|

|

Left: An artistic portrayal of a toast. Hip hip horray! Artists celebrating at Skagen by Danish painter P. S. Kroyer, 1888. Gothenburg Museum of Art. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

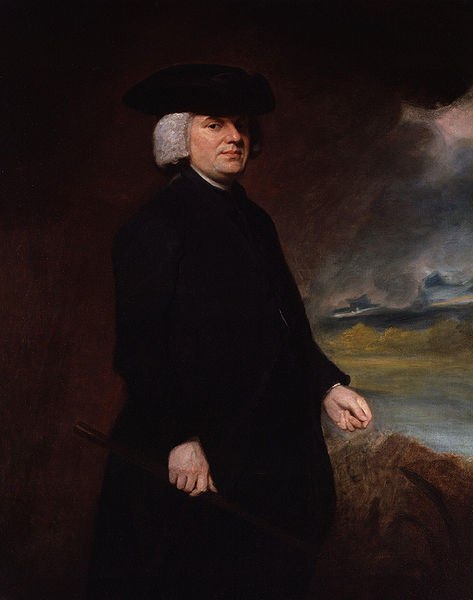

Right: Rev. William Paley (1743-1805), a man to whom I'd like to offer a posthumous toast. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Thomism and Intelligent Design: MAIN PAGE Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 (current page) Page 5 Page 6 Page 7

Ladies and gentlemen, please be upstanding. I'd like to propose a toast to Rev. William Paley (1743-1805), a brilliantly lucid expositor of the Argument from Design and a man of courage, integrity and humanity.

In this post, I'm going to talk about Paley's famous (and much-misunderstood) Argument from Design. Despite the limpid clarity of Paley's prose in his Natural Theology, it is frequently misconstrued. In Section 2, I'll be puncturing twelve commonly accepted myths about Paley's design argument. In Sections 3 and 4, I'll be discussing what two Thomist professors have to say about Paley's argument from design.

Professor Edward Feser thinks Paley's argument from design actually takes us to a false god - a Demiurge, rather than a Deity - despite the fact that Paley himself argues for the existence of a transcendent Being, beyond space and time, Who maintains every creature in existence and Who is infinite in Wisdom, Power and Goodness. Feser also mistakenly thinks that Paley's argument is a merely probabilistic one, when in fact Paley declares over and over again that he intended it as a proof. I regret to say that Professor Feser has completely misread Paley's Natural Theology - which is quite an astonishing feat, as it is written in the clearest and most elegant language one could possibly hope for, in an argument for the existence of God. I'll be responding to Feser's criticisms in Section 3.

Professor Marie George, who is well-versed in the writings of Rev. William Paley, takes a much more synpathetic view of the man than Feser does. In a recent article entitled, "An Aristotelian-Thomist responds to Edward Feser's 'Teleology'", (Philosophia Christi, Vol. 12, No. 2, Spring 2010), she argues that Paley's and Aquinas' arguments are much closer than is commonly supposed. I'll be commenting on her claims in Section 4.

In Section 5, I shall address a question of historical interest: if the philosopher Paley wasn't a mechanist (as is commonly alleged), then who was? Which philosophers embraced this error? The answer, as it turns out, is that it was the philosophers of the seventeenth century who were the most enthusiastic proponents of mechanism - especially Descartes and Boyle.

But before I discuss Paley's Argument from Design and evaluate what Professors Feser and George have written about Paley, I'd like to say a little about the man himself.

|

|

Left: Rock Pigeons feeding in the park of Schonbrunn Palace, Vienna. Image courtesy of Alexander Gamauf and Wikipedia.

Right: King George III, the monarch who excluded Rev. William Paley from the highest positions in the Church of England because of his progressive political views. Portrait by Allan Ramsay, 1762. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

William Paley is famous for his Parable of the Pigeons, criticizing the monopolization of power by kings. In the parable, Paley likened the human race to a flock of pigeons, gathering all the food they could collect into a heap without reserving anything for themselves, and being forced to give it all to one greedy pigeon in the flock. King George III blocked Paley's promotion because he found the parable so offensive.

William Paley (1743-1805) was an English Christian apologist, theologian and philosopher who is best known today for his 1802 work, Natural Theology: or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature, in which he put forward a teleological argument for the existence of God. Other popular works of Paley's include his The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785) and his A View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794). After graduating from Christ's College, University of Cambridge, in 1763, Paley was elected a fellow of the College in 1766 and became a tutor there in 1768, teaching moral philosophy, divinity and the Greek New Testament. In 1767, Paley was ordained an Anglican priest, and in later life, he served numerous parishes, becoming Archdeacon of Carlisle in 1782 and subdean of Lincoln Cathedral in 1795.

There's a lot to like about William Paley. American readers will like him, since he enthusiastically supported the American colonies during their War of Independence.

Civil rights advocates will like him too, as he was a tireless campaigner against the evil of slavery.

People who oppose religious bigotry should admire Paley, as well. In his classic work, Natural Theology (1802), he expressed the hope that "That part of mankind which never heard of Christ's name, may nevertheless be redeemed, that is, be placed in a better condition, with respect to their future state, by his intervention" (Chapter XXVI, p. 530).

Paley's political views: progressive but not radical

The following extract from Paley's Wikipedia biography conveys his political views, which were strikingly progressive for his day:

Paley strenuously supported the abolition of the slave trade, and his attack on slavery in the book was instrumental in drawing greater public attention to the evil trade. In 1789 a speech he gave on the subject in Carlisle was published.Some of his other political, social and economic ideas are remarkably advanced. He defends the right of the poor to steal, particularly if they are in need of food, and proposes a graduated income tax in order to limit excessive accumulations of wealth in few hands. He was also an advocate of enabling women to take up careers, rather than perpetually to depend on the property owned and inherited by male relations. (He was well aware of the fact that women lower in the social scale worked - his argument was with the system which prevented talented and capable middle-class women from taking a role in the economy.)

Paley's famous, and controversial, fable of the pigeons, which has a strong criticism of the system of property ownership and of the draconian means used to defend it - the Bloody Code - is found in Book III of [Paley's 1785 work,] Principles [of Moral and Political Philosophy]. John Law tried to get Paley to remove the passage, because it would prevent him becoming a bishop. Paley refused.

His political views are said to have debarred him from the highest positions in the Church, the King, George III, at one point saying, Pigeon Paley? Not sound, not sound. Even so, he was offered the Mastership of Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1789, by the Bishop of Ely, but he turned it down, being content with his life in Carlisle, and not wishing to disrupt his children's education. John Law observed at this time that "Paley has missed a mitre".

Readers might be curious to learn more about Paley's fable of the pigeons, so I've decided to reproduce it in full:

Paley's fable of the pigeons

"If you should see a flock of pigeons in a field of corn; and if (instead of each picking where and what it liked, taking just as much as it wanted, and no more) you should see ninety-nine of them gathering all they got, into a heap; reserving nothing for themselves, but the chaff and the refuse; keeping this heap for one, and that the weakest, perhaps worst, pigeon of the flock; sitting round, and looking on, all the winter, whilst this one was devouring, throwing about, and wasting it; and if a pigeon more hardy or hungry than the rest, touched a grain of the hoard, all the others instantly flying upon it, and tearing it to pieces; if you should see this, you would see nothing more than what is every day practised and established among men. Among men, you see the ninety-and-nine toiling and scraping together a heap of superfluities for one (and this one too, oftentimes the feeblest and worst of the whole set, a child, a woman, a madman, or a fool); getting nothing for themselves all the while, but a little of the coarsest of the provision, which their own industry produces; looking quietly on, while they see the fruits of all their labour spent or spoiled; and if one of the number take or touch a particle of the hoard, the others joining against him, and hanging him for the theft."

|

No doubt about it, the man certainly had a way with words.

I should point out that Paley was a staunch supporter of property rights, which he argued for very cogently in Book III, Chapter 2 of The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785). Paley was certainly no political radical: he did not support the French Revolution, and in his work, Reasons for Contentment: Addressed to the labouring part of the British public (F. Jollie, 1792), he urged workers to be satisfied with their lot in life, on the grounds that a life of labor "is attended with greater alacrity of spirits, a more constant chearfulness and serenity of temper" than the lifestyle of the rich.

Paley's belief that the poor have the right to steal from the rich in times of urgent necessity did not make him into a nineteenth century Robin Hood. What he actually wrote in Book II, Chapter 11 of The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy was that in a situation of "extreme necessity," each of us has "a right to take, without or against the owner's leave, the first food, clothes, or shelter, we meet with, when we are in danger of perishing through want of them." Such a statement can be paralleled by the declaration of St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica II-II q. 66 art. 7 (ad. 2, ad. 3), that "It is not theft, properly speaking, to take secretly and use another's property in a case of extreme need: because that which he takes for the support of his life becomes his own property by reason of that need," and "In a case of a like need a man may also take secretly another's property in order to succor his neighbor in need." (See here for a long list of Catholic theologians from the fourth century onward, who thought likewise.)

Paley's support of a graduated income tax was hardly radical either. If one examines his discussion of taxation in Book VI, Chapter 11 of The Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy it turns out that he was considering the effects of a 10% tax, levied upon the wealthy, who could afford to pay it much more easily than people of other classes. Readers who are well-versed in history will of course be aware that tax rates in Paley's day were much lower than they are now. According to Brian Roach's well-researched History of taxation in the United States, even during the American Civil War, "income tax rates were low by modern standards – a maximum rate of 10% along with generous exemptions meant that only about 10% of households were subject to any income tax." Indeed, as late as 1915, the top marginal tax rate was only 7%. It was only during the Woodrow Wilson administration that marginal tax rates skyrocketed to 73%, according to economist Thomas Sowell.

Paley's design argument: how well has it withstood the test of time?

|

|

Left: An eighteenth century portrait of David Hume. Scottish National Gallery. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

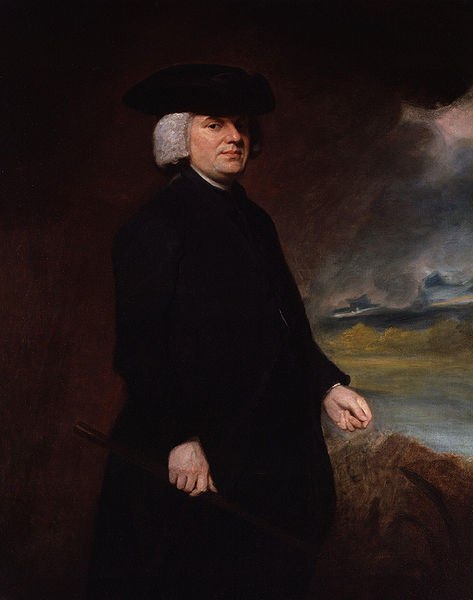

Right: Portrait of Charles Darwin, by George Richmond. Late 1830s. Image courtesy of Richard Leakey, Roger Lewin and Wikipedia.

Hume and Darwin are both popularly supposed to have refuted Paley's arguments. I argue below that this supposition is mistaken.

I wasn't always a William Paley fan, and I've only recently read his Natural Theology myself. Having read it, I have to say that I was profoundly impressed by the clarity of Paley's style and the cleverness of his argument.

Neo-Darwinists often claim that Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species, published in 1859, decisively refuted Paley's argument for a Designer, once and for all. For my part, I think Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection made a relatively minor dent in Paley's case. In a nutshell, Paley's argument is that intelligent agency is the only process adequate to account for the origin of what he calls contrivances - that is, systems whose parts are intricately arranged and co-ordinated to subserve some common end. (For the purposes of Paley's argument, it is utterly irrelevant whether this end is intrinsic to the parts in question, as in a living organism, or extrinsic, as in an artifact.) What Charles Darwin did was to put forward a mechanism (natural selection) which is capable (in principle) of explaining how one complex, highly co-ordinated system of parts which assists an organism's survival could, over millions of years, gradually evolve into another complex system serving an altogether different purpose, through an undirected ("blind") process. (Of course, such an evolutionary transformation can only occur if there is a viable pathway between the two systems, which blind processes are capable of traversing without any intelligent guidance.) What Darwin did not show, however, is how the fundamental biochemical systems upon which all organisms rely for their survival, could have came into existence, in the first place. We might refer to these fundamental systems in Nature as Paley's original contrivances. These contrivances cannot be explained away as modifications of pre-existing biological systems, since by definition, anything that preceded them was not viable. Some Neo-Darwinists have hypothesized that autocatalytic reactions, by creating more and more complex arrangements of parts, could have given rise to these original contrivances over millions of years. But this proposal ignores the most fundamental characteristic of living things: their teleology. How did these arrangements of parts come to serve a common end? A telos is not the sort of thing that comes in halves; a biochemical system either has it or it doesn't. I conclude that Paley's argument from design remains essentially intact. The origin of teleological systems without a Designer remains as inexplicable as it was in Paley's day.

Evolutionists still have one ace up their sleeve, however: the Scottish empiricist philosopher David Hume is widely supposed to have refuted Paley's argument from design on philosophical grounds. The supposition is absurdly anachronistic: Hume died in 1776, and his posthumous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion were published in 1779, but Paley's Natural Theology was not published until 1802. Paley had read Hume's Dialogues; indeed, he even refers in passing to "Mr. Hume, in his posthumous dialogues" on page 512 of Chapter XXVI of his Natural Theology. Moreover, a careful examination of Paley's design argument shows that he had anticipated and responded to Hume's main criticisms. For the purposes of this post, I'd just like to draw attention to one major difference between the design argument put forward by the character Cleanthes (and subsequently refuted by Philo) in Hume's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, and the design argument formulated by Paley. As Professor John Wright has pointed out in some online remarks on Hume's Dialogues, Cleanthes' design argument was an inductive argument based on an analogy between human artifacts (which we observe being produced by intelligent agents) and the machines we find in Nature, whereas Paley argued that we could immediately infer Intelligent Design from any machine we happen to find:

Paley thinks we infer the existence of an intelligent cause immediately from the observation of the machine itself. According to the argument which Cleanthes puts forward, the only reason we ascribe an intelligent cause to machines like watches, is because we discover from observation that they are created by beings with thought, wisdom and intelligence. (Paley had read Hume and was obviously aware of this difference in their arguments: see his answer to his first Objection.)For Paley the inference from watch to intelligent watchmaker is no different from the inference from complex natural organisms to an intelligent designer. He is just trying to show you can make the same inference in both cases. For Cleanthes, on the other hand, it is important that we observe the maker in the case of the human productions and we do not in the case of the productions of nature. We observe the effects in both cases and that they are somewhat similar to each other. But we never observe the cause in the case of natural machines: it is only inferred through the scientific principle "like effects, like causes." Cleanthes draws the conclusion that the cause of natural machines something like a human mind, but very much greater.

Cleanthes' argument is a genuine inductive argument, based on observation of the relation of cause and effect in the case of human production; Paley's is not.

There are of course many other objections which Hume marshals against the design argument, relating to the imperfections found in living things, the possibility that Nature may be capable of creating order by itself through some process as yet unknown to us, and the impossibility of inferring whether there is one Designer or several, or whether the Designer is benevolent, malevolent or indifferent. Suffice it to say that Paley addresses these objections at considerable length in his book. Another popular undergraduate-level objection, that living things reproduce and watches don't, is rebutted by Paley in Chapter II of his Natural Theology, in a devastatingly incisive fashion.

In the end, it seems to me that the fundamental disagreement between Hume and Paley is an epistemic one: it boils down to what justifies us in inferring the existence of an intelligent agent. Hume thinks that no structure, however complex it may be, can warrant a design inference on its own, and that we are only warranted in making such an inference if we know something about the goals, modus operandi and modus vivendi of the alleged designers; whereas Paley thinks that a system's having the property of being a contrivance is enough to warrant the inferential leap that it was designed.

Paley's final years

|

|

Left: Lincoln Cathedral (Western entrance). Image courtesy of Anthony Shreeve and Wikipedia.

Right: Lincoln Cathedral (view of the nave). Image courtesy of Tilman2007 and Wikipedia.

William Paley was appointed sub-dean of Lincoln Cathedral in 1795, ten years before his death, in recognition of his outstanding services to Christian apologetics, after having published A View of the Evidences of Christianity (1794), in which he argued for the truth of Christianity based on his understanding of historical evidence. Paley's work was considered to be of such excellent quality that it was added to the examinations at Cambridge, remaining on the syllabus until the 1920s.

Despite missing out on ecclesiastical promotion to the rank of bishop, Paley was showered with good fortune in the final years of his life, according to his Wikipedia biography:

For his services in defence of the faith, with the publication of the Evidences, the Bishop of London gave him a stall in St Paul's; the Bishop of Lincoln made him subdean of that cathedral, and the Bishop of Durham conferred upon him the rectory of Bishopwearmouth. The income he drew from these positions alone would have made him one of the wealthiest clergymen in England - wealthier than many bishops, and even some noblemen. But he also inherited several thousand pounds from his father-in-law, a commercial magnate, in the same year.

Paley's entry in the Dictionary of National Biography (vol. 43, pp. 100 ff.) is well worth a read, for those who are interested in learning more about the man and his ideas.

Paley's courage in the face of severe pain

What I found most moving, when researching Paley's life, was the fact that Paley wrote his Natural Theology, in which he not only argued for the existence of God, but defended His omnibenevolence, while he was suffering from kidney disease. He was frequently in great pain, and he had to write his Natural Theology during the brief intermissions from the pain he suffered. A lesser man might have been tempted to doubt the goodness of his Creator, but not Paley. He managed to rise above his illness, and pen the following passage, in which he explained why even pain provides us with an excellent argument for God's goodness:

Pain also itself is not without its alleviations. It may be violent and frequent; but it is seldom both violent and long-continued: and its pauses and intermissions become positive pleasures. It has the power of shedding a satisfaction over intervals of ease, which, I believe, few enjoyments exceed. A man resting from a fit of the stone or gout, is, for the time, in possession of feelings which undisturbed health cannot impart. They may be dearly bought, but still they are to be set against the price. And, indeed, it depends upon the duration and urgency of the pain, whether they be dearly bought or not. I am far from being sure, that a man is not a gainer by suffering a moderate interruption of bodily ease for a couple of hours out of the four-and-twenty. Two very common observations favour this opinion: one is, that remissions of pain call forth, from those who experience them, stronger expressions of satisfaction and of gratitude towards both the author and the instruments of their relief, than are excited by advantages of any other kind; the second is, that the spirits of sick men do not sink in proportion to the acuteness of their sufferings; but rather appear to be roused and supported, not by pain, but by the high degree of comfort which they derive from its cessation, or even its subsidency, whenever that occurs: and which they taste with a relish, that diffuses some portion of mental complacency over the whole of that mixed state of sensations in which disease has placed them.

(Natural Theology, 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, pp. 497-498)

The following passage attests to Paley's sunny disposition, even in the midst of affliction:

It is a happy world after all. The air, the earth, the water, teem with delighted existence. In a spring noon, or a summer evening, on whichever side I turn my eyes, myriads of happy beings crowd upon my view. "The insect youth are on the wing." Swarms of newborn flies are trying their pinions in the air. Their sportive motions, their wanton mazes, their gratuitous activity, their continual change of place without use or purpose, testify their joy, and the exultation which they feel in their lately discovered faculties. A bee amongst the flowers in spring, is one of the most cheerful objects that can be looked upon. Its life appears to be all enjoyment; so busy, and so pleased: yet it is only a specimen of insect life, with which, by reason of the animal being half domesticated, we happen to be better acquainted than we are with that of others. The whole winged insect tribe, it is probable, are equally intent upon their proper employments, and, under every variety of constitution, gratified, and perhaps equally gratified, by the offices which the Author of their nature has assigned to them.

(Natural Theology, 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, pp. 456-457.)

Without further ado, I'd now like to move on to discuss Paley's design argument.

If you've read anything about Paley's "design argument" for the existence of God, then you've probably heard it expressed in the following garbled form:

Rev. William Paley argued that there were strong similarities between complex structures that we find in Nature (such as the eye) and human artifacts, such as a watch. The human eye is like a machine, he claimed. So are the other organs of the body. But we already know from observation that mechanical artifacts, such as watches, are invariably designed by intelligent beings - namely, human beings. Operating on the principle, "like effects, like causes," we can infer by analogy that complex organs, such as the eye, were probably made by an Intelligent Designer, Who is like a human being, but much, much smarter. Since this inference is based on an inductive argument (rather than a deductive one) which makes use of an analogy, its conclusion is not absolutely certain. Nevertheless, maintained Paley, it is extremely probable that an Intelligent Designer exists. Paley then went on to argue that since the whole world is rather like a giant watch, we may legitimately conclude that the universe was made by a Designer - a Cosmic Watchmaker, if you like.

You've probably read about Hume's devastating rebuttal of the Design argument, which goes like this:

There are several flaws in Paley's Design argument, which were pointed out by the eighteenth century Scottish philosopher, David Hume.First, Paley's "watch analogy" for complex natural systems was never a very good one in the first place. The eye isn't a watch, and neither is the universe. The numerous disanalogies between complex natural structures (such as the eye) and a human artifact, undermine the inference that these natural structures were designed. The design inference is even weaker when we examine the universe as a whole: in reality, it is nothing like a watch.

Second, the numerous defects that we find in the organs of living things constitute powerful evidence against the hypothesis that they were designed by an Intelligent Creator.

Third, even if we had good evidence for an Intelligent Designer of Nature, our experience tells us that intelligent designers are invariably complex entities, so we would then have to ask: who designed the Designer? And who designed the Designer's Designer? And so on, ad infinitum. Wouldn't it be more rational, then, to simply say that Nature is self-ordering, instead of opening the door to an infinite regress of designers, which in the end, explains nothing?

Fourth, even if we could establish the existence of a Designer of Nature who can somehow avoid this infinite regress, we would still faced with another question: how can the Designer of Nature be a bodiless agent, as theists maintain? Our experience tells us that intelligent agents are always embodied beings, and nobody has ever seen a disembodied agent making anything. There is no good evidence for spooks. The notion of a spiritual Designer is therefore both absurd and unsupported by any credible evidence.

Fifth, even if could make sense of the notion of a spiritual Designer, how can we be sure that there's only one Designer of Nature? Might there not be many designers, as polytheism supposes?

Sixth, even if we could establish the unity of the Cosmic Watchmaker, such a Being would not need to be continually involved with the cosmos; maybe He created its complex systems at some point in the past, but He no longer interacts with the cosmos. So how do we know that the Designer of the cosmos is still alive?

Seventh, even if He still exists, we have no way of knowing whether the Cosmic Designer is a personal Being; for all we know, the Designer might be an impersonal force, like Spinoza's Deity.

Finally, even if we could establish that the Designer is a personal Being, there is no way of demonstrating that He is infinitely powerful, wise or good. The effects we see in Nature are finite, and from a finite effect, it is illicit to infer the existence of an Infinite Cause.

We can only conclude, then, that Rev. William Paley's identification of the Designer of Nature with the God of Judaism and Christianity in his Natural Theology is utterly unwarranted: it is a gigantic leap of faith which defies the laws of logic.

The above exposition of Paley's design argument contains several errors, which I've collected together under the heading of twelve myths, which are commonly found in discussions of Paley's argument for God's existence.

Myth One: Paley likens the world to a giant watch in his Natural Theology.

Fact: Paley explicitly rejected the analogy between the world and a watch, in his Natural Theology. He points out that when making design inferences, "we deduce design from relation, aptitude, and correspondence of parts." However, "the heavenly bodies do not, except perhaps in the instance of Saturn's ring, present themselves to our observation as compounded of parts at all," since they appear to be quite simple and undifferentiated in their internal structure (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 379). When discussing the movements of the heavenly bodies, he writes: "Even those things which are made to imitate and represent them, such as orreries, planetaria, celestial globes, &c. bear no affinity to them, in the cause and principle by which their motions are actuated" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 379) - the reason being that the mechanism of a watch requires that its parts be in physical contact with one another, whereas the gravitational influence exerted by one heavenly body on another is action at a distance.

Indeed, nowhere in his Natural Theology deos Paley declare that the world is like a watch. The closest statement I can find is his declaration, "The universe itself is a system; each part either depending upon other parts, or being connected with other parts by some common law of motion, or by the presence of some common substance" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXV, pp. 449-450). To be sure, Paley does argue that "In the works of nature we trace mechanism" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 416-418), but he never declares that Nature itself is one giant mechanism. Rather, Paley's proof of God was based on the existence of mechanisms (plural) occurring in the natural world.

What Paley does liken to watches are the biological structures (such as the eye) that we find in the natural world. For example, he writes that "very indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation," and in the same passage he adds that "here is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter III, pp. 17-18). Elsewhere, when discussing the example of the eye and other organs, he writes: "If there were but one watch in the world, it would not be less certain that it had a maker... Of this point, each machine is a proof, independently of all the rest. So it is with the evidences of a Divine agency... The eye proves it without the ear; the ear without the eye" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter VI, pages 76-77).

Myth Two: Paley's argument for a Designer in his Natural Theology is an argument from analogy.

Fact: Paley's argument is not based on any analogy. He doesn't say that the complex organs found in living things are like artifacts; he says that they are the same as artifacts in certain vital respects. In particular, these complex organs share several common properties with artifacts: "properties, such as relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413), or as he puts it elsewhere, "[a]rrangement, disposition of parts, subserviency of means to an end, [and] relation of instruments to a use" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter II, p. 11). Paley refers to the organs of the body as "contrivances," precisely because they share these vital properties with man-made artifacts. (For the benefit of Thomist readers who may be wondering, I should point out that Paley is fully aware of the teleology of living things, and that he repeatedly refers to "final causes" in his Natural Theology.)

Next, Paley argues that intelligence is the only known adequate cause of objects possessing the combination of properties found in artifacts and complex organs. Our experience tells us that that no other cause, apart from intelligence, is capable of producing effects possessing these properties. Paley concludes that the complex organs of living creatures (such as the eye) must therefore have had an Intelligent Designer. In his own words: "We see intelligence constantly contriving, that is, we see intelligence constantly producing effects, marked and distinguished by certain properties; not certain particular properties, but by a kind and class of properties, such as relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose. We see, wherever we are witnesses to the actual formation of things, nothing except intelligence producing effects so marked and distinguished. Furnished with this experience, we view the productions of nature. We observe them also marked and distinguished in the same manner. We wish to account for their origin. Our experience suggests a cause perfectly adequate to this account. No experience, no single instance or example, can be offered in favour of any other. In this cause therefore we ought to rest" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413-414).

For Paley, the inference to design, upon seeing a contrivance, is immediate:

This mechanism being observed (it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood), the inference, we think, is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker...Nor would it, I apprehend, weaken the conclusion, that we had never seen a watch made; that we had never known an artist capable of making one; that we were altogether incapable of executing such a piece of workmanship ourselves, or of understanding in what manner it was performed...

Ignorance of this kind exalts our opinion of the unseen and unknown artist's skill, if he be unseen and unknown, but raises no doubt in our minds of the existence and agency of such an artist, at some former time, and in some place or other. (Chapter I, pp. 3-4)

Myth Three: Paley put forward an inductive argument for a Designer: because there are complex systems in Nature which resemble human artifacts, which are made by intelligent agents, we can infer that an Intelligent Designer made Nature's complex systems.

Fact: Paley himself declares on several occasions that his argument for a Designer of Nature is a deductive argument. Thomist scholar Del Ratzsch, in his article on Teleological Arguments for God's Existence in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, also acknowledges that Paley's argument is a deductive one. Paley provides abundant confirmation of this fact in his Natural Theology. For example, he writes of "the marks of contrivance discoverable in animal bodies, and to the argument deduced from them, in proof of design, and of a designing Creator" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter IV, p. 67). Nowhere in his Natural Theology does Paley ever describe his argument as an inductive one.

The premises of Paley's deductive argument are as follows. First, we know that intelligent agents are capable of producing effects marked by the three properties of (i) relation to an end, (ii) relation of the parts to one another, and (iii) possession of a common purpose.

Second, no other cause has ever been observed to produce effects possessing these three properties.

We are therefore entitled to conclude that if there are systems in Nature possessing these same three properties, then the only cause that is adequate to account for these natural effects is an Intelligent Agent.

Myth Four: Paley's argument for God in his Natural Theology is a merely probabilistic argument, rather than a demonstrative proof.

Fact: Paley explicitly states, over and over again, that he views his argument for a Designer not as a merely probabilistic argument, but as a proof, whose conclusion was certain and indubitable. For example, in his discussion of the ligament of the ball-and-socket joint of the thigh, Paley declares that it provides us with unequivocal proof of a Creator: "If I had been permitted to frame a proof of contrivance, such as might satisfy the most distrustful inquirer, I know not whether I could have chosen an example of mechanism more unequivocal, or more free from objection, than this ligament" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter VIII, pp. 112-113). After describing the circulation of the blood, he writes: "Can any one doubt of contrivance here; or is it possible to shut our eyes against the proof of it?" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter X, p. 161).

Finally, in summing up his case, Paley wrote:

For my part, I take my stand in human anatomy: and the examples of mechanism I should be apt to draw out from the copious catalogue, which it supplies, are the pivot upon which the head turns, the ligament within the socket of the hip-joint, the pulley or trochlear muscles of the eye, the epiglottis, the bandages which tie down the tendons of the wrist and instep, the slit or perforated muscles at the hands and feet, the knitting of the intestines to the mesentery, the course of the chyle into the blood, and the constitution of the sexes as extended throughout the whole of the animal creation. To these instances, the reader's memory will go back, as they are severally set forth in their places; there is not one of the number which I do not think decisive; not one which is not strictly mechanical; nor have I read or heard of any solution of these appearances, which, in the smallest degree, shakes the conclusion that we build upon them.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 536).

Myth Five: Paley overlooked the numerous disanalogies between complex natural structures (such as the eye) and a human artifact, such as a watch. Additionally, his watch analogy for the cosmos was a very poor one.

Fact: As I demonstrated in my reply to Myth One above, Paley never likened the universe to a watch, so the objection against his watch analogy for the cosmos rests on a false premise.

As regards the organs of living things, Paley did indeed compare them to watches, but as I pointed out in my response to Myth Two above, Paley did not declare that the complex organs found in living things are like artifacts; rather, he says that they are the same as artifacts in certain vital respects. In particular, these complex organs share several common properties with artifacts: "properties, such as relation to an end, relation of parts to one another, and to a common purpose" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 413).

In a telling passage, Paley compares the eye to a telescope, and argues that despite the evident dissimilarities between the two, their common possession of the three properties described above, which characterize what he calls contrivances, warrants the inference that they were both intelligently designed:

As far as the examination of the instrument goes, there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it...To some it may appear a difference sufficient to destroy all similitude between the eye and the telescope, that the one is a perceiving organ, the other an unperceiving instrument. The fact is, that they are both instruments. And, as to the mechanism, at least as to mechanism being employed, and even as to the kind of it, this circumstance varies not the analogy at all. For observe, what the constitution of the eye is. It is necessary, in order to produce distinct vision, that an image or picture of the object be formed at the bottom of the eye. Whence this necessity arises, or how the picture is connected with the sensation, or contributes to it, it may be difficult, nay we will confess, if you please, impossible for us to search out. But the present question is not concerned in the inquiry...

In the example before us, it is a matter of certainty, because it is a matter which experience and observation demonstrate, that the formation of an image at the bottom of the eye is necessary to perfect vision... The formation then of such an image being necessary (no matter how) to the sense of sight, and to the exercise of that sense, the apparatus by which it is formed is constructed and put together, not only with infinitely more art, but upon the self-same principles of art, as in the telescope or the camera obscura. The perception arising from the image may be laid out of the question; for the production of the image, these are instruments of the same kind. The end is the same; the means are the same. The purpose in both is alike; the contrivance for accomplishing that purpose is in both alike. The lenses of the telescope, and the humours of the eye, bear a complete resemblance to one another, in their figure, their position, and in their power over the rays of light, viz. in bringing each pencil to a point at the right distance from the lens; namely, in the eye, at the exact place where the membrane is spread to receive it. How is it possible, under circumstances of such close affinity, and under the operation of equal evidence, to exclude contrivance from the one; yet to acknowledge the proof of contrivance having been employed, as the plainest and clearest of all propositions, in the other?

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter III, pp. 18-21)

Myth Six: Paley failed to address the argument that the numerous defects that we find in the organs of living things constitute powerful evidence against the hypothesis that they were designed by an Intelligent Creator.

Fact: Paley addressed this objection in the very first chapter of his Natural Theology, where he argued that someone who came across a watch lying in a field would still infer that it was designed, even if it contained defects. A badly designed object is still a designed object. In Chapter V, he returned to the objection, and allowed that imperfections might call God's skill, power or benevolence into question, but even so, countervailing evidence that convincingly attests to God's omniscience, omnipotence and omnibenevolence could outweigh the evidence against God's wisdom, power and goodness from the natural evils we observe in the world:

Neither, secondly, would it invalidate our conclusion, that the watch sometimes went wrong, or that it seldom went exactly right. The purpose of the machinery, the design, and the designer, might be evident, and in the case supposed would be evident, in whatever way we accounted for the irregularity of the movement, or whether we could account for it or not. It is not necessary that a machine be perfect, in order to show with what design it was made: still less necessary, where the only question is, whether it were made with any design at all.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter I, pp. 4-5)

When we are inquiring simply after the existence of an intelligent Creator, imperfection, inaccuracy, liability to disorder, occasional irregularities, may subsist in a considerable degree, without inducing any doubt into the question: just as a watch may frequently go wrong, seldom perhaps exactly right, may be faulty in some parts, defective in some, without the smallest ground of suspicion from thence arising that it was not a watch; not made; or not made for the purpose ascribed to it...

Irregularities and imperfections are of little or no weight in the consideration, when that consideration relates simply to the existence of a Creator. When the argument respects his attributes, they are of weight; but are then to be taken in conjunction ... with the unexceptionable evidences which we possess, of skill, power, and benevolence, displayed in other instances; which evidences may, in strength; number, and variety, be such, and may so overpower apparent blemishes, as to induce us, upon the most reasonable ground, to believe, that these last ought to be referred to some cause, though we be ignorant of it, other than defect of knowledge or of benevolence in the author.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter V, pp. 56-58)

Myth Seven: Paley's Intelligent Designer would still have to be complex, which means that on Paley's own logic, He would need to be designed, too.

Fact: Paley was well-aware of Hume's "infinite regress" objection, which has been popularized in our own day by Professor Richard Dawkins. He refuted it by denying its initial premise: he contended that the Designer must be immaterial and could not be composed of any complex contrivance of parts. Thus Paley's Designer is an immaterial, simple Being:

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He. The universe itself is merely a collective name: its parts are all which are real; or which are things. Now inert matter is out of the question: and organized substances include marks of contrivance. But whatever includes marks of contrivance, whatever, in its constitution, testifies design, necessarily carries us to something beyond itself, to some other being, to a designer prior to, and out of, itself. No animal, for instance, can have contrived its own limbs and senses; can have been the author to itself of the design with which they were constructed. That supposition involves all the absurdity of self-creation, i. e. of acting without existing. Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see. Which consideration contains the answer to a question that has sometimes been asked, namely, Why, since something or other must have existed from eternity, may not the present universe be that something? The contrivance perceived in it, proves that to be impossible. Nothing contrived, can, in a strict and proper sense, be eternal, forasmuch as the contriver must have existed before the contrivance.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412).

Myth Eight: Paley fails to address Hume's objection that in our experience, intelligent designers are always embodied beings, so the Intelligent Designer of Nature would need to be one, too.

Fact: Paley put forward two arguments for God's spirituality in his Natural Theology. First, he argued (following the opinion of most scientists of his day), that matter is essentially inert, in the sense that it is unable to make something move, unless something else first moves it. It follows that the ultimate source of motion in the cosmos must be something immaterial, or spiritual:

"Spirituality" expresses an idea, made up of a negative part, and of a positive part. The negative part consists in the exclusion of some of the known properties of matter, especially of solidity, of the vis inertiae, and of gravitation. The positive part comprises perception, thought, will, power, action, by which last term is meant, the origination of motion; the quality, perhaps, in which resides the essential superiority of spirit over matter, "which cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another (Note: Bishop Wilkins's Principles of Natural Religion, p. 106.)." I apprehend that there can be no difficulty in applying to the Deity both parts of this idea.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 448).

Second, Paley contended that the Designer of Nature could not be composed of any matter that was organized into contrivances made up of interacting parts, because then He would have to have been designed by some entity outside Himself, which would mean that He would no longer be self-existent:

Of this however we are certain, that whatever the Deity be, neither the universe, nor any part of it which we see, can be He. The universe itself is merely a collective name: its parts are all which are real; or which are things. Now inert matter is out of the question: and organized substances include marks of contrivance. But whatever includes marks of contrivance, whatever, in its constitution, testifies design, necessarily carries us to something beyond itself, to some other being, to a designer prior to, and out of, itself. No animal, for instance, can have contrived its own limbs and senses; can have been the author to itself of the design with which they were constructed. That supposition involves all the absurdity of self-creation, i. e. of acting without existing. Nothing can be God, which is ordered by a wisdom and a will, which itself is void of; which is indebted for any of its properties to contrivance ab extra. The not having that in his nature which requires the exertion of another prior being (which property is sometimes called self-sufficiency, and sometimes self-comprehension), appertains to the Deity, as his essential distinction, and removes his nature from that of all things which we see.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412).

Myth Nine: Paley's Design argument fails to establish that there's only one designer of Nature.

Fact: In his Natural Theology, Paley argued that the uniformity of the laws of Nature constituted the best evidence of the Creator's unity:

Of the "Unity of the Deity," the proof is, the uniformity of plan observable in the universe. The universe itself is a system; each part either depending upon other parts, or being connected with other parts by some common law of motion, or by the presence of some common substance...In our own globe, the case is clearer... We never get amongst such original, or totally different, modes of existence, as to indicate, that we are come into the province of a different Creator, or under the direction of a different will. In truth, the same order of things attend us, wherever we go.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXV, pp. 449-450)

The works of nature want only to be contemplated... We have proof, not only of both these works proceeding from an intelligent agent, but of their proceeding from the same agent; for, in the first place, we can trace an identity of plan, a connexion of system, from Saturn to our own globe: and when arrived upon our globe, we can, in the second place, pursue the connexion through all the organized, especially the animated, bodies which it supports. We can observe marks of a common relation, as well to one another, as to the elements of which their habitation is composed. Therefore one mind hath planned, or at least hath prescribed, a general plan for all these productions. One Being has been concerned in all.

(Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, pp. 540-541)

Myth Ten: Paley's God in his Natural Theology was only required to wind up the clockmaker universe at the beginning; after that, He is redundant, so we can't be sure if He still exists or not.

Fact: Paley, like most of his contemporaries, believed that a material object is incapable of making another object move, unless it is moved by something else. As he puts it, matter "cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 412). Since bodies are incapable of initiating motion, Paley concludes that the bodies in the cosmos can only act upon each other if something immaterial is continually acting on them. We also find that bodies throughout the natural world whose parts are arranged in a complex manner, enabling them to work together for a common end. Experience tells us that intelligent agency is the only cause which is capable of producing systems with this combination of properties. From this, we may deduce that the Immaterial Agent that keeps the world moving is also an Intelligent Agent. In Paley's words: "In the works of nature we trace mechanism; and this alone proves contrivance: but living, active, moving, productive nature, proves also the exertion of a power at the centre: for, wherever the power resides, may be denominated the centre" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 418).

Another problem with the objection is that it assumes Paley thought he could prove the universe had a beginning. In fact, he argued that even if it were eternal, it would still require a Designer:

Nor is any thing gained by running the difficulty farther back, i. e. by supposing the watch before us to have been produced from another watch, that from a former, and so on indefinitely. Our going back ever so far, brings us no nearer to the least degree of satisfaction upon the subject. Contrivance is still unaccounted for. We still want a contriver. A chain, composed of an infinite number of links, can no more support itself, than a chain composed of a finite number of links. (Chapter II, pp. 12-13)The machine which we are inspecting, demonstrates, by its construction, contrivance and design. Contrivance must have had a contriver; design, a designer; whether the machine immediately proceeded from another machine or not. That circumstance alters not the case. That other machine may, in like manner, have proceeded from a former machine: nor does that alter the case; contrivance must have had a contriver. That former one from one preceding it: no alteration still; a contriver is still necessary. No tendency is perceived, no approach towards a diminution of this necessity. It is the same with any and every succession of these machines; a succession of ten, of a hundred, of a thousand; with one series, as with another; a series which is finite, as with a series which is infinite. (Chapter II, pp. 13-14)

Our observer would further also reflect, that the maker of the watch before him, was, in truth and reality, the maker of every watch produced from it; there being no difference (except that the latter manifests a more exquisite skill) between the making of another watch with his own hands, by the mediation of files, lathes, chisels, &c. and the disposing, fixing, and inserting of these instruments, or of others equivalent to them, in the body of the watch already made in such a manner, as to form a new watch in the course of the movements which he had given to the old one. It is only working by one set of tools, instead of another. (Chapter II, p. 16)

Myth Eleven: Paley's God in his Natural Theology is an impersonal Designer, and not the God of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Fact: Paley argued that God must be a personal Being, because He is capable of designing things. As he put it: "that which can contrive, which can design, must be a person" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, p. 408). A designer, by definition, possesses consciousness and thought, and must be capable of perceiving a goal or end, and adapting and directing means to achieve this goal. Such a being, Paley argued, must be a person (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, pp. 408, 441).

Myth Twelve: At most, Paley's design argument establishes only the existence of a finite, limited Deity, which falls short of the Infinite God of classical theism.

Fact: A careful examination of Paley's writings shows that he put forward no less than four arguments for God's infinity, in his Natural Theology.

First, using the example of the eye, Paley argued that God's designs are infinitely more skillful than our own (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter III, p. 21).

We can also discern a second argument for God's infinite intelligence in Paley's observation that when God selected the laws of Nature, He had to make a choice from among an infinite number of alternatives, only an infinitesimal proportion of which were compatible with the formation of a stable cosmos (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXII, p. 393).

Third, Paley argued that God must be infinitely powerful, because He is able to control an indefinitely large region of space by His volitions: His power extends everywhere.

Fourth, Paley considered that God must be infinitely wise, because He is apparently capable of manifesting His wisdom and benevolence in an unlimited number of ways, and upon an unlimited number of objects (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVI, p. 492; Chapter XXVII, p. 548).

Professor Edward Feser, a leading Thomistic critic of Intelligent Design. Image taken from http://www.edwardfeser.com/.

At the beginning of this post, I accused Professor Feser of having completely misread Paley's Natural Theology I am perfectly well aware that to accuse a Professor of Philosophy of having totally misunderstood an author like William Paley is a pretty impertinent thing to do - especially when the accusation is made by a non-academic like myself. Nevertheless, it is something which I feel impelled to do, out of a sense of duty. Professor Feser has made a number of statements (see here and here for examples) about Rev. Paley's philosophical views, and in particular his argument from design, which are flat-out false: they totally contradict what Paley himself says in his own writings. It is quite remarkable that Feser has managed to misconstrue Paley's meaning, for Paley wrote his Natural Theology in the most pellucid prose imaginable. I sincerely hope that after reading this post, Professor Feser will issue a retraction of his false statements about Paley, and offer a posthumous apology to the man.

Where did Feser get his mistaken ideas about Paley's design argument?

In his writings elsewhere on Paley, Professor Feser leans heavily on the interpretation given to his writings by other Christian (and especially Aristotelian-Thomistic) philosophers - an interpretation which I shall argue below is utterly wrong-headed. Indeed, Feser leans so heavily on the wrong-headed interpretation of Paley by these secondary sources that at first, I wondered whether he had actually read Paley's Natural Theology. However, since his 2011 Reply to Marie George makes it quite clear that he has read Paley, then I have no option but to accuse Professor Feser of having read Paley in a very uncharitable manner - which is precisely the fault that he takes Professor George to task for, in her discussion of articles written by him! In this post, I shall endeavor to persuade Feser that his reading of Paley is wholly mistaken.

I would also like to offer some advice to Professor Feser about reading an author: if you want an unprejudiced view of an author, then it is best to read the author first and form your own views of what he meant, before reading what others have written about him. Paley wrote his treatise, not in Greek or Latin, but in English, and in a very clear style of prose at that. The possibility of mistaking his meaning is greatly reduced if you read him before reading what his commentators - friendly or hostile - have to say about him.

I should add that I was fortunate enough to read Paley online. I was thus able to do a word search of terms like "probability", "proof", "analogy" and so on. This proved to be of invaluable assistance, as it enabled me to spot patterns in Paley's usage of these terms, that I might not have noticed otherwise.

Let us now examine the authors cited by Feser in support of his bizarre reading of Paley.

In his online post, Thomism versus the design argument (March 15, 2011), Professor Feser approvingly cites several passages from Thomistic authors who denigrate Paley's argument. Here's a passage he quotes from An Elementary Christian Metaphysics, by Joseph Owens:

This argument [St. Thomas Aquinas' Fifth Way] is clearly not the argument from design, made notorious by Paley... Paley's argument is only an analogy, a probable argument. It is not a metaphysical demonstration... Paley merely multiplies instances upon instances of design in nature in order to drive home the impression... that a designer is required. The starting point of St. Thomas's fifth way, on the other hand, is not that things show design, but rather that something is being done to them, namely, that they are being directed to an end by an efficient cause. (Center for Thomistic Studies, 1985, p. 349)

And here's a brief excerpt from another passage cited by Feser, taken from Thomas Aquinas: God and Explanations by Professor Christopher F. J. Martin, (Edinburgh University Press, 1998, pp. 180-82):

It is no coincidence that the most famous presentation of the argument from design actually compares the world to a clock: it is known by the name of Paley's watch...The Being whose existence is revealed to us by the argument from design is not God but the Great Architect of the Deists and Freemasons, an impostor disguised as God, a stern, kindly, and immensely clever old English gentleman, equipped with apron, trowel, square and compasses....

The Great Architect is not God because he is just someone like us but a lot older, cleverer and more skilful. He decides what he wants to do and therefore sets about doing the things he needs to do to achieve it. God is not like that... God is mysterious: the whole objection to the great architect is that we know him all too well, since he is one of us.

I have already criticized Martin for his historical inaccuracy in the above passage. For example, the title "Great Architect" goes back to John Calvin, not the Masons, and artistic depictions of God as an architect date from as far back as the thirteenth century.

Feser also quotes from Fr. Ronald Knox, who describes Paley's argument from design as a "feeble argument" in his book, Broadcast Minds. In his book, The Belief of Catholics, Fr. Knox has this to say about Paley's argument:

This [Aquinas'] argument from the order and systems to be found in Creation is not synonymous with the argument from design; the argument from design, in the narrow sense, is a department or application of the main thesis. Design implies the adaptation of means to ends; and it used to be confidently urged that there was one end which the Creator clearly had in view, the preservation of species, and one plain proof of his purposive working, namely, the nice proportion between the instincts or endowments of the various animal species and the environment in which they had to live. The warm coats of the Arctic animals, the differences of strength, speed, and cunning which enable the hunter and the hunted to live together without the extermination of either--these would be instances in point; modem researches have given us still more salient instances of the same principle, such as the protective mimicry which renders a butterfly or a nest of eggs indistinguishable from its surroundings. Was it not a Mind which had so proportioned means to ends?The argument was a dangerous one, so stated. It took no account of the animal species which have in fact become extinct; it presupposed, also, the fixity of animal types. God's mercy, doubtless, is over all his works, but we are in no position to apply teleological criticism to its exercise, and to decide on what principle the wart-hog has survived while the dodo has become extinct. In this precise form, then, the argument from order has suffered badly. But the argument from order, as the schoolmen conceived it, was and is a much wider and less questionable consideration. It is not merely in the adaptation of means to ends, but in the reign of law throughout the whole field of Nature, that we find evidence of a creative Intelligence.

In fact, while Paley does assert in passing (pp. 352, 480, 506) that species never die out, this assertion is incidental to his central argument, which is that Nature contains contrivances, and that intelligence is the only cause known to be capable of producing contrivances.

Moreover, Paley himself argued from the occurrence of uniform laws of Nature to the existence of a Deity. I conclude that Fr. Knox had only a passing familiarity with Paley's work.

It is a great pity that Feser has allowed himself to be influenced by writers who never studied Paley's arguments in detail.

How does Feser perpetuate myths about Paley's design argument?

Not only does Professor Feser enthusiastically cite Scholastic authors who have misread Paley, but he wholeheartedly endorses their misrepresentation. In his book, Aquinas (Oneworld, Oxford, 2009, p. 115), Feser offers his own perspective on William Paley's argument from design, in the following paragraph:

Paley, taking for granted as he does a modern mechanistic view of nature, denies that purpose or teleology is immanent or inherent to the natural order. That is why his argument is a merely probabilistic one. The design argument allows that there might in fact be no purpose at all in the natural world, but only the misleading appearance of purpose; its claim is simply that, at least where complex mechanistic processes are concerned, this supposition is unlikely. And even if there is a purpose, it is imposed from outside, in just the way a human watchmaker imposes a certain order on metal parts that have no inherent tendency to function as a timepiece. The natural world remains as devoid of immanent teleology after the designer's action as before. Moreover, as with a watch, once Paley's designer has done his "watchmaking," there is no need for him to remain on the scene, for once built the mechanism can function without him.

As we shall see, the above passage egregiously misrepresents Paley's argument in his Natural Theology.

Professor Feser repeats his misconstrual of Paley's design argument in a recent article entitled, "Teleology: A Shopper's Guide" (Philosophia Christi 12 (2010): 142-159). Here are some examples:

Aristotelian teleological realism ... holds ... that teleology is both immanent to the natural world and in need of no further explanation, divine or otherwise. One of the differences between Paley and ID [Intelligent Design] defenders on the one hand, and A-T [Aristotelian-Thomistic] defenders of Aquinas's Fifth Way on the other, is that the latter acknowledge the Aristotelian challenge and take it seriously. The reason is that they reject the mechanistic conception of nature held in common by naturalists on the one hand and Paley and ID defenders on the other — a conception which, by definition, rules out from the start the Aristotelian view that teleology is immanent to natural substances. (p. 153)...[F]or ID theory as for Paley, it is (contrary to the A-T position) at least possible that natural substances have no end, goal, or purpose; they just think this is improbable. The reason is that their essentially mechanistic conception of nature leads them to model the world on the analogy of a human artifact. The bits of metal that make up a watch have no inherent tendency toward functioning as a timepiece; it is at least theoretically possible, even if improbable, that a watch-like arrangement might come about by chance. (p. 154)

[Aquinas] says that unintelligent natural objects cannot move towards an end unless directed by an intelligence, not that it is highly improbable that they will do so... It is not an inductive generalization at all, nor an argument from analogy, nor an argument to the best explanation... This is a metaphysical assertion, not an exercise in empirical hypothesis formation. (p. 157)

The argument [of Aquinas] differs from Paley-style design arguments and the arguments of ID theorists in ways other than those already mentioned. For example, since the entities comprising the natural world have the final causes they have as long as they exist, the intellect in question has to exist as long as the natural world itself does, so as continually to direct things to their ends. The deistic notion that God might have "designed" the world and then left it to run independently is ruled out. Here, as in the other main Thomistic arguments for God's existence, the aim is to show that God is a sustaining or conserving cause of the world rather than that He got the world started at some point in the past. (pp. 158-159)

In a nutshell, what is wrong with Professor Feser's analysis of Paley's argument?

The errors in Feser's misreading of Paley can be grouped under five main headings.

Feser's first error lies in his astonishing assertion that Paley denied that natural objects possess any immanent causal powers of their own. The absurdity of this charge should be evident to anyone who has read Paley's Natural Theology: there are dozens of passages in the book which clearly indicate that Paley believed that natural objects possessed powers in their own right - active as well as passive. For example, Paley refers to the "powers of nature which prevail at present" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, page 440) and he writes about "gravity, magnetism, electricity; together with the properties also and powers of organized substances, of vegetable or of animated nature" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIV, page 446). Paley's view of living things is also clearly teleological. For example, in his Natural Theology, he describes the process by which living things nourish themselves, as follows:

Unconscious particles of matter take their stations, and severally range themselves in an order, so as to become collectively plants or animals, i.e. organized bodies, with parts bearing strict and evident relation to one another, and to the utility of the whole. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, page 420).

What Paley denied, however, was that natural objects lacking intelligence could possess any built-in powers to adapt means to ends, as such, or to assemble themselves into intricate arrangements of parts which are adapted to some common end. That is what Paley means when he scoffs at the notion of "a principle of order in nature" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter V, page 71). Paley is simply asserting that Nature doesn't possess any magical powers.

Second, Feser's claim that Paley's argument for a Deity in his Natural Theology is "a merely probabilistic one" is contradicted over and over again, in passages which make it clear that Paley envisaged his argument as nothing less than a positive proof of God's existence. For example, he refers to "the marks of contrivance discoverable in animal bodies, and to the argument deduced from them, in proof of design, and of a designing Creator" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter IV, page 67) and when discussing the example of the eye, he writes:

"If there were but one watch in the world, it would not be less certain that it had a maker... Of this point, each machine is a proof, independently of all the rest. So it is with the evidences of a Divine agency... The eye proves it without the ear; the ear without the eye." (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter VI, pages 76-77.)

Paley maintained that design without a Designer is impossible, and not merely improbable. I am at a loss to imagine how Feser could have overlooked passages like these.

Third, Feser's assertion that "it is at least theoretically possible, even if improbable, that a watch-like arrangement might come about by chance" is contradicted by no less an authority than St. Thomas Aquinas himself, in his Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics, Book 7, Lesson 8, paragraph 1436, where he writes that "some things, for instance, health, sometimes come to be by art and sometimes by chance, while others, for instance, a house, come to be only by art and never by chance." Aquinas goes on to give the reason: "in the case of stones and timbers there is no active power by which the matter can be moved to receive the form of a house" (paragraph 1438), and he adds: "Therefore those artificial things which have this kind of nature, such as a house made of bricks, cannot set themselves in motion; for they cannot be moved unless they are moved by something else" (paragraph 1440).

It gets better. Aquinas goes on to give an example from biology, in his discussion of the "higher" animals, which Aristotle referred to as perfect animals - a term which roughly corresponds to what we call mammals. Aquinas maintains that while these animals have a natural power of generating themselves through sexual reproduction, they are incapable of originating through spontaneous generation: "But those things whose matter cannot be moved by itself by that very motion by which the seed is moved, are incapable of being generated in another way than from their own seed; and this is evident in the case of man and horse and other perfect animals" (paragraph 1454). The reason, as he explains in his Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics, Book 7, Lesson 6, paragraph 1401, is that "the more perfect a thing is, the more numerous are the things required for its completeness." If this is not a Paleyan argument, then I don't know what is.

Fourth, although Paley envisaged the purposes of living creatures' organs as having been "imposed from outside", they were nonetheless inherent to those creatures. As I argued in Parts One and Three above, it makes perfect sense to speak of an externally imposed power as being inherent to a creature.

Finally, Paley's Designer is no absentee Deity, who wanders away from His creation after he has finished his "watchmaking." In his Natural Theology, Paley argues that God is needed to maintain the cosmos at every moment of its existence, and that nothing could continue working without him. Paley, like Aquinas, believed that matter "cannot move, unless it be moved; and cannot but move, when impelled by another" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, page 448.) Spirit, on the other hand, is self-moving, and this power of originating motion is "the quality, perhaps, in which resides the essential superiority of spirit over matter" (ibid.) Hence for Paley it follows that something extraneous to the material world is continually required to keep it moving: "In the works of nature we trace mechanism; and this alone proves contrivance: but living, active, moving, productive nature, proves also the exertion of a power at the centre: for, wherever the power resides, may be denominated the centre." (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXIII, page 418.) Later, Paley specifically declares that God conserves things in existence: he refers to God as "the Preserver of the world" (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XVII, page 298) and writes: "Under this stupendous Being we live. Our happiness, our existence, is in his hands. All we expect must come from him. (Natural Theology. 12th edition. J. Faulder: London, 1809, Chapter XXVII, p. 541)

Professor Feser's complete misreading of Paley's argument can best be illustrated by setting forth fourteen theses, which I have drawn from Paley's work, and which I will establish below, with supporting quotes:

| Thesis 1. For Paley, the inference to an Intelligent Designer of Nature is absolutely certain and not merely probable. This deductive inference is based on the fact that intelligence is capable of producing systems whose parts are intricately arranged and co-ordinated so as to serve some common end, coupled with the fact that nothing else is capable of producing these systems. If inferences of this kind were not valid, argues Paley, then an absurd consequence would follow: that no co-ordinated arrangement of parts subserving some end could ever suffice to establish the existence of an intelligent designer, no matter how intricate the arrangement was. |

| Thesis 2. For Paley, the organs of living things are the best possible proof of the Designer's existence, because they furnish numerous examples where a large number of parts are intricately arranged and exquisitely adapted as means to some end (of the organism), thereby clearly indicating to even the dullest observer that an Intelligence was required to produce them. The term contrivance, as used by Paley, denotes not an artificial contraption, but a co-ordinated arrangement of parts subserving some end. Paley insists that "the contrivances of nature surpass the contrivances of art"; hence the intelligence required to produce them is super-human. |

| Thesis 3. Paley contends that the laws of Nature show signs of having been chosen by an Intelligent Agent, as well. They are finely tuned: out of an infinite number of possible laws, those laws which allow the existence and continuation of a stable cosmos are very few, and those which support life are even fewer. If we look at physical systems within our universe (e.g. solar system), we find that the initial conditions required to form such systems were also fine-tuned. Since the laws of Nature hold throughout the cosmos, it follows that the Intelligent Agent responsible for them must exist outside and beyond Nature. |

| Thesis 4. In response to those who would explain the harmony of the cosmos by appealing to laws, Paley argues that laws and mechanisms are incapable of explaining anything, in the absence of agency. Properly understood, a law or mechanism simply refers to the way in which the power of some agent operates. It therefore follows that no law or mechanism in Nature can ever do away with the need for an original Designer; nor is it capable of doing the Designer's work in his absence. Thus the Designer cannot just wander off, after establishing the laws of Nature; nothing would work if He did. |

| Thesis 5. Paley, like Aquinas, holds that a body is incapable of making another body move, unless it is currently being moved by something else. It follows that if we find contrivances in Nature which are moving, there must exist something which is currently making them move. This fact is of vital importance, for it establishes without a doubt that the Intelligent Designer of Nature is still alive. According to Paley, the agency of this Intelligent Designer is continually required, in order to explain the ongoing movements of the numerous contrivances we find in Nature. |