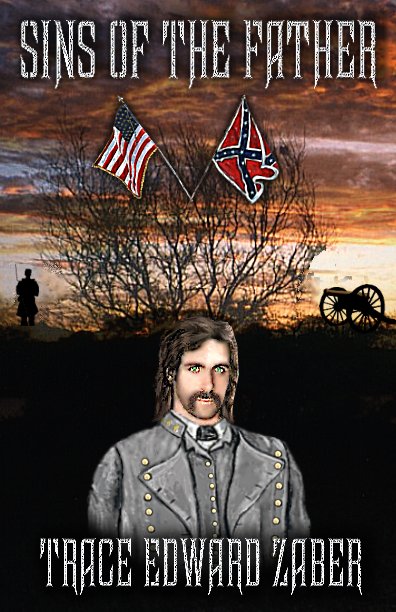

© Cover Copyright 2000, Trace Edward Zaber ISBN: 1-59279-016-X

So this is war. Faith Bradshaw pondered those words as the wagon jostled southeast along the rutted Mummasburg Road toward Gettysburg. War certainly wasn’t glorious or dignified as many politicians would have one believe. It certainly wasn’t the grand and marvelous spectacle described in books of yore. She had often speculated just how reality and patriotic fiction differed. Until now, she had considered herself and her town fortunate for not having experienced a battle, unlike scores of Southern communities. Indeed, the only near encounter had occurred during last year’s battle at Sharpsburg, Maryland, some forty miles distant. Yet forty miles made all the difference between fiction and fact. Still, she had presumed the reality would be bad. But she had never expected such a nightmare of bloodshed and death, had never envisioned this peaceful town as a charnel house, a butcher’s pen with man as its victim. Now her hometown served as a haven for thousands of wounded, a burial place for thousands more, mutating this once beautiful countryside into a replica of hell. No written accounts, no photographic evidence, regardless how advanced the art had become, would ever do the reality justice. Faith massaged her temples. Even the snood enclosing her waist-length, bronze-colored hair seemed burdening. She felt older than her twenty-one years, assumed she looked older as well. After three seemingly-endless days of battle, she knew her blue eyes were puffy from tears, fright, and lack of rest. Not being able to sleep was the worst of it, but a good night’s rest to relieve reality’s strain was a luxury, one she wouldn’t receive anytime soon. Black clouds shrouded the western sky over Seminary Ridge. Thunder rippled the Saturday afternoon air. Despite her aversion to thunderstorms, Faith breathed easier nonetheless, for at first she’d feared the reports of a cease-fire had been erroneous. The teamster, a muscular Negro with a face so dark it exhibited a blue cast, patted her hand. “It’s all right,” he said in his sonorous voice. “They’re gone, let’s pray for good.” “Amen. Thank you, Isaiah.” “You try to put up a brave front, yet I can see your skittishness. But now it’s over.” The battle perhaps, but not its aftermath, Faith thought, giving his work roughened hand a fierce squeeze. When Isaiah announced plans to take the wagon into town for supplies, she had jumped at the chance to accompany him, disregarding his warnings about the area’s condition. Anything to free herself from the house. Listening to the suffering of the wounded was bad enough, but living without a break from the stench would have forced her brother, Steven, to commit her to an asylum. Yet that might not be such a bad alternative, not after this. In all directions, canteens, muskets, and ramrods littered the fields. Clothing speckled the landscape in tones of blue, gray, and butternut. Shreds of envelopes and letters danced among shoes, rubber blankets, and pocket testaments. Crocks of butter and lard rotted away in the sticky heat beside candlesticks, bonnets, even a feather mattress, obviously pilfered from homes with the intention of resupplying an impoverished South. Fields, once healthy and bountiful, lay charred or ground to a jelly. Trees, raked of leaves, chopped to the bark by musket balls, stood at drunken angles. Chickens, hogs, and oxen lay moldering, while their wounded counterparts raised an occasional plea for someone to end their misery. Scattered amongst broken gun carriages, dead horses abounded; in defiance of Newton’s ancient law, their uppermost hind legs, swollen in decay, hovered inches above the ground. One creature hung halfway over a fence, as if shot in mid leap. A sea of wounded men commanded the expansive lawn of Pennsylvania College. Stretcher-bearers marched hither and thither, hauling patients into the main building. Bloodstained textbooks, which had served as pillows, cluttered the grass, their pages flapping in the breeze as if being perused by phantom students. But the worst hell—the bodies. Lifeless forms lined the fields, waiting with eternal patience for someone to inter them in shallow trenches. The riotous movement of flies and maggots seemed to bring their sun-blackened faces alive. Bloated hands clutched tufts of grass, medals, or daguerreotypes. Adversaries lay together in mocking camaraderie. As hundreds of glaring, unfocussed eyes stared a constant vigil, Faith’s stomach churned. No, she pondered, never in her wildest fancies could she have envisioned such a nightmare. The wind quickened, thrusting malodorous air into her face. She coughed as her lungs rejected the poisonous miasma. She fumbled in her pocket for a bottle of pennyroyal. Soon a minty smell temporarily squelched the odor of rotting flesh. “You were right about the area’s condition, Isaiah.” “Do you want me to turn back?” She lifted her chin. “Supplies are needed and, by God, supplies we will collect.” “You’re a determined young lady. That’s your mother’s influence coming through.” “I just thank the Lord she’s not here to see the ruination of her homeland.” But Faith also knew Gillian Bradshaw would have persevered. Before she had succumbed to cancer nearly eleven years earlier, Gillian spent the first ten years of Faith’s life instilling strength in her youngest child. Faith knew she’d inherited her mother’s feistiness, her tenacity to see things through. She just prayed her mother’s lessons would aid her now when she needed them most. Her fingers traced the cameo brooch at her collar. Her mother’s brooch provided inspiration, reminded her of lessons embedded long ago. “We didn’t request to have our lives turned topsy-turvy. But Providence has assigned to me a sacred duty, and I mean to accomplish it.” A crack of thunder rocked the earth. Its striking resemblance to booming cannon pruned away some of her resolve, but she clutched the brooch, battling to regain her strength. “You all right?” asked Isaiah. Faith smiled at the thirty-year-old man who had come into their lives just before her mother’s death. Without a surname, but with his former master’s written permission and his own dogged resolution, Isaiah had trudged hundreds of miles into northern territory, searching for a better life. In Cincinnati, he’d met Faith’s father at an abolitionist rally. Nathan Bradshaw immediately took a liking to the bright-eyed youth with a gentle nature and an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and offered him both a job and an education. So moved by the young man’s will to foot it all the way into the north, Nathan had even suggested the man’s adopted surname. Ever since, Isaiah Walker had become an indispensable member of the family. “I’m all right now, Isaiah, knowing you’re safe.” Isaiah and some of the town’s other Free Blacks had hidden themselves in the belfry of Christ Lutheran Church after narrowly avoiding Confederates determined to reenslave them. “I can’t help thinking that if Father had been here, perhaps you might not have gone through—” “What could he have done? Besides, he’s in Europe doing righteous work for my people. That’s more important than saving my lone hide.” “Father’s a world-renowned abolitionist, for glory’s sake, working with Frederick Douglass. He has the ear of many important men in Washington.” “That don’t hold no truck with the Rebs. After all he’s done for me, I wouldn’t want to see him hurt trying to defend me to a pack of ornery Graybacks.” A bolt of lightning sliced the western sky. Thunder rumbled. Faith’s gaze settled on a bullet-stormed tree; a severed arm dangled from a branch. She closed her eyes, fought the urge to retch, and clutched the cameo. “Stop that!” shouted Isaiah to a man in a field, who was creeping among the dead, carrying a bulging burlap sack in one hand and a knife in the other. With the blade, the man made an obscene gesture before turning back to his macabre business. “What was he doing, Isaiah?” “Cutting off a finger just so he can claim possession of the ring.” Instantly, anger replaced Faith’s shock. “First they suffer the indignity of awaiting burial, then they’re robbed in such a devilish fashion. What pushes people to cold-hearted acts?” “Takes all kinds to make up this world.” Isaiah pointed. Many such men roamed the fields in their quest for resalable goods, leaving behind shoeless corpses with out-turned pockets. “Ghoulish scavengers, blind to the slaughter. All they see is the possibility to turn a profit.” Faith’s blood began to boil. “I almost wish every man, woman, and child could witness this, then they’d truly appreciate the horrible price paid by their countrymen. They wouldn’t be so quick to call fervently for war in future. It amazes me how this country is so quick to boast of its compromising nature, yet the failure to compromise, this bigoted obstinacy is what started this. If the hotspurs who goaded the country to choose sides could witness this, perhaps both sides would sue for peace come the morrow.” “I reckon that’s true.” Storm clouds swallowed the noontime sun. Drizzle began to fall just as Isaiah directed the horses onto Carlisle Street, taking them past the railroad station into the northern end of town. Shrieks poured from the three-story Washington House Hotel, its rooms accommodating the wounded. Cries emanating from McConaughy’s Hall, a large warehouse, told of the building’s similar fate. All around, stretcher-bearers scooped up the wounded from beds of hay on the sidewalks, while other men nailed signs above various doorways advertising embalming facilities. Civilians were uprighting fence rails, collecting window glass from flower beds, washing blood from walkways, even counting in dumbfounded consternation the number of bullet holes in their honeycombed walls. Though the sights were loathsome, Faith felt a strengthened kinship with the townspeople, for these were the very tasks she’d also performed. The wagon crept into the Diamond, the center of Gettysburg’s business district. Between speeding supply wagons, adolescents scurried with water buckets, their faces displaying expressions from boyish excitement to adult trepidation. Sightseers stood before the Tyson Brothers Gallery, scanning the damage inflicted on the photography studio by an unexploded shell. Looters burst from the Arnold Building, their arms freighted with pilfered clothing, while others wrenched bullet-spattered shutters from the windows of Boyer’s Grocery to use as kindling. Clusters of blue-clad soldiers passed around liquor bottles; some spewed proud boasts of valor; others spat wads of tobacco into puddles of God-knew-what. Matterhorns of coffins littered the sidewalks. Curses, moans, and military orders clogged the air, punctuated by the intermittent cracks of rifles. A private on horseback waved them to a stop. In swift obedience, Isaiah braked the wagon. “Where are you heading?” asked the soldier. “To Fahnestock’s store,” replied Faith. She held out her arm, bearing a white cloth tied around her sleeve just above the elbow. “Hospital folk? Not there, Miss.” “I was told the Sanitary Commission would be using Fahnestock’s.” “They can’t get through. The blasted Secesh blew up the Rock Creek Bridge days ago.” “Then where are the supplies?” “The White Run Schoolhouse.” Faith tensed. The schoolhouse was some distance south of town along the Baltimore Pike, not far from where the heaviest fighting was rumored to have occurred. Who knew what dangers she’d have to face? She gripped the cameo at her throat. Isaiah began to jiggle the reins, but the soldier halted him. “Can’t let you go that way.” With his pistol, he pointed to the western end of the Diamond, down Chambersburg Street. Faith saw Christ Lutheran Church, its high-stone steps overlaid with wounded men. There, also, stood barricades of wood, stone, and sundered wagons. Behind the prepared obstruction, soldiers crouched with guns outstretched, facing westward. “Reb sharpshooters took over Haupt’s Hill,” explained the soldier. “They’re picking off anything that moves to cover their retreat. You have to turn ’round. Go through that alley to Stratton, then head south.” Faith felt the blood drain from her face and knew Isaiah and the soldier could see her mounting terror. “Don’t worry,” said Isaiah, “we’ll get there.” He whipped the reins, setting the horses in motion. “Damned Rebels!” Wind blustered through the ruined streets; tapping drizzle amplified into a bludgeoning rain. Faith seized a cape from the wagon bed, wrapped it around her shoulders and pulled up the hood as Isaiah directed the wagon on the suggested route. Agape, Faith silently eyed the town’s changes. At Stratton and East High Streets, a parade of stretcher-bearers entered the German Reformed Church; the half-century-old building brimmed with wounded, while a red flag fluttered from its cupola, signifying its use as a hospital. On East High Street, they passed the turreted Adams County Prison, its spike-fenced yard clogged with sodden Confederate prisoners. The Union Public School, with a wind-lashed crimson flag flying above the entrance, also acted as a haven for the wounded. Soon, the wagon turned south on Baltimore Street. Faith continued to clutch the cameo, determined to sustain her stoicism, but as signs of devastation increased, she found the task ever more difficult. Just past Breckenridge, a girl emerged from a house. Faith called a word of greeting to her childhood friend, Anna Garlach. Anna hastened to meet the wagon. “You’re safe, thank God.” Faith nodded. “And your family?” “All in good health. Where are you heading?” “The White Run Schoolhouse, for supplies.” “Mother’s there now. She’s been helping at the courthouse and other makeshift hospitals. You as well?” “We have one of our own.” Anna’s jaw plummeted. “Not in your house?” “Ever since the thing began.” “But you’re north of town”—she gasped—“in former Rebel-held territory.” “Our house is a Confederate hospital.” “How can you stand it? They’re nothing but uneducated vermin.” Who bleed and die like everyone else, Faith thought, but she held her tongue as a bundle of barefoot Confederates trudged north along the muddy street. A half dozen Union soldiers encircled them, urging them forward with the occasional poke with a musket. Rain slapped the ground, yet the captives seemed not to notice. In gentlemanly fashion, they tipped their hats at the women. Though Faith didn’t acknowledge their greeting, she had to admit just about every Confederate she’d met since the battle had been most polite. And her surprise at that revelation lent a guilty twinge. Earlier, she’d declared that bigoted obstinacy had sparked the war. Though she’d never thought herself a bigot, she certainly felt like one now. The Rebs weren’t the tempestuous ruffians and ill-mannered buffoons political propaganda had led her to believe. Indeed, after witnessing many Rebels dying under her roof, her heart broke for them as it would for any of their Northern counterparts. She frowned. Another bigoted notion dashed. “Hope you Cotton Rebels rot in Hades,” Anna snapped at the prisoners. When one man winked, the young girl stomped her foot. “Honestly! First they traipse from Cottondom to invade our town, then have the audacity to flirt like dandies. As if any of those hooligans could hope to become suitable beaux. Papa would have a regular conniption.” Isaiah cleared his throat. “Shouldn’t we get moving before the storm picks up?” “You’re absolutely correct.” Faith turned to Anna and wished her and her family well. The girl, still using her eyes to thrust scornful daggers at the passing captives, didn’t seem to hear. As the wagon bounced past the increasing signs of death and destruction, Faith fingered her cameo, praying she’d be able to maintain her resolve, and wondering if the hatred and bigotry would ever end.

The heavens spat rain in a torrential downpour, slapping General Jebediah Ellsworth from uneasy slumber. Thunder rocked the earth; the ground quivered in reply. The first thing Jeb felt was the ache in his stomach, not from hunger pangs that had intermittently plagued him for months, but from the gut-churning stench. Then came the agony along his entire left side; each well-aimed raindrop felt like acid pelting his wounds. When he opened his eyes, his left eyelid refused to budge. He groaned and for an instant wondered if his body hadn’t been used as a razor strop by some fiendish giant of a barber. But then the memories returned, bringing with them a mixture of panic, horror, and distress. The damned charge! Dear God, where are my brave boys? He turned his head. On his left lay a dead horse, its three remaining legs stretching in Jeb’s direction. Worms and green bottleflies, feeding on the decaying flesh, swarmed over the hole where the fourth limb had been. Jeb turned his head back to the gray-clad sky, waiting for the fresh bout of queasiness to pass. Eventually, he looked to his right, finding near him the lifeless body of a comrade. Unrecognizable in his bloated condition, the soldier faced the sky with forearms bent back on stiff elbows, as if pointing an accusatory finger at heaven. The disheveled uniform gave the appearance of looting, but Jeb knew the man had done it himself; men shot below the chest usually tore at their uniforms, frantically searching for their wound, knowing a hit in the gut would preface a swift death courtesy of stomach-lacerating minié balls. When he tried to move, pain clenched his jaw, yet he mustered strength to inspect his torso. Intact, no signs of self-ransacking, just blood on the left side of his jacket. He released a thankful sigh, then lifted his right arm. He held it before his good eye and smiled. It remained. Scathing pain, however, darted through him when he tried to move his left arm. Renewed dread hammered into his brain. With his right arm, he reached over his body, felt with his hand. His left arm, it was there. His right hand traced its outline, moved up its length under the blood-soaked jacket to the shoulder. Still attached. But for how long? If his bone was shattered, his muscles shredded, no alternative to amputation existed. Fear quickened his heartbeat; images of surgeons’ blades flashed through his mind. He tried to marshal his courage. Jebediah, you’re a brave officer, calm yourself. Then, with a prayer, he attempted to move the fingers of his left hand. Nothing but horrific agony. A lump came to his throat. He tried again. Please God. Then again. Please. Movement. Faint. But movement, nonetheless. Relief rushed over him. Agony in his left leg and ankle indicated additional wounds, but their biting pain had dulled to a steady throb. Another faint smile haunted his cracked lips. “Pain’s acceptable,” he mumbled to his deceased comrade, “because it makes me alive.” The condition of the soldier’s body told Jeb a day or two must have passed. Despite the downpour, nebulous shapes of hawks and buzzards circled overhead. Jeb could almost sense their anticipation as they surveyed the banquet of flesh below. Now what am I to do, Father? he thought. Monumental depression, a keening, unbearable sense of loneliness and grief filled his soul. He wanted his father. His mentor. Needed to see him. Hear him. Touch him. But his father was gone forever, killed in battle, shot from his horse while defending the cause. Tears blurred the malevolent sky. “Why was I spared, Father? Why—” Voices interrupted Jeb’s lament. He pushed his own voice to cry out, but no strength remained in his throat. With all his might, he concentrated on his uninjured arm. In dreamlike slowness, it elevated and stood erect over him. “Help.” Gravity yanked and tugged. His arm muscles ached, but he fought the earth’s pull. “God...water...someone...” A female voice pierced the stillness of the battlefield. “Over here! Dear Lord! He’s alive!” “Thank you, Father,” muttered Jeb to the heavens. “I knew I could count on you.”

As the wagon lurched down Emmitsburg Road, every rock uncovered by the springless wheels sent a fresh wave of pain through Jeb’s body. He tried to focus on anything other than the physical agony, but the horrific sights were just as hard to endure. The mile-long field stretched before him. He imagined he could walk for yards across fallen Confederates and his feet would never have to touch the ground. Secesh currency floated in muddy pools of rainwater. Jewelry sparkled in boot trampled grass. Jettisoned card decks and homemade dice, flasks and bottles, licentious dime novels and risqué daguerreotypes dotted the land, the signs of soldiers ridding themselves of objectionable belongings as death approached. Men toiled on burial detail. Flesh slithered off the mangled corpses, making the job all the harder. Men with pike poles rolled corpses onto stretchers, while the stretcher-bearers gagged. Some bodies had exploded under the force of death’s gasses, while others possessed fist-sized water blisters. Boys shooed away hogs that had beaten the hawks and buzzards to the gruesome feast. Gravediggers with kerchief-masked faces looked like bandits as they searched corpses for identification. Others fashioned grave markers out of roofing shingles. Some stood beside freshly-dug trenches, hats over hearts, respect for death blinding them to colors of blue and gray. Elsewhere, citizens tossed fence rails around mountains of dead horses. With kerosene-drenched wood, they set the stiffened animals ablaze. The wagon passed one such hellish bonfire and the nauseating aroma of a country barbecue and rotting horse flesh filled Jeb’s nostrils. When the wagon rattled into the southern edge of town, the ancient teamster hailed a group of women. “Another live one, Miss Garlach. Any idea where to take him?” The young woman wiped sweat from her forehead. For a moment, she viewed Jeb with brutal eyes, then turned. “Where to, Mama?” The matron neared the wagon, wisps of hair escaping her snood. “Who are you?” she asked Jeb, fishing paper from her pocket. “Can you tell me your brig—” She noted Jeb’s jacket. “A general?” “Third Corps, Heth’s Division, Fourth Brigade. Wh—where are my boys?” The woman scanned the paper. “Some in hospitals along the Chambersburg Pike. Some in Cashtown.” Her face lit up. “The Bradshaws. I know they have room available.” She glanced at the teamster. “You know the place? Just up the Mummasburg Road?” The man nodded, then started the wagon north on Baltimore. Jeb remembered running through this street on the first day of battle, after Lee’s army gained possession of the town and pushed the Union forces to the south. But now, with the scattered remains of war in evidence, he hardly recognized it. As he traveled in the opposite direction, he was forced to observe the path of destruction his army had wrought. He prayed that Vicksburg, his home, currently under siege, would not have to endure a similar fate. A house drew his attention. A shell had ripped a hole in the second floor of the once grand estate, shedding light on the shattered furnishings. Eyeing a looking glass, the same shape as one that had hung in his father’s study, Jeb battled a wave of homesickness. Wakefield Plantation, built at the turn of the century by Jeb’s grandfather and christened for his bride’s family name, had passed down to Jeb’s father, Jackson. There, Jackson and his wife, Rebecca Simpson, of the Atlanta Simpsons, had resided for more than twenty years and raised four children, Jeb being the eldest. The epitome of grandeur and splendor, the lavish acreage became the envy of Warren County. An architect’s masterpiece, Wakefield was an estate designed for laughter. But the laughter had long ago ceased, even before war gripped the nation. One act of senseless violence had torn the clan apart, altering their lives forever. Thunder rumbled as Jeb wondered how his mother would take the news of his wounding. For all he knew, he would die in this enemy town. It pained him to think of what it would do to her. Especially after losing his father last year; losing his sister, Belinda, the year before that; and his brother, Charles, dead more than ten years. At least Charles’s surviving twin, Caleb, still lived with their mother in Vicksburg, but Southern conscription would likely drag him into the fight. When the wagon rolled past the college on Mummasburg Road, Jeb knew he had to write a letter to Vicksburg, telling his family of his survival. With a wounded left arm, however, he’d have to enlist the aid of a friendly soul, if he could find one. And with Vicksburg surrounded, would his mother even receive the letter? These questions plagued him until the wagon slowed, then stopped, before a two-story house. Turning, the teamster smirked in sadistic pleasure. “Well, Johnny Reb, welcome to your new home.” The red brick house stood isolated. Placed back from the road and shaded by oaks and walnuts, it would have had the air of peaceful solitude if not for some telltale signs of strife. A red flag—actually a vermilion shawl—clung to the front door, signifying a hospital. The brick walls displayed pockmarks of bullet holes. Windows bore shattered glass. The splintered remnants of a fence lay about the yard amidst several fallen horses. And, as Jeb had observed in every direction from the time his wagon ride commenced, bloody rain puddles stained the white-stoned path. The reek of disinfectant, festering wounds, and fecal matter fouled the air, expunging all traces of sweet summer fragrances. Kettles and caldrons, suspended from cross pieces on upright poles over open fires, added pungent vapors into the mixture. Rain-spattered, mud-covered, half-naked Confederates confused the lawn. From privates to colonels, they waited with terrorized faces for a surgeon’s examination. Others with oozing stumps, deprived of so much as a straw pallet, waited for their turn to die. War’s babble wafted from the house, not the pandemonium of an actual battle, but war just the same. Articulations of agony clogged the air, sobbing, moaning, dying. Hideous shrieks forced Jeb’s attention to the house’s open windows, and what he saw, more bloodcurdling than the sounds, sent chills up his spine. A collection of human body parts—legs, feet, arms, hands—had formed Shastas of bloody flesh in crushed flower beds. Jeb took a deep breath of the rank air and prayed. Here it was, the place he would die, or worse, suffer amputation. Soldiers were being mutilated by men who deemed themselves surgeons. More like butchers. If they didn’t know how to mend it, they cut it off. Yes, he thought, the ravages of war had found this once-peaceful home. His new home.

ISBN: 1-59279-016-X

The Reviews Home | The Novels | The Shorts | The Rest | The References The Author Bio | The Ongoing Battle | The Awards | The News Writing Links | Writing Rings | History Links | History Rings Sign Guestbook | View Guestbook © Copyright 1999, 2000, 2001 Trace Edward Zaber UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION AND DISTRIBUTION STRICTLY PROHIBITED. |