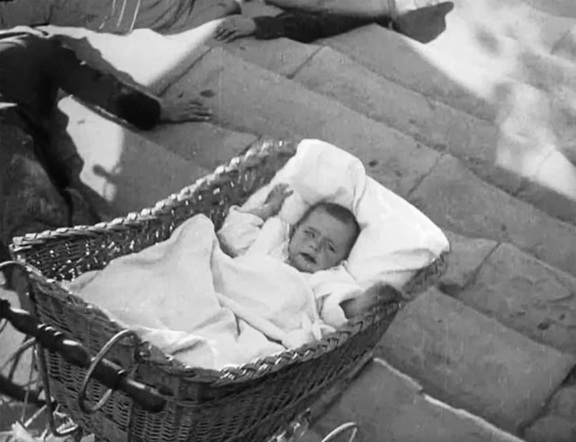

At The Wall Street Journal, film historian Peter Cowie writes about Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin as "an unshakable monument in the history of world cinema" that "opened 100 years ago this December, at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. Ever since its re-release in the early 1950s," Cowie continues, "Battleship Potemkin has been consistently rated among the greatest films ever made, and has influenced numerous creative artists, from the notorious Leni Riefenstahl in her propagandist documentaries to the painter Francis Bacon, who was inspired by the agonizing images of the Odessa Steps sequence, as was Brian De Palma in making the railroad-station scene in The Untouchables."

Here's a brief excerpt from Cowie's article:

Eisenstein saw the film as an opportunity to test his theories of montage, which were innovative at the time. He believed that it was much more than just the editing of shots, and that the tone and rhythm of montage could be used to influence the intellectual and emotional response to art. He worked closely with Tissé to ensure that huge close-ups of human faces distorted with anguish or fury would exert the maximum effect on audiences of the time. The long shots in “Battleship Potemkin” are equally eloquent—ships at anchor in the dusk, a line of mourners stretching as far as the eye can see along a harbor wall. Eisenstein asserted that the film “looks like a newsreel of an event, but it functions as a drama.”“Battleship Potemkin” attracted international acclaim only after Eisenstein had traveled to Berlin and arranged for the Austrian composer Edmund Meisel to improve the score for the film, creating distinctive music for each scene and working with Eisenstein to give a vibrant cadence to the more dramatic sequences. “I need rhythm,” Eisenstein told his composer, “rhythm, rhythm!” Meisel obliged with a score at times touching 120 beats per minute.

The “inter-titles,” usually ponderous in silent cinema, are fluent and compelling, ensuring a relentless drive that propels the story forward. The plastic symmetry of “Battleship Potemkin,” its humanity, and its throbbing power still command respect, and Sergei Eisenstein endures as the finest film editor the world has seen.