Preamble

Emotions, and feelings in general, are often used to drive an ontological wedge between a subjects, which possess some kind of mental life, and are described using first-person terminology, and mindless objects, which are more appropriately described by third-person terminology. The argument of this thesis is that the "I versus "it" (first-person vs. third-person) divide is dwarfed by the gulf between what I shall call the "it" vs. "they" (third-person-singular vs. third-person-plural) divide: that is, between organisms, which behave as co-ordinated wholes, and artefacts, which lack intrinsic unity and behave as assemblages. As we argued in chapter one, the unity of a living thing is reflected in the nested functionality of its parts, which subserve the good of the whole.

Insofar as they pursue those things which are in their interests, all life-forms have something analogous to emotions. The humble E. coli bacterium, which is attracted to lactose but averse to benzoate, and which prefers glucose to lactose, lacks "feelings", but it does possess a feature of emotions that is much more important than mere subjectivity: it can be moved towards or away from some object that in which it has an interest.

Methodological presuppositions

At the outset of this enquiry into animal emotions, I shall attempt to set forth my background assumptions.

(a) Animal Emotions are Real

In this chapter, I shall take it as a "given" that at least some animals - in particular, some mammals and birds - have emotions. (Whether these emotions are phenomenologically conscious is a matter I will discuss later.) This decision can be defended on linguistic and psychological grounds, even before we attempt to define emotions.

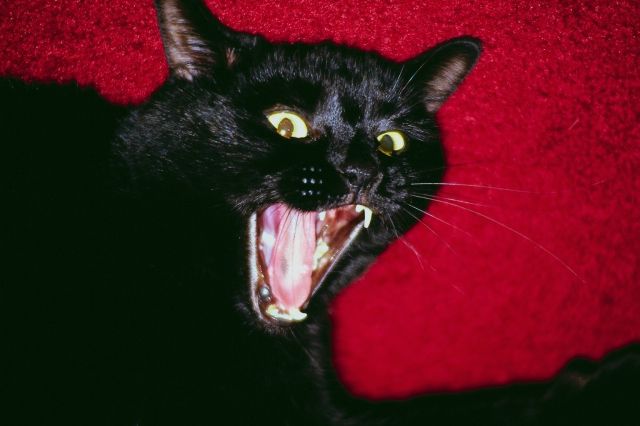

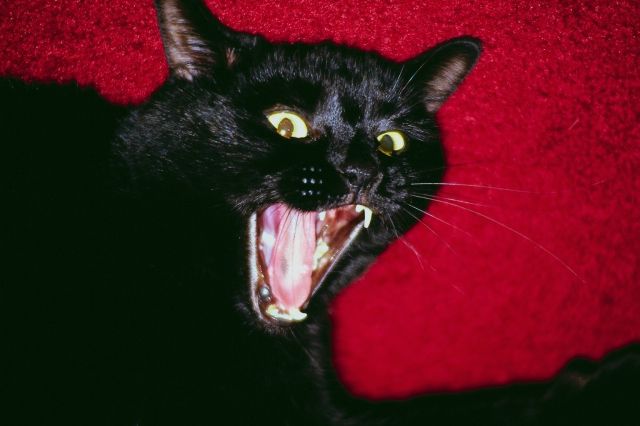

Animal emotions are a linguistic "given". Ceasing to recognise emotions in mammals and birds would do violence to the way we talk about emotions, because these animals often serve as primary referents for words describing emotions. If I were teaching a child the meaning of anger, I could do no better than to point to a hissing, snarling cat and say: "This is what anger looks like." Here, the angry cat functions as an exemplar. Additionally, the fact that all human languages possess an abundance of animal metaphors for emotions makes it impossible to divorce the meaning of these emotions from animal behaviour.

Emotions in some mammals and birds are also a psychological "given". Recent research has established that humans and their companion animals are emotionally symbiotic: each needs the other to thrive emotionally. Put simply, our own feelings feed off those of our pets, and therefore cannot be defined apart from them. Midgley (1993) summarises the evidence:

Pet therapy programs... caused a disturbance as soon as they began to be reported some years back, because they call in question the human race's boasted independence and autonomy. Could the undignified suggestion that people actually needed and welcomed the gifts of these unworthy, alien beings really be true? Repeated investigations have confirmed that it is indeed true... The idea that pet-keeping was some sort of pointless aberration, a meaningless, sentimental, perverse fad of the affluent West, can scarcely now be defended. The therapeutic effectiveness of pet-keeping, along with anthropological data showing that pets have been kept in all kinds of human societies, is gradually forcing attention to the meaning of such customs.

I am not claiming here that all pets have emotions simply because their owners bond with them. Rather, my point is that the vast majority of pet owners find that their own emotional well-being is enhanced by interacting with their pets. The most reasonable explanation of this fact is that most pet owners' feelings are reciprocated to some degree by their pets.

It should not be assumed, however, that animal emotions share all of the properties of human emotions.

(b) General Properties of Emotions

Emotions are the subject of long-standing philosophical controversy. However, one recent positive development is that philosophers have come to agree on several key points, highlighted by de Sousa (2003):

(Ronald de Sousa

on a good day)

(Ronald de Sousa

on a good day) (and on

not such a good day)

(and on

not such a good day)A broad consensus has emerged on what we might call adequacy conditions on any theory of emotion. An acceptable philosophical theory of emotions should be able to account at least for the following nine characteristics...I have argued that emotions in at least some mammals and birds must be genuine. However, to impute rationality, morality or language to all of these animals would be clearly anthropomorphic. I therefore conclude that any features of emotions in de Sousa's list that make explicit mention of rationality (i.e. the third and eighth items), morality (the last item) or language (the fourth item, which appears to rely on the subject's verbally reported "quality of life") cannot be necessary features of emotions per se, although certain emotions (e.g. remorse and pride) obviously require them. (I shall respond below to arguments claiming that the attribution of any emotion to an individual presupposes that it is rational or can use language.)

- emotions are typically conscious phenomena; yet

- they typically involve more pervasive bodily manifestations than other conscious states;

- they vary along a number of dimensions: intensity, type and range of intentional objects, etc;

- they are reputed to be antagonists of rationality; but also

- they play an indispensable role in determining the quality of life;

- they contribute crucially to defining our ends and priorities;

- they play a crucial role in the regulation of social life;

- they protect us from an excessively slavish devotion to narrow conceptions of rationality;

- they have a central place in moral education and the moral life (de Sousa, 2003, italics mine).

That leaves five features of interest to us:

(c) Animal emotions, whether conscious or not, are mental states amenable to scientific investigation

While human emotions are indeed typically (if not always) conscious, the question of whether phenomenal consciousness is an essential feature of animal emotions remains a contentious one among philosophers and scientists. The consensus view of most psychologists is that the very concept of an unconscious emotion is an oxymoron (Berridge, 2003c).

There are several reasons for querying this consensus. First, within the discipline of neurology, unconscious emotions are not regarded as an anomaly. For instance, LeDoux (1998) argues that emotions are adaptive because of the way they work within the body, not because of the way they consciously feel:

Emotions evolved not as conscious feelings... but as brain states and bodily responses. The brain states and bodily responses are the fundamental facts of an emotion, and the conscious feelings are the frills that have added icing to the emotional cake... (1998, p. 302).

Second, research has conclusively demonstrated that normal human beings are capable of acting on emotions that they are not consciously aware of. Berridge (2003b) describes a study in which subliminal exposure to happy or angry faces - which the subjects were later unable to recall - had a dramatic influence on their liking for a fruit beverage, how much they they wanted to consume, and how much they would be willing to pay for it if it were sold (i.e. its monetary value). Berridge refers to these phenomena as "nonconscious 'liking' and 'wanting'".

Third, emotional facial reactions are known to occur even in human infants who, according to the American Medical Association and American Academy of Neurology (Shewmon, 1999), are congenitally incapable of consciousness, as their brains lack cerebral hemispheres and possess only a functioning brainstem. Thus the parts which are supposed to mediate cognition, the social emotions and the evaluation of the emotional significance of stimuli are missing. Research cited by Berridge (2003b) shows that anencephalic infants display positive facial reactions (e.g. lip sucking, smiles) to sweet tastes and negative reactions (e.g. gapes, nose wrinkling) to bitter tastes. Berridge concludes that the core of the facial reaction to sweet and bitter tastes is a nonconscious one. On the other hand, Shewmon (1999) argues strongly that these infants do indeed possess a rudimentary consciousness.

To avoid biasing my methodology, I shall adopt a broad definition of animal emotions: animal emotions may or may not be conscious, but at a minimum, they must be mental states which are amenable to scientific investigation. Whatever they are, emotions must in some way be psychological states as well as physical ones, for that is how the word "emotion" is used in our language. Also, the fact that there are several well-established scientific disciplines that deal with emotions attests to their amenability to scientific investigation.

Many people, on the other hand, adhere to a "subjectivist" account of feelings, claiming that emotions and other feelings (such as pain) designate private sensations. These private inner states are said to be inaccessible to scientific investigation. However, Leahy (1994, p. 124) argues that this conviction arises from focusing exclusively on isolated feelings such as toothaches. On this point, Leahy cites a supporting comment from Wittgenstein and comments:

'A main cause of philosophical disease - a one-sided diet: one nourishes one's thinking with only one kind of example' (PI 593). The question we must ask is, 'How does a human being learn the meaning of the names of sensations? - of the word "pain" for example' (1994, p. 124).Similar observations apply to animal emotions (Leahy, 1994, p. 128). The key point here is that if emotions were inherently private, it would be impossible for us to learn the meanings of the words used to designate them. But in fact, emotions are often defined ostensibly in a public context: "This is what anger looks like". We may even use animals as paradigm cases of these emotions.

The subjectivist account of emotions also fails to explain how outward bodily states are able to manifest these allegedly private inner feelings, or why there should be different kinds of emotions, or what makes private inner states possess the property of "aboutness", or how such essentially private states can have an important social role.

At the other extreme, I reject any accounts of emotions which define them purely in terms of outward behavioural dispositions and thus fail to explain why emotions should be treated as mental states at all. Dispositions do not require a mentalistic explanation: as we saw in chapter two, a mind-neutral goal-centred intentional stance can be used instead.

Thus I propose to re-write the first of our five selected features of animal emotions as follows:

Animal emotions, whether conscious or not, are mental states which are amenable to scientific investigation.

We therefore have to consider the possibility that there may be animals who have non-phenomenal emotions - emotions without any conscious feelings whatsoever.

(d) Animal emotions have intentional objects

Much of the argumentation in this chapter rests upon the assumption, which I defended in chapter two, that Daniel Dennett's intentional stance can be applied to all kinds of mental states, including emotions. In other words, emotions, like beliefs, desires and other mental states, have to be "about" something: they require intentional objects. As Leahy (1994) puts it:

[S]omeone who announced that they were afraid, or hoping, or feeling, but seemed unable to tell us any more would indeed be a source of perplexity. A person should be able to say what they are afraid of, hoping for, or feeling guilty about... The emotions, or most of them, are said to be directed, and to have objects (1994, p. 130).

Even individuals (including animals) who cannot tell us what the objects of their emotions are can still be said to have directed feelings:

The targets of an animal's fear or anger are usually clear enough and it is perfectly natural and necessary to speak of them... Herring gulls with wings held 'akimbo' are poised to hurl themsleves at an intruder" (Leahy, 1994, p. 135).

There are, however, situations where we experience emotions without any apparent object. Sometimes, for instance when we experience an undefined feeling of fear, there may be an object but we may not be consciously aware of what it is, because the brain registers it at a subconscious level. Other emotions, such as an ill-defined feeling of depression, resist characterisation in intentionalist terms, as they lack any kind of object whatsoever.

We could deal with these object-less emotions by differentiating them from emotions proper, and placing them in a separate category, e.g. "moods" (de Sousa, 2003), but this seems a rather artificial manoeuvre.

Alternatively, we could assimilate object-less emotional states to emotions of the same kind that have an object, by virtue of the strong "family resemblance" between the former and the latter, but at the cost of having to deny that the class of emotions designates a natural category. The decision to include a mental state as an emotion would be made within the context of a "language game". This flies in the face of neurological evidence (to be presented below) indicating that emotional states are sharply distinguished from cognitive states, and that the different kinds of emotions are also fairly well-defined.

Finally, we could differentiate between specific emotions and kinds of emotions (de Sousa, 2003). The former may lack an object; the latter cannot.

Philosophers speak of each kind of emotion as having a formal object which defines what it is. De Sousa (2003) describes this object as "a property implicitly ascribed by the emotion to its target, focus or propositional object, in virtue of which the emotion can be seen as intelligible". For instance, my fear of a snake only makes sense because I construe certain properties of the snake as frightening.

But it does not help us much to say that we fear snakes because we think they are frightening. To make sense of our fear - or indeed, any kind of emotion - we need to know what it is for. The only standard by which we can judge the appropriateness of an animal's emotional responses is its own well-being. Since we cannot ask non-human animals lack language, we have to assess their well-being from an external, scientific standpoint. Accordingly, I envisage the object of each kind of emotion not merely as a formal object, but as a teleological object that explains what the emotion is "for" and how it helps the animal to survive and/or flourish. Each kind of emotion is "for" responding appropriately to a certain kind of object, which I propose to call the generic intentional object of the emotion. This generic object is what the emotion is about. Fear, for instance, is "about" objects recognised as dangerous, and it is for responding appropriately to them. That is what makes it different from anger.

The purpose (i.e. intrinsic finality) of each kind of emotion can be explained in Darwinian terminology. Below, I shall defend the view that the generic intentional object of each kind of emotion is simply the kind of environmental challenge that the emotion evolved to meet.

Object-less feelings are therefore derivative upon directed feelings. I propose that the ascription of object-less feelings to a non-human animal can only take place after we have identified:

(i) emotions of the same kind in that animal, that are "directed" at something;(ii) the generic intentional object of the kind of emotion the animal is feeling; and

(iii) non-arbitrary, teleological criteria which allow us to identify the different kinds of emotions as natural categories.

The advantages of the approach defended here can best be seen by contrasting it with a behavioural approach to the emotions. The latter approach would allow us to define individual emotions as behavioural dispositions towards their intentional objects, conceived as external to the animal - e.g. an animal's movement towards (or away from) X for the sake of obtaining (or avoiding) X, is "about" X. Although this account incorporates intentionality (by stipulation), it cannot explain object-less emotions, such as undirected feelings of fear or depression.

Another drawback of this account is that it defines "aboutness" in purely non-mentalistic terms: bacteria can also move towards their objects, for the sake of obtaining them.

But perhaps the most serious problem with this behaviourist approach to intentionality is that it says nothing about the different kinds of emotions. Distinctions have practical significance here. For instance, the question of whether fear and panic are different emotions or two versions of the same emotion is not a semantic one, but a substantial one, if you happen to be a researcher looking for a drug to treat panic disorders.

Finally, although a dispositionalist account of emotions overlooks their social context. How one expresses an emotion like rage will vary considerably according to the company that one is keeping and the nature of the occasion, for instance. One may even refrain from showing one's feelings at all.

We can now re-write the third of our five selected features of animal emotions as follows:

Emotions come in different kinds, and each kind of emotion has a range of intensities, and a generic intentional object. Emotions on specific occasions typically have intentional objects too.

Even with these revisions, our list of the features of animal emotions remains an incomplete characterisation. Although it stipulates that they are mental states, it fails to explain what makes them mental. The only feature it lists which is pertinent to mental states is their intentionality, but as we saw in chapter two, behaviour describable in intentional terms can occur in the absence of mental states. Something more is needed.

In this chapter, I shall endeavour to answer four key questions regarding animal emotions:

(1) What are the cognitive pre-requisites of animal emotions, and what makes them mental events?(2) What are animal emotions "about", and what is each basic kind of animal emotion about? (The problem of intentionality.)

(3) How do we identify basic emotions in animals, and which animals can be said to have them?

(4) In which animals are basic emotions (and other feelings) phenomenally conscious? (The Distribution Question.)

In the following sections, I shall investigate emotions from the standpoint of the two mentalistic intentional stances I identified in chapter two: the agent-centred stance (which will be used to address the first three questions) and the first-person stance (which will be used to answer the question of when feelings can be said to be conscious).