Their Imperial Majesties, Emperor Menelik II and Empress Taitu early in their reign.

BIRTH AND ANCESTRY

Emperor Menelik II was the son of King Haile Melekot of Shewa, and Woizero Ijigayehu.

King Haile Melekot was the son of the first king of Shewa, King Sahle Selassie and

his wife Bezabish. Woizero Ijigayehu was a woman in the service of Zenebework, the

mother of King Sahle Selassie, and grandmother of King Haile Melekot. She is said to have been from Gondar, and may have been one of the people brought to Ankober, to help structure the Shewan court in accordance to the practices of the Gondar court, training young princesses in proper etiquette and behavior. Woizero Ijigayehu

never married King Haile Melekot, but King Sahle Selassie legitimized Menelik by giving

his recognition to Menelik being his grandson, and Haile Melekot, upon becoming King

recognized Menelik as his heir. Until Menelik became King of Shewa, he was more commonly referred to by his baptismal name, which was Sahle Mariam. The royal family of Shewa was decended from Abeto Yaqob,

the son of the 16th century Emperor Libne Dingel, who had taken refuge in Shewa during the

religious wars of Ahmed Gragn. Yakob's son Geram Fasil was the father of Emperor Susneyos the Catholic, and the ancestor of the Gondar line of the Imperial dynasty. Abeto Yakob's other son, Segwe Qal was the one who would found the House of Shewa. Segwe Qal fathered Werede Qal, who fathered Libse Qal, who fathered Negassi (Negassi Christos), who was recognized as the first ruler of Shewa by the various Shewan nobles and the Emperor Eyasu the Great in Gondar. All of Negassi's ancestors had held the title of Abeto. Negassi's son Abeto Sibiste (Sebastian)

succeeded his father, and declaired that he was to be refered to as Merid Azmatch, his new title. The rulers of Shewa bore the additional title of Ras. Sibiste was succeeded by Abuye, who was succeeded by his son Amhayes (Amha Yesus), who was succeeded by his son Asfaw Wossen, who was succeded by his son Wossen Seged. Wossen Seged's son however, did not assume the title of Merid Azmatch upon

the death of his father, but instead proclaimed himself King Sahle Selassie of Shewa. He was succeded by his son King Haile Melekot, the father of Menelik.

PATH TO THE THRONE

Upon userping the throne from the hapless Emperor Yohannis III (the last Gondar Emperor), Emperor

Tewodros II launched a campaign to reintegrate the various parts of the Empire under the direct rule

of the Emperor and his central authority. Shewa was his prime target. Shortly after the Emperor's

troops marched into Shewa however, the king, Haile Melekot, died of an illness he had been suffering

from for quite some time. With the death of the king, all resistance began to fall appart. The Shewans

tried to rally around Sahle Mariam (Menelik) who was only 9 years old at the time, but news arrived that the mother and

grandmother of the late king, Bezabish and Zenebework, had both gone and made their submissions to the

Emperor in order to save their property from being confiscated. Menelik and his mother Ijigayehu, along

his step-mother Tidenekialesh (widow of King Haile Melekot) and his uncle Darge were all arrested and put

in chains. When the chained prince was brought before the Emperor, it is said he was weeping bitterly.

When Tewodros demanded to know if the boy was crying because he had lost his crown and his wealth, nine

year old Menelik is said to have meekly replied "No, I weep for my father who I loved very much." Emperor

Tewodros who was known as a particularly harsh man I times was so deeply touched by the little prince, that

he ordered the chains removed from the Shewan royals, and permitted them to bury Haile Melekot with pomp.

Tewodros was however mindful that Menelik was not only the heir to the Shewan throne, but had the Solomonic

blood which allowed him to be a claimant of the Imperial throne itself. Therefore, Menelik, his mother, his

Uncle Darge Sahle Selassie, and other Shewan royals and notables were taken to the fortress of Magdalla and

imprisoned there, although comfortably. Tewodros II would grow to have a very deep affection for Menelik, and

treated him as his own son. He would eventually marry Menelik to his own daughter, Alitash Tewodros. Of the

three dowager queens of Shewa, Zenebework and Bezabish, were reinstated to their estates. The newly widowed

queen Tidenekialesh was a very beautiful woman, and Tewodros ordered her to accompany him back to Gondar.

Tidenekialesh however asked him if he would first permit her to make a pilgrimage to St. Mary of Zion in Axum.

The Emperor agreed, and she departed for Tigrai. Upon arrival at Axum however, after paying homage to the shrine,

she promptly escaped to the coast, and with much difficulty, was able to secure passage to the Holy Land. Upon

arriving in Jerusalem, Tidenekialesh, ex-queen of Shewa, widow of King Haile Melekot, and step-mother of the future Emperor of Ethiopia, entered the Ethiopian Monastery at the Church of the

Holy Sepulcher, and lived out the rest of her life as a nun. Tewodros II, upon hearing of the escape of the former Queen of Shewa is said to have remarked amusedly, "Oh Haile Melekot, what an unusual man, His wife takes holy vows, while his mother demands titles." ("Ye meest menagn,Ye Inat shumet lemagn!") Usually in Ethiopia, it is the mothers who enter convents and widows that demand portions of their husbands estates and titles. Emperor Tewodros II, recognizing the loyalty of the

Shewan population to the royal house, appointed Haile Michael Sahle Selassie to rule over Shewa, but with the

restored title of Merid Azmatch rather than king. Merid Azmatch Haile Michael would dutifully carry out the orders of the Emperor for several years. As the brother of the late king, and son of King Sahle Selassie, most of the Shewan royals and nobles found him to be acceptable. However, Abeto Seyfu Sahle Selassie, another brother of the dead king refused to aknowledge Tewodros as Emperor, or accept his appointed administration in Shewa. He led a band of guerilla fighters that roamed the Shewan countryside for years,inciting the peasantry to rebellion. Merid Azmatch Haile Michael, although very meticulous in following the Emperor's directives and paying his tribute on time, never launched an agressive campaign against his brother, and his brother returned the favor by focusing his rebellion on the Emperor rather than on the Merid Azmatch.

Menelik and other Shewan royals were taken to Magdala. Magdala was a mountain top fortress town, surrounded on all

sides by steep cliffs. Tewodros used this place as his citadel as well as a prison for those he considered threats

to his rule. His personal relations with Menelik and his uncle Darge were very warm however. Menelik was also close

with Tewodros' son Dejazmatch Meshesha Tewodros, whom the Emperor did not favour. Menelik married Alitash Tewodros

at Magdala, and met many other Ethiopian notables being held there. Tigreans, Wolloyes, Gondares, Yejjuye's, Lastas, Gojjames, virtually all the noble and princely figures from across the Empire were intered here after being replaced by Tewodros's loyalist commoners, and Menelik would grow up exposed to them all. He would also accompany Tewodros to Debre Tabor, and other traditional centers of power in the north, and establish contacts with many of the regions old nobility as well as the new Theodorean appointees. In 1865, news arrived that Menelik's uncle, Merid

Azmatch Haile Michael had finally rebled against the Emperor. Tewodros was furious, and replaced the prince with a commoner as

governor of Shewa, Ato Bezabih. The Shewan royals at Magdala were infuriated that their birthright had been given away.

They began to plot their escape. In the mean time, Ato Bezabih also rebled against Tewodros and proclaimed himself "king"

of Shewa. This brought matters to a head, and the Shewans made their move. A large feast was given by Menelik's loyal Shewan friend and fellow captive Germame Welde Hawariat at Magdala, and the

guards were given pleanty to eat and drink. Once they began to collapse with drunkeness and over eating, Menelik, his mother and several

others of his retinue stole out of the fortress. The gates were left open for them by none other that Dejazmatch Meshesha

Tewodros himself, who was eager to help anyone against his father with whom he had quarelled often. Thus Menelik of Shewa and his retinue escaped from the fortress town of Magdalla on June 30th, 1865. The Shewans entered the nearby camp of the Wollo queen

Werqitu, mother of the young Imam Amede Beshir, one of the two claimants to the leadership of the Weresek (Mammadoch) clan of Wollo.

Tewodros had siezed Amede Beshir, had him baptised as his godson, and had fought the mother of the other claimant, the rival queen Mestawat. Although bitter

rivals, both Mestawat and Werqitu were foes of the Emperor. Werqitu was not initially eager to help the Shewan prince even though his father had been a close ally. She intitially decided to send emissaries to the Emperor to inform him that the Shewans were in her camp, and that she would exchange them for her son. Tewodros however was extremely furious when he found out about the escape of the Shewans. In a towering rage,

he declared that he could understand Menelik's desire to escape, and would probably have done the same thing himself. What

truely angered him was that Menelik had abandoned his bride Alitash, and had not taken her with him. It was an insult that

the Emperor could not forgive, as it implied that the Shewans didn't regard the daughter of a userper as being good enough

for their king. Looking through a pair of field glasses, Tewodros saw that the Shewans had entered the nearby camp of his enemy

Woizero Werqitu. Perhaps if he had not been in such a passionate mood, Tewodros might have realized that he could easily have

exchanged the young Imam and his nobles for Menelik and his. Instead, he ordered the young boy and the other Wollo nobles brought

before him. In an act of cruelty that was unusual even for him, Tewodros ordered all their hands and feet to be cut off, and each

of them thrown off the edge of the cliffs around Magdala. Oddly enough, those Shewans who did not escape from Magdala, such as

Darge Sahle Sellassie were not molested at all. The Wollo emissaries who had come to offer an exchange arrived too late, and returned with the news of the death of the young Imam. The death of her son and his nobles reached Werqitu, and her grief and anger knew

no bounds. Untill the very end, she never stopped attacking Tewodros' army, and never held back aid from anyone who rebled against

him. She recalled that she had been about to betray Menelik, but that her son had died before she could make the arrangements. She is said to have commented that Allah must indeed love Menelik very much. She ordered that the Shewans were to be given every help and assistance they might need to return to Shewa. Menelik mourned the death of the Wollo notables with her, and then proceded to Shewa, where the population rose up upon hearing

of his return and began to flock to his banner.

Although Bezabih tried despirately to muster an army to oppose the return of the Royals to Shewa, his soldiers began to desert en-masse to the banner of "the son of our master". Even as Bezabih marched his army out of Ankober to meet the royalist forces in battle, it is said a woman stood on a hill top and cried out to the passing soldiers,"What are you doing, where are you going, will you really march against the son of your kind master, the son of your good king?" It is said that many more soldiers began to desert after this incident, and Bezabih recognized that all was lost as rather than fighting agains him, the soldiers and people of Shewa were pouring into Menelik's camp, weeping and ulultating, beating drums and rejoicing at the return of the heir of Haile Melekot. Bezabih sent emmissaries humbly asking forgiveness and saying that he was "only keeping the throne safe for my king". Bezabih was deposed, and Menelik was proclaimed King of Shewa at Ankober in August 1865.

Not long after his return to Shewa, Menelik established a liason with an older woman whom he refered to as his wife even though this "marriage" was not sanctioned by the church. His second wife was Woizero Bafena, a much married noblewoman from Merabete who was widely disliked and resented at court. Widely regarded as a plotting ambitious arriviste, Bafena earned the resentment of almost all of Menelik's relatives and followers. She would later act as a spy for Emperor Yohannis IV, and had ambitions for her sons by previous husbands. Menelik however also fathered a daughter Zewditu (destined to be the eventual Empress of Ethiopia) by a Woizero Abechi, and would raise Zewditu himself after her mother met an untimely death. Menelik would also father a second daughter, Shewaregga, mother of Lij Eyasu, his eventual heir. Shewaregga's mother was a woman named Desta who may very well have been a domestic servant in the service of Menelik's aunt Tenagnework or of his mother Ijigayehu. He is also reputed to have had two children by a Gurage woman named Wolete Selassie who did not survive to adulthood. Rumors persist to this day that Ras Birru Wolde Gabriel and Dejazmatch Kebede Tessema were also the Emperor's illigitimate sons, but they were never publicly aknowledged as such. Menelik did not aknowledge Shewaregga as his daughter till much later. She was first married to Wedajo Gobena and then to Ras Michael of Wollo and would bear Menelik three grandchildren, Wossen Seged Wodajo, Eyasu Michael and Zenebework Michael.

In 1868, upon the defeat and death of Tewodros, it is said that there was celebration throughout Shewa, as Tewodros had become a hated

oppressor in Shewa. Menelik did not join his subjects in their joy. It is said that he shut himself away in his rooms and wept for the

man who inspite of being a political enemy, and been like a father to him. Menelik had sent messages of support to the British, but had

not provided direct aid to them, so he did not benefit with gifts of weapons as Dejazmatch Kassa Mercha did. The most tangible benefit from the fall of Emperor Tewodros was the release from Magdalla of Menelik's much loved uncle, Darge Sahle Selassie. Menelik created Darge a Ras upon his return to Shewa. Of all the people at Menelik's court, Darge was the only one who would dare to rebuke or scold Menelik when he felt it was called for. He was always deeply respectful of Menelik as King, but he was also the stern yet affectionate uncle who could nag Menelik about paying his debts on time. He became the most influencial prince in the Shewan court.

Upon news of the Emperors

death at Magdalla, Menelik promptly claimed the Imperial throne for himself and began to use the title of "King of Kings". However, Wagshum Gobeze had

proclaimed himself Emperor Tekle Giorgis III, and Dejazmatch Kassa Mercha refused to recognize either of them. Tekle Giorgis III began

negotiations with the Shewan royals, and the other major branch of the Solomonic Dynasty, the royal family of Gojjam. He fought and removed Desta Gwalu of Gojjam, and replaced him by a rival member of the Gojjam branch of the dynasty, Balambaras Adal. In the final result, he gave the title of Ras to Adal, and also gave him his sister Laketch Gebre Medhin in marriage. With the

Shewans, he arranged for the marriage of his half-brother Hailu Wolde-Kiros to the daughter of Ras Darge, Woizero Tisseme. Just as he was begining

to feel secure that Shewa and Gojjam would come to accept his rule, Kassa Mercha of Tembien defeated Tekle Giorgis at Assam, and deposed him. Following

the defeat of Tekle Giorgis, and the coronation of Kassa as Emperor Yohannis IV, Ras Adal found it wise to submit, and recognized the new

Emperor. He was rewarded with the title of King of Gojjam and Kaffa, with the name Tekle Haimanot. Menelik set out to invade Gojjam in 1877 to challenge Tekle Haimanot's claim to Kaffa, but he had to turn back because of two attempts to dethrone him. First his paralyzed uncle, Merid Azmach Haile Michael declared himself king. The old Prince was able to march a force into Ankober and set the town on fire, but his rebellion was crushed by Menelik loyalists. Then much to his shock, Menelik hardly had recovered from this betrayal from within his family, when he was again betrayed, this time by his own wife, Woizero Bafena. She had used Menelik's seal to issue false dicrees, seized the treasure of the House of Shewa with many arms and transfered them to the fortress at Tamo. She also transfered a royal prisoner, Dejazmatch Meshesha Seyfu, Menelik's cousin and rival claimant to Tamo as well. Her intention was to put her own son from a previous marriage on the throne, removing any threat from Meshesha Seyfu as well. However, Dejazmatch Meshesha Seyfu was able to win the loyalty of the soldiers in Tamo, who turned on Bafena and ended her plot. It was suspected that Emperor Yohannis had a hand in encoraging these plots. Meshesha Seyfu and Menelik were reconciled and Bafena admitted her guilt, blaming her actions on jealousy aroused by Menelik's attentions to the lovely young Wolete Selassie who had become his mistress. Bafena, already widely hated at court was banished in disgrace. However, a temporary reconciliation between Menelik and his wife was arranged by her freinds. This attempt at reconciliation failed, largely because Menelik recognized that he needed an heir, and that Bafena was too old to produce more offspring. They were formaly separated. For a long time, when pretty young women were presented to the King, and people descreetly told him to consider candidates for his hand in marriage, or comment on the beauty of these ladies, Menelik would sadly say "You ask me to look at these women with the same eyes that once looked at Bafena?" which meant that after the beauty of Woizero Bafena, these girls paled in comparison. These happenings did not strengthen his hand against Yohannis IV. Finally, the Emperor at the head of a large army crossed into Shewa in January of 1878. Menelik decided further claims on the

Imperial throne were unwise, so he decided to submit. A delegation of priests was sent to the Emperor to inform him, and a peace was quickly negotiated.

The Submission of the King of Shewa took place in Wollo on March 26,1878. The details of the ceremony of the submission of the Shewan king was

carefully worked out. The Emperor was seated on his throne wearing his crown, and the Shewan king and his leading nobles entered the hall

carrying stones of repentance on their shoulders. They then fell before the Emperor and kissed the ground before him as guns fired in salute

and the women of Yohannis's court ulultated. Then the Emperor placed a crown on the head of Menelik, confirming his title of King of Shewa for

himself and his heirs. The Emperor also confirmed him as overlord of Wollo. In connection with this, Menelik promised to pay his annual tribute to the Empire, provide troops when needed, and eliminate all heretical teachings in his kingdom. This meant the immediate expullsion of all Roman Catholic clerics, including Menelik's good friend the Italian Father (later Cardinal)Massaia, and the French Father Taurin de Cahagne, and all Protestant missionaries. Emperor Yohannis also called a council of the Orthodox Church at Boru Meda to resolve the schisms developing in the national church. The Council of Boru Meda was convened in the presence of the Emperor of Ethiopia, the King of Shewa, the Archbishops Petros, Lukas and Matiwos, and the Echege of Debre Libanos. Emperor Tewodros had tried to stamp out the Sost Lidet doctrine by decree, but had failed, as the Shewans had returned to this creed upon the return of Menelik to his kingdom. The largely Shewan delegation of the followers of the Sost Lidet doctrine at Boru Meda held that Christ had three births, one from God the Father at Creation, the second from the Virgin at Christmas, and the third at the Baptism from the Holy Spirit. The official Tewahido doctrine held that Christ had only two births, from the Father at Creation and the Virgin Mother at the Nativity. The Baptism was a revelation of Divinity, not a Birth from the Holy Spirit they argued. The Sost Lidet they said, compromised the unity of the Holy Trinity, by implying that Christ was not fully Divine until after the baptism. This went against the teachings of Tewahido that argued that Christ had one nature that was a complete Union of the Divine and Human that was inseperable and undevidable. This was the argument that the Church had upheld since the council of Chalcedon, and which had caused the Oriental Orthodox to break with the rest of Christendom. The bishops confirmed that the Tewahido was the correct doctrine upheld by the Patriarch of Alexandria, so the Sost Lidet were ordered to recant their teachings. Those who failed to do so had their tongues cut out on the Emperor's orders "so that they may no longer poison the faithful with their heretical teachings".

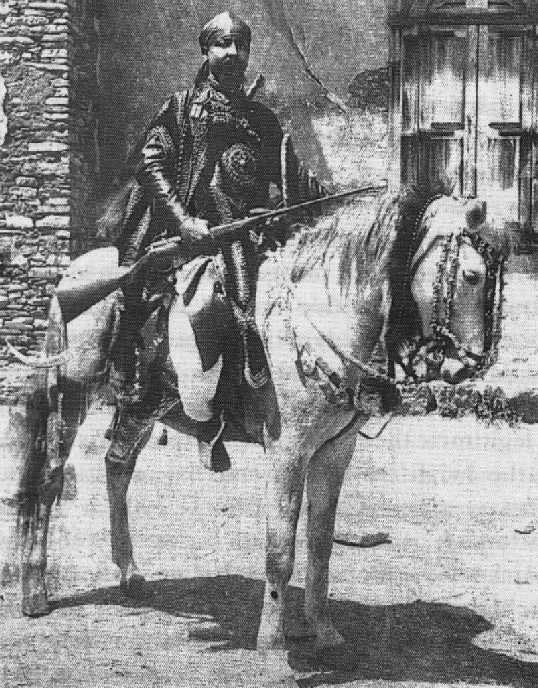

Menelik as King of Shewa

Menelik accepted all of these conditions, and returned to Shewa. However, he was not prepared to accept the designation of King Tekle Haimanot of Gojjam as king of Kaffa as well. He had long regarded the southern Oromo kingdoms, principalities and various other ethnic territories as part of his hegemonic sphere. He was determined that Shewan hegemony would continue in the south, so he marched on Gojjam. Menelik fought with Tekle Haimanot at Embabo and captured the King of Gojjam and two of his sons, bringing them back to his new capital at Entoto as his prisoners. During this time, Tekle Haimanot and Menelik for the first time speant significant time together and got to know one another. Menelik ordered that the Gojjam royals be treated appropriately with the same respect due to Shewan royals. Unexpectedly, King Tekle Haimanot and King Menelik got along famously, and formed a firm friendship that would last for the rest of their lives. Emperor Yohannis IV however, was furious. His two vassal kings had gone to war without submitting their quarrel to him first. They had fought over a royal title that he believed was his and only his to give. In anger, he ordered Menelik to bring his royal prisoners to Wollo, where he released them. He seized the weapons and booty that Menelik had captured from Tekle Haimanot and gave them back to the King of Gojjam. He also stripped Menelik of his overlordship of Wollo and granted it to his own son, Ras Araya Selassie. However, he was equally enraged with Tekle Haimanot, and in an insulting gesture, he returned the Crown of Gojjam, that Menelik had handed over, back to Tekle Haimanot in a bread basket. However, in a conciliatory gesture to the King of Shewa, he confirmed Menelik as King of Keffa, and arranged the marriage of his son Ras Araya Selassie Yohannis, to Menelik's daughter, Zewditu. This was supposed to appease Menelik somewhat for his loss of Wollo, as it was now to be ruled by his son-in-law and daughter. The two kings however were both resentful of the harsh treatment they had received from the Emperor, and began to secretly plot their eventual rebellion together.

King Tekle Haimanot of Gojjam

On April 29th, 1883, at Easter Sunday midnight mass at the Church of Medhane Alem (Savior of the World) at Ankober, Menelik King of Shewa and Keffa married Taitu Bitul. Taitu was the daughter of Ras Bitul Haile Mariam, brother of Dejazmatch Wube Haile Mariam of Simien, who was the archenemy and rival of Emperor Tewodros II, and his eventual father-in-law. Taitu was thus the first cousin of the late Empress Tiruwork Wube. Her father was the direct decendant of a daughter of Emperor Susneyos the Catholic. She was thus of Imperial blood. Bitul's mother Hirut was the aunt of Ras Ali, the last Re'ese Mekwanint and Enderase of the Gondar period who was overthrown by Emperor Tewodros II. Taitu was thus a member of the Yejju Oromo dynasty that had ruled Ethiopia and controled the puppet Gondar Emperors during much of the Zemene Mesafint period. Emperor Tewodros II's first wife Tewabech was therefore also a cousin. Although twice an in-law of Emperor Tewodros, she was the daughter of two families with a deep seated hatered of the Emperor Tewodros, and she had suffered imprisonment at his hands. Taitu's mother was Woizero Yewubdar, a minor noblewoman from Gondar. Her brother Ras Wele Bitul would become ruler of Yejju and Semien. She had a sister Desta Bitul, and another brother Alula Bitul. Wele and Alula Bitul had been prisoners at Magdalla with Menelik, and had become his good friends there. They had often spoken of their beautiful sisters, and now that Menelik was the bachelor King of Shewa, they decided to introduce him to them. Initially it is said, they had thought to promote their sister Desta as a potential wife for the King. He was introduced to her first, and after commenting on her beauty, he was then introduced to Taitu. It is said Menelik turned to Wele and said, "Why did you keep back the most beautiful for last?" Although Taitu would never have any children, her siblings and cousins had many decendents that Taitu raised, and eventually married into most of the major noble and princely families in the Empire. She would become one of the most powerful and remarkable women in Ethiopian history. With such a history, it is not suprising that Taitu would have a reputation of being a proud haughty woman. She was the ultimate aristocrat, and her dynastic credentials were the equal of any, so her pride was not just based on being the wife of Menelik, but because she was Taitu of Simien and Yejju, daughter of Bitul. She was a devout daughter of the Orthodox church, and a woman of strong conservative views. Her admirers have called her a great nationalist, a superior diplomat and negotiator, a great strategist, and the decisive half of the partnership (Menelik being famous for taking his time with dicisions). Her detractors have called her a nepotist, power-hungry and xenophobic. That she would eventually become one of the most powerful consorts in Ethiopian history is not disputed.

About the time of their marriage, the King and Queen of Shewa set about building a new church dedicated to the Holy Virgin on Mt. Entoto. Menelik built a new palace there, and then moved his official seat there from Ankober. The mountain top town was a strategic location, but it was cold, and as more people followed the court there, fire wood and water became scarce. The palace that Menelik built there was smaller and not nearly as imposing as the residence he vacated in Ankober, and was infact discribed as ramshackle by some visitors. The focus of the royal couples development plans was clearly the Church of St. Mary. It would serve as Shewa's capital only briefly. To the south of Entoto's mountainous peak was a broad hilly plateau, well wooded and intersected by the Finfine, Kebena and Akaki rivers. Near the Finfine river, were some hot springs that the Oromos had refered to as the "FinFine", a discription of the spraying action of the hot springs. These springs had given the nearby river and area their name. Taitu and her ladies began to frequently leave the cold of Mt. Entoto to bathe in the theraputic mineral springs. Her visits to this natural spa became so frequent, she built a house nearby, and was soon followed by other noblemen and women, and eventually their households. Their new houses were expanded and soon the little settlement had grown into a town as their servants and soldiers also built homes around their lords homes, and this attracted merchants. The climate was much more pleasant than frigid Entoto, wood was more widely available for fuel and building, and water was plentiful. Taitu named the new town she had founded (officially in 1887) "Addis Ababa" which translates to "New Flower". Addis Ababa would become Menelik's permantent capital, and it remains the capital of Ethiopia today.

About the time of Menelik's marriage to Taitu, an Italian embassy arrived in Shewa to establish diplomatic ties with the King. Emperor Yohannis IV, in his very liberal and federal approach to Empire, allowed his vassal kings to recieve diplomatic missions, and to carry on correspondence with foriegn governments and crowned heads on their own. With his increasingly difficult relations with the Italians, Rome found it prudent to have good relations with the kings of Shewa and Gojjam, and perhaps cultivate them as potential allies against the Emperor. With this in mind, Marchese Antinori was sent to negotiate and sign a treaty with the King of Shewa, by the Italian government. The aged nobleman died in August 1882 before he could do so, so he was replaced by his deputy, Count Pietro Antonelli. Menelik and Antonelli negotiated a treaty that granted extraterritoriality to Italians living in Shewa (they would be subject to Italian rather than Shewan criminal law) except in cases involving subjects of both kingdoms where a joint Italian/Shewan commision would judge cases. The treaty also exempted Shewan goods from duty taxes at Assab, provided for an exchange of envoys, and respect for each others religion. Secretly, Menelik was engaged in negotiations to buy guns and ammunition from the Italians in preparation for his rebellion against the Emperor. The Italians gave him a sizable loan to buy these guns as well. It was about this time that Yohannis IV wrote Menelik to inform him that the Italians had occupied Massawa, and that the British had failed to hand the port over to Ethiopia as the Emperor had expected. Shocked, Menelik summoned Antonelli and demanded an explanation. Not aware that the port had been taken by Italy, the ambassador tried to appease the King of Shewa by saying that the Italians were preferable to the English or the French as masters of Massawa as they were freinds of Ethiopia, and that Menelik should try to convince the Emperor that Italy was an ally and that it would be to his benefit to have them as neighbors. Mindful of his own secret dealings with the Italians, Menelik tried half heartedly to do this, but the warm feelings he had once had for the Italians were now tinged with the beginings of suspicion. His wife on the other hand became fiercely hostile to the Italians from this point on and became a nightmare to Antonelli in her unwavering hostility to Italian designs in the region.

The story of the Italian confrontation with Emperor Yohannis, and the rebellion of the Kings of Shewa and Gojjam against Emperor Yohannis IV is covered in the section dealing with that monarch, as well as the subsequent attack of the Mahdists and the death of the Emperor. Therefore, it will not be dealt with in this section. Never the less, Emperor Yohannis IV was killed at the Battle of Mettema, on March 11, 1889. Shortly before he died, the wounded Emperor had named his newly aknowledged son Mengesha as his heir. Northern Ethiopia exploded as various relatives of the dead Emperor began to vie among themselves for power, reaching for the Imperial throne, while refusing to aknowlege Ras Mengesha Yohannis as the new Emperor. Tigrai, Tigre, Hamasein, Akale Guzai, Serai and parts of Simien and Beghemidr were rent with disturbances and battles as the remnants of Yohannis IV's proud army disintigrated and scattered to the banners of various claimants and warlords. Of the great nobles and officials of Yohannis's court, only Ras Alula stead fastly clung to the wishes of the dead monarch and aknowledged Ras Mengesha as the legitimate monararch of the Empire.

An early photograph of Her Imperial Majesty Empress Taitu Bitul, Light of Ethiopia.

An early photograph of Her Imperial Majesty Empress Taitu Bitul, Light of Ethiopia.

Menelik of Shewa and his Queen were in Wuchale in Wello in the first week of April, 1889, when news of the death of the Emperor reached them. Count Pietro Antonelli had just arrived with a fresh shipment of weapons from Italy. Menelik saw that this was finaly his moment. Through Antonelli, Menelik formally asked the King of Italy and his government to sieze the town of Asmara and all of Hamasein to weaken Mengesha Yohannis and any other northern claimants. He then sent out messengers throughout the Empire, to Beghemidir, to Gojjam, to all of Wello and to Tigrai and the north, to Harrar, to Wellega, to Keffa and Sidamo, to Gemu Goffa, to Arsi, to Bale and Illubabur calling for oaths of loyalty to "Menelik II, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God, King of Kings of Ethiopia. One by one the nobles, cheifs and lords of the Empire began to flock to his banner. Ras Michael of Wello was the most hesitant. He had been at Yohannis's side at Mettema and perhaps had qualms about deserting his son. He did finally decide to pledge alliegence to Menelik. King Tekle Haimanot of Gojjam also sent his messages of recognition, and in return, Menelik re-confirmed him as King of Gojjam and Damot. Quickly, Menelik signed a treaty with Italy, with Count Antonelli signing it for King Umberto. The Treaty of Wuchale gave recognition to an Italian Colony in the north that they intended to name Eritrea. The town of Keren was occupied on June 2nd, and Asmara on August 2nd. This was done to undercut the power base of Ras Mengesha. It was a decision by Emperor Menelik which would have dire reprecussions to this very day. There was the even more explosive bomb hidden in Article 17 of this same treaty.

Menelik, around the time that he was proclamed Emperor and King of Kings.

Menelik, around the time that he was proclamed Emperor and King of Kings.

Article 17 of the Treaty of Wuchale (or as the Italians spelled it "Uccialli") was to have huge consequences. In the amharic version, it stated that The Emperor of Ethiopia could avail himself of the services of the government of the King of Italy in his dealings with the powers of Europe if he so wished. A harmless clause. The Italian version of the same clause 17 stated that the Emperor of Ethiopia "consented" to use the government of the King of Italy for his contacts with the powers of Europe. This was phrased as a requirement that made it compulsary. It established an Italian protectorate over Ethiopia. At the time however, the Ethiopian side was unaware of this. It was an old trick used by colonialists to entrench themselves that had been used before elsewhere in Africa. Treaties were often signed by kings, chiefs and elders not realizing the legal ramifications. In Ethiopia though, due to the carefull court diplomacy that existed in the Empire for centuries, the deception of mistranslation was employed. Unaware of what had happened, the new Emperor prepared for his coronation, and duly notified the monarchs of Europe of his accession to the Throne of Solomon. Letters were sent to Queen Victoria of Great Britain, King Umberto of Italy, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany and President Carnot of the French Republic. These letters would prove to be the time bomb that would explode in Antonelli's face. In the mean time, Menelik sent his cousin Dejazmatch Makonnen Wolde Michael(later Ras) to Rome to observe the Italian ratification of the treaty of Wuchale. Makonnen was the son of Woizero Tenagnework Sahle Selassie, daughter of King Sahle Selassie, sister of King Haile Melekot, and aunt of Emperor Menelik II. Athough there is a long tradition in Ethiopia of monarchs holding their close relatives in deep suspicion, Menelik never had any towards Makonnen. Makonnen grew up in Menelik's household, and was close to him. Menelik trusted him as he trusted few others, and treated him as a younger brother or son. Makonnen whole heartedly returned his cousin's affection, and would serve him loyaly for many years as his de facto Foriegn Minister, diplomat, domestic negotiator, and general. Ras Makonnen's son would eventually become Emperor Haile Selassie I. Dejazmatch Makonnen went to Italy and was treated to a tour that accentuated Italian might. He was given tours of military instalations, watched military drills, toured factories and munitions depots. He was recieved by the Premier Crispi, and by King Umberto and Queen Margarita as well. For his visit with the royal couple, he was taken from his hotel in a royal carriage to the Venezia Palace. In the Ethiopian manner, he bowed to King Umberto from the door to the Throne Room, walked half way to the King and bowed again almost to the floor, and then went down on his knee and pressed his forhead to the floor when he reached the king. He was impressed with the granduer of the Palace, of Rome and Naples, and the strength and sophistication of the Italian military. Although he had met many Europeans in his life, Makonnen must have been overwhelmed by the technological advancement of Europe. However, the purpose of the visit was the Treaty of Wuchale, which came up before the Italian Parliament and was ratified. Before it was ratified, Ras Makonnen was persuaded to sign an additional convention to the Treaty on October 1st, 1889, at Naples, that fixed the boundry of the Italian territory as of the de facto position of Italian troops on that very day. What the Prince did not realize, but which the Italians knew very well, was that the Italian army, taking advantage of the weakness of Ras Mengesha and war torn Tigrai, had marched deep into Tigrai and occupied numerous localities that had never been ceded in the original treaty. He also didn't know that on October 11th, 1889, Prime Minister Crispi had officially notified, by letter, twelve European governments, and the United States, that as provided by Article 17 of the Treaty of Wuchale, "..in all matters dealing with other governments, the Empire of Ethiopia would be represented by the Kingdom of Italy." An Ethiopian student then residing in Rome named Afework Gebre Yesus (who would play a role in Itlian affairs in Ethiopia through 4 reigns) came to Makonnen's hotel suite and insisted on seeing the Prince. He then showed the Prince an article in an Italian newspaper that stated that Ethiopia had become an Italian protectorate. A suspicious Makonnen asked Count Antonelli who had traveled with him to explain this. Antonelli told the prince that Afework had a poor understanding of Italian. Ras Makonnen accepted this at face value. Unable to read or understand Italian, all he had before him was the Amharic version of the Treaty that did not establish a protectorate. Thinking all was well, Dejazmatch Makonnen returned to Ethiopia.

Emperor Menelik II was crowned as Emperor on November 3rd, 1889. He was crowned at St. Mary's Church on Mt. Entoto by Abune Mattiwos who now assumed the senior possition in relation to Abune Petros who had crowned Emperor Yohannis and remained in northern Ethiopia. Two days later, Emperor Menelik crowned his wife as Empress Taitu, "Light of Ethiopia". The celebrations were magnificent, and thousands assembled to pay their respects to the new monarchs. Ethiopia was not trouble free however. Ras Mangasha and Ras Alula still refused to accept Menelik as Emperor. A huge epidemic among the cattle in the Empire had decimated not only the sources of beef and mutton, but also the animals used for transporting food and plowing fields, resulting in widespread famine. In December of 1889 Menelik marched north to impose order on Tigrai and recieve recognition from the still rebellious Ras Mangasha and Ras Alula. On arriving in Tigrai, he found that the Italians had advanced much further than the boundry set down in the Treaty of Wuchale, and that on January 29th, 1990, the Italians under the command of General Orero had occupied both Adowa and Axum. Ras Mangasha and Ras Alula, greatly weakened by the famine and the infighting with the other Tigrean lords were helpless to stop them. Nevertheless, Emperor Menelik marched into Mekelle and on February 23rd, he presided over a ceremony of submission in which the nobility of Tigrai came forward to pay him homage and recognize him as the legitimate Solomonic Emperor of all Ethiopia. Ras Mangasha sent messengers saying he would submit in 20 days. Menelik agreed to allow him time, aknowledging that Ras Mangasha was entitled to a seperate ceremony as he was the son of an Emperor. His primary concern at the moment was his anger over the occupation of Adowa and Axum by General Orero. The general sent messages assuring the Emperor that his occupation of these towns was to bring stability and feed the starving masses, not to conquer territory. The Emperor was somewhat appeased by the arrival of Dejazmatch Makonnen from Italy, with a fresh and large supply of weapons purchased from Rome. It was at this point that Makonnen told the Emperor of the convention that he had signed in Rome that had fixed the borders to the position the Italian army held at October 1st. Much to the horror of Menelik and his officials, it was learned from the Tigreans that the Italians had advanced far beyond the boundry set down in the Treaty of Wuchale by that date, and that in all likelyhood, they had played a nasty trick on Makonnen. The Tigreans were especially angry, and many in Menelik's circle were upset with Makonnen and gossiped about bribery. The Emperor however knew Makonnen much better, and did not hesitate to elivate him to the title of Ras, and enlarge his governorate of Harrarge. The Italians withdrew from Adowa and Axum, but did not move back further than their lines as they were on October 1st. They agreed to discuss the issue of the borders further. Count Antonelli had returned to Ethiopia with Ras Makonnen, and tried to convince the Emperor of the need to accomodate the Italian desires as far as the borders in the interests of keeping the Tigreans pacified. Menelik returned to Shewa with Antonelli continuing to make a case for the Italian side. Menelik was not very convinced. Antonelli also announced the appointment of a new Italian representative in Ethiopia that would be replacing him. He was Count Augusto Salimbeni, a gossipy Italian aristocrat and engineer who had worked for some years building a bridge and other projects for King Tekle Haimanot in Gojjam. His tenure would be disasterous from the very start. Just before his official ceremony of presenting his credentials at Menelik's palace at Entoto, he was thrown from his mule after having donned his official diplomatic court atire. He arrived shaken and soiled, and much to his anger, recieved a rather casual informal reception, which may have been a calculated display of royal disfavor at recent Italian actions on the border. The count was not even offered the customary glass of Tej (honey wine). No large army awaited him to march him up to the palace, no great fanfare, no beating of drums or blowing of trumpets. In relation to the elaborate ceremony and pomp that usually surounded the reception of the representatives of foriegn monarchs, this reception seemed unusually frugal. Salimbeni called the reception "disgusting". Nevertheless, Salimbeni agressively promoted the Italian desires for the border between Ethiopia and the new Eritrean colony. He was busy with these arguments and almost as an after thought, handed over letters that he had brought with him from Europe that had been sent to Emperor Menelik from Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, Queen Victoria of Great Britain, King Umberto and Queen Margarita of Italy, as well as Prime Minister Crispi and Signor Pisani. The European leaders were following what the Italians had informed them about the Treaty of Wuchale, and were carrying out their contacts through the Italian representative. It was Queen Victoria's letter that would take the trouble over the Treaty of Wuchale over the brink. In her letter, the British Queen acknowledged the accession to the Ethiopian throne of Menelik, and his desire to send representatives to England and France. However, she also noted that as the Emperor of Ethiopia had consented to "avail himself of the government of Italy" for all his contacts with foriegn governments according to the Treaty of Wuchale, she had sent "..our friend, the King of Italy, copies of Your Majesty's letter and of Our reply." This letter, once translated a few days later, caused a reaction of such fury on the part of the Ethiopian monarch that it took Salimbeni and his staff quite by suprise. Unlike the departed Antonelli, Salimbeni was completely unaware of the differences between the Amharic and Italian versions of Article 17, and was bewildered. Menelik wanted to know what this meant. He had never agreed to give Italy control over his relations with other governments. With the Tigrean/Eritrean border question added on to this issue of Italian assumption of a Protectorate, tempers had risen considerably. Empress Taitu is said to have asked her husband in anger "How is it that Emperor Yohannes never gave up a handful of our soil, fought the Italians and the Egyptians for it, even died for it, and you, with him for an example, want to sell your country! What will history say of you?" Emperor Menelik II of course had no intention of selling anything. He summoned the Italian diplomat and said to Salimbeni "This country is mine and no other nation can have it. I thought we had settled everything....you asked for more and I gave you all of Hamasein. Now you want more?". Things were about to get uglier. Hours of attempted discussion on the matter turned into days, into weeks and into months. When the Italians realized that they were running up against a brick wall they began to look for other alternatives or potential leverage. In the north, General Orero attempted to make a seperate deal with Ras Mengesha Yohannis in Tigrai over the border. Once he had submited to Menelik however, Ras Mengesha informed General Orero that it was not his place to give what belonged to the Emperor of Ethiopia, and that he had naturally informed His Imperial Majesty of all that had been discussed between him and the Italians. Around the same time, in an attempt to foment sympathy for Italy among the muslims of Ethiopia, an Italian regiment occupied Ausa to "forestall the French" who they claimed were considering occupying the Afar sultanate. The Emperor quietly and simply, but very angrily stated "Ausa is mine!" to Salimbeni. Salimbeni notified his superiors in Rome of the disintigration of his situation. Labled an "alarmist" and "inept", Salimbeni's image with the Italian Foriegn ministry took a beating. The fact was however that the Italians could not manipulate Menelik to do as they disired, and this was not Salimbeni's fault. As the beaurocrats in Rome saw it, Salimbeni was a failure because he couldn't manage to handle matters with what they regarded as a state of savages run by savages. As things were taking a turn for the worse as far as Ethio-Italian relations, it was decided in Rome that the only one that could salvage this disaster that was increasingly being blamed on Salimbeni's inept handling, would be Count Pietro Antonelli. Antonelli arrived at Entoto on December 17th, 1890 with letters from King Umberto that tried to appease the Emperor in very patronizing terms. Antonelli tried to blame the mistranslation of Article 17 on the Ethiopian translator, Yosef Niguse. He offered to undo the jist of the article if the Emperor promised not to accept the protection of any other power. When asked to put this in writing, Antonelli came up with "..in the event that Ethiopia might ask for a protectorate, she would give preference to Italy" which Menelik found unacceptable and angered Empress Taitu even more. Emperor Menelik proposed the wording "Italy makes it known that the Empire of Ethiopia is not its protectorate, and the Emperor will refuse to any other power such a declaration." Menelik also set down what he believed would be an acceptable border on a map. Antonelli was increasingly frantic. He canceled the cost of the freight on weapons that Menelik had purchased from Italy, and agreed to pay for the import of grain for the starving people in Tigrai that Menelik had requested. He gave in on several points on the border question, recognizing that Digsa and Gura would be firmly on the Ethiopian side of the border, and Ethiopian sovreignity over the monastery of Debre Bizen and all affiliated monasteries in Eritrea with their estates and land holdings. This was all done in hopes of molifying the Emperor into accepting Article 17, and Italy's prefered border. Empress Taitu proved to be his biggest obstacle as far as Article 17. She stuck by the demand to have it completely abolished from the treaty, even as her husband considered freezing it as it was in Italian and Amharic for five years until the treaty was due for review. Antonelli argued that the Italian text could not be changed without Italy losing dignity. The Empress coldly replied "..we too must maintain our dignity!" Antonelli then handed a letter of recall to Salimbeni basically fireing him, as if the whole fiasco was completely Salimbeni's fault. He also anounced his own intention to leave with Count Salimbeni, signaling the offence he had taken personally and on behalf of his King and country. Menelik suddenly became concerned and concilliatory. He said he had decided to agree to some Italian demands in order to save his freindship with Italy. Antonelli withdrew his threat of departure and withdrew the dismissal of Salimbeni. Menelik then sent over a letter in Amharic for Antonelli to sign. He assured Antonelli that the two texts of Article 17 could remain as they were for five years, and that Ethiopia would certainly call on Italian assistance in foriegn affairs "out of friendship" but not out of force. During these discussions, Count Antonelli may have used the Amharic word "Yikir" meaning "let it remain" but which can also mean "leave it out" which may have been misinterpreted either intentionally or mistakenly by the Ethiopians as applying to article 17. Count Antonelli happily signed the letter thinking he had pulled a major diplomatic coup. He boastfully commented to his staff that the only way to deal with "these people" was with firmness. When the Imperial translator, Gebriel Gobena failed to provide a timely Italian translation, Salimbeni decided to attempt a translation of the new Amharic agreement into Italian himself. Much to his horror he found that Count Antonelli had signed a document that said that Article 17 was canceled and abrogated (left out ie, "yikir") instead of left as it was till the time of renewal. It looked like Menelik's payback for being tricked into signing a clause in Italian that handed over his Empire into Italian protection, and indeed, it may very well have been. Antonelli went into a towering rage. He stormed to the Palace and demanded and audience. The Imperial couple were at lunch with Ras Makonnen and Ras Mengesha Atikem of Agew Midir, and it was Ras Makonnen who came out to see what was wrong. Antonelli ranted at Ras Makonnen against "such treachery". Ras Makonnen asked him for the letter to show the Emperor. Before handing him the letter, Antonelli tore off his signature, and in the process, tore the Emperor's seal off as well. This act angered the Ethiopians as childish behaviour, and Ras Makonnen was visibly furious at seeing the Italian tear off the seal of the Emperor of Ethiopia. Entering the presence of the Monarchs and Ras Mengesha Atikem in Makonnen's wake, Antonelli demanded justice, holding up the torn letter. Menelik coldly informed him that the letter was identical to thier discussions which Antonelli denied. He then began to heap abuse on the Imperial translator, Gebriel Gobena, but was curtly interupted by the Empress who told him he had no right to scold the translator, as Gebriel "...is our servant, so it is our place to punish him if he is in the wrong, not yours!" The Empress then asked Antonelli to show her where in the Amharic version of Article 17 of the Treaty of Wuchale the establishment of Italian Protectorate over Ethiopia was. As he could not, Ras Makonnen (who had also been tricked into signing an agreement in Rome on the borders) tartly informed him that the Amharic note that he had been sent and that he had signed meant exactly what it said, that Article 17 was abolished and canceled. The Italian diplomats realized that the Ethiopians had just given them a taste of their own medicine. Antonelli demanded back the map that he and Menelik had made notations on about the border. Menelik stated that he would return it to the Italian government. Antonelli replied that in Ethiopia, he was the government, and that if they weren't returned to him, he would consider the maps stolen. The Italians stormed out in a huff, and decided that they should suspend talks and withdraw. The Ethiopians at court were aghast at their display of bad manners. Antonelli wrote an official letter of goodbye and announced that they were all leaving. He sent messengers to various other official Italians in the Empire to assemble together as they would all be leaving with him. Ras Makonnen informed them that they were behaving like children. Antonelli returned to the Palace for his departure audience and was recieved by the Emperor. He pomposly declaired that Italian troops would remain at the border lines that they were on as of October 1st, that no financial concessions on Ethiopia's debt to Italy would be made, and that Italy would uphold and defend Article 17. Emperor Menelik responded quietly "Gidyelem", which translates roughly to "No worries! So be it." The Italians withdrew on February 11th, 1891. Emperor Menelik then issued a proclamation asking the people of the Empire to contribute what they could towards paying back the financial debt to Italy. The response was emense. During the years of horrendous famine, Menelik had forgiven debts and ordered the suspension of tax collection in hard hit areas. The public had started saying that Menelik was less like the stern father-figure monarch, and more like a compassionate mother, and had started refering to him as "Immiye Menelik" which was a nick name that translates as "Beloved Mother Menelik". It was a reputation for mercy and compassion that would spread and strengthen, and Menelik is still popularly refered to as "Immiye" to this day. People donated from what little they had to make sure that their Emperor was not degraded before foriegn princes. Much to the Italians discomfort, a year later, in 1892, the debt had been paid back in full along with all interest owed. Again the Italians tried to foment trouble by negotiating secret agreements with Mengesha Yohannis, encouraging his pretentions to the throne. On December 8th, 1891, Mengesha met General Gandolfi at the Mereb river and swore oaths on a bible and cross to "love each other's friends and hate each other's enemies". General Gandolfi and the other Italian colonial officials in Eritrea saw Mengesha Yohannis as the key to fomenting disunity in the Empire. However, the officials in the Foriegn Ministry in Rome still sought to court Menelik. In order to try to win back some of Menelik's trust, the Italian Foriegn ministry notified him of Mengesha's secret meetings with Gandolfi and the oaths. They thought that this would win them favor with Menelik while at the same time encourage disunity by angering him against Ras Mengesha. Menelik decided that two could play at devide and conquer, so he notified Ras Mengesha that the Italians had violated their Christian oaths and betrayed him. They had revealed all the details of his agreements with them, that they could never be trusted, that they were the enemies of Ethiopia, of his late father Emperor Yohannis, and of Mengesha himself. Ras Mengesha was horrified at the fact that the Italians had betrayed him to Menelik in such a manner. Instead of getting the two to fight each other, the Italians had brought them closer together, and in fact had made in Ras Mengesha, a permanent enemy. Dr. Traversi, a long time Italian medical practioner in Ethiopia returned twice in 1891 and 1892 to Ethiopia to try and revive talks. Salimbeni returned in 1892 to Harrar to discuss the loan repayments with Ras Makonnen, and try to weaken the prince's ties to Menelik, which predictably failed. The Italians sent sizable bribes and gifts to various nobles and chiefs in the Empire trying to buy them off and set them against Menelik. Little did they know that these nobles were informing the Emperor of all their communications with the Italians. The Emperor had instructed them to continue recieving the bribes and gifts, but to inform him of everything. In June, 1894, Dr. Traversi was due to leave permanently and the Italian government sent Colonel Federico Piano to replace him. He arrived at the Great Guibi Palace in Addis Ababa to present his credentials to Emperor Menelik. The Emperor recieved him with the lower part of his face covered under his cape(a sign of great displeasure). After Piano was presented and made his elaborate bow before the Emperor, the first thing Menelik asked him was "When will you be leaving?" When Piano replied "When your Majesty wishes it." the Emperor then coldly suggested "Why not leave with Dr. Traversi tomorrow then." Relations with Italy were thus severed. Traversi would return in 1894 with the last shipment of ammunition that Ethiopia had purchased from Italy. He recieved a very cold reception, and did not stay very long.

Ras Makonnen Wolde Michael, Governor of Harrar, de facto Foreign Minister, Cousin of Emperor Menelik II, Father of Emperor Haile Sellasie I.

Ras Makonnen Wolde Michael, Governor of Harrar, de facto Foreign Minister, Cousin of Emperor Menelik II, Father of Emperor Haile Sellasie I.

Menelik went about strengthening both his domestic and international situation. In 1891, he recieved Vasili Mashchov, who brought with him a letter from Czar Alexander III and two Russian Orthodox priests. The Czar had sent gifts to the Emperor and Empress, and much was made of solidarity between Orthodox monarchies. In 1892, the Russians set out on their return trip to St. Petersburg with letters and gifts from the Emperor of Ethiopia, and a request for arms and support against Italian intreagues. Also in 1892, a correspondent with "Le Temps" named Casimir Mondon-Vidailhet, who was also a semi-official representative of the French government arrived. The French were eager to thwart the Italians in east Africa, and awarded Emperor Menelik the Grand Cordon of the Legion of Honor. Friendly relations were firmly established with the French. In 1892, Menelik arranged for the marriage of his daughter Shewaregga Menelik to Ras Michael Ali of Wollo. Ras Michael was once the ranking moslem noble of Wollo, named Mohammed Ali, son of Ali Abba Dulla, and a decendent of the Prophet Mohammed. He had been converted to Christianity upon the orders of Emperor Yohannis IV, who had stood as his god-father, and whom he had served loyaly. He had been with Yohannis when that Emperor had died at Mettema. Now he had become the son-in-law of another Emperor. Michael and Shewaregga would become the parents of two children, Zenebework Michael, and Lij Eyasu, who would eventually become Menelik II's heir. In February 1894, King Tekle Haimanot made his first visit to the Emperor since Menelik had assumed the Imperial throne. He was fetted and honored continuously while in the capital, and recieved a new crown from the Emperor. Then on June 9th, 1894, Ras Mengesha Yohannis arrived along with Ras Alula and other Tigrean nobles to formally submit to Menelik II at Addis Ababa. To tie the Tigreans to them securely, Empress Taitu arranged for her neice, Woizero Kefey Welle to marry Ras Mengesha Yohannis. Menelik II had consolidated his rule, and was strengthening his house. Not long afterwards, news arrived of the shooting of the French President Carnot by an Italian anarchist. Menelik pointed to the treachery of Italians and ordered that a wreath in his name be placed on the President's grave. Always a monarchist however, Menelik also made a point to send a letter of condolence to the newly widowed Countess of Paris on the death of the claimant to the French throne, the Count of Paris.

Ras Mengesha Yohannis of Tigrai

Ras Mengesha Yohannis of Tigrai

Relations with Italy were souring further. In May of 1895, Engineer Luigi Capucci, a long time Italian resident of Ethiopia was arrested for spying after on of his couriers informed on him. A jury of male Europeans was assembled (Europeans had the right to be judged by fellow Europeans under many of the treaties they signed in Ethiopia). The five Frenchmen, two Armenians, and one Greek found him guilty, and recomended to the Emperor that he be placed under house arrest, but not harmed, as this mercy would bring the Emperor great credit in Europe. One of the Frenchmen however, Mondon-Vidailhet himself no less, told the Emperor that normal practice in France was to shoot spies. The others criticized him for condoning the death of a fellow white man at the hand of blacks. Capucci was not shot however. Another Italian, Pietro Felter was expelled from Harrar. However, the Italians had been able to march deep into Tigrai and had Ras Mengesha on the defensive. Little by little they pushed the prince out of his province. The year 1895 was a year of feverish preparations for war. Menelik re-enforced the army of Ras Mengesha, and established an arms depot at Werre Illu in Wollo. War was now unavoidable.

In December of 1893, Francesco Crespi returned to the post of Prime Minister of Italy, taking the position of Foriegn minister as well. As his undersecretary for Foreign Affairs, he appointed none other than Count Pietro Antonelli. Also appointed as the new military governor of Eritrea was General Oreste Baratieri. Now in 1895, with the deep advances into Tigrai under his belt, General Baratieri arrived for a triumphal visit to Rome. When he visited the chambers of the Italian Parliament on July 26th,1895, the parliamentary body gave him a thundering standing ovation and he addressed them as a conquering hero. King Umberto recieved him in audience, and praised his "triumph of civilization over barbarism" and Baratieri went so far as to state in one speech that he would bring the Emperor of Ethiopia to Rome in a cage. He said that there would be war by October, but with his 10,000 "civilized" troops, he would easily crush the 20-30,000 "savage" army of the Emperor of Ethiopia. He was granted funds to raise an additional 1000 troops from among the "natives" of Eritrea. He was the toast of Rome, and was the much sought after guest of every salon of every host and hostess. The Italians were confident that they were about to get a significant prize in the great European scramble for Africa.

On September 17th, 1895, the great negarit war drum on the grounds of the Palace was beaten continuously beginning at dawn. It was the signal for a declaration of war, and the population streamed to the palace gates. Imperial flags and war penants streamed over the walls of the palace. Preists, soldiers, merchants, commoners, nobles all assembled before the main gates of the palace. On the battlements above the gates appeared the Afenigus, the official who acted as the Emperor's spokesperson. He read the following proclamation in the name of Menelik II.

"Assemble the army,beat the drum (Kitet Serawit, Mita Negarit!). God in his bounty has struck down my enemies and enlarged my Empire, preserving me to this day. I have reigned by the grace of God. As we must all die someday, I will not be afflicted if I die, but enemies have come who would ruin our country and change our religion. They have passed beyond the sea that God gave us for our border. I, aware that herds were decimated and people were exhausted, did not wish to do anything until now. These enemies have advanced, burrowing into the country like moles. With the help of God, I will get rid of them. Men of my country, up till now, I believe I have never wronged you, and you have never caused me sorrow. Now, you who are strong, lend me your strong arms (your might), and you who are weak, help me with your prayers, while you think of your children, your wife, and your faith. If you refuse to follow me, beware. You will hate me for I shall not fail to punish you. I swear in the name of Mary that I will never accept any plea of pardon. Men of Shewa, asemble and meet me at Were Illu, and may you be there by the middle of Tiqimt(October). So says Menelik, Elect of God, King of Kings!"

With this, in every little hamlet and village, in every house great or small, the men of the Empire prepared to answer the call of the Emperor. As the date of the mobilization to Were Illu approached, more and more men began to leave homes with what weapons they had to report to their regional chiefs and lords who would lead them to war. The Italian Dr. Narazzini who lived at the port of Zeila reported that some terrible catastrophe of a national scale must have occured as the women were packing the churches weeping. He naively transmitted the intelligence that the Emperor had been struck by lightning and was either dead or paralyzed, a rumor that may have been deliberately planted in his ear. The truth was that the women were praying for the safe return of their husbands and sons. The Emperor, the Empress, and a large number of not only the male members, but female members of the court departed Addis Ababa marching north. Ras Darge was proclaimed Regent in the absence of his nephew the Emperor and remained in Addis Ababa.

In Italy, General Baratieri was informed that Ras Mengesha Yohannis, newly re-inforced by troops from the Emperor, had taken up possitions at Debre Hayla, very close to the Italian garrison at Adigrat. The General made haste and returned to Eritrea. He proceeded to occupied Adigrat and engaged Ras Mengesha in battle on October 9th. The Ras was defeated and began a retreat. The Italians surged forward, occupying the mountain fortress of Amba Alage. At Amba Alage, they found Ras Sebhat Aregawi, the head of the aristocratic House of Sabagadis, and ruler of the Agame district, long time rivals of the Tembien family of Emperor Yohannis for precidence in Tigrai. He had been imprisoned on the Amba by Ras Mengesha, and now offered to join the Italians in fighting him. A Major Paulo Toselli was put in comand of this fort along with Ras Sebhat and his relative, Dejazmatch Hagos Taffari. Another prominent Ethiopian on the Italian side and Amba Alage was Sheik Tohla Bin Giafer of Wollo, who had fled Ethiopia to the Sudan years before rather than submit to Emperor Yohannis IV's edict that all the Muslims of Wollo should convert to Christianity. He was here now to incite the Muslims of the empire to rise against the Emperor Menelik II and support the Italians who promised freedom for the Moslems. The Sultan of Ausa was also courted and he assured that Italians that when the oportunity arose, he would rise in rebellion and attack Menelik from the rear as he fought the Italians. The Italians had occupied Mekele as well, evacuated the priests at the Inde Yesus church on the mountain of the same name over the town, and turned it into a fortress. Ras Mengesha and his defeated forces retreated out of Tigrai and into Wollo in defeat taking refuge with Ras Michael.

The Emperor, the Empress and their court, along with their respective armies, arrived at Werre Illu 18 days after they left Addis Ababa. They left the capital with 50,000 troops, but by the time they reached Werre Illu the army had swollen to 150,000 men. Ras Makonnen had advanced ahead of the Emperor and was approaching Amba Alage in Tigrai itself. With the Ras and his Harrar troops were the Armies of Ras Mengesha Yohannis and Ras Welle Bitul. The three Rases agreed that an attack on the small fort on Amba Alage would not be worth the cost in men, as it was situated on a steep mountain top that favored the Italian defenders of the fort. They intended on marching past the fortress and proceeding on to Mekelle or Adigrat itself where the main body of the Italian forces was located. Others had different ideas however. Fitawrari Gebeyehu led a force of 1200 men and attacked a small unit of Italians who were on a scouting mission. The Italians retreated into the fortress and gunfire was exchanged. Ras Makonnen had been repeatedly sending messages asking for negotiations with the Italians, who kept putting him off so he had little intention of fighting here. Besides, Ras Mengesha, and Ras Welle, all advised bypassing Amba Alage for the more important town of Mekele. Besides, their forces were only the advance force, the main force was still 300 kilometers away. Now, December 7th, 1895, with the sound of gun fire soldiers began to leap up, grab their weapons and charge into battle. Fitawrari Gebeyehu had caused fighting to start where the princes definately did not want to start it. The Italians had the advantage of a stratiegic mountaintop fortress from where even a rock thrown down could do much damage. Inspite of repeated orders to hold back, neither the Tigreans of Ras Mengesha, nor the Amharas of Rases Welle or Mekonnen could be stopped. The situation was rapidly moving out of the hands of the Rases. The situation had deteriorated to the point where they had to throw everything into the assault. Major Toselli sent messages to General Arimondi at Mekelle (only 25 kilometers away) asking for re-inforcements as waves of Ethiopian warriors tried to clamber up the steep slopes of Amba Alage. Arimondi requested orders form General Baratieri at Adigrat and was told not to send any re-inforcements to Amba Alage. Instead he was told to instruct Toselli to hold the Ethiopians back for a while, then to withdraw in stages towards Mekelle slowly, in a delaying tactic. For some inexplicable reason, General Arimondi did not send these directions to Major Toselli who fought on at full force, expecting re-inforcements to be arriving at any time. The casualties were very steep on the Ethiopian side because of the advantage of position enjoyed by the Italians. However, after a battle that lasted six hours, only 400 of the 2000 members of the Italian army were able to escape with their lives, fleeing for Mekelle. Ras Sebhat, the Shum of Agame, already battling serious doubts in facing his countrymen on the side of forienors, fled with his soldiers, badly shaken. Sheik Tohla Ben Giafer also fled, and with him went any hope the Italians had of inciting the Muslims into rebellion. Major Toselli died in the battle, and the Ethiopian flag flew over Amba Alage. Chris Prouty writes that Queen Margarita of Italy wrote a friend "This death of Toselli is so sublime...that tears, not of grief but of admiration spring to the eyes..." The Italians had thier "Gordon", a brave stalwart white hero who had fallen in the service of his country in the heart of "Darkest Africa". The anti-colonial and republican elements in Italy demanded a withdrawal from Africa, but were drowned out by calls for vengance. For the Ethiopians the great man of the day was Fitawrari Gebeyehu. Emperor Menelik's chronicler writes that "Amharas and Tigreans shouted his name calling him 'Gobez-ayehu'." (This plays on his name changing it to mean "I have seen a brave man"). Ras Makonnen and Ras Mengesha were very angry however at the Fitawrari's autonomous action that had cost them many men. When he heard of the victory at Amba Alage, the Emperor was pleased, but was also aware that he had to punish Gebeyehu for begining the war without orders. He ordered Gebeyehu to be chained for three weeks as punishment. However, the Emperor at the same time didn't fail to chuckle and brag about his "brave Gebeyehu". The Emperor ordered that Major Toselli be given an honorable burial. This immediately caused angry protests on the part of the brothers of the Eritrean nobleman Bahta Hagos, who had led an anti-Italian uprising in 1894, and been defeated and killed by the Italians. On Major Toselli's personal orders, Bahta Hagos' body was refused burial despite the pleas of his family, and was left out in the open so that it could be eaten by hyenas. They demanded the right to exact vengance by leaving Toselli's corpse in the open as well, for the vultures and hyenas to feed on. Menelik is said to have told the family of Bahta Hagos not to sink to the "Un-Christian barbarity of the Italians", and ordered the funeral to be carried out. This comment must have galled the Italian officers in Mekelle and Adigrat to no end.

With the victory of Amba Alage, Menelik and the main force of the Ethiopian forces advanced into the heart of Tigrai. He passed through the Alamata Pass on December 14th and held a huge military review at Lake Ashenge. As he left Lake Ashenge, caution required the Emperor to steer clear of the camp of Ras Michael of Wollo because of an epidemic among the horses in that camp. To the shock of the Italians, on December 24th, King Tekle Haimanot of Gojjam arrived with his 5,000 troops and joined the army of the Emperor. The Italians had sent numerous gifts and much money to the King who had always been very friendly to them. Their spies had assured them that the Gojjame king had many grudges against the Emperor, and would never join him agianst the Italians staying neutral. He might even take the opportunity to reble they said. Besides, ever since the vicious campaign in Gojjam by Emperor Yohannis IV, just before Mettema, Tekle Haimanot was said to hate the Tigreans for the death and distruction they had sowed on his kingdom, and that he would, never come to fight for them. What the Italians failed to realise was that many of their native born spies were actually feeding them false information and were actually working for the Emperor. They also didn't know that when faced with an outsider enemy, even bandits and rebles would rally behind their monarch and their flag, let alone a good friend of Menelik and patriotic Ethiopian like Tekle Haimanot of Gojjam. The Italians were further frustrated to learn that a large army commanded by Ras Wolde Giorgis, Ras Tessema Nadew, and Azajh Wolde Tsadiq had surrounded Ausa, preventing the Sultan from taking any action to help them as he had assured them he would. Still however, the Italians were firm in their belief that their "superior civilization" would guarantee them victory over this rable. The thinking of the day was that there was no way a nation of blacks could outwit or outmanuver Europeans, and military the victory of a modern well armed European army in Africa was assured.

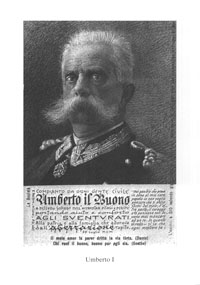

Umberto di Savoia, King of Italy

In Tigrai, the Emperor and Empress of Ethiopia, the King of Gojjam, the Rases and Dejazmatches, Fitawraris, Grazmatches and Kegnazmatches, Amhara, Tigrean Oromo and Gurage prepared to do battle not just militarily but spiritually as well. During their stay in Tigrai, the Emperor and Empress visited the Monastery of the Holy Trinity at Cheleqot, where the great Ras Welde Selassie. and Empress Tiruwork Wube (widow of Tewodros II and cousin of Empress Taitu) were buried. Emperor Menelik is said to have been deeply affected by this holy site, and is said to have pledged that if victory was his, he would give the monastery his gold encrusted robes of state. At the nearby Church of St. Mary, Empress Taitu is said to have sat vigil deep prayer for an extended time, praying for the intersession of the Mother of God for Ethiopia. She is said to have commented as she left "My Lady always answers me without delay." Because of this comment, this site is still refered to as "Airefedat Mariam".