[Home] [How To Move The Pieces] [Rules]

[Strategy] [How To Take Notation]

Opportunities to exchange different kinds of pieces come up all the time in a

game of chess. To determine whether or not a given exchange is favorable, the

following system is widely used. A pawn is given a value of 1 point, and the

other pieces are given values in terms of approximately how many pawns they are

worth. These values are: knight 3, bishop 3, rook 5, queen 9. A king, of course,

is priceless (its "combat" effectiveness, though, is a little better than a

knight's).

In reality, piece values vary with the position and the stage of the game. The

above values are fairly accurate for endgames, where a rook is generally equal

to a minor piece and two pawns; but in the opening and middle game, a rook is

worth only about a pawn more than a minor piece. Bishops are better than knights

in most endgame positions and in middle games with open lines, while knights are

superior in closed, blockaded positions or when all the pawns are on one side of

the board. A knight supported by a pawn on an advanced outpost (fifth or sixth

rank) from which it cannot be driven away by a pawn or other minor piece has a

value close to that of a rook.

In the opening and middle game, center pawns are the most valuable and pawns on

the edges the least valuable. A doubled pawn is worth less than two ordinary

pawns, and often becomes a target for attack. A passed pawn has extra value,

which increases dramatically the farther it advances: As a rule of thumb, when

it is supported and safe from capture, a passed pawn is worth about a minor

piece on the sixth rank and a rook on the seventh rank.

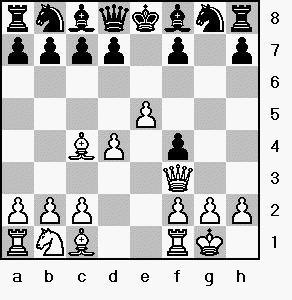

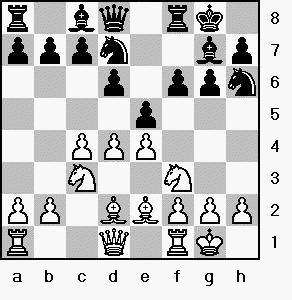

Throughout the game, players must be alert to the possibilities of

combinations that win material or, occasionally, lead to checkmate. Forks

and skewers are two of the most basic tactics; both involve attacks on two or

more targets, not all of which can be defended. In the following diagram, for

example, the White knight is forking the black king and queen, the White Queen

is forking the bishop and knight, and the White bishop is skewering the two

rooks.

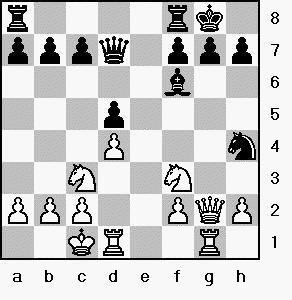

Pins are another common tactic for winning material. A piece may be pinned

against a king or against another piece. In the following position, Black's

knight cannot move without putting the king in check. Even if Black defends the

knight with d7-d6, White can win it by playing f2-f4.

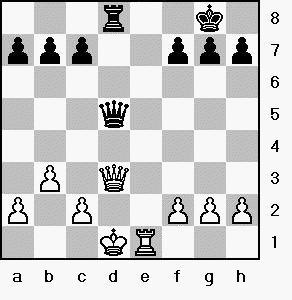

The following position shows two other standard themes, deflection and back-rank

weakness. Black seems to have an equal position at first glance, but White wins

by playing Re1-e8+. The only way out of check is Rd8xe8, after which White plays

Qd3xd5 and has an easily won game.

A common kind of interpolation is one in which an attacked piece gets away by giving check or attacking another piece. Before answering an opponent's attack on one of your pieces by attacking one of his or her pieces, be sure the piece you're attacking cannot make a new attack, leaving you with two pieces hanging. Of course, if your piece the opponent is attacking can itself give check ... well, it can get complicated (that's chess).

Openings

In the opening and for most of the game, players should attempt to control the

four center squares, as well as the 12 squares around them. On an empty board,

bishops, knights, and queens attack more squares when on a center square than

when they are near the edge. It's equally important to get your own pieces to

these good squares and to keep the opponent from doing the same. In most

openings, each player will initially take control of the two center squares of

one color. For example, after 1.d2-d4, d7-d5, White temporarily has control of

the dark squares, while Black has control of the light squares. The move 2.c2-c4

then challenges Black's light-square grip. Whether Black now takes the pawn or

defends with e7-e6 (either move is good), Black must give a high priority to

advancing a pawn to either c5 or e5. Other things being equal, if White is able

to prevent Black from playing either of these moves, White will have a

strategically won game.

The most common opening moves for White are 1.e2-e4 (King's Pawn Ending) and

1.d2-d4 (queen's pawn opening). Also popular are 1.c2-c4 (English Opening) and 1.Ng1-f3 (which most often transposes into positions similar to

queen's pawn or English openings).

In all openings, players aim to develop their pieces quickly and efficiently, on

squares where they control the center or disrupt opposing control of the center.

Usually both players will castle at an early stage, connecting their rooks, and

then bring their rooks to bear on open or half-open files.

Generally it's best to move least valuable pieces out first, most valuable

pieces last. The queen should not be moved out early, as it presents a target

for the opponent to attack. If you are forced to move your queen repeatedly

while your opponent develops several pieces, you will be in trouble.

Noncommittal moves should be made before committal moves. For this reason, the

first nonpawn move should usually be with a knight, for which the best square is

the easiest to determine. For example, when it's clear that your king's knight's

best development will be to f3 (or occasionally e2), chances are you'll still be

considering several possibilities for your king's bishop. By first making the

move you know you are going to make, you can then take your opponent's next move

into account when you move your bishop.

Don't move the same piece more than once without a good reason. Move one pawn to

open a line for each bishop, but don't move many other pawns until your pieces

are developed. Above all, fight for control of the center, as discussed above.

If the opponent has advanced pawns to the fourth rank in two of the four central

files, you must do the same to keep your share of center control.

Here are just a few samples of frequently played openings. Analyses of thousands of different opening variations can be found in numerous chess books, periodicals, and software.

|

The Ruy Lopez |

|

Sicilian Defense (Dragon Variation) |

|

Queen's Gambit Declined |

|

King's Indian Defense |

After most pieces have been developed, the game enters the middle game.

Players should continually try to improve their position by taking control of

open lines, attacking important center squares or squares near the opponent's

king, and bringing their pieces to squares where they are most effective.

When your pieces have reached their ideal squares, and not before, it's time to

move a pawn.

Every pawn move, even good moves like the advance of a center pawn in the

opening, permanently weakens the squares that the pawn had previously defended.

Unlike piece moves, pawn moves cannot be undone because pawns cannot move

backward. It's especially dangerous to advance the pawns in front of your king's

castled position. While it's common and reasonably safe to castle

on a side where a bishop is fianchettoed, or where the edge pawn has advanced one square, a castle in

which no pawn has moved is the most secure. Pawn moves around the castle should

only be made when absolutely necessary.

Pawns can be advanced to drive enemy pieces from their best squares, to open

lines of attack, and to exchange opposing pawns that are shielding the king or

other pieces from attack. As pawns are moved and exchanged, players should try

to keep their pawn structure as strong as possible. That means avoiding doubled

pawns, backward pawns, and the creation of holes--squares that a player can never attack with a pawn, and which the

opponent is likely to exploit by occupying with a piece, especially a knight.

In the following position, White's doubled a pawns are easily restrained by

Black's lone a pawn, and so are hardly worth more than one pawn. Black's e pawn

is backward, unable to advance with the support of another pawn; and a result,

Black has a hole at e6. If White can post a knight there that Black cannot

exchange off, it will be at least as valuable as a rook.

As positions simplify through the exchange of pieces and pawns, it becomes

easier to look farther ahead. Nevertheless, endgame play can be very subtle and

tricky.

In an endgame, an advantage of two or more pawns is usually enough to win

routinely. With other things being equal, being a pawn ahead is usually enough

to win when players have pawns on both sides of the board, but not enough when

all pawns are on one side of the board.

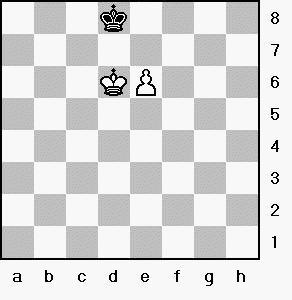

In endings with only kings and pawns, a crucial factor is often who has the

opposition. This is similar to the concept of "the move" in Checkers. If two

kings lie along the same line--a rank, a file, or a diagonal--with an odd number

of squares intervening, the player who just moved has the opposition. In the

simplest ending, king and pawn vs. king, having the opposition can mean the

difference between winning and drawing.

© David Leckner 2002