Organic by Design: This particular version of the organic architecture concept traces its formal roots to the 19th century, a time of rampant scientific exploration and discovery and rapid fortuitous invention. We tend to regard that time as a period when western man engaged in earnest that long standing war between nature and technology which has today left us trapped in a cold, polluted, and increasingly artificial world. But the 19th century was also a time when mankind started examining nature with an almost obsessive intensity, seeking through both science, art, and philosphy to understand its 'machinations' at the deepest level. And so it is no surprise that during this period a style of art, design, and architectural expression should arise which was founded on the man-made emulation of natural, organic, forms. A style known as Art Nouveau.

The Art Nouveau movement is said to have begun in France and Belgium in the later part of the 19th century. In fact, the term "Art Nouveau" was taken from the name of a Paris shop, operated by a german merchant, which first began selling art, furniture, and craft items designed with this new aesthetic. But the real origin of Art Nouveau architecture may in fact be found in England and the grand works of Joseph Paxton.

Paxton was born in 1803 and at the age of 23 was hired by the Duke of Devonshire to be the head gardener for Chatsworth gardens. There he built a very beautiful greenhouse structure called the lily house, its ironwork structure based on the structures he observed in the living lily plant itself. So impressed with his results, Paxton decided to employ the same structure in a proposal for the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park. The result was the legendary Crystal Palace, one of the most beautiful architectural works in history, and the first of what we today refer to as 'high performance structures'. [picture: Crystal Palace] We see much of Paxton's original insight emerge later in Art Nouveau, particularly in the choice of its two most characteristic materials; iron and glass.

The Art Nouveau movement was based primarily on the concept of reproducing natural organic forms either literally, by stylistiically simulating the appearance of plants and animals, or figuratively, by emulating the curves and textures of natural structures and materials. Art Nouveau is often considered a 'romantic' form of architecture, cheifly because it seeks to create the impresison of an idealized and magical world where human artifice and natural creation become indestinguishable. Indeed, elements of Grecco-Roman mythology and Medieval fantasy were frequently employed. Though the forms of plants seemed to provide the primariy inspiration for Art Nouveau designers, there is certainly no shortage of prancing fauns, fairies, dragons, and mermaids inhabiting the fluid glass and ironwork. One should bear in mind that this was quite in keeping with the spirit of the times. Though marked by the apparent obsession with industry and imperialism, the 19th century actually saw a romantic and esoteric renaissance. Spiritualism was the predominant religion in America for much of the century and Europe saw not only the rise of Spiritualism but also neo-paganism and a host of mystical 'sciences'. Fantasy literature was in abundance and classical, ancient Egyptian, and Celtic mythology were much in vogue as themes in fasion, design, art, and architecture. But beyond the ornamentation, there was an organic sensibility, an attempt to find a continuity between the natural and artificial, dirived from the duplication of the essential structural systems formal science discovered in the forms and structures of plants and animals and which, it's no surprise, has it counterpart in Primary Architecture. So, once again, we come back to that humble dung hut whose spiral shape is duplicated by any number of different plants and animals, and any number of different Art Nouveau works.

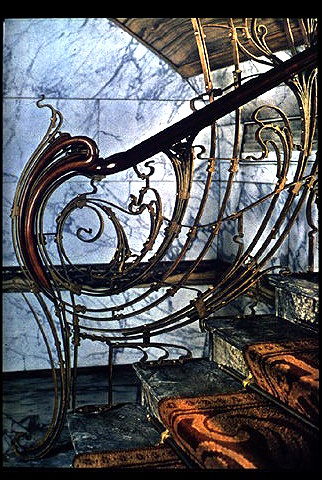

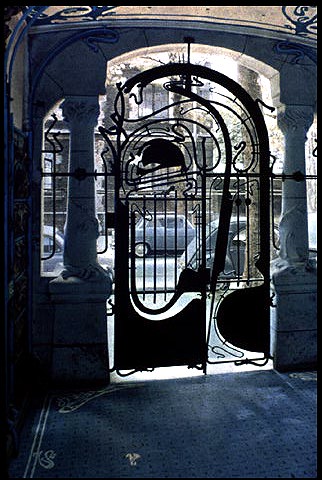

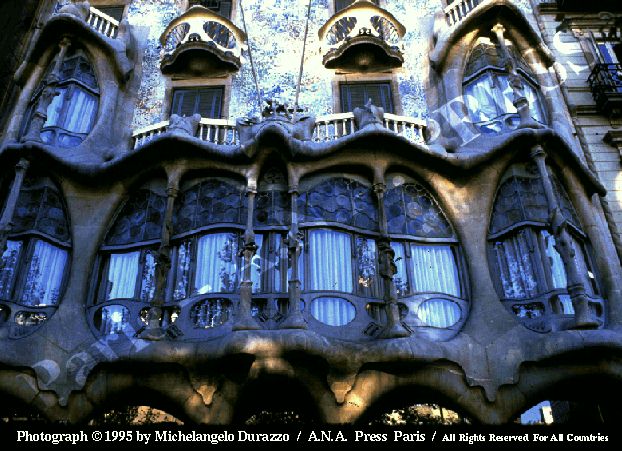

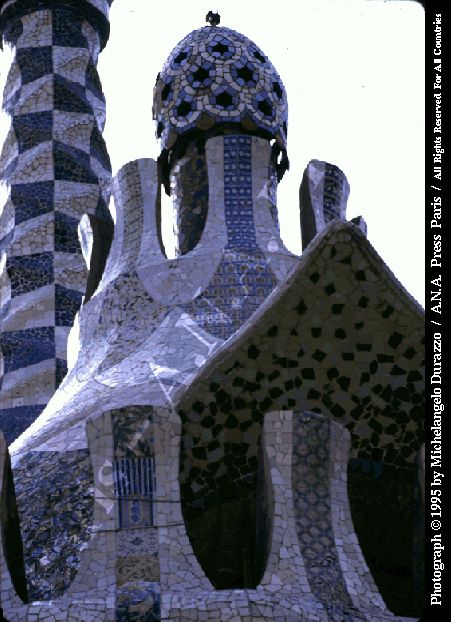

Three architects most typify the Art Nouveau movement in architecture; Hecter Guimard, Baron Victor Horta, and Antonio Gaudi. All employed organic forms as both ornamentation and as essential structural elements. Of the three, Gaudi may have had the most influence upon the contemporary form of architecture often referred to as 'free form' organic architecture, this because he made such extensive use of the then rarely used reinforced concrete.

[stairs Hotel Solvay, Brussels - Horta]

[entrance Castel Beranger, Paris - Guimard]

[Metro Dauphine, Paris- Guimard]

[Casa Mila, Barcelona - Gaudi]

[building facade - Gaudi]

[domes - Gaudi]

[waiting room of Battle House, Barcelona - Gaudi]

An Expresionist artists and architectural visionary named Hermann Finsterlin seems to have anticipated the free-form organic architecture of modern times as early as 1919. Though his designs never resulted in actual buildings, they show an almost prophetic insight. (note the incredible similarities between these drawings and the 1970s-80s works of Roger Dean shown later)

[pictures of Finsterlin designs]

Another early experimenter with the organic design concept was artist, architect, and philospher Rudolf Steiner who founded a school of 'anthroposophy' for which he built a most unusual building called the Goetheanum, named for the German philospher and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The unusual building was designed to suggest forms of human organs and was actually built twice, the first version, built in 1913, having been destroyed by fire in 1922 and the second, completed in 1929, standing to this day. The second version is in fact closer to current conceptions of organic design and, though less lavish, is by far the more elegant version. Here we see the beginning of an evolution from Art Nouveau, which by this time was on its last legs as an art and cultural movement, to Modernism.

[original Goetheanum - Steiner]

[Goetheanum today]

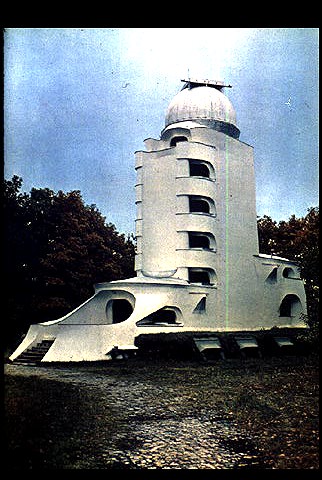

Another singular but much more famous experiment from this same era is the renown Einstein Tower in Potsdam; an astronomical observatory and science building of the Astro-Physicial Institute of Postadam designed by the German-American architect Eric Mendelson. Built in 1921, this unique and futuristic building was planned for construction in concrete, which was very rare for the time, but was ultimately executed in brick with a stucco finish. This is most clearly a Modernist work but is quite atypical of the Bauhaus inspired concepts of Modernism then beginning to dominate the leading edge of architecture. The organic influence of Art Nouveau and of Gaudi is still clearly in evidence here but with the flowing forms more abstracted and made symmetrical, orderly.

[picture Einstein Tower, Potsdam - Mendelson]

In these last examples we can see an evolution of the organic design concept away from the stylistic nature-mimmicry of Art Nouveau toward an increasing abstraction which was to find its conclusion in the purely abstract organic modernist designs of works such as Le Corbusier's controversial Chapel Notre Dame du Haut, built in the early 1950s. Here the flowing organic forms are minimized to the point where any resemblance to forms in nature is virtually gone and instead we have architecture as purely abstract sculpture.

[Chapel Notre Dame du Haut, France - Le Corbusier]