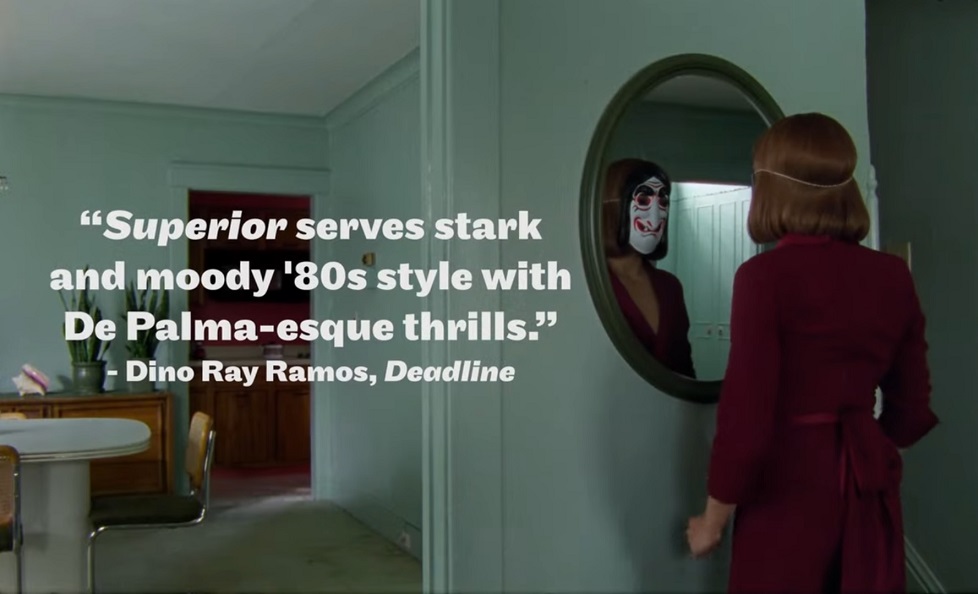

A 'LOVE LETTER TO BOTH HITCHCOCK & BRIAN DE PALMA'

REVIEWS ARE POPPING UP FOR SODERBERGH & KOEPP'S NEW HBO FILM, 'KIMI', STARRING ZOE KRAVITZ

Premiering on HBO Max tomorrow,

Steven Soderbergh's new film,

Kimi, was written by

David Koepp, and stars

Zoë Kravitz. Reviews for the film have been popping up today:

David Rooney, The Hollywood Reporter

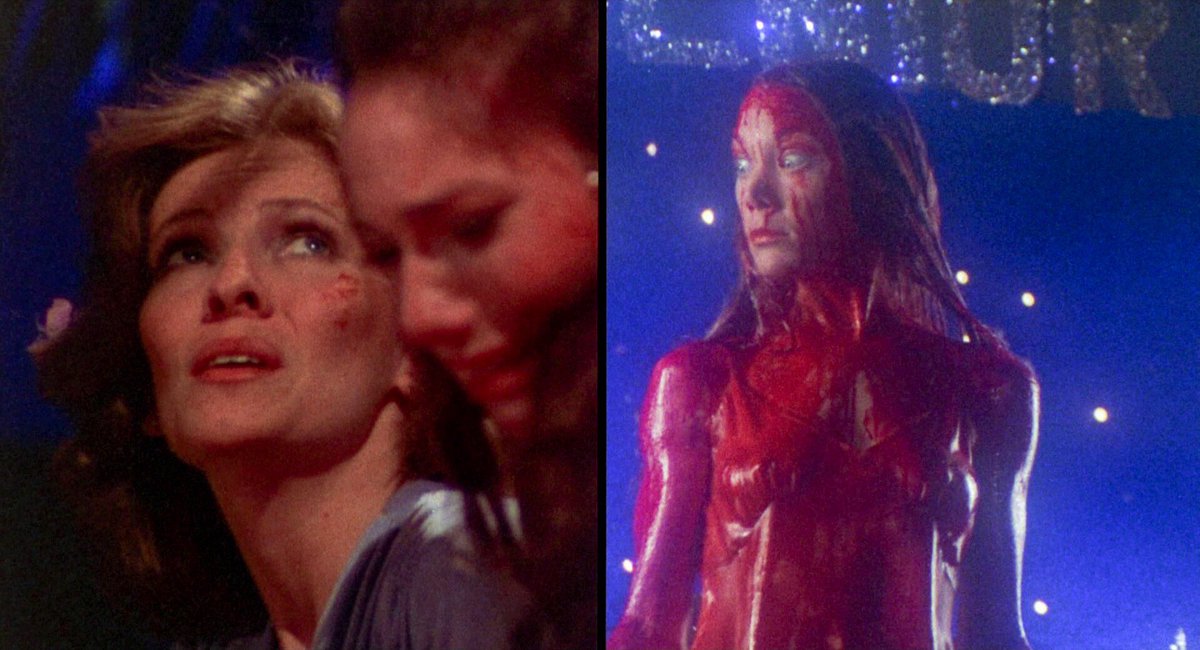

Full disclosure — nothing makes me dread a review assignment right now like the knowledge that a film shot during the pandemic also uses it as a plot point. But what in lesser hands might have been just another tiresome COVID-19 quickie, locking us into a reality we’re all desperate to escape, becomes a tautly suspenseful nail-biter in Kimi, thanks to tirelessly eclectic director Steven Soderbergh and seasoned screenwriter David Koepp. Lean, mean and enlivened by the filmmakers’ love letter to both Hitchcock and Brian De Palma, this HBO Max premiere riffs knowingly on Rear Window and Blow Out in the age of virtual assistants, all-seeing algorithms, invasive surveillance and snaky tech magnates. At a time when Facebook guru Mark Zuckerberg’s ambivalence about privacy issues and his ambitious Metaverse plans have cast him in a dubious light, it feels appropriate to make a villain out of a tech conglomerate CEO eyeing a squillion-dollar personal profit from an IPO. And it’s a sly inside joke to cast neo-illusionist Derek DelGaudio in the role of Amygdala Corporation chief Bradley Hasling, taking his company public on the strength of a virtual assistant called Kimi.

In a TV news interview that opens the film — and exemplifies Koepp’s tidy way of dispensing with exposition — we learn that Kimi has the edge over competitors like Siri and Alexa because the AI brain relies on human excellence to resolve issues on data miscommunications. Kimi’s capabilities are always growing.

A tech analyst working for the company, Angela Childs (Zoë Kravitz) lives alone in a converted Seattle industrial loft. She receives occasional role-play booty calls from Terry (Byron Bowers), a neighbor from across the street, but never leaves her apartment. Angela is agoraphobic, and like Terry, both her mother (Robin Givens) and therapist (Emily Kuroda) — seen only in Zoom calls — are growing impatient with her lack of progress. She acknowledges that while she was improving, COVID has been a setback. The trauma that sparked Angela’s condition is hinted at, though withheld until relatively late in the action.

Terry is not the only neighbor Angela observes across the way. There’s also a creepy-looking guy with a set of binoculars, who appears never to leave his apartment either, and seems far too interested in what’s going on in the surrounding buildings and on the street below. Later revealed to be named Kevin (Devin Ratray), he will play an unexpected role when Angela finds herself in extreme danger.

While reviewing flagged data streams, Angela hears the sounds of someone screaming in distress beneath blaring techno music. Like John Travolta in Blow Out, she breaks down the audio elements and forms a vivid mental picture of a woman (Erika Christensen) experiencing sexual assault. With the help of a flirtatious tech problem-solver in Romania, Darius (Alex Dobrenko), Angela traces the stream to a user and accesses her entire Kimi history, exposing the full extent of nefarious crimes that possibly include premeditated murder and go right to the top of Amygdala.

There’s little sustained mystery in Koepp’s screenplay but considerable ingenuity in the resourcefulness of Angela once she lands in a life-threatening situation and paradoxically turns to Kimi for a way out. Clever touches include making Chekhov’s gun a construction-site nail gun.

Editing under his regular Mary Ann Bernard pseudonym, Soderbergh always excels at pacing, eliminating any flab in a tight feature that runs just a brisk 89 minutes. Likewise his camerawork, as usual signed under the alias Peter Andrews, which maintains visual interest and propels the story with its probing surveillance angles, then nervously tracks Angela once she overcomes her fear enough to step outside her apartment.

Owen Gleiberman, VarietyIn case you were wondering, yes, we have been here before. Not specifically in a Soderbergh film, but in “The Conversation” (where Gene Hackman played a solitary surveillance snoop who realizes he may have recorded a murder), and in a handful of other cinematic references that Soderbergh does winking homage to: “Blow-Up,” “Rear Window,” “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” — and, in a funny way, the recycling spirit of Brian De Palma, who’s evoked through the film’s voluptuous old-fashioned musical score, by Cliff Martinez, which sounds like an homage to the Hitchcock/Herrmann homages of Pino Donaggio. Zoë Kravitz holds the screen with her cool austerity, her impassive façade hinting at heavy anxieties just beneath. When Angela uncovers video footage, through Kimi, of what those noises were, it’s disturbing in the extreme, the way that the homicides in “Michael Clayton” and “Crimes and Misdemeanors” were. We see murder in the movies almost every day, but it’s the rare film that’s grounded in the real world enough to remind us that murder is something ordinary people commit. Strung out with fear, Angela is, at long last, driven out of her apartment by the order to share her discovery with the authorities at work, who have promised to call the FBI. The lobby floor of the Amygdala office is out of a technocratic sci-fi movie (the future is here! At least in elevator banks), but it may be less scary than the people she’s reporting to.

“Kimi” marks the first time that Soderbergh has collaborated with the screenwriter David Koepp, who has long been a rock-solid mainstream talent (“Jurassic Park,” “Carlito’s Way,” “Panic Room”), and the essential design of Koepp’s script — everything about it, really — is standard issue: the isolated hacker heroine, the discovery of a crime linked in shadowy ways to corporate malfeasance, her scheme to do an end run around the conspiracy, the whole thing culminating in a last-act action face-off.

So why did I say that “Kimi” shows us a way forward? Because the fun of the movie lies in the modestly budgeted sparkle and foreboding ingenuity of Soderbergh’s direction. He’s become the Samuel Fuller of minimalist indie kicks. His filmmaking joy comes through everywhere — in the way that as the (uncredited) cinematographer, he frames each shot like a sentence in a story; in the hypnotically cryptic exchanges between The Amygdala’s CEO (Derek DelGaudio) and a black-op associate (Jaime Camil); in Rita Wilson’s insinuating small performance as a “reassuring” office manager; in the way that the camera rushes up to Angela like a stalking demon during her existential dash through a Seattle of alienating streets and embracing protesters; and in how a nail gun becomes an immensely satisfying weapon. If we’re going to wind up watching anything in our movie theaters besides Marvel fantasies, we need a return to the spirit of this kind of filmmaking. The kind that can coax thrills out of something human.

Chris Evangelista, /FilmThe minute Angela steps out of her safe haven the entire world changes via how Soderbergh, who once again serves as his own cinematographer, shoots it. The camera angles become tilted and disorienting, and Kravitz's movements seem to be slightly sped-up as if she's in a kind of semi-fast-motion. And then things get even weirder, allowing Soderbergh to shift from a somewhat simple "Rear Window"-style thriller into the world of elaborate corporate espionage and full-blown paranoia, complete with powerful, amoral people willing to do whatever it takes to stay ahead. It reminded me not just of Hitchcock's stylish work but also that of Hitchcock acolyte Brian De Palma; "Blow Out," with its main character listening in to sounds of murder, seems like a huge influence here. As does De Palma's earlier twisty horror pic "Sisters," a film fond of images of blank, non-descript apartment exteriors, and the potentially nefarious things going on behind the walls and windows. "Kimi" almost never slows down at this point, with Kravitz sprinting from one location to another, growing more and more frantic by the minute. It leads to a dynamite chase sequence through a computer server room and builds towards a grand finale with bursts of violence and tension so thick it begins to grow suffocating. But most refreshing is how Soderbergh keeps this all relatively simple. Yes, the plot grows more elaborate and fantastical, but the film itself has its feet firmly on the ground, and Soderbergh seems solely committed to giving us a quick, mid-budget, ultra-sturdy thriller with no pretensions — the type Hollywood doesn't really make anymore. This isn't the best or even most-memorable film on Soderbergh's resume, but it is a film that does exactly what it sets out to do. Best of all, the filmmaker doesn't tack on a hacky message about how we should all unplug from our devices — because let's face it, we all know that's not happening at this point.

Amy Taubin, Filmmaker MagazineDeftly written and directed, Kimi is joyously built around Kravitz’s tour de force performance, which is idiosyncratic without ever being mannered. Except for the prologue described above she is never off the screen, and until the action-packed third act, she is often alone. This is the first movie in which Soderbergh revels in color (Kimi’s fuchsia light, Angela’s blue hair, her puce sweater and burnt orange hoodie) – not primary colors as in Godard, but just as vibrant. The first time we see Kimi, she’s puttering around her loft, and Soderbergh’s camera swoops around her as Cliff Martinez’s full orchestral score suggests that there’s more going on than meets the eye, bringing a hint of Hitchcock’s Vertigo to the quotidian activities of coffee making and opening screens. A hint, that’s all, as there will be hints of Rear Window, Blow Out, The Conversation and Three Days of the Condor — just enough to remind us that the thriller genre has a pleasurable, twisty history, and also that something different is happening here because the protagonist is a woman. From the tall windows next to her desk, Angela sees two guys with eyes on her. One (Devin Ratray) might be a peeping tom; the other (Byron Bowers) is clearly a friend. Angela gestures that she’ll meet him on the street below and then rushes around scooping up her phone, keys, mask, prescription drugs and stuffing them into her purse. She gets as far as touching the lock on the front door before collapsing on the floor. The camera hovers above, like an adult bird, helplessly watching a fledgling that’s fallen from the nest. On the street, the BF shrugs and leaves for work. Later, he comes by, they have a fast fuck, and although Angela starts to strip the bed and throw the sheets in the wash even before he has time to sit up (remember when you wiped everything that came from the outside with bleach?), there’s just enough going on between them to suggest that there is hope for this relationship. Most of Angela’s relationships, however, take place on screens — mother, girlfriend, shrink, a co-worker in Romania, who greets her with an enthusiastic “Hey, Hotness.” (He’s played by Alex Dobrenko, and he’s a real find.) Catching up with work, Angela listens to streams from the day before and hears what sounds to her — and to us – like a woman screaming as she is murdered. When her bosses refuse to take this seriously, telling her to erase the tape and forget about it, she’s forced to leave her house to confront them directly, and then to flee from them through downtown Seattle, where crowds of Black Lives Matter protesters become her temporary shield, until she arrives back home, which is now anything but a safe space. This extended chase sequence seems both precisely mapped and made up on the spot, and not only this sequence, but the entire movie. A year or so from now, I’ll watch Kimi again and remember not just the panic of the pandemic, but the pleasure of movies that dazzle the mind’s eye and ear, particularly this one.

Richard Brody, The New YorkerSteven Soderbergh, who has become admirably prolific in the age of streaming, is a director of paradox. He positions himself as a classical professional who can take on any subject and personalize it with his own style and range of obsessions. But, regardless of his manifest skills and pleasures, the quality of his work fluctuates widely, depending on his connection to the subject matter. Of all current Hollywood filmmakers, Soderbergh is the most physical, the one who comes the closest to the painterly ideal of touching the image. He has long been doing his own camera work (under the pseudonym of Peter Andrews) and also his own editing (as Mary Ann Bernard), and the way that he engages with his subject evokes a bodily music, something like dance—a cinematic swing. His new film, “Kimi,” which is coming to HBO Max on Thursday, has it. This comes as something of a pleasant surprise, because the movie’s substance isn’t apparent in its foreground—it’s built as an ordinary genre piece. “Kimi,” written by David Koepp, is a killer thriller of industrial chicanery with a high-tech edge of menacing surveillance. With its focus on a cat-and-mouse game of suspicion and pursuit, it risks the impersonal efficiency of Soderbergh’s accomplished but inconsequential 2021 feature “No Sudden Move.” Instead, “Kimi,” set in the tech world of Seattle, takes its place as one of Soderbergh’s best recent films. Amid its tightly plotted action, it seethes with a rage that seems pressurized by the sealed-off grimness of the pandemic years. The title refers to a fictional new competitor to Siri and Alexa, a voice-activated domestic command device that is distinguished by the human touch—the presence of employees, rather than algorithms, ramps up the interactive system’s informational learning curve. Zoë Kravitz stars as Angela Childs, an employee of the tech firm, Amygdala, who works on correcting the “stream.” Parked at her computer in her large quasi-industrial loft, she listens to users’ flagged interactions with the device and inputs relevant information that will prevent future hiccups (the title of a Taylor Swift song, the interpretation of “kitchen paper” as “paper towel”). When Angela hears a woman’s scream on a voice stream, then listens closer and gathers evidence of a crime, she also stumbles on a misdeed within Amygdala; when she reports the event to her managers, they try to silence her—for good. In many respects, “Kimi” is a blatantly conventional thriller. Angela is set up with a convenient array of character traits, starting with the fact that she’s agoraphobic, as a result of an attack (followed by legal misconduct) that she endured. Her loft, in a big-windowed building across a narrow street from similarly bright and comfortable buildings, is seemingly devised to be both the source and the subject of surveillance. The movie’s “Rear Window”-like premise involves a mysterious man with a pair of binoculars and a boyfriend across the way, a prosecutor named Terry Hughes (Byron Bowers), whom she invites over for quick sexual encounters but can’t bring herself to go out with—because she can hardly go out at all.

In “Kimi,” the juice is in the metaphors, starting with agoraphobia as a representation of the social disturbance of life during the pandemic. When Angela does manage to go out, she wears a mask, but, oddly, she’s among the few in the film who do so—the movie is a paranoid vision on that basis alone. When she gets to Amygdala’s high-tech, high-design office, it seems sparsely populated, tamped down, and socially distanced. The awkward ubiquity of Zoom replacing in-person meetings comes through at the start: Bradley Hasling (Derek DelGaudio), the tech wizard behind Kimi, appears on TV from his garage, where he sits in front of a faux bookcase while wearing a jacket, tie, and pajama bottoms. Bradley is at the center of some underhanded business that’s hinted at early on, but it is only the first glimmer of a wide-ranging conspiracy—intended to boost the company’s I.P.O.—that Angela’s responsible actions threaten to uncover.

The nexus of tech and crime in “Kimi” packs a personal and a collective outrage at the ways in which tech companies have abandoned their civic responsibility and allowed, even fostered, propaganda—whether anti-vax or conspiracy-theorist or racist or misogynistic or anti-Semitic or xenophobic—that has got people killed. The depraved indifference in the name of stock prices finds its symbol in Kimi—not only in the way it’s managed but also in its seemingly innocent domestic presence. The blatant but forceful metaphorical condensation of world-spanning power in a conical gizmo energizes Soderbergh’s direction throughout; it appears inseparable from the physicality and the visual intensity that distinguish the movie from more routine storytelling.

Angela may be stuck in her loft and spending an inordinate amount of time at her computer, but she inhabits her domestic space with style. Soderbergh delights in the swoop and the twist of perspective as Angela sits confidently at her desk and her screen lights up with the familiar intricacies of her digital labor. He infuses the movie with space-grabbing pan shots that swivel through the loft and fill the screen with the ordinary complexity, the hidden places and tucked-away corners, the overlooked mystery of everyday gestures. Kravitz invests Angela with light-footed grace to balance the character’s principled determination. Angela struts and dances through the apartment while doing routine tasks or talking on the phone, and Soderbergh matches her vigor with shots from below or above, extreme closeups on physical contact with objects and optical connection with digital information that evoke both a passionate engagement with the world and a chilly alienation from it (in ways that are reminiscent of Brian De Palma’s “Blow Out”).

Mike D'Angelo, AV ClubParanoia has come a long way since the analog age. Gene Hackman’s professional snoop in The Conversation methodically destroyed his entire apartment searching for a bug he believed had been planted there. Nowadays, we purchase the listening and tracking devices ourselves, in the form of virtual assistants and GPS-equipped smartphones. While most of us have made our peace with trading some degree of privacy for convenience, those curious about a worst-case scenario—or just seeking some enjoyably implausible excitement—should look no further than Kimi, a new tech-heavy thriller written by David Koepp (very much in his Panic Room mode) and directed by Steven Soderbergh (returning to Unsane territory, minus the fisheye lenses). When this film is over, viewers with voice-activated smart TVs are liable to look around for the long-dormant physical remote.

It’s not as if Angela Childs (Zoë Kravitz) doesn’t understand exactly how much information these devices vacuum up. A former Facebook content moderator, Angela now works as a “voicestream interpreter” for fictional Amygdala (cutely named after the part of the brain responsible for threat assessment), responding to issues with commands given to an Alexa-style assistant called Kimi. “I’m here!” chirps Kimi (in the voice of Betsy Brantley, Soderbergh’s ex-wife) when summoned, and there’s a very relatable running joke in which it constantly responds, unwanted, to casual mentions of its name during FaceTime conversations. Things get considerably less amusing, however, when one of the streams sent to Angela for analysis turns out to be a snatch of loud music (Massive Attack’s “Inertia Creeps,” another nice touch) beneath which a woman’s scream can be faintly heard.

Apart from a quick prologue, Kimi’s entire first half is set inside Angela’s cavernous fourth-floor Seattle apartment, from which she’s been working for some time—partly due to the pandemic, perhaps (brace yourself for masks), but mostly because she’s become agoraphobic after having been sexually assaulted. During the initial lockdown, she developed a flirtation with across-the-street neighbor Terry (Byron Bowers), but can’t even bring herself to meet him at the taco truck a few feet below.

Soderbergh responds to this challenge (itself likely pandemic-related) with cinema’s umpteenth homage to Rear Window, observing Angela monitor Terry from a distance even as another neighbor (Devin Ratray) constantly watches her. The sensation of déjà vu is compounded by Angela’s efforts to extract clearer audio from the recording and determine whether she’s hearing what she thinks she’s hearing, à la John Travolta in Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (which was already a riff on Antonioni’s Blow-Up).