The eastern portion of southern Africa, the area known as KwaZulu-Natal, was settled at

the beginning of the 17th century by the clans who would collectively become known as

the Nguni people and, individually, as the Zulu, Xhosa, Pondo and Swazi people.

The eastern portion of southern Africa, the area known as KwaZulu-Natal, was settled at

the beginning of the 17th century by the clans who would collectively become known as

the Nguni people and, individually, as the Zulu, Xhosa, Pondo and Swazi people.

They were part of a larger group led by a chief, called Dlamini. The group was

believed to have migrated south from a legendary place in North Africa, called eMbo.

Somewhere along the way the two groups split up and chief Nguni and his group found

their way into this lovely area of rivers and hills, now known as KwaZulu-Natal.

The area was already inhabited but these people became little more than phantoms

and, according to the Zulu people, all that was left of them was their voices,

which could be heard echoing in the mountains.

They were part of a larger group led by a chief, called Dlamini. The group was

believed to have migrated south from a legendary place in North Africa, called eMbo.

Somewhere along the way the two groups split up and chief Nguni and his group found

their way into this lovely area of rivers and hills, now known as KwaZulu-Natal.

The area was already inhabited but these people became little more than phantoms

and, according to the Zulu people, all that was left of them was their voices,

which could be heard echoing in the mountains.

The name of this man might have vanished into the mists of time had it not been for his

great-great-great grandson, Senzanghakona, who presented the Zulus with a son named

Shaka - the man who would turn the Zulus into a mighty warrior nation. Because of his

extraordinary military and strategic finesse, Shaka, in the course of 12 short years,

succeeded in building a mighty Zulu nation - to this day the largest ethnic group in

South Africa.

The name of this man might have vanished into the mists of time had it not been for his

great-great-great grandson, Senzanghakona, who presented the Zulus with a son named

Shaka - the man who would turn the Zulus into a mighty warrior nation. Because of his

extraordinary military and strategic finesse, Shaka, in the course of 12 short years,

succeeded in building a mighty Zulu nation - to this day the largest ethnic group in

South Africa.

Zulu shields, made from oxhide, were used both as a protection and as a method of concealing

the weapons the warrior was carrying. To establish uniformity, the cattle owned by each regiment

were of the same colour as their shields.

Zulu shields, made from oxhide, were used both as a protection and as a method of concealing

the weapons the warrior was carrying. To establish uniformity, the cattle owned by each regiment

were of the same colour as their shields.

For example, one flat-topped mountain in the Tugela River valley was named iSabuyazwi,

“the returner of sound” because one day, as he passed the mountain, the sound of his

laughter was echoed back to him. Another notable place-naming event occurred when Shaka

led his armies down the south coast of KwaZulu-Natal.

For example, one flat-topped mountain in the Tugela River valley was named iSabuyazwi,

“the returner of sound” because one day, as he passed the mountain, the sound of his

laughter was echoed back to him. Another notable place-naming event occurred when Shaka

led his armies down the south coast of KwaZulu-Natal.

It was his brother Dingaan whom the White migrants, the Voortrekkers, encountered when they

crossed the Tugela River, the southern boundary of Zululand. In December 1838, on the banks

of a tributary of the Buffalo River, the two groups faced one another in battle after Dingaan

had ambushed and killed the Voortrekker leader, Piet Retief, and his men. Following the Zulu

army’s defeat at the hands of the Voortrekkers, the river was known as Blood River.

It was his brother Dingaan whom the White migrants, the Voortrekkers, encountered when they

crossed the Tugela River, the southern boundary of Zululand. In December 1838, on the banks

of a tributary of the Buffalo River, the two groups faced one another in battle after Dingaan

had ambushed and killed the Voortrekker leader, Piet Retief, and his men. Following the Zulu

army’s defeat at the hands of the Voortrekkers, the river was known as Blood River.

Young boys herd cattle and goats and their elder brothers assist in milking the cows. Girls clean

the huts, collect water and firewood and help in the fields. In the absence of schools, children

learn about their past history and customs by word of mouth, through story-telling. The example

set by elders play an important part in educating the youth.

Young boys herd cattle and goats and their elder brothers assist in milking the cows. Girls clean

the huts, collect water and firewood and help in the fields. In the absence of schools, children

learn about their past history and customs by word of mouth, through story-telling. The example

set by elders play an important part in educating the youth.

Married women wore heavy pleated skirts of oxhide, usually made by their husbands. Their large,

structured headdresses were constructed from coarse knitting wool that was sometimes woven into

their own hair and bound together with clay. Unmarried women favoured short hair. Pregnant women

often wore a maternity apron of antelope skin in the expectation that this would cause their

child to be born swift, agile and full of grace, just like the antelope.

Married women wore heavy pleated skirts of oxhide, usually made by their husbands. Their large,

structured headdresses were constructed from coarse knitting wool that was sometimes woven into

their own hair and bound together with clay. Unmarried women favoured short hair. Pregnant women

often wore a maternity apron of antelope skin in the expectation that this would cause their

child to be born swift, agile and full of grace, just like the antelope.

Stick fighting is a unique form of martial art and requires great skill and discipline.

Fighters carry a small oxhide shield in the left hand and a metrelong stick in the other hand.

The stick is used primarily to strike at the opponent’s head. Strength and agility are important

in winning a tournament or fight. As adolescents, Zulu boys entered youth regiments to be

prepared for the rigours of manhood.

Stick fighting is a unique form of martial art and requires great skill and discipline.

Fighters carry a small oxhide shield in the left hand and a metrelong stick in the other hand.

The stick is used primarily to strike at the opponent’s head. Strength and agility are important

in winning a tournament or fight. As adolescents, Zulu boys entered youth regiments to be

prepared for the rigours of manhood.

The man was then allowed to make a series of indirect approaches, often through his sisters.

After an initial period of playing “hard to get”, the girl was allowed to indicate her acceptance

by sending the man a gift of betrothal beads. Once her family had indicated their acceptance

and approval, the young man set up a white flag outside his hut, indicating his plan to marry soon.

The man was then allowed to make a series of indirect approaches, often through his sisters.

After an initial period of playing “hard to get”, the girl was allowed to indicate her acceptance

by sending the man a gift of betrothal beads. Once her family had indicated their acceptance

and approval, the young man set up a white flag outside his hut, indicating his plan to marry soon.

People consulted the sangoma if their own sacrifice did not have the desired results.

The sangomas were called to their profession by their ancestors and had to undergo a

period of apprenticeship after which they would be able to contact the ancestral spirits

at will and would be able to diagnose misfortune and illness. They were also able to

predict fortunes by ‘throwing the bones’. Sangomas were generally female.

People consulted the sangoma if their own sacrifice did not have the desired results.

The sangomas were called to their profession by their ancestors and had to undergo a

period of apprenticeship after which they would be able to contact the ancestral spirits

at will and would be able to diagnose misfortune and illness. They were also able to

predict fortunes by ‘throwing the bones’. Sangomas were generally female.

The beads on a sangoma’s head-dress were strung in loops to give the spirits somewhere to sit

as they spoke to her. Sangomas wielded considerable power in the Zulu society then and still do.

They often work together with traditional medicinal healers or herbalists.

The beads on a sangoma’s head-dress were strung in loops to give the spirits somewhere to sit

as they spoke to her. Sangomas wielded considerable power in the Zulu society then and still do.

They often work together with traditional medicinal healers or herbalists.

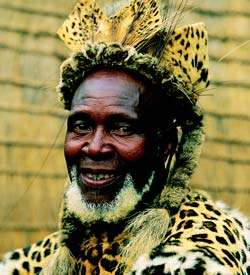

Ceremonial dress was usually an elaborate combination of exquisite beadwork and skins, pelts,

plumes and feathers. As part of their ceremonial dress, men often carried a ceremonial shield

and wore an otter skin headband, to indicate their regiment. Weapons have always been an

integral part of the Zulu tradition and to this day, men still carry different sized wooden

staffs and clubs as part of their traditional attire.

Ceremonial dress was usually an elaborate combination of exquisite beadwork and skins, pelts,

plumes and feathers. As part of their ceremonial dress, men often carried a ceremonial shield

and wore an otter skin headband, to indicate their regiment. Weapons have always been an

integral part of the Zulu tradition and to this day, men still carry different sized wooden

staffs and clubs as part of their traditional attire.

Social gatherings present dancers of the various clans with the opportunity of displaying

their skills and fitness while the onlookers accompany them by playing drums, singing,

whistling and ululating.

Social gatherings present dancers of the various clans with the opportunity of displaying

their skills and fitness while the onlookers accompany them by playing drums, singing,

whistling and ululating.

© 2002 -

"The Lone Tree Safari Lodge

All Rights Reserved"