Added 29-12-19

Updated 2-8-25

This article should be read in conjunction with that on tanks.

“tanks are no longer a supporting weapon of infantry - almost the opposite - tanks must not be held back by old‑fashioned infantry pace. Therefore infantry should best be carried in vehicles”

Hans Guderin, 1937. (from “Tank Warfare”, Chapter 7 by Kenneth Macksey)

Armoured transports, be they APCs, IFVs, ESVs or CEVs, are an important element of combat operations.

Despite this, it is my belief that the mature form of this concept has yet to become common.

The CFE Treaty defined an APC (Armoured Personnel Carrier) as an infantry squad carrying vehicle with a gun of less than 20mm, and an Armoured Infantry Fighting Vehicle (AIFV) as having a cannon of 20mm or greater calibre. While this is a legal, rather than a technical, definition, it provides a useful rule of thumb.

In the following article, “APC” is used for an armoured transport for at least a fire-team, of any branch, except were specifically stated otherwise.

Some unsuccessful experiments with transporting infantry in tanks were made in World War One. The nature of armoured vehicles of this time were such that travel was so uncomfortable and nauseating, troops could not fight afterwards.

Arguably, the first successful armoured transports were the armoured half-tracks used during the Second World War.

The machine guns of World War One seem to have been the threat foremost in the designers’ minds.

The open-topped configuration usually used seems to indicate that artillery and mortars were seen as less of a concern.

Post-war vehicles added overhead cover but were still lightly armoured, the primary design criteria seeming to have been their ability to operate in the expected NBC environment of World War Three. The full implications of the Bazooka Age were not appreciated in many quarters.

Some vehicles, like the M113 and BMP-1, have been important steps up the learning curve. Lightly armoured vehicles like the M113 and MT-BL still serve in a host of useful support roles.

There have been some mistakes, too: flawed side-branches of the evolving family tree, such as the Stryker and its overweight, poorly-armoured ilk.

Now, after many decades of combat operations, we have ample evidence of what the primary threats that a vehicle will face are.

Foremost of these are RPGs and mines/IEDs, with ATGWs and fragments also concerns.

Attacks on vehicles often occur outside the expected combat area.

It should be obvious that personnel carriers need to be better protected. In fact, they and other front-line vehicles need a level of survivability more on par with that of tanks.

To understand my proposals for APCs and IFVs, it is necessary to review how APCs and IFVs are actually used.

Theoretically, one of the roles of mechanized infantry is to support tank forces.

In most armies, tanks and infantry belong to separate units, and usually distinct branches.

In practice, tanks and infantry seldom have the opportunity to train together. Different exercises usually see different units paired up. In peacetime, there is little opportunity to establish the trust and rapport that is needed for effective tank-infantry teamwork.

A few nations field both tanks and infantry within the same unit. In some of these, however, infantry are in the minority and there is a potential for insufficient dismounted manpower.

Many of the missions assigned to mechanized infantry are the same as those conducted by other varieties of infantry. The only difference is that each mechanized infantry squad has its own, organic APC or IFV. A mechanized infantry battalion is effectively a conventional infantry battalion with a potential parking problem!

Infantry fight dismounted. Once an infantry unit is on foot or in foxholes, what happens to their vehicles?

Some APCs may be used to patrol or screen the perimeter. Some may be positioned to provide fire support. Some may be used to move reserves or reaction forces. Some may ferry supplies. But only a relatively small proportion of the organic vehicles may be used in this way. A mechanized infantry battalion may have in excess of 50 APCs. Unused organic APCs will need to be located within easy reach of the infantry, but safe from enemy artillery, air-strikes or sabotage.

A considerable body of evidence over the past few decades confirms that tanks and infantry are most effective when they are fully integrated. Such relationships have often been established during long-term conflicts. However, once that conflict is over, these partnerships have usually been broken up.

Tank formations need their own organic infantry force. A tank company should have equal numbers of tanks and troop-carriers, each carrier with its own dismount team or squad. Tankers, carrier crews and dismounts work, live, and train together. Personnel may rotate between the different roles within the unit.

To avoid confusion with the more traditional configuration of mechanized infantry, I prefer to designate the dismount elements in a tank unit as “armoured pioneers”. I discuss this in greater depth elsewhere.

Armoured pioneers have supporting tanks as their primary role, and are thus primarily a force for high-intensity warfare.

Other forms of infantry, however, have a role across the entire spectrum of conflict, and for many of these roles they will need adequately protected transport.

Most infantry battalions need to reduce their holdings of organic vehicles, armoured or otherwise.

Field companies should have as much equipment as possible that is man-portable.

Heavy companies should have crew-portable equipment designed for dismounted operations.

Since infantry fight dismounted, their main criteria for a vehicle is to move them safely to where they are needed. This is where the “patch” concept comes into play.

I believe that very few “traditional” (tankless) configuration mechanized infantry units will be needed.

Protection is obviously a priority for an armoured transport.

Operations in the Bazooka Age require all around protection, observation and firepower.

As well as active protection systems, a vehicle should have a good level of more conventional armour.

Combat experience confirmed that the greater vulnerability of many lightly-armoured APCs/IFVs was a problem when they were used to support more heavily-armoured vehicles.

Tanks are more vulnerable without infantry support. An obvious strategy is to separate the tanks from the infantry, or to disable the infantry carriers.

A lower level of protection may result in a reduction of “practical/battlefield mobility”. If an APC is more vulnerable to hostile fire than the tanks it accompanies, it may be obliged to take a different route, isolating tanks from infantry support should they need it.

Many of the world’s current combat vehicles had been designed for early‑World War Two‑type operations without a full appreciation of how the descendants of the bazooka and panzerfaust would re-shape tactics.

Both the Russians and the Israelis have created “Tank Personnel Carriers (TPC)” from obsolete T-55s.

The conversion of tank hulls into personnel carriers actually dates back to the Commonwealth “Kangaroos” used during World War Two.

The kangaroos offered medium-tank-levels of protection and tracked mobility.

A combination it took APC designers several decades to rediscover!

Predictably, purpose-built, medium/heavy-APCs/IFVs have now been created, the Israeli Namer being claimed to be the best-protected combat vehicle in the world, with a level of armour superior to the Merkava IV tank.

The concept that infantry that manoeuvre with tanks need more protection has gained some acceptance. What is harder to get across is that infantry that operate without tank support also need high levels of protection.

As Richard E. Simpkin notes:“...Mechanized and quasi-guerrilla forces are essentially complementary. The one uses good ground, the other bad. The delay, disruption and weakening achieved by either one are prerequisites for the other to get into business.”

Put another way, mechanized/mounted/manoeuvre forces are most effective in open country; dismounted/quasi-guerrilla/infantry forces are more effective in close country.

In many armies, there is an assumption that any better armoured transport vehicles should be part of a tank force, while other branches should only use lightly-armoured or even unarmoured transports.

As I have discussed elsewhere, this is a logical nonsense. Forces without tanks are, if anything, more likely to be attacked while in transit.

The primary role of a guerrilla is harassment, and a fundamental principle of warfare is to engage when or where an enemy is unprepared.

All infantry forces are likely to face attacks when they are in transit. All forces that move by ground vehicle must be provided with vehicles that have adequate protection.

A successful manoeuvre force will eventually near its ultimate objective and very often this is likely to be in an urban area.

Above and elsewhere I have suggested that an armoured company include its own organic contingent of dismounts, which I designate “armoured pioneers”

Irrespective of mode of transport, it is essential to grasp that all infantry and armoured pioneers are a dismounted combat system.

Vehicles cannot search buildings nor look under bushes. Possibly in the future there will be drones that can perform some of these roles, but foot soldiers are not going to disappear any time soon.

Useful although the armoured pioneers will doubtlessly be, a mission such as an operation in a large urban area will require a much larger contingent of dismounted infantry and engineers than the armoured pioneers in an armoured battalion can provide.

Richard Simpkin was an advocate of an armoured force containing a balance of tanks and “in-house infantry”(armoured pioneers), but also maintained “I am equally convinced that such a force in turn requires to be balanced by an equal and separate force of dismounted infantry”.

Therefore an armoured taskforce will need to include an attachment of infantry. These infantry will need sufficient mobility to keep up with the tanks travelling to the objective, and sufficient protection to survive their transit through the threats of “tank country”. Rather than these infantry being with the force to support the tanks, the tanks and armoured pioneers are creating a path for the infantry to reach their objective.

What does the above mean in terms of hardware? Part of this has already been discussed in this article.

While dismounts are most effective dismounted, situations will arise when it will be necessary to engage an enemy while mounted on the vehicle.

A time-proven useful feature for any troop-carrier vehicle is a large roof-hatch over the troop compartment.

There will be situations when SLMs, ATGWs or MANPADS need to be fired from the vehicle. A large roof hatch allows such weapons to be brought into action with relative ease.

The roof hatch will serve other functions, such as launching reconnaissance drones or loitering munitions. It may be possible to operate a platoon/commando mortar from the roof-hatch.

The roof-opening also serves as a “mobile-foxhole”, allowing for all-around observation and fire. Some Israeli M113s featured projections (merlons?) that provided some cover for troops using the hatch.

In hot climates the roof hatch provides much needed ventilation!

The large turrets fitted to some APCs/IFVs may prevent the inclusion of a usefully sized roof-hatch. This design approach should be avoided.

Early models of IFV/MICV often featured firing ports so the infantry could use weapons while mounted.

Infantry should be dismounted if an enemy is known to be within a few hundred metres, so how likely it will be for firing ports to be used is open to question.

Firing ports fell from vogue in favour of thicker armour protection. If troops need to fire from the vehicle, a roof hatch often proves more versatile. Only thinly armoured vehicles are commonly now seen with firing ports.

Firing ports do allow occupants to engage threats that may be within the dead zone of roof-mounted weapons. Such situations are likely to occur when fighting in built-up areas.

Vision blocks or periscopes for the occupants of the troop compartment may prove useful, even if firing ports are not present.

For brevity, this and the following sections will only consider two variants of APC/IFV:

• The first type of vehicle and role has eloquently been called a “battle-taxi”. The primary role of this vehicle is to move infantry (or other personnel) from one location to another.

Like a taxi, the APC/IFV may not “belong” to the troops riding in it, and the crew may be from another unit or branch, as with the proposed carrier attachment battalion (CAB).

• The other vehicle-type/role I have called a “Armoured Pioneer Fighting Vehicle” (APFV).

APFVs provide close-support for tanks. Ideally there would be one APFV and dismount squad for each tank or tank equivalent, and they would all be organic to the same unit, used to training and fighting together.

The APFV (or just the CSV variant) would incorporate basic recovery equipment for the retrieval of damaged tanks and carriers.

APFVs will need to manoeuvre with the tanks they support. They may be required to provide support fire for the tanks or for the unit’s dismounted personnel.

The job description of the armoured pioneers and their vehicle might broadly be described as to “keep the armoured unit moving”.

For the armoured pioneers, it will clearly be useful if their carrier (APFV) is based on the same family of vehicles as the tanks they operate beside.

The maintenance and logistic problems of maintaining several types of vehicle is one of the excuses some armies have made for not forming tank units with organic armoured pioneers/infantry.

If using the same family of vehicles for the tanks and carriers is not practical, the vehicles should share as many components in common as practical.

Facing similar threats to the tanks, APFV will have a comparable level of protection (AF-HE/RPG/F+) to the vehicles they support.

Units intended for homeland defence are likely to have well-protected vehicles, while expeditionary units may have to field lighter tanks and APFVs.

The battle-taxi carriers used by the infantry are likely to closely resemble the carriers of the armoured pioneers, and commonality of components is obviously prudent.

The threat of ambush using IEDs or RPGs favours the use of well-armoured, heavier battle-taxis where practical.

Larger production runs lower unit cost, so there are economic and development savings to using the same basic vehicle for a family of MTAFVs including tanks, thunderbacks, APFV, medium battle-taxis, command vehicles, air-defence and related support variants such as recovery and bridging.

A good level of armour means mass, which indicates a tracked vehicle will be needed to reduce ground pressure and increase mobility.

The APFV and medium battle‑taxi will be MTAPCs (“medium tracked armoured personnel carriers”).

Wheeled vehicles may be able to force their way through thick mud, to varying degrees of success.

Many potential adversaries are well accustomed to operating in deep snow and cold weather.

Operations in snowy conditions require vehicles that are able to move across the surface of snow, rather than through it.

In 1945, Kangaroo APCs used their superior mobility to deliver a successful attack on the previously impregnable Wanssum Wood during a blizzard.

All-terrain, all-season capability is important!

The numerous discussions of the advantages of wheels or tracks are irrelevant unless size, mass and terrain is included in the consideration.

The superior rough ground capability that tracks provide will prove useful negotiating rubble and other obstructions during urban operations.

Tracked propulsion offers a greater choice of potential routes, but in many parts of the world choices of route are limited, so protection against attack remains a priority.

The supposed advantages of wheels over tracks, simplicity and speed, disappear as size and mass increase.

Ten to twelve tonnes seems to be the upper limit for practical wheeled armoured vehicles, with keeping mass in the single figures preferable. This restriction does not permit high levels of protection.

Level of protection, armament, equipment, mobility and mass are all interconnected.

The components of a manoeuvre force should have a good level of operational and tactical/battlefield mobility.

Vehicles must not be too heavy to use most of the bridge and road systems available in their operational area.

When in combat, vehicles should be capable of rapidly sprinting between areas of cover.

When moving out of cover to fire, vehicles should spend the minimum time exposed as they acquire, attack and then retreat to safety. “Firing exposure time” is a product of low-speed acceleration both forward and in reverse.

For a manoeuvre force primarily intended for homeland defence in a developed nation, APFVs, battle-taxis and most of the vehicles they support or move with should probably have a mass of 38 tonnes or less.

Vehicles of this size and mass have the potential to form a very useful family of variants, including medium tanks or equivalents.

Vehicles for expeditionary and airborne forces will need to be lighter to maximize their strategic mobility.

In some parts of the world extensive areas of alluvial soil limit vehicle mass to 10 to 20 tonnes.

Both homeland defence and expeditionary forces will use light variants of APC for various support roles and reconnaissance.

How best to arm APCs and IFVs is a somewhat contentious issue.

A number of manufacturers offer offer vehicle turrets mounting various combinations of cannon, machine guns, missiles, grenade launchers and sensors. How useful is it to give a poorly protected vehicle a potent armament if there is a low likelihood of it surviving long enough to make much use of it?

In this article, an infantry fighting vehicle is proposed with hull-mounted machine guns and automatic grenade-launchers, and a main turret with an autocannon, 60mm gun-mortar and a quartet of ATGMs.

Cost, mass and space restrictions will probably prevent all these capabilities and features ever appearing in any infantry-carrying vehicle that actually gets adopted for service.

Dismounts are most useful dismounted, and it might be argued that the above design with multiple crewed turrets might tend to discourage this. If the infantry are dismounted to engage a nearby foe, many of these weapons would be unmanned.

Heavy armaments may be more usefully employed on non-troop-carrying variants of vehicle.

For conventional infantry, their primary requirement for armoured transport vehicles is to move them between positions or towards an objective. Mobility and protection are higher design priorities than firepower.

An argument may be made that the necessary vehicle needs to be mobile and well protected, but only needs a relatively modest defensive armament.

If an enemy is known to be within a few hundred metres, the infantry should be dismounted, making the provision of additional vehicle-mounted weapons superfluous.

This argument does, however, raise the question: “defence against what?”

The Need for Cannon?The definition of an IFV is an APC with a cannon. Few dispute that a cannon is needed, and the trend is generally to fit bigger and heavier weapons. In “Mechanized Infantry”, Simpkin observed that the military rationale of an IFV with an automatic cannon was a choice it was hard to justify. Very little attention is paid to the roles such cannon will be put to. An automatic cannon on an IFV provides very little defence against modern combat aircraft. Modern stand‑off weapons allow aircraft to operate at ranges, altitudes and speeds well beyond the IFV cannon’s capability. Modern effective air defence requires more sophisticated fire control and targeting systems, and usually a missile solution. The most likely scenario for an aircraft to come with range of an IFV cannon is when the vehicle is defending a landing zone against an enemy. In such a situation, any cannon or HMG will have a deterrent, spoiling and occasionally lethal effect. The surface‑to‑air role of a modern IFV’s cannon is minimal. The heavier the gun, the less responsive and the less practical it becomes. The rationale for bigger IFV cannon is often given as to counter a hypothetical slightly heavier armoured future enemy IFV. However, IFVs with tank‑levels of protection already exist and are likely to have significant resistance to such cannon. It seems unlikely that a future battle will allow IFVs to duel with just the enemy IFVs its cannon can penetrate. Tanks, infantry and vehicles with tank‑level protection are likely to be present too, and will need to be dealt with. Adopting bigger guns for IFVs is grounded in the false assumption that “like will fight like”. IFV designers seem to be retracing the evolution of the anti-tank gun. As we know, the ultimate solution in that story was not an even bigger gun, but the missile. An IFV’s armament needs to have the capability to support its dismounted troops. Soft‑skinned vehicles can be attacked with machine guns. Entrenchments are better attacked with automatic grenade-launchers, mortars and large explosive shells than by automatic cannon fire. Air‑burst cannon rounds of 30mm or greater calibre do have a capability against light entrenchments. With some thought, it will be seen that cannons have fairly limited applications for a modern IFV, especially when the presence of heavily armoured threats and targets necessitate the carrying of anti‑armour missiles. The trend for mounting heavier and heavier automatic cannon on IFVs needs to be halted, and priority given to weapons and ammunition that are more suited to supporting the infantry and defending a vehicle. An LW30 cannon with air‑burst ammunition would be optimal for the few instances when cannon fire may be needed. Existing designs of vehicle should be provided with missile-launch capability and automatic grenade-launchers rather than bigger cannon. Automatic grenade-launchers with air-burst capability have been available for several decades. |

Many APCs/IFVs mount just a machine gun and/or 20mm cannon for local defence, and to provide suppressive fire as the infantry dismount. Persisting in considering such weapons as an anti-aircraft defence is overly optimistic given the range and capability of modern air-launched weapons!

Troop-carrying vehicles may also be expected to fire in support of their dismounted personnel, whether during a planned dismounted operation or in response to an ambush. In such a situation, an enemy may be entrenched and not particularly vulnerable to direct-fire.

Modern attack helicopters probably need more gun than a machine gun, but how much? Will attack helicopters even come into cannon range?

The provision of an autocannon has become a defining characteristic of an IFV.

The 30x176mm Bushmaster II has become a common armament for many vehicles. Many Russian/CIS vehicles now mount a variant of the 30x165mm 2A42 or 2A72.

Heavily armoured carriers such as the medium APFV and battle-taxi could mount an autocannon such as the 35/50mm Bushmaster III. The recoil force of a 35/50mm is two thirds that of the Israeli 60mm HVMS, the latter being around 6,000 kg. The HVMS has been successfully mounted on an M113 with a 1.5 metre diameter turret ring. Since a 35/50mm cannon is only 40% the mass of the 60mm HVMS, it may be practical for the former to form the armament for the medium and lighter models of APFV and battle-taxi.

The desire for larger calibre weapons must be weighed against actual practical utility, however.

Just because a system can be fitted does not mean it is desirable.

Current helicopter-missile systems can engage vehicles from greater than five kilometres range when terrain and visibility permit, putting the helicopter well out of effective range of most cannon that any troop‑carrying vehicle might realistically mount.

It may be argued that the presence of cannon on an IFV (or other vehicle types) forces the helicopter to keep its distance and therefore gives the vehicles greater time to employ countermeasures.

When helicopters have to engage at shorter ranges, the provision of autocannon armament may be significant.

Unmanned aerial systems may also operate at shorter ranges.

Effective range of light cannon against helicopters is 2,000 to 2,500 metres, regardless of cannon weight or calibre. Accuracy and hit-probability, rather than power, is the limiting factor.

At 2,000 to 2,500 metres range, an LW30 cannon is just as effective as heavier choices of cannon.

Another role commonly proposed for the IFV’s cannon was to give it capability against lightly armoured vehicles such as other IFVs and APCs.

Currently, we are seeing the adoption of slightly larger calibre (but much heavier) cannon in anticipation of slightly better armoured IFVs.

Piecemeal increases in cannon power fall into the trap of designing “like against like.”

We already are seeing APCs and IFVs with tank-levels of protection that will be highly resistant to the proposed upgrades of IFV cannon.

Most of the vehicles that will be encountered on a future battlefield will be tanks or have tank-levels of protection.

Any cannon that can deal with such targets is likely to be too heavy and bulky for a practical troop‑carrying vehicle.

As more heavily armoured IFVs gain acceptance, the anti-vehicle applications of a cannon on an IFV may become less significant. Any poorly protected vehicles encountered are likely to be equally vulnerable to machine gun fire.

While its anti-vehicle and anti-aircraft potential is somewhat diminished, the autocannon remains useful for firing on entrenchments and against enemies within civilian buildings.

Trying to fit a troop carrier with the largest cannon possible is not the best option. A more practical approach would be to select a cannon optimized for the targets that it is most likely to be used against.

The changing roles for the autocannon suggest that an IFV may be optimally armed with a lighter weapon such as the 30x113Bmm M230/XM914 or ASP-30.

Arming a troop carrier with light (LW30) cannon extends the vehicle’s capability against light vehicles and field fortifications.

Penetration of brick for the 30x113Bmm (LW30) can be expected to be similar or better than that of a 40mm HEDP grenade. Cannon fire may be used to create access points in walls for infantry, although podded rockets or SLMs deployed by infantry may be more effective.

The LW30 cannon also provides a more potent response to ambushers.

LW30 weapons will become even more useful and versatile when LW30 programmable air-burst (ABM) ammunition for them becomes standard.

An LW30-ABM cannon would be well suited for arming a battle-taxi or APFV, exceeding the performance of heavy machine guns, automatic grenade-launchers and smaller calibre cannon.

LW30 weapons are lighter than many smaller calibre weapons, allowing a more useful quantity of ammunition to be carried, and helping keep the mass of the vehicle within practical limits.

The LW30 cannon also provides useful firepower during low-intensity and counter-insurgency conflicts, and other situations where troops may be deployed without tank support.

Carriers armed with light cannon may serve as an effective manoeuvre force.

At least one manufacturer is currently offering remote weapon stations (RWS) mounting an M230/XM914 cannon with a machine gun and ATGM or SHORAD missiles.

One of the roles of an APFV is to protect tanks and other vehicles from enemy infantry and anti-tank teams. A cannon may prove too potent in some such situations, since there is a chance of damaging friendly vehicles.

Air-burst mode for cannon and mortar shells may be only a partial solution.

In such situations, machine guns may be the preferred option.

Machine guns are likely to be the primary weapons of APFVs, and considerable quantities of MG ammunition should be carried.

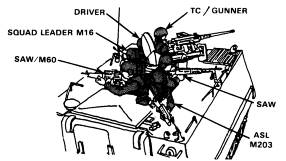

During an ambush, or when deploying close to an enemy, the capability to simultaneously fire into different sectors may prove useful.

Ambushes tend to be made from multiple and/or unexpected directions so it is prudent to not have a single weapon position that may only fire in one direction at once.

A troop compartment roof-hatch of a carrier should include on each side the provision for mounting an elbow mount for a light or medium machine gun to serve as an ACAV-style “wing-gun”, complete with gun-shields.

These wing-guns will be useful when there is a likelihood of ambush or attacks from several quadrants.

The machine gunners should be supported by comrades using grenade-launchers as auxiliary weapons.

Provision to fit a “tail-gun” to the vehicle should also be considered. The roof-hatch of some M113s had a mounting point on the underside. When the hatch was open, the fitting could be used to mount an M60 machine gun. A similar fitting compatible with more recent weapons might prove useful.

A trend seen in many Eastern European AFV upgrades is to supplement the MG and/or cannon armament with an automatic grenade-launcher mounted on the turret. This provides an individual vehicle with the capability to engage a threat with both high-angle and direct fire.

A trend seen in many Eastern European AFV upgrades is to supplement the MG and/or cannon armament with an automatic grenade-launcher mounted on the turret. This provides an individual vehicle with the capability to engage a threat with both high-angle and direct fire.

APCs with the modification first began to appear on BMPs and BTRs during Russia’s operations in Afghanistan.

Technologies such as programmable air-burst ammunition may give vehicle-mounted autocannon of 30mm or greater calibre a useful capability against targets in cover, making the provision of a separate automatic grenade-launcher unnecessary.

That said, adding automatic grenade‑launchers to existing IFVs and APCs would be a much more useful update than providing them with new, even larger cannon.

IFV need the capability to create smokescreens to support dismounted infantry. Smoke grenade dischargers and VEESS serve for local defence.

The ability to lay smoke at more distant locations would be useful when infantry operate several hundred metres from their vehicle.

Some vehicles should carry pods of smoke rockets. One option is the 2.75" FFAR. Since the usual operating range will only be a few hundred metres, smaller rockets resembling the 50mm Rattlebox, or the 51mm FIROS‑6 may be more suitable.

A pod of smoke rockets allows for a more rapid build up of smoke than can be delivered by a single mortar barrel.

A proposal from the Losik/Brilev article I do like is to arm a vehicle turret with both an autocannon and a 60mm gun‑mortar.

An APFV with a 35/50mm or LW30-ABM autocannon and a 60mm gun‑mortar would be an effective support platform for both its dismounts and the tanks it accompanies.

HE, illumination and smoke rounds from the mortar may be used to disrupt enemy defences and anti-tank positions.

The canister load for the gun-mortar may be used to “back-scratch” other vehicles.

1.5 metre diameter turrets mounting cannon, machine guns and 60mm gun‑mortars are already in use on some models of armoured car.

The battle-taxi could mount the same armament as the APFV, but for reasons of economy, it is more likely that the majority will just mount machine guns and an LW30 air-burst cannon. Possibly, a quarter of the battle-taxis will mount both LW30 cannon and 60mm gun‑mortars, enough to make one gun‑mortar available to each mounted infantry platoon.

The capability for the vehicle to launch ATGWs must the weighed against cost, added complexity and likelihood of use.

My current thoughts on arming battle-taxis and APFVs with ATGWs are recorded in more detail elsewhere.

Mounting points for ATGWs may also mount rocket pods.

Guided weapon attacks from ground-vehicles will mainly be from platforms such as Thunderbacks, and the loitering munitions and LR-AGTM operated by the artillery.

New designs of personnel carrier or turret will not routinely mount such ATGWs, but should include the provision to fit a mount for infantry‑ATGW systems when required.

This option will probably be more common for vehicles in expeditionary forces and those that face a considerable tank threat or lack their own tank support.

Infantry‑ATGW missiles carried in the vehicle may either be launched by the vehicle or from dismounted positions, keeping the carrier out of sight.

As an organic part of an armoured platoon, the APFV may be expected to contribute to the anti-tank fight, but the exact form this contribution should take is open to debate.

Cannon and gun‑mortar fire will have limited effect on enemy tanks and medium‑IFVs.

Should the vehicle be providing covering fire to the platoon’s dismounted teams, or launching heavy missiles?

If teams are not yet dismounted, would the vehicle be better used moving dismounted ATGW teams to where they are most effective?

It seems only prudent that as a matter of routine, CAB battle-taxis and APFVs are stocked with infantry-portable ATGWs and anti-tank SLMs.

The primary weapon of the APFV for close support is the rifle‑calibre machine gun(s). Other weapons may damage the tanks and carriers the APFV is defending. A LW30-ABM cannon may be used for other targets, including entrenched infantry and suspected anti‑tank sites.

A battle‑taxi many be armed with a heavy machine gun or automatic grenade launcher. More potent and more versatile is an LW30-ABM cannon and medium machine gun(s).

A LW30-ABM cannon is effectively complimented by a 60mm gun‑mortar. The gun‑mortar can provide screening and illumination fires and be used to engage enemies behind cover.

One strategy that will help create more-compact combat vehicles is acceptance that an infantry carrier does not have to accommodate a complete squad.

One strategy that will help create more-compact combat vehicles is acceptance that an infantry carrier does not have to accommodate a complete squad.

There is some merit in allocating no more than six dismounts or a half-squad to each vehicle. This increases passenger comfort, and leaves more room for extra supplies and equipment.

If a squad uses at least two vehicles to travel, a stuck vehicle has immediate assistance.

The larger the capacity of a vehicle, the more complicated boarding and debussing seems to become.

If a vehicle is disabled, there is room on another vehicle for its crew and passengers to squeeze in.

Ambushing multiple vehicles is more problematic than attacking a single one.

This said, some current vehicles such as the HMMWV and most of its proposed replacements are too small.

An infantry carrier should have a cargo capacity of around two tons. With weapons, equipment, ammunition, food and water, each infantryman must constitute at least 200-250 lbs of load.

While the HMMWV is too small and underpowered for use as an infantry carrier, it is used for other roles that it is too big for.

This article gives a good account of the HMMWV’s weaknesses as a reconnaissance platform.

Vehicles such as Toyota Land Cruisers and Hiluxes can more cost-effectively perform many of the non-combat roles that HMMWVs are used for.

In this article I suggest that a Toyota “mimic” vehicle may prove a useful supplement to more overtly military tracked reconnaissance vehicles.

It is unlikely that each infantry company will have an organic contingent of medium/heavy-APCs or IFVs.

This is financially improbable, and in fact not desirable.

This is where the “patch concept”, and specifically the Carrier Attachment Battalion (CAB), show their merit.

During the Second World War, the newly introduced Kangaroo APCs were primarily used by the Canadian 1st Armoured Carrier Regiment and the British 49th Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment.

These regiments included their own vehicle crews, signals, and maintenance and repair sections.

A troop (platoon) of twelve carriers could move an entire company of infantry. Each carrier regiment (battalion-size) could move two battalions of infantry.

The US Army Pentomic infantry division structure centrally pooled its APCs (M59s) as part of the transport battalion. (see p.35 Infantry Magazine July 1957)

If a force (infantry or otherwise) is to be moved through hostile territory and needs protected transport, it may be “patched” with a Carrier Attachment Battalion (CAB) subunit to move it.

This makes infantry battalions more versatile, and allows the army to operate a smaller number of higher quality vehicles.

The CAB provides the carriers, vehicle crews, maintenance and repair teams, recovery vehicles, and the associated support staff and infrastructure.

Similarly, the configuration of infantry battalion suggested elsewhere might be easily moved by helicopter, airliner, truck, or rail, as local criteria dictate.

Different varieties of patch formation may provide a force with light vehicles, LPMVs, helicopters, IS vehicles or river boats.

The increased level of protection better armoured vehicles provide offers some interesting tactical options.

One of these might be termed “Assault Under Barrage”.

A well-armoured, tracked armoured transport (“assault wagon?”) is unlikely to be affected by close-proximity detonations of 155mm howitzer or heavy mortar shells.

A force of infantry or armoured pioneers in such vehicles could move to within 30 metres or closer of an enemy position under bombardment, safe from RPGs and other anti-tank fires due to their suppression by the artillery.

The assaulting force would also be protected from some of the direct-fire weapons that supporting units might be using against the enemy position.

Vehicle autocannon and gun-mortars with air-burst ammunition will be more effective against entrenched troops than more traditional weapons.

The well-protected MTAPC vehicles described above will not be suitable for all roles.

Many support roles are more effectively served by lighter tracked vehicles.

A very large number of M113s are still in service globally, and the design has proven service record.

It is logical that any future light tracked support vehicle be an evolutionary design based on the M113-series LTAPC and its components. The main improvements that need to be addressed are mine-resistance and hybrid-electric propulsion.

The basic support vehicle might be based on the proposed flatbed Uta vehicle.

Some combat roles will also require lighter tracked vehicles. The heavily armoured vehicles are likely to be too massive to be easily moved by helicopters or light transport planes, suggesting air-mechanized helicopter and paratroop forces will need a lighter but necessarily less-capable armoured vehicle.

Rather than versatile, multi-role platforms, weight limitations may require a family of more specialized vehicles.

From the flatbed variant and a light personnel carrier variant would be derived a variety of useful variants. This includes reconnaissance vehicles, light tanks, mortar-carriers, air-defence, drone-carriers, C-RAM, cargo, tankers, engineer, command, recovery, repair, maintenance and others.

The basic light tracked combat vehicle will probably be a lightly armed APC or cargo track, complimented by a better-armed IFV/light tank mounting autocannon, missiles and mortar. The latter vehicle will perform in a light tank role as a reconnaissance and fire-support component of a force. Ideally this variant would have room for a small dismount scout element, but if not, dismounts can travel in an accompanying APC-variant.

Other cargo tracks provide additional ATGW, MBRL, SAM and mortar support.

This may be how the Russian VDV BMD-4M and BTR-D/MD are intended to operate together.

The British Spartan, Sultan, Samaritan, Samson and its various other variants provide another proven example of a very compact APC design.

Such lighter vehicles will be more vulnerable, but possibly this can be offset by the nature of operations they are intended for.

If amphibious, such lighter armoured vehicles may serve a useful reconnaissance role in heavier formations.

They may also be useful for civilian organizations that operate in adverse conditions.

Where practical, the light-track vehicles will share components with the more heavily armoured carriers.

Helicopter transported forces may need to adopt other solutions to increase ground mobility.

In his books, Richard E. Simpkin often advocates the M113 or similar as a general purpose “workhorse” vehicle.

In “Antitank” p.204, he also suggests unarmoured, tracked artillery vehicles of 8 to 10 tonnes, mounting either 120mm mortars or NLOS-ATGW. Such vehicles might resemble the LOHR VPX 40 or CT20 Oxford Carrier. This section of “Antitank” also mentions the Sultan Command Vehicle, presumably to serve as both as battery control and weapon crew transport.

For “heavy” forces, the above capability may be provided by M113‑based platforms such as M1064 and Exactor.

A lighter vehicle will be needed for forces that will be air‑lifted or heli‑mobile. Successful experiments were conducted fitting the M56 self‑propelled gun with alternative weapons including heavy mortars. The M56 massed 7.1 tonnes including a 90mm anti‑tank gun.

An alternative (or complimentary) approach for helicopter or airborne infantry, already seen in some armies, is the adoption of compact, unarmoured, amphibious vehicles such as the Supacat, Gecko and Chinese 8x8.

Air-mobile forces are an obvious choice to operate in close and “vehicle-proof” terrain, possibly conducting Simpkin’s “quasi-guerrilla net-operations”.

The requirement to perform this role will have an influence on the scale of vehicle issue.

For very light, aircraft deployed forces, bikes, quad bikes or similar seem to be the best options to increase their ground mobility.

A very light tracked utility platform, along the lines of the M29 Weasel or Universal carrier would also prove very useful to both military and civilian forces.

As an aside, I will mention an interesting design proposed by Richard E. Simpkin in Jane’s Military Review, second year of issue, 1982-3, p.144.

This design had the vehicle crew compartment sealed off from the troop compartment. The section leader had two observation positions.

The “clean” position was with the vehicle crew.

If the section leader had to dismount and became contaminated, there was a duplicate observation position and hatch for him in the troop compartment.

The troop compartment had a slide out liner of of boronated polyethylene for easy decontamination or reconfiguration of role.

This is probably overly complicated for a standard carrier, but such a configuration might be worth consideration if a dedicated CBRN vehicle was planned.

South Africa and Rhodesia were some of the only “western” militaries to take measures against the threat of mines/IEDs.

As the number of unnecessary casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan rose, the combatants began to purchase South African vehicles or produce their own versions.

Many of these MRAPs are large, heavy wheeled platforms designed to carry a squad or more. Such vehicles have problems moving over some types of terrain.

Experience over the last few decades suggests that “less is more”. Limiting a vehicle’s capacity to eight seats or less has a number of advantages.

• The reduction in mass and lower ground pressure gives the vehicle a more useful poor-road and cross-country performance.

• A more compact protected mobility vehicle is more useful in urban environments.

• Smaller size allows a thicker level of armour to be fitted for a given mass penalty.

• Appliqué armour permits the same platform to be configured as either a protected transport or a lighter, long-range patrol vehicle.

There are some missions where a wheeled vehicle is perceived as being preferable. These include internal security, quick reaction and rapid response forces, and many situations where travel is predominantly on roads or firm ground.

There are some missions where a wheeled vehicle is perceived as being preferable. These include internal security, quick reaction and rapid response forces, and many situations where travel is predominantly on roads or firm ground.

As noted already, the supposed advantages of wheels over tracks, simplicity and speed, disappear as size and mass increase.

If a wheeled vehicle is needed, it needs to be light, fast, reliable and possibly inconspicuous.

Usually described as “HMMWV replacements”, Light Protected Mobility Vehicles (LPMV/“Chasseurs”?) have the potential to replace overly large, lightly-armoured heavy-WAPCs such as the Stryker.

Two or three LPMVs for a squad are a tactically more flexible and agile choice than a single, very large vehicle.

In the past, wheeled combat vehicles have often been modified soft-skin vehicles. The death-toll from the use of HMMWVs in Iraq and Afghanistan clearly shows the shortcomings of this approach.

The more recent designs of these vehicles incorporate mine-resistant features. Vulnerability to RPGs and similar weapons remains a concern.

The British MRV-P requirement specifies operation “on all parts of the battlefield except for the direct fire zone”.

In future conflicts, expecting a clearly defined direct fire zone seems optimistic!

PMVs should be seen as transports rather than as fighting vehicles.

In my article on light auxiliary vehicles, I suggest that the majority of HMMWV roles may be filled by a pickup/shelter-carrier variant and a van-configuration variant.

Interestingly, the Oshkosh L-ATV/JLTV variants seem to be based on a two-door and a four-door pickup configuration. The proposed ambulance variant could form the basis of a van-variant.

The Thales Hawkei is a two-door pickup or a four-door personnel transport with a cargo-bed.

A useful command post variant, similar to the Saracen FV604, could be created from a box-body or shelter-carrier variant.

A nondescript, wheeled command post vehicle would prove useful to many types of units and organizations.

Australia plans to replace about one third of its Land Rovers with Hawkei.

Many of an LPMV’s potential missions and environments will require that the crew or passengers may easily board or disembark. For reconnaissance missions, doors facilitate the practice of dismounting to scout when necessary.

On the vehicle designer’s trilemma, the LPMV/Chasseur is towards the “mobility” corner, and attempting to increase protection or firepower beyond certain levels will diminish its primary virtues.

Mass of the platform limits armament options.

Typically, such vehicles are either armed with machine gun or an automatic grenade launcher (AGL). While mountings that may mount both a heavy machine gun and a grenade launcher exist, they have so far seldom been seen on this class of vehicle.

The LW30 weapons discussed earlier are probably the autocannon most suitable for mounting on LPMVs. These are lighter than many smaller calibre cannon and give a direct‑fire capability superior to both heavy machine guns and AGLs.

Vehicles of similar mass to LPMVs have been used with recoilless systems such as recoilless guns and ATGWs.

Examples are now being seen mounting pods of guided 70mm rockets. The photo above shows examples from Thales mounted on a Hawkei.

While LW30 cannon, HMGs and recoilless weapons offer considerable firepower, the low‑levels of protection of such vehicles calls into question their practicality for deliberate combat.

There is an obvious temptation to use LPMVs for the non-reconnaissance roles that were formerly the province of cavalry.

Vehicles with AGLs may have the option of firing from behind cover, giving them a practical role as indirect‑fire support “cartillery”. A dedicated variant, equipped with ballistic, navigational, positional and meteorological systems, and replacing passengers with additional ammunition, is a possibility.

Armament on LPMVs should probably be selected with consideration of its defensive capability and suitability for breaking contact. High rate of fire weapons such as the M3M, M134, 20mm M197/XM301 or GECAL .50 minigun are possible options.

Smoke‑generating systems and other countermeasures will be a priority. Smoke grenade dischargers and a “vehicle engine exhaust smoke system” (VEESS) will be standard fittings.

Not all support roles need tracks. Many armies operate both wheeled and tracked APCs.

One of the usual arguments for also having a wheeled APC is that of cost. Any platform that is considered should be something simple along the lines of Saracen, Bushmaster, VAB or Saxon.

What is NOT needed are expensive, bulky, heavy, lightly protected vehicles such as the Stryker.

Many of the roles of a wheeled APC are likely to be those other than troop carrier, so an adaptable, possibly modular design, may be prudent.

Many of the claimed advantages of a wheeled platform decrease as mass rises or ground softens.

To be useful and practical, the mass of a wheeled APC should probably be kept to under ten to twelve tonnes. Such a restriction will limit capacity and/or the level of protection. This mass limit is difficult to achieve if an adequately protected vehicle that can carry a full squad and their equipment is desired.

The purpose of an armoured personnel carrier is to move its occupants safely from A to B. If the vehicle cannot effectively traverse the intervening terrain, or it offers no protection against the attacks likely to be made on it, it is not fit for purpose. Hence, well-armoured, tracked MTAPCs, as described earlier, are a requirement.

It may be argued that if RPGs and mines are such an unlikely threat that tracked well-armoured MTAPCs are not needed, then conventional trucks or buses might be more useful for transport than a wheeled APC.

The question remains as to whether a “cheap” wheeled APC will actually be cost-effective?

Many support roles might just as effectively be filled by unarmoured wheeled vehicles.

Other solutions, such as trucks with armoured cabs, are another possibility for support vehicles

A wheeled, rather than tracked APC, might be useful to police and internal security forces. The role of such a vehicle complements and intermeshes with that of LPMVs. Wheeled APCs may be larger models of MRAP, useful when capacity is a priority over off-road mobility.

An IS vehicle (and low-cost wheeled APC) should be constructed from readily available military and commercial components. The AV Dragoon 300, for example, included components of the M113 and the M809 and M939 five-ton trucks.

For the IS/Police role, a “conventional” appearance, as seen with vehicles such as the Humber Pig, will be preferable to something that is more overtly tank- or armoured car-like.

Operation of these vehicles will mainly be on roads, so windscreens and good visibility for driving are design priorities.

Those who dismiss IS vehicles as “armoured-plated trucks” miss the fact that in some situations this is exactly what is needed! This statement also suggests that a logistic version of an IS vehicle might prove very useful.

A roof-mounted turret has limited applications for an IS vehicle. The width, length and height of the roof creates a considerable dead zone around a vehicle, which is easily infiltrated in the urban environments such a vehicle is likely to be used in.

A more useful fitting may be a roof-mounted observation tower or cupola. This would be provided with protected windows and various surveillance, recording and illumination systems. Firing ports in the superstructure would permit the launching of gas grenades and other non-lethal munitions. Some designs of vehicle superstructure allow a marksman and their weapon to be concealed in discrete readiness.

Firing ports in the vehicle sides and doors may have more application for defence than a turret if they are provided with adequate vision devices and armoured windows. Weapons compatible with firing port use must be available within the vehicle.

Size of the IS vehicle needs careful consideration. For roles such as riot-duty, manpower is a priority over firepower.

The vehicle must have sufficient power that it can push aside barricades.

It may not be so light that a mob can overturn it. However, we do not want a vehicle that is too big to manoeuvre in narrow streets where it might be needed.

In another article, I have proposed designs for dedicated road security and escort vehicles.

Since such a necessary capability is a low priority on most military shopping lists, we may see the IS vehicle used for this role too.

Such a role will probably require heavier armament. Features such as a large roof-hatch and provision for wing-guns will need to be incorporated in the design.

In the Osprey publication “World War Two Combat Reconnaissance Tactics (Elite 156)”, there is a passage: “[British] Recce units advanced under one of three protocols: 'move in green' - when enemy were unlikely to be encountered; 'in amber' - when contact was possible and speed was reduced; and 'in red' - when contact was likely, speed was greatly reduced, and close reconnaissance of possible enemy positions was conducted.”

The preferred system for “red” or “amber” scenarios is obviously with dismounted troops and medium carriers, with support.

For green and amber conditions, medium carriers may not always be available.

In the future, we may see increasing use of “mufti vehicles”.

If a sufficiently armoured military vehicle cannot be used, then an alternative is to use a camouflaged one that blends into the other civilian traffic using a road: protection by mimesis.

A military force should acquire an assortment of local vehicles of differing makes, models, sizes and colours.

Unlike an APC, a mufti vehicle is crewed by the unit using it and generally not occupied when that unit is dismounted. For some operations they may be treated as disposable.

An apparently civilian vehicle can often infiltrate an objective far more easily than a military one.

A civilian car packed with sensors can sweep an area for IEDs yet be ignored as a target over more military-looking vehicles.

Infantry patrols or other specialists can be covertly placed in an area without the attention helicopters or other military vehicles attract.

A mufti vehicle is not a fighting vehicle. Its role is to move its occupants and possibly to lay down smoke long enough for the troops to deploy.

Variants that can control drones, act as command/C4I vehicles, provide EW support or launch guided weapons are possible.

In another article I have discussed military vehicles designed to look like civilian vehicles.

Many decades ago, I was writing about possible military vehicles.

I noted that a light APC that externally resembled a panel truck or transit van might prove useful. Such a vehicle might have many useful applications for law enforcement or Operations Other Than War (OOTW).

I would not be surprised to discover there are companies that offer to fit armour and related features to commercial vans. There may indeed be some on the streets of your town right now.

A militarized transit van would have roles other than personnel transport.

If the movies are to be believed, vans are common choices for surveillance operations. They can also serve as command and control centres, for SIGINT, and for electronic warfare support to tactical units.

A roof hatch(es) would be useful for many roles, although given its height, the large dead zone will leave many potential threats too close to fire on. This is a vehicle that would find firing ports a practical addition.

Technologies such as vertical launch missile systems may even give them an artillery and air-defence role!

By the Author of the Scrapboard : | |

|---|---|

| Attack, Avoid, Survive: Essential Principles of Self Defence Available in Handy A5 and US Trade Formats. |

| |

| Crash Combat Fourth Edition Epub edition Fourth Edition. |

| |

| |