1. What are the cognitive pre-requisites of animal emotions?

In this section, I argue that contrary to cognitivist and appraisal theories of emotion, animal emotions cannot be reduced to cognitive states. I propose that we can identify emotions in animals because of the role they play in intentional agency, even though animal emotions are usually not accompanied by intentional action. Specifically, all animals belonging to species whose behaviour is best described in terms of the agent-centred intentional stance discussed in chapter two - and only those animals - can be said to have emotions. Because the ability to have emotions goes hand in hand with the capacity for intentional agency, emotions can only be ascribed to animals capable of forming relevant beliefs. However, I argue that these beliefs do not have to be propositional.

(a) Is emotion fundamentally distinct from cognition?

Certain influential philosophical theories of emotion characterise emotions using cognitive terminology. For cognitivists, emotions necessarily involve having propositional attitudes towards certain statements. Some cognitivist theories construe emotions as judgements. In appraisal theories, emotions are typically characterised as evaluations.

Regardless of what sort of (conscious or unconscious) cognitions these theories use to characterise emotions, they all collapse in the face of the weighty neurological and behavioural evidence that has been amassed, showing that emotion and cognition are indeed fundamentally distinct.

Neurological arguments for a distinction between emotion and cognition

LeDoux (1998) marshals several lines of argument to the effect that the neural processing for cognitive and emotional reponses is quite distinct, which refutes the view that emotions are either conscious or unconscious cognitions. For example:

Behavioural arguments for a distinction between emotion and cognition

The main behavioural argument for a distinction between emotion and cognition is that cognitive processes, in the absence of emotions, are incapable of motivating animals to act. Aristotle seems to have made essentially the same point in his De Anima 3.10, where he argued that of the two things that seem to cause movement in animals - desire and practical thinking - desire is the crucial factor, as thinking cannot move an animal in the absence of an object of desire.

Damasio (1994) has also documented several case studies in which subjects who had a diminished capacity to experience emotion, owing to injuries sustained in the prefrontal and somatosensory cortices of the brain, were severely hampered in their ability to make intelligent practical decisions.

Similarly, Evans (2001) contends that the vital role of emotions in agency can never be replaced by reason alone. He argues that a race of creatures with a capacity for logic but no emotions, like Dr. Spock in Star Trek, would be non-viable:

It should be clear by now that a creature totally devoid of any emotional capacity would not survive for very long. Lacking fear, the creature might sit around and ponder whether the approaching lion really represented a threat or not... Lack of disgust would allow it to consume faeces and rotting food. And without the capacity for joy and distress, it might never bother doing anything at all - not a good recipe for survival (2001, p. 62).

Conclusion E.1 Animal emotions cannot be reduced to cognitive states such as judgements or evaluations, whether these states be conscious or unconscious. Cognitivist theories and appraisal theories of emotion are therefore inadequate.

(b) The role of emotions in intentional agency

In chapter two, I argued that Dennett's intentional stance could be applied to all mental states, including emotions. However, it turned out that there were two ways of describing the intentionality of mental states: either in terms of the agent's beliefs and desires, or simply as first-person states.

This analysis suggested that an alleged mental state might fail to qualify as such for one of two reasons: it may be possible to adequately describe it in terms of information-states and goals rather than beliefs and desires, or it may be possible to adequately describe it in terms of third-person states rather than first-person states.

For instance, aversive behaviour towards noxious stimuli, which is found in all cellular organisms, including bacteria (taxis), is an insufficient criterion for identifying the occurrence of fear, and similarly, antagonistic behaviour (which occurs in insects) is an insufficient criterion for anger. A goal-centred intentional stance can explain these kinds of behaviour more parsimoniously than a mentalistic account, by appealing to the animal's information-states and goals.

Likewise, since (as we argued in chapter two) learning can take place in the absence of mental states, fear conditioning, or the ability of worms, flies, snails and other animals (LeDoux, 1998, p. 146) to learn to avoid a neutral stimulus which is associated with a noxious stimulus, is an insufficient criterion to establish the occurrence of a mental state such as fear, whether we envisage it as conscious or unconscious.

However, it was also argued in chapter two that while perception, memory, learning and conditioning were not necessarily mental states, certain kinds of learning could only be explained by adopting a mentalistic agent-centred intentional stance: operant conditioning, spatial learning, tool-making and social learning. These kinds of learning are manifestations of intentional agency and presuppose the occurrence of relevant beliefs and motivations. In chapter two, we described these motivations as "desires", but other emotions (e.g. fear or anger) are capable of motivating animal agents equally well.

We now have a criterion for genuine mental states, which emotions satisfy:

Conclusion E.2 Any positive or negative internal state that is capable of motivating intentional agency in a species of animal qualifies as a mental state in that species, and is therefore a genuine emotion (and not a mere behavioural disposition).

One might object that emotions typically accompany reactions rather than actions, and that most emotional reactions in animals are innate and beyond their control. Attempting to identify animal emotions by focusing on intentional agency seems like searching in the wrong place.

However, it needs to be kept in mind that emotions are by definition mental states, and can only be identified when they are manifested in states of affairs which are most appropriately interpreted in terms of mental states. We argued in chapter two that all mental states can be described by Dennett's intentional stance, and that a mentalistic interpretation of an event was warranted if (and only if) it was more scientifically productive to describe the event using either an agent-centred intentional stance or a first-person intentional stance.

Reactions, by definition, cannot be described in terms of an agent-centred intentional stance, as they are not actions. (Nor does it seem that they could require a first-person intentional stance to explain them. Animal reactions are either innate or acquired through conditioning. And as we saw in chapter two, both kinds of reactions can easily be explained by adopting a mind-neutral, third-person intentional stance which employs purely causal terminology.) The only kind of conditioning that requires a mentalistic explanation is operant conditioning, which (as we argued in chapter two) manifests intentional agency. Reactions alone, then, cannot establish the occurrence of mental states such as emotions in animals.

Conclusion E.3 Emotional reactions are bona fide mental states, even in the absence of agency. However, if we want to identify clearcut cases of genuine emotions in animals, then we have to restrict our search to a narrow subset of emotional behaviour and focus solely on intentional agency.

Conclusion E.3 narrows the range of animals to whom we may attribute emotions:

Conclusion E.4 Emotions can only be identified in those species of animals that exhibit intentional agency.

(c) What kind of beliefs do emotions require?

The foregoing conclusions help us to resolve our conflicting intuitions regarding the cognitive requirements for having emotions. On the one hand, it seems obvious that we can have feelings such as fear, even in the absence of beliefs. On the other hand, having an emotion (e.g. fear) seems to presuppose that one has certain beliefs about its intentional object (e.g. that it is frightening).

If we are talking about an animal's emotional reactions, then it is indeed possible that they may occur in the absence of beliefs. Certainly, they will be felt before the animal has had time to form relevant beliefs. LeDoux's example (1998, p. 166) of a hiker who recoils in fear from a thin, curved object in his path, even before his brain has had time to identify the object as a snake, is relevant here. The cognitive processing required to form a belief ("This is a snake") takes time, but in life-and-death situations, emotional reactions in humans and other animals have to be very fast. To make such a decision, the brain relies on crude cognitive processing in the thalamus which identifies the thin, curved object as a possible danger.

By contrast, intentional agency presupposes the existence of beliefs regarding the attainment or avoidance of the object, as we argued in chapter two. The animal forms and revises these beliefs in the process controlling and correcting its bodily movements in an effort to attain its goal. Since emotions can only be identified in animals capable of intentional agency, we may conclude:

Conclusion E.5 Emotions may occur in the absence of belief, but can only be identified in animals that are capable of holding beliefs.

But how should we construe these beliefs?

Emotions are not propositional attitudes

Cognitivist philosophers (e.g. Frey, 1980) have argued that emotions necessarily involve having propositional attitudes towards certain statements: for instance, one cannot be angry with someone without believing that she is guilty of doing something bad.

There are two issues at stake here: first, whether having emotions can be reduced to holding propositional attitudes, and second, whether emotions presuppose these attitudes.

The straightforward identification of emotions with propositional attitudes is fraught with problems (de Sousa, 2003).

First, emotions may run contrary to one's propositional attitudes, as when someone has a fear of flying yet believes it to be the safest means of transport. Thus believing that X is dangerous is neither necessary nor sufficient for experiencing fear of X (de Sousa, 2003).

Second, dispositional beliefs typically have a simple tailor-made form of behavioural expression: someone who believes that P will manifest her belief by publicly assenting to P. Dispositional emotions, by contrast, are much more open-ended, and are capable of being manifested in a diverse range of behaviour.

Conclusion E.6 Having emotions cannot be reduced to holding propositional attitudes.

Emotions do not presuppose propositional attitudes

The view that emotions, while not identical with propositional attitudes, presuppose these attitudes, merits more serious consideration. If it is true, non-human animals are excluded from having emotions at all, as they lack the linguistic sophistication to formulate propositions. Infants and severely cognitively impaired human beings would likewise be excluded.

Regan (1988, p. 42) argues that this conclusion is absurd. He offers the counter-example of an intellectually impaired man who is incapable of learning a language, reacting in terror to the sight of a rubber snake. Our "common sense" intuition is that the man is afraid because he believes the snake is pursuing him and will harm him. If a non-human animal reacted similarly, we would say it was afraid too, and impute the same belief to it. Frey (1980, p. 90) adopts a contrary position, arguing that beliefs (unlike states of affairs) are capable of being true or false. To believe that P is to believe that the sentence "P" is true. Since non-human animals lack language, they cannot formulate propositions and are therefore incapable of having beliefs.

This argument assumes that language is required to distinguish true from false beliefs. It has been argued in chapter two that this is not so: self-correcting behaviour, displayed by animals undergoing operant conditioning, can achieve the same result. If an animal can make mistakes which it then tries to rectify, then it can be said to have beliefs about its goals. Intentional agency is the critical factor, not language.

Let us modify Regan's case a little, and suppose that the snake is not a rubber snake but a very life-like mechanical toy with a built-in thermal sensor, programmed to pursue the nearest warm object. Several people and one animal are in a locked room with the snake. The animal is standing nearest to the snake. Startled, it initially backs away but is pursued by the snake. If the animal proves capable of adjusting its strategy for avoiding the snake, by learning to position itself behind someone in the room when approached, then we can justifiably say that the animal believes that the snake will pursue (and harm) that person rather than itself. The attribution to the animal of the mental state we call fear would then be warranted, as the animal is using the content of its beliefs to avoid the snake.

But what should we say about an animal which is incapable of engaging in self-correcting behaviour, in any situation? What if it reacts to emotional stimuli, but is incapable of modifying its actions to pursue or avoid these stimuli? In that case, we would have no warrant for ascribing agency to the animal, and hence no grounds for ascribing emotions to it (according to Conclusion E.4). As we argued above, reactions alone cannot supply such a warrant.

We can now formulate the following conclusions:

Conclusion E.7 The attribution an emotion to an animal does not require it to have propositional attitudes.

Conclusion E.8 The attribution an emotion to an animal requires it to be capable of self-correcting behaviour that enables it to modify its strategies for attaining its goals.

In other words, propositional attitudes are not necessary. Strategic attitudes - "This works; that doesn't" - are what counts. That being so, there is no compelling reason why we should be reluctant to ascribe emotions to animals - even if specific emotions, such as remorse, presuppose linguistic abilities beyond the reach of non-human animals.

The propositional content of beliefs that accompany emotions

Even if emotions do not presuppose propositional attitudes, it could be argued that they must have some propositional content. However, this would entail the absurd consequence that the hiker described by LeDoux (1998, p. 166), who recoils from a thin, curved object in his path, even before his brain has had time to identify the object, does not experience the emotion of fear, as his emotion has no specific content until the visual cortex of his brain identifies the object as a snake.

On the other hand, any beliefs which accompany a particular emotion must surely have a propositional content - otherwise, they could not be described as beliefs. But what might this content be?

First, the animal has to be capable of forming strategic beliefs whose content relates to how it can pursue or avoid the intentional object of the emotion, as occurs in operant conditioning.

Second, the animal may be said to implicitly believe any propositions whose content is entailed by the strategic beliefs it forms. Returning to the case cited above, an animal that entertains the strategic belief that it can avoid a snake by positioning itself behind one of the people in the room, also implicitly believes that:

(a) there is a snake in the room;

(b) the snake needs to be avoided;

(c) there are people in the room; and

(d) it is not presently positioned behind any of them.

If my proposals regarding animal beliefs are correct, then an animal can only be said to have emotions directed at intentional objects if it is capable of forming beliefs about strategies for attaining or avoiding those objects. This implies that if an animal desires X as an end in itself, it must also be capable of believing that Y is a means to X, and consequently desiring Y.

Conclusion E.9 Any animal that is capable of desiring ends (e.g. food or sex) must also be capable of desiring means to these ends.

I would thus agree with Frey (1980, p. 104) in rejecting the possibility of an animal that only has simple desires, such as a dog's desire for a bone. Nor can I accept Regan's proposal (1988, p. 58) that a dog which desires a bone also has a preference-belief that there is a connection between its choosing a bone and satisfying its desire for a certain flavour. First, it is doubtful whether dogs can desire such abstract things as "flavours"; in Regan's example, the appropriate object of the dog's desire is surely the bone itself. Second, there is no genuine means-end behaviour in this case, as there is only one action (choosing the bone) and one physical object (the bone), with no manipulation. Finally, one can construct parallel examples with organisms lacking desires. Should we say that a bacterium chooses a glucose-rich solution as a means of satisfying its desire for sweetness? By contrast, Regan's example (1988, p. 70) of the dog digging in the garden to retrieve an old bone it has buried is a perfect illustration of the kind of behaviour that manifests a strategic belief. No bacterium could do that.

Although I agree with Frey's rejection of simple desires, I part company with him on the question of whether an animal's behaviour alone can manifest the beliefs it must be capable of entertaining, before it can be credited with desiring those ends. The examples cited by Frey to establish the inherent ambiguity of animal behaviour - notably the case of his dog, which wagged its tail in the same way when its master was outside the door, when lunch was imminent and when the sun was ecliped by the moon - are not good ones, as they do not include the kind of strategic behaviour discussed above.

(d) Do the basic emotions of fear, anger and desire presuppose a capacity for language?

Before we conclude our discussion of the identification of basic emotions in animals, we have to address arguments purporting to show that these emotions presuppose feats of rationality and language that non-human animals are incapable of. I argue that on the contrary, non-human animals can and do satisfy the core cognitive requirements for these emotions, without requiring language.

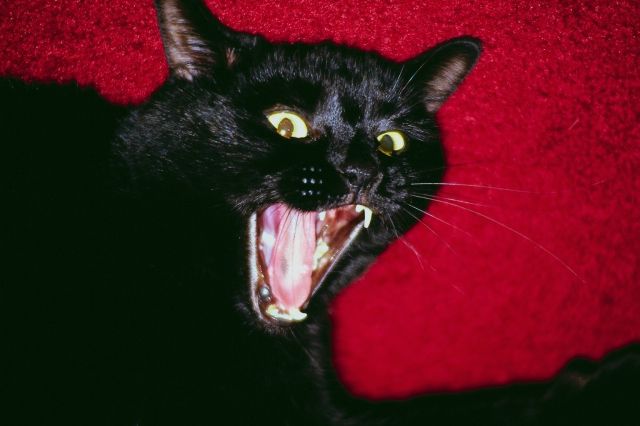

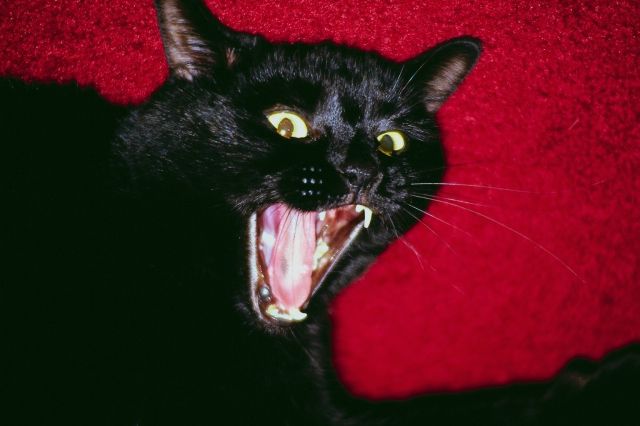

Cognitive requirements of fear

It has been argued that fear, in the fully-fledged sense of the word, has to be amenable to reason.

Leahy (1994, p. 136) claims that when we ascribe fear to animals and to rational human beings, we are playing two distinct language games: human fear is amenable to reason whereas animal fear is not. People can be argued out of their fears if they can be shown to be groundless, but animals cannot. The object of an animal's fear operates not as a reason for its behaviour, but rather as a cause of its behaviour (1994, p. 135). Indeed, Leahy considers the dissimilarities between animal and human fear to be so profound that one could justifiably use two distinct words to differentiate them. In the end, he decides to use one verb to describe both cases, but only because the similarities in the overt behaviour of frightened people and animals are so profound.

I have several comments to make in response to Leahy's claims. First, it would be grossly mistaken to view the similarities between human and animal fear as merely behavioural, as Leahy seems to do (1994, pp. 135-136). Animal fear cannot be cashed out in dispositionalist terminology which describes external behaviour. The fact that scientists routinely perform research on animals to discover the causes of and treatments for fear in humans (LeDoux, 1998; Hall, 1999) would make no sense unless the internal neurological and affective states accompanying fear were substantially the same in humans and other animals.

Second, when contrasting human fears with those in other animals, it is essential to compare like cases. Once we do so, we find that fear, properly speaking, is amenable to reasoning in humans only under restricted circumstances. The inability of other animals to reason their way out of their fears then becomes far less anomalous.

There is a growing consensus among psychiatrists (see Catherall, 2003, pp. 76-78) that there is a significant difference between fear and anxiety in both humans and animals: fear is a response to a present danger (e.g. a predator) that is triggered by perceptions (e.g. the sight of a lion), while anxiety (or worrying) is a response to potential threats that involves cognitions rather than perceptions. The point is that because fear, unlike anxiety, is processed within the brain independently of higher-level cognition, fear behaviour is typically involuntary, even in human beings.

Behavioural responses to innate fears, such as the fear of a predator, are involuntary in humans as well as non-human animals. These fears have evolved in response to stimuli that consistently threatened our survival during evolutionary history (Panksepp, 1998, p. 207). These innate fears are tailor-made to circumvent the need for reason and other cognitive inputs, in both humans and animals. In LeDoux's (1998, p. 166) earlier example of a hiker in the woods who abruptly encounters a long thin object in his path and jumps clear, - even before the visual cortex in his brain has had time to ascertain that it is indeed a snake and not a stick, - the ability to respond rapidly may make the difference between life and death.

Conditioned fears in humans and other animals are also largely involuntary, because fear memories are stored in the brain's amygdala, from which they can never be erased (LeDoux, 1998, p. 146; Hall, 1999). There is a good evolutionary reason for this: the brain's ability to recall stimuli associated with danger in the past assisted individuals' survival (LeDoux, 1998, p. 146). According to LeDoux (1998), the only way to eradicate a fear acquired through conditioning) in non-rational animals, is to repeatedly expose the animal to the conditioned stimulus in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus. The same approach is used in the first phase of treatment for humans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (Catherall, 2003, pp. 84-87). Eventually, this leads to "extinction" of the fear response. In reality, however, the fear is merely dormant, and may be re-awakened simply by exposure to some stressful or traumatic event (LeDoux, 1998, p. 145). Conditioned fears prove to be equally indelible in people who develop phobias. Phobias show only limited "amenability to reason": psychotherapy allows the fear of the phobic stimulus to be kept under control for several years, but after some stress or trauma, the fear returns in full force, just as it does in animals. Therapy, like extinction, cannot erase the memory (LeDoux, 1998, p. 146). The differences here between humans and other animals hardly deserve to be called a new "language game".

The study of fear disorders in human beings sheds further light on why they are not amenable to reason. Catherall (2003) points out that while anxiety disorders can be treated on a cognitive level (as in insight therapy), fear disorders cannot, because exposure to a traumatic stimulus triggers changes in the brain which prevent reasoning and language processing. PET scans show that in a subject exposed to a traumatic stimulus (e.g. a snake), the speech area of the brain (Broca's area) may be deactivated, making it impossible for the subject to access his explicit or declarative memory and deal with the fearful stimulus by recalling facts ("It's a green tree python, so it can't poison me") that would alleviate his fear. This kind of cognitive processing is only possible while the individual's fear state remains below a certain threshold (Catherall, 2003, pp. 79-80).

Thus Leahy's contention (1994, p. 137) that people (unlike animals) can be argued out of their fears if they can be shown to be groundless, is true of anxiety rather than fear as a whole. Only low-level human fears are "amenable to reasons" (Leahy, 1994, p. 135).

It should not be thought that fear behaviour in non-human animals is totally inflexible. In fact, we find a suite of adaptive behaviours to fear in animals. First, animals can lose their fear of an object through a process of habituation.

Second, animals lose their fear of an object if a change in perception reveals that it was not the danger they thought it to be.

Third, animals living in hierarchical societies are capable of learning from experience, that they need no longer fear formerly dominant conspecifics that lose status.

Fourth, juvenile animals can learn specific skills for avoiding things they fear - such as predators.

Is there, then, any minimum level of adaptability that we should expect in an animal capable of intentional agency, which is undergoing the emotion of fear? Habituation does not seem particularly impressive: as we saw in chapter two, it is not one of the behavioural conditions for intentional agency. By contrast, an animal's ability to use incoming sensory data to self-correct its behaviour is an integral part of the mechanism of intentional agency, be it operant conditioning, spatial navigation, tool use or social learning (see DF. 1 to DF. 4), and should therefore feature in even a minimal definition of fear as a mental state:

Conclusion E.10 Before it can be credited with fear at its lowest cognitive level, an animal must not only be capable of intentional acts enabling it to avoid some dangerous stimulus, but also be capable of adjusting its behaviour when new sensory data reveal the stimulus to be harmless.

Regan (1988, p. 42) cites the case of a deranged man, bereft of reason, who shows signs of terror and jumps back when confronted by a rubber snake, apparently trying to avoid it. Is he really afraid? We cannot alter the man's behaviour by telling him that the snake is not real, but we can still change his perception - either by removing the rubber snake or by chopping it into pieces. If the man then calms down, then we can say he was afraid.

It is certainly true that humans have a unique capacity to control their fears - even innate ones. Most of us have sufficient control over our fear of snakes that we can pick up a green tree python, which we know to be harmless, and a few individuals can even conquer their fears enough to handle poisonous snakes. But what these examples show is the uniqueness of human cognition, rather than human emotion, as we re-define what is and is not dangerous ("That green snake won't hurt you; it's harmless.") Humans, unlike other animals, are capable of modifying their behaviour on the basis of information conveyed through the medium of language: we have been taught that despite appearances, green tree pythons will not hurt us, and even cobras can be handled safely. A non-human animal knows that snakes are dangerous, but because it lacks language, it cannot explain precisely why they are, and thus it is incapable of understanding why its innate fear response to green tree pythons is inappropriate.

Language also allows human beings to rationalise stimuli that might otherwise frighten them. According to Grandin (1997), prey animals (including horses and cattle) have an innate tendency to acquire fears of things that look out of place (even a piece of paper blowing in the wind), sudden movements (which resemble the movements of predators) and high-pitched noises. But even though these animals cannot tell themselves that there's nothing to be afraid of, there is no reason to doubt the reality of their fear.

Cognitive requirements of anger

The difficulty in ascribing anger to animals arises from the advanced mental states that anger appears to require. Thus Aristotle defined anger as "a longing, accompanied by pain, for a real or apparent revenge for a real or apparent slight... when such a slight is undeserved" (1959, The Art of Rhetoric, 1378a, J. H. Freese (tr.), London: William Heinemann). Leahy (1994, p. 80) argues that these cognitive requirements are beyond the competence of non-human animals, and that it is only their enraged behaviour that resembles that of angry human beings.

Two comments are pertinent here. First, instead of saying that only undeserved slights can elicit anger, it would be better to say that the knowledge that a slight is deserved can reduce (and perhaps obviate) anger. Of course, most animals, like very young human infants, lack the concept of "just deserts", so their feelings of rage cannot be assuaged in this way.

Second, Aristotle's definition of anger is too narrow: he focuses on "slights", or insults, but in human life, one may feel anger at another individual for a variety of reasons: a slight, an action that gave offence without being intended to do so, some sensory irritation ("He has terrible body odour") or a physical obstruction ("I wish he'd get out of my way").

Third, we can speak of various "cognitive grades" of anger. A human longing for revenge against a mortal enemy is obviously of a much higher grade than the momentary surge of anger an infant may feel towards an "offending" individual who is thwarting her wishes (e.g. by denying her something she wants), but I would argue that if the infant attempts to strike back at the individual, acting on certain strategic beliefs about appropriate ways of doing so (e.g. "Pushing didn't work? OK, try punching or kicking"), then her behaviour qualifies as intentional agency and hence bona fide anger of a low-level variety: rage. I propose the following tentative conclusion:

Conclusion E.11 In order to be capable of anger at its lowest cognitive level, an animal must be capable of intentional acts directed against some offending object, individual or bodily irritation, which are accompanied by certain strategic beliefs about an appropriate way to strike at the offending stimulus.

This ability is likely to be found in all vertebrates, as well as many insects and cephalopods.

We could define a higher grade of anger as the desire to strike out at an offending individual. The cognitive requirements of anger are likely to be satisfied by many species of vertebrates and possibly even insects. The desire to strike out at an offending individual requires nothing more than (a) an ability to recognise other individuals and (b) an ability for "book-keeping", or keeping track of other individuals' behaviour during past interactions. The former ability has been documented even in wasps (Tibbetts, 2001) and is widespread across fish families (Bshary, Wickler and Fricke, 2001). The latter ability has been identified in at least two kinds of fish - sticklebacks and guppies are capable of "book-keeping" with several partners simultaneously, and there is tentative evidence that they tend to adopt a "tit-for-tat" strategy in their dealings with one another: a player starts co-operatively and does in all further rounds what his/her partner did in the previous round (Bshary, Wickler and Fricke, 2001). Non-human primates are renowned for their ability to keep track of their own and others' misdeeds over a longer period, as described by van der Waal in his book "Good Natured" (1996).

Cognitive requirements of desire

Frey (1980) offers an ingenious argument against the occurrence of desires in animals. He considers the straightforward case of a dog that desires a bone. "Suppose", he argues, "my dog simply desires the bone: is it aware that it has this simple desire? It is either not so aware or it is" (1980, p. 104). He then argues against both possibilities. If the dog is unaware of its simple desires, then it has unconscious desires. While it might make sense to say that some of a creature's desires are unconscious, it makes no sense to say that all of them are, for then the creature's conduct would be no different from that of a creature with no desires at all.

If one the other hand, the dog is aware of its desires, then we have to answer the epistemological question: how do we know that it is aware of them? Nothing in the dog's behaviour could tell us this.

However, Frey's argument hinges on the questionable assumption that to have a conscious desire, one must be aware of one's desire. An alternative position (Lurz, 2003) is that to have a conscious desire, one must simply be aware of its object. What this awareness might consist in will be discussed below.

Additionally, there may be ways of ascertaining whether a dog is aware of its desires. For instance, I argue below that the phenomenon of hedonic behaviour suggests an awareness in an animal of its internal affective states.

Conclusion E.12 The basic emotions of fear, anger and desire do not presuppose the use of language.