In this chapter, I discuss animal emotions and other feelings such as pain. I deliberately confine myself to "basic" emotions such as fear and anger, whose occurrence in at least some non-human animals is fairly uncontroversial. Thus I ignore emotions such as jealousy, envy and Schadenfreude, which involve high-level cognitive processes. The aim of this chapter is to answer four key questions regarding animal emotions:

(1) What are the cognitive pre-requisites of animal emotions?(2) What are animal emotions "about", and what is each basic kind of animal emotion about? (The problem of intentionality.)

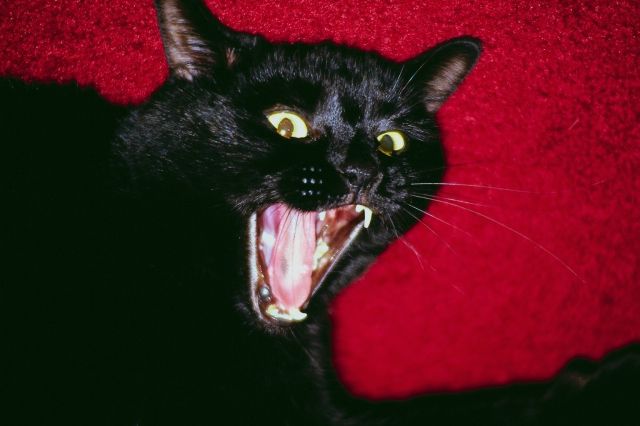

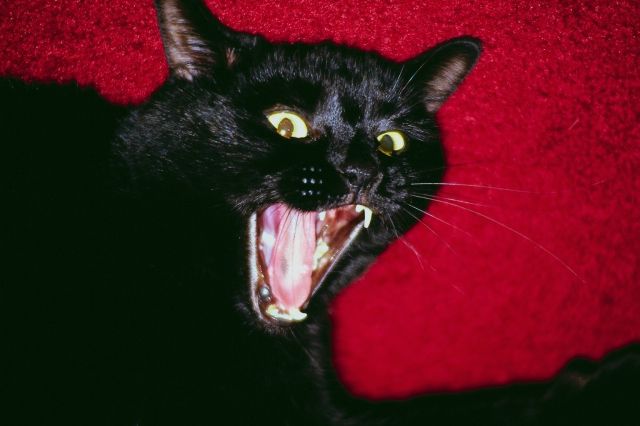

(3) How do we identify basic emotions in animals, and which animals can be said to have them?

(4) In which animals are basic emotions (and other feelings) phenomenally conscious? (The Distribution Question.)

I propose that the reality of emotions in at least some non-human animals should be taken as a methodological "given". I then attempt to identify the distinctive features of animal emotions. The literature on the emotions is vast, so I begin with a representative list of features of human emotions about which a solid consensus exists, and attempt to apply these to animals.

One of these features is that human emotions are typically (if not always) conscious. However, the question of whether phenomenal consciousness is an essential feature of animal emotions sparks debate, not only among philosophers, but even between different scientific disciplines. Within some disciplines, the very concept of an unconscious emotion is an oxymoron, while in others, the notion that consciousness is merely the icing on the cake of emotion (LeDoux, 1998, p. 302) is not uncommon (but see Panksepp, 2003). At the outset, I adopt a broad definition of animal emotions: animal emotions, whether conscious or not, must be mental states which are amenable to scientific investigation. Thus I reject both subjectivist theories, which envisage emotions as essentially private inner states and thereby exclude them from the domain of science, and behaviourist accounts, which define emotions purely in terms of outward behavioural dispositions and thus fail to explain why emotions should be treated as mental states. I address the criteria for animal consciousness later in the chapter, but I allow for the possibility that a large number of animals may have genuine emotions, but live their entire lives at the unconscious or preconscious level. Even if animal emotions are not conscious, however, they must satisfy certain minimum cognitive requirements to qualify as mental states.

Intentionality is another problem I address in this chapter. Emotions typically have intentional objects: they are "about" something. However, some emotions, such as an ill-defined feeling of depression, appear to lack any kind of object whatsoever. Any adequate theory of animal and human emotions must account for both their "aboutness" and their lack of "aboutness". The solution I endorse here is that whereas individual emotions may lack an object, the kind of emotion they instantiate must always be "about" something, which I call the generic intentional object of the emotion. Some authors (de Sousa, 2003) describe the object of each kind of emotion as a formal object which serves as a yardstick for judging the appropriateness of an animal's emotional response on a specific occasion. I argue that for animals that lack language, the only standard for judging the appropriateness of its responses is the animal's own well-being. Accordingly, I envisage the generic intentional object of each kind of emotion not only as a formal object, but also as a teleological object that explains what the emotion is "for" and how it helps the animal to survive and/or flourish.

I address the first of my four questions regarding animal emotions by examining the relationship between emotion and cognition (discussed in chapter two), and conclude from the available neurological and behavioural evidence that although emotions presuppose cognitive states, they are fundamentally distinct from them. Cognitivist and appraisal theories of the emotions, which construe emotions in cognitive terms - e.g. as judgements or evaluations - are therefore inadequate.

If an animal acts intentionally, its behaviour is appropriately explained using the mentalistic agent-centred intentional stance discussed in chapter two: we invoke the animal's relevant beliefs and motivations to account for its actions. In chapter two, we described these motivations as "desires", but other emotions (e.g. fear or anger) are capable of motivating animal agents equally well. If we define an emotion as any internal state that is capable of motivating an animal in intentional agency, it follows that animal emotions, even if unconscious, can be considered as minimal mental states. I propose that the animals to which we can ascribe emotions are simply those whose behaviour is best described in terms of the agent-centred intentional stance.

Because the agent-centred intentional stance presupposes beliefs, emotions can only be identified in animals that are capable of forming beliefs. However, I argue that these beliefs need not be propositional: strategic beliefs (whether conscious or unconscious) about the best way to attain some goal suffice to manifest emotion. The preference beliefs described by Regan, on the other hand, appear to lack the requisite cognitive structure for proper beliefs.

Some philosophers, however, argue that even "basic" emotions such as fear, anger and desire require their possessors to be capable of certain feats that presuppose the use of language. If they are right, then at best, animals that lack language can only be said to have these emotions in an analogical sense, as part of some "attentuated language-game" (Leahy, 1994, p. 136). I argue that on the contrary, there are certain core cognitive requirements for these emotions, which non-human animals can and do satisfy.

I propose that the second and third of my four philosophical questions regarding animal emotions can be resolved by understanding how they are realised within animals' brains. A brain may sound like an unpromising place to look for "aboutness", and I wish to make it clear that I am not espousing any theory which reduces emotions to brain states. My point is rather that the brain embodies the evolutionary history of the emotions, and accounts for their intentionality, at least in generic terms. I make use of Panksepp's (1998) neurophysiological account of animal emotions, according to which the basic emotions in animals arose as different patterns of responding to the various kinds of environmental challenges that their ancestors had to confront. Put simply, the "generic intentional object" of each kind of emotion - what it is "about" - is the environmental challenge it evolved to meet. The brains of human beings and other mammals contain several neurologically distinct, well-described "emotion systems" (Panksepp, 1998), each regulating its own kind of emotional response, which reflect the way in which these animals' brains evolved to respond to these challenges. I claim that the emotion systems in these animals' brains are, generically, "about" the environmental challenges they evolved to meet, in two robust senses. First, the environmental challenges have (over millions of years) caused the evolution of behavioural capacities which are directed at them. Second, each of these emotion systems is capable of motivating intentional acts (which require a mentalistic description), we can say that the environmental challenges have caused the evolution of mental capacities which are directed at them. I contend that rival "feedback" theories of the emotions (LeDoux, 1996; Damasio, 2003) which refine the original James-Lange theory on which they are based, and reduce emotions to internal bodily states, fail to explain the intentionality of the emotions, despite the fruitful scientific research they have generated.

Studies of animals' brains can thus reveal (i) the original motivational context of each kind of emotion, (ii) the "generic intentional object" of each kind of emotion, (iii) the proper taxonomy of the basic animal emotions, (iv) the evolutionary history of these emotions, and hence (v) which animals possess these emotions, at least at an unconscious level. I also formulate criteria for the kind of behaviour which is sufficient for us to identify all of the basic kinds of emotions in animals that have been described by researchers.

Turning to the final problem of how we identify phenomenal consciousness in animals, I contend that most philosophers have been looking for it in the wrong places. Animals' reactions alone cannot unambiguously manifest consciousness on their part, and even intentional agency is not a sufficient condition for its occurrence. However, I argue that a special kind of behaviour by animal agents, namely hedonic behaviour, does require a first-person account. Utility theory allows us to apply first-person concepts to non-human animals (Dawkins, 1994; Berridge, 2001, 2003a, 2003b), but I propose that phenomenal consciousness in animals can be identified unambiguously by affective distortions - by which I mean the kind of emotional mis-judgements that only a creature precoccupied with its own welfare would make. Recent research by Cabanac (1999, 2002, 2004) and Panksepp (1998, 2003) points to ways of measuring these affective distortions.

My specific proposal is that because consciousness can alter human beings' perceptions of risk (Slovic, Finucane, Peters and MacGregor, 2003), it should be possible to identify erratic behaviour in animals blinded by their feelings, which reflects their faulty risk assessments of events in their environment.

The available behavioural evidence suggests very strongly that reptiles, birds and mammals do indeed possess subjective states or phenomenal consciousness. (The case for affective states in other animals is much more problematic.) This finding clashes with the opinion of many neurologists, that even simple consciousness is confined to mammals. However, other neurologists do not share their view, argue that the grounds commonly adduced for this mammalocentric view are inconclusive.

I also suggest that animals' ability to control their emotions - especially fear, anger and desire - (so-called "cortical over-ride") is a sign of consciousness on their part. Research in this area is still in its infancy.

Even if the majority of non-human animals lack phenomenal consciousness, they still matter. To claim that only beings with subjective states are ethically significant is a form of moral myopia. Most unconscious animals still have first-order desires that can be frustrated (Carruthers, 2004). Additionally, they, like other living things, have interests that can be harmed in measurable ways by stressful events.

Finally, I examine Midgley's argument that human beings and companion animals are emotionally symbiotic, and propose that the way in which ordinary people usually identify emotions in human beings is inseparable from the way they identify emotions in animals.