THE LOESS PLATEAU:

PEOPLE OF THE DUST AND PRC POLICY

China’s Loess Plateau has the planet’s most extensive soil erosion, and China’s socio-economic and environmental issues will be of vital importance in the next century. The nature of loess and the Huang He must be understood to comprehend what China is facing. Achieving this research goal enables further investigation into the interlocking relationships of the Chinese government, the inhabitants of the loess region, and the World Bank. All are found to be participants in the search for policy solutions involving agriculture, industry, and genuine development of the Loess Region.

INTRODUCTION

As Modern China opens its doors further bit by bit to globalization and trade, issues of land use and economic development are brought even further to the forefront of this ancient culture’s slow rise to modernization. The PRC’s practical response to rising demands for agriculture and soil restoration coupled with a strong desire for freedom from abject poverty will aid in ascertaining how the country will fare in this new century.

China’s Loess Plateau is characterized by some of the most extensive soil erosion in the world, and around 40 million people make this area their home. The ecological devastation present in this region is influenced by a variety of factors that involve the inhabitants, their government, and the very nature of the soil that they live on.

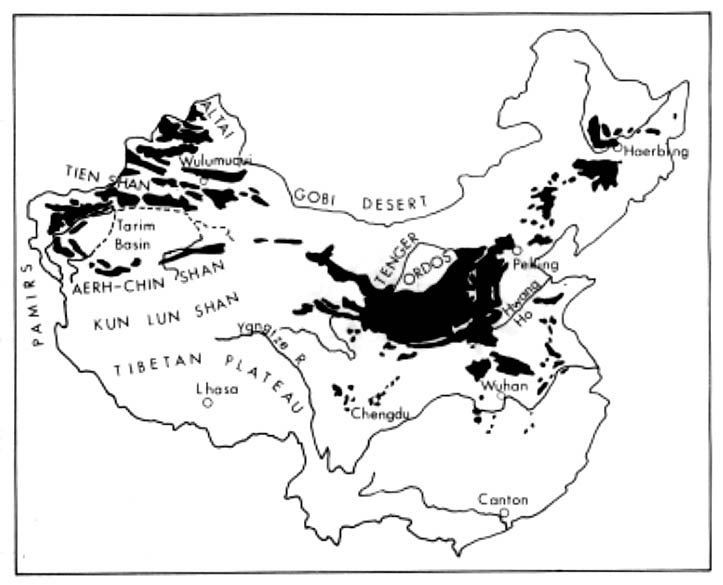

In order to gain a significant understanding of the issues that the Loess inhabitants face and the PRC’s responses to these issues, an exploration must be made into the specific uniqueness of the Loess Plateau’s environment. Researching into the nature and characteristics of loess soil is essential in this effort. This mass of dust covers most of Gansu, Shaanxi, Ningxia, Shanxi, and parts of Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, and Henan. This area is extensive enough to have inspired vigorous responses from the government in question, and an investigation must be made into the planning and guidelines through which such responses have been made.

The impact of weather patterns and the profound influence of the Huang He must also be examined, as patterns formed in this land help define the resource base for agriculture. It is only through understanding the problem can a solution can be found. In addition, revitalization of the Loess Plateau region cannot be explored as an option until issues such as chronic poverty and outward urban migration of the population are addressed. If sound policies for preserving the land can be discovered, then the people’s standard of living can be improved as well, while reserving a potential for the option of significant rural reform.

Fig.1. Provinces of the PRC Included in the Loess Region

Source: Perry-Castañeda 1

Origin and Formation of Loessal Soils

Understanding the conditions of the environment that people of the Loess Plateau inhabit is a necessity, and with this acknowledgement comes the need to establish what loess actually is. Containing more nutrients than sand, it is also much finer. Its silt-like nature is noted as being among the most erosion-prone soils known on the planet (Jiang 18). Loess is also extremely sensitive to the forces of wind and water, bearing the dubious honor of being blown or washed away quicker than any other soil type (Pye 125).

Prior to this century, loess was a compelling mystery for geologists seeking to know its origins. Former theories included that loessal deposits were beds of ancient oceans, and even that they were composed of cosmic Saturn-like rings of dust that may have once encircled the globe but somehow rained down in pockets (Pye 237). Into the 19th Century, however, an apparent agreement was shown between the timing of noticeable waves of loessal sedimentation and the glaciation of the northern hemisphere (Smalley 358).

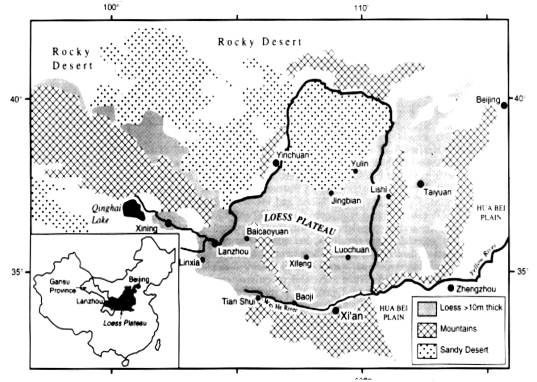

The Loess Plateau was formed in waves between 2.4 and 1.67 million years ago, helped along by the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, the movements of several huge glaciers across desert

regions, and strong winds maintained by a high-pressure system in a cold and dry continental interior (Meng and Derbyshire 141). It is the world’s largest deposit of loess, approximately the size of France, designated by the large black area in Figure 2 below (Yoong 95).

This mass of dust sprawls over the whole of Shanxi Province and great areas of Shaanxi, Ningxia, Gansu, and Henan Provinces (Yoong 95). Surrounded by the Ordos Desert to the north and mountain ranges in all other directions, it has a remarkable average thickness of 150 m, extending to 330 m near Lanzhou, as can be seen in Meng’s geomorphic regional chart (Figure 3) below.

Fig.2. Loess Distribution in China

Source: Smalley 360

Fig.2. Geomorphic Regions of the Loess Plateau

Source: Meng 140

Huang He’s Influence

Huang He, spelled “Hwang Ho” in Figure 1, girds the Loess Plateau and picks up the yellow dust that is its namesake; “Yellow River” is a literal translation. It reportedly receives, carries, and deposits downstream 30 times the sediment of the Nile River and 98 times the sediment of the Mississippi, with 90% of its sediment deriving from the Loess Plateau Region (Kleine 398). Annually, 1,600 million tons of loess is absorbed by the Huang He, causing the riverbed to rise by more than 10 centimeters every year and exceeding the land elevation on its banks by more than 10 meters in certain areas (Li 257). Nicknamed “China’s Sorrow,” this dust-swollen river is notorious for bursting out from its course and wandering over the nearby countryside, destroying crops and taking human lives (Smalley 362).

Any river’s natural flow, even when dealing with loess, is not solely responsible for such massive and unprecedented sediment load. Although the Plateau has rainfall that only amounts to an average of 20-55 centimeters (8-22 inches) a year, up to 40% of this annual precipitation has been known to fall in a single storm (Meng and Derbyshire 141). These violent rainstorms for the most part occur in the three months between July and September, contributing anywhere from 24-100% of the total annual sediment load into the Huang He (Luk 10). Gullies that are more than 40 km long after such storms rapidly appear in the Plateau, as the rainwater pushes easily through the fine dust and makes its way to tributaries of the river (Pye 136).

The Interaction of Climate and Erosion Patterns

As areas of the Plateau erode, a pattern of main morphological types tends to form. To begin with, there is the plateau itself, which is very flat and even table-like. Erosion sets in, and these flat areas are demarcated by sheer cliffs, becoming what is known by Chinese geologists as “yuan” (Pye 236). As the edges of the cliffs erode, vast ridges (or “liang”) are formed, which in turn erode into hemispherical hills known as “mao,” occurring with greatest frequency near the Plateau’s borders with the Huang He (Pye 236). These are the predominant, but not the exclusive, land patterns of the region; vast tunnels also form between layers of loess stratified by millennia of fluctuating sedimentary waves (Luk 18). Figures 4,5, and 6 below are typical examples of each of the three aforementioned morphological types:

Fig. 4. Yuan

Source: Yongyan and Zonghu 7

Fig. 5. Liang

Source: Yongyan and Zonghu 10

Fig. 6. Mao

Source: Yongyan and Zonghu 14

Anthropogenic Landscape: Its Legacy

China’s environment has been heavily influenced, and even shaped, by the Chinese people for at least 8,000 years, including 6,000 years of growing crops on the Loess Plateau (Kleine 398). This legacy, combined with overgrazing and a natural climatic trend towards aridity, has all but destroyed the natural vegetation cover of the Plateau (Cook, Li, and Wei 112). Cultivated land, loosened by tilling and lacking the protection of a dry cracking effect that naturally takes place in loessal regions, is 23% less resistant to erosion than uncultivated land (Luk 13). For a climographic analysis of temperature and rainfall in the region, see Figure 7 below.

Of all the factors contributing to soil erosion in the Loess Plateau Region, including desertification, wind erosion, violent rainstorms, and earthquakes, the most significant overall has been irrational land use (Bojie et al. 732). Slopeland, although much less stable than the level “yuan” tables (See Fig. 4), is continuously cultivated out of sheer need for increasing amounts of agriculture. These plowed slopes account for as much as 70% of soil loss in the region (Luk 23). However, it is not enough to simply declare the Loess Plateau inhabitants irrational. Many factors contribute to their use of the land in such a way.

LOESS INHABITANTS

The Cradle Of Chinese Civilization

Xi’an, located in the southern part of the Loess Plateau, is the ancient capital of Imperial China and is acknowledged as the source or cradle of the Chinese nation (Qinye, Liu, and Li 36). Archeological data has shown that cave dwellers lived in the region in prehistoric times, and recorded dynastic history is replete with references and descriptions of the region going back as far as 2,500 years (Li 257). In addition, evidence has shown that agricultural terracing in the region to improve water retention and lessen soil loss has been continually practiced for at least 3,000 years (Kleine 398).

Within China’s dynastic history can be found over 2,000 years of traditional neglect and abuse of the land in the Loess Region. From the Han (221 BC- 206 AD), when vast expanses of timber were harvested, to the Ming (1368 AD- 1644 AD), when vast “scorched-earth” fires were set to isolate and distance Mongol invaders, severe damage to the environment of the Plateau has been both chronic and common (Veeck, Li, and Gao 453).

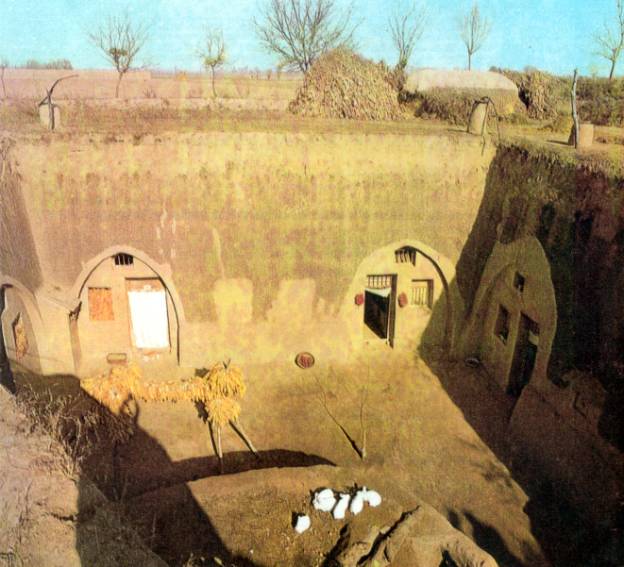

Agricultural Patterns

The Plateau’s inhabitants, faced with harsh and infrequent rainstorms and a homeland that has been deforested for over two millennia, also suffer from some of the worst abject poverty in all of China (Li 258). Traditional agricultural techniques continue as land productivity stagnates under the weight of massive soil erosion (Luk 3). Of the estimated 70 million people who live on the Loess Plateau, up to 40 million still inhabit caves (Yoong 95). The traditional crops are potatoes, beans, maize, and millet, all grown predominately on the steep slopes of “mao” loess formations (Bojie et al.736).

As if patterns of drought and chronic erosion don’t suffice for natural hazards and hardships, the region is also prone to both landslides and earthquakes. The Haiyuan earthquake of 1920 alone killed 230,000 people, caused 650 loess collapses, and formed 41 dammed lakes (Pye 237). Landslides, mostly caused by tremors and earthquakes, have taken several hundred thousand lives in the last 100 years in at least 40,000 separate locations on the Plateau (Meng and Derbyshire 141).

The ancient art of terracing has been a mainstay of subsistence agriculture in the region. Although known to contribute as much as 70% to the overall sediment load of the Huang He, this cultivated slopeland is common and widespread (Luk 23). Often the terraces are topped with small trees or bushes to impede the process of erosion. Figure 8 below shows a standard manmade terrace in Shaanxi Province:

Fig. 8. Terraced Plot on the Loess Plateau

Source: Yongyan and Zonghu 56

Crop yields of the Loess Plateau are limited not only by infrequent and violent rainfall, but also the substantial temperature variations of continental climates; long and freezing winters of minus 30º C are matched by summer temperatures that soar sometimes above 30º C (Yoong 100), as can be seen in Figure 7. Inhabitants cope with this huge seasonal temperature variation by relying on geomantic principles set forth in the ancient Chinese practice of Feng Shui, such as building a home that backs into a hill and faces south, keeping the most constant indoor temperature possible (Yoong 97). An example of this sort of traditional adaptation can be seen in Figure 9 below:

Fig. 9. Cave Dwellings in the Loess Plateau Region

Source: Yongyan and Zonghu 33

Although the use of natural resources through homebuilding and agriculture has been relatively unchanged in the long history of settlement on the Loess Plateau, the population’s rapid growth is a very modern problem (Li 258). Famine and poverty actually give rise to this growing population in the region, as more and more labor is needed to cultivate more and more virgin land. It is interesting to note that when such population pressure is removed, as in localized cases of famine or plague, vegetation regrew naturally and soil erosion almost totally ceased (Luk 26).

Government help from the Party leaders of the People’s Republic of China has been mixed. Before the 1949 Communist Revolution, the frequent droughts in the Loess Plateau often led to famine, with the modern government sometimes resorting to shipping in grain and water by truck (Cook, Li, and Wei 112). Since the Revolution, many agricultural and rural reforms took place in the form of constant waves of Five-Year Plans.

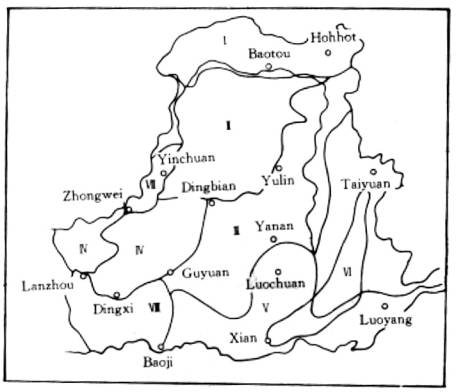

A series of such plans entitled the “Loess Plateau Integrated Research Programme” sought not only to study causes and impacts of erosion and deforestation, but to look at what constructive steps could be taken (Jiang 105). The rather bleak findings of the Seventh Plan in this series (1986-1990) are provided by a trio of contributing Chinese geologists in Figure 10:

|

ReGIONS |

Environmental Problems |

|

I. |

Pollutions, soil salinization, wind erosion, desertification, water and soil loss, drought, rainstorm. |

|

II. |

Endemic diseases, wind erosion, desertification, water and soil loss, drought, rainstorm. |

|

III. |

Pollutions, endemic diseases, drought, water and soil loss. |

|

IV. |

Pollutions, water and soil loss, drought, geological disasters. |

|

V. |

Endemic diseases, pollutions, forest over-cutting, water and soil loss, drought, rainstorm. |

|

VI. |

Pollutions, drought, soil salinization, earthquakes. |

|

VII. |

Earthquakes, pollutions, soil salinization. |

|

VIII. |

Landslide, endemic diseases, rainstorm, water and soil loss. |

Fig. 10. Leading Environmental Problems in the Loess Region

Sources: Qinye, Liu, and Li 43

Although the above study was comprehensive enough, constructive steps beyond mere consultation did not really take place. The most effective program to date that involved both the Chinese government and the Loess Plateau is the Qinba Mountains Poverty Reduction Project, which began in early 1997 in 26 poor counties that included the Loess Plateau areas of Shaanxi and Ningxia Provinces (see Figure 1) (Piazza and Liang 263). This program, sponsored in part by the World Bank, has proven so effective in the multisectoral areas of microfinance, public health care, education, and rural infrastructure, that it has been nationally extended to all of the 592 nationally designated poor counties (Piazza and Liang 263).

One of the most noticeable findings in the Integrated Research Programme study explored in Figure 4 was that of a problem with endemic diseases in the Loess Plateau area. These are mostly due to the industrial pollution stemming from the concentrated use and extraction of the rich coal resources found there (Qinye, Liu, and Li 39). Five major industries, electricity, petroleum, petrochemicals, metallurgy, and engineering, are all concentrated in the urban area around Lanzhou Municipality in Gansu Province (Jun 94). Nearby Shanxi Province is described as “a sulphurous province of coal mines” (Economist 45).

Resulting from this process of industrialization is not only disease, but a pattern of polarization around areas of industry, leading to serious overcrowding and job-seeking in a population that on average barely makes the equivalent of $50 a year (Economist 46). Gansu Province, the home of Lanzhou’s concentrated industrial polarization, has a startling illiteracy rate of 48%, in which less than one percent of the population has a college education or its equivalent (Jun 99). These factors of stunted economy and barren education tend to perpetuate each other, and the pursuit of modern industry has done nothing to rectify this dilemma.

Beginning with the so-called Steel Melting Movement of 1958, which involved the vast over-harvesting of rural forests, and leading up to the prioritization of industry over natural environment, modern China has had a somewhat spurious record of impact on its rural regions, the Loess Plateau being no exception (Li 258). Although 1990-1995 has seen the rise of a Chinese middle class concentrated in the coastal provinces, incomes in many rural areas have declined as production costs rise and prices for output have stagnated (Veeck, Li, and Gao 452).

It has been argued that the very fundamental economic doctrines of Marxism include detrimental effects such as weakening of worker responsibility and runaway inflation, while aspects such as an absence of private ownership and a lack of the market price mechanism also further detract potential for productivity and economic efficiency (Li 254). Meanwhile, on the Plateau, promised reservoirs and irrigation systems seem to be perpetually postponed, and for two of the years between 1990 and 1995, farmers have not even received cash payments for the food they sold to the State (Veeck, Li, and Gao 452).

The government has sponsored extensive reforestation projects that continuously fail due to both internal corruption and the unwillingness of local rural populations to devote land, so that the deforestation rate remains one and a half times faster than that of reforestation (Li 258). While the post-Mao reforms continue to change the face of China, aspects of the system that hinder positive economic or environmental progress are still to some extent in place.

During the 1980’s, including the Five-Year Loess Plateau Integrated Research Programme whose findings are shown in Figure 10, considerable research has been conducted on soil erosion and land management in the Loess Plateau region (Luk 3). While most reforestation techniques have fallen short of providing local populations with suitable alternatives, several demonstration projects have proved beneficial (Kleine 399).

One of the most remarkably successful of these has been a proposal conducted by agricultural scientists out of Gansu Province known as “Rainwater Harvesting Agriculture” (Cook, Li, and Wei 113). The idea involves widened terraces, plastic soil covers to reduce evaporation rates, extensive check dams, and concrete and plastic catchments to reduce sediment load in the water (Cook, Li, and Wei 113). This plan infuses sound environmental policy with a dedication to benefit local populations, and shows great potential if further implemented by the state.

Other proposals involving concentration of crops on flat tableland as opposed to terraces as well as planting fruit trees in the massive loessal gullies have shown to triple agricultural output while reducing soil erosion by as much as 70% (Kleine 399). By such methods, 150,000 hectares (370,000 acres) of plateau have been rehabilitated in the years between 1994 and 1998 (Economist 46). A slogan was spotted in huge characters in 1998 on a renovated hillside in the Plateau region: “Master the mountains and conserve the waters; Change heaven and revive the earth” (Economist 46).

Basic objectives of this research have been to explore not only the conditions of the inhabitants of the Loess Plateau, but also the role that the modern Chinese government plays in their lives. Serving as a true environmental test for the Communist government, the unique environment of the Plateau itself helps define the agricultural methods used. Therefore, an analysis of geological origins and perspectives must in turn be followed by a long look at China’s reaction.

A definition and exploration into the possible origins of loessal soil in general brought into focus the significance of the Loess Plateau. In addition, the Huang He’s influence on the region in terms of environmental impact, sedimentary load, and influence on policy were shown to contribute to the overall picture of the Plateau. Geomorphic formations due to wind and soil erosion were investigated, and the historical legacy of Chinese impact on the Loess Plateau’s environment was also shown as vital in understanding the region as it stands now.

Unique agricultural patterns of the Loess Plateau farmers, including their cave dwellings, add to both the region’s uniqueness and the people’s gift of adaptation. Regrettably, conflict was shown between these ancient traditions and environmental preservation. Not only does the traditional agriculture contribute to further soil erosion, it also serves as a gulf between the people and their government.

The PRC’s role in resource management and rural reform were both shown to have promise, but also to be lacking. This is partially due to the nature of Marxism itself, but many societal and economic factors contribute. Promise remains in both anti-poverty campaigns and rainfall harvesting projects.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this research show that in order for significant improvement of the standard of living for the inhabitants of the Loess Plateau to take place, a shift in priorities must take place within the Chinese government. Over-industrialization has shown the Chinese, even through their own funded research, that it can lead to diseases, a depletion of human resources, and an extensively negative effect on the physical environment. In addition, some reforms should be modified, while others should be explored further. The needs of the cities downstream cannot be placed above the needs of the rural population, otherwise true unity of the country and the culture will not be achieved.

Problems in attaining research objectives included long waits for vital texts acquired through a slow Interlibrary Loan process. Although resources at the University library did exist, the majority of the recent and vital work had to be ordered from elsewhere. Also, much of the research done in this area has not yet been translated into English. A researcher who can read Chinese fluently would be able to explore the issue of the Loess Plateau in modern China more thoroughly.

Despite the wait, however, research was conducted with many sources, and very recent translations were provided by the course instructor. The final result was a close look at the Loess Plateau that involved a healthy variety of perspectives, both Chinese and non-Chinese.

WORKS CITED

“Asia: Precipitation Problems.” The Economist 26 Sept. 1998: 45-46.

Bojie, Fu, Ma Keming, Zhou Huafeng, and Chen Liding. “The Effect of Land Use Structure on the Distribution of Soil Nutrients in the Hilly Area of the Loess Plateau, China.” Chinese Science Bulletin 44 (1999): 732-737.

Cook, Seth, Li Fengrui, and Wei Huilan. “Rainwater Harvesting Agriculture in Gansu Province, PRC.” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 55 (2000): 112-114.

Gibaldi, Joseph. MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing. 2nd ed. New York: MLA, 1998.

Jiang, Hong. The Ordos Plateau of China: An Endangered Environment. New York: United Nations UP, 1999.

Jun, Li. “Application of the Growth-Pole Theory to the Economic Development of the Loess Plateau.” Trans. Hu Wei. Chinese Geography and Environment: A Journal of Translations 2.4 (1989-90): 92-100.

Kleine, Doug. “Who Will Feed China?” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 52 (1997): 398-399.

Li, Jingneng. “Comment: Population Effects on Deforestation and Soil Erosion in China.” Population and Development Review 16 (1990): 254-258.

Luk, Shiuhung. “Soil Erosion and Land Management in the Loess Plateau Region, North China.” Chinese Geography and Environment: A Journal of Translations 3.4 (1990-91): 3-28.

Meng, Xin-min and Edward Derbyshire. “Landslides and Their Control in the Chinese Loess Plateau: Models and Case Studies From Gansu Province, China.” Geohazards in Engineering Geology 15.1 (1998): 141-153.

Piazza, Alan, and Echo H. Liang. “Reducing Absolute Poverty in China: Current Status and Issues.” Journal of International Affairs 52 (1998): 253-65.

Pye, Kenneth. Aeolian Dust and Dust Deposits. Orlando: Academic P, 1987.

Qinye, Yang, Liu Xuehua and Li Guodong. “Critical Environmental Situation in the Middle Reaches of the Yellow River in China.” The Journal of Chinese Geography 6.1 (1996): 36-47.

Smalley, Ian J., ed. Loess: Lithology and Genesis. Stroudsburg: Dowden, 1975.

Veeck, Gregory, Li Zhou, and Gao Ling. “Terrace Construction and Productivity on Loessal Soils in Zhongyang County, Shanxi Province, PRC.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 85 (1995): 450-67.

Yongyan, Wang, and Zhang Zonghu, eds. Loess in China. Xian: Shaanxi People’s Art Publishing House, 1980.

Yoong, Hong-key. “Loess Cave Dwellings in Shaanxi Province, China.” Geojournal 21 (1990): 95-102.

![]()

SHORTCUT MENU:

Diary: Index: Writings: Inner Pages: Research:Teachings: