Added 27-3-15

Updated 29-5-25

It does not take a particularly well-polished crystal ball to predict that the use of drones will increase in the near future.

Not only will they increase in variety and capability, but also in the range of their users.

Mortar platoons that have their own drones are evolving into being both a fire support and reconnaissance asset.

There are a number of squad and platoon-level devices that can fly or roll ahead of a fire team to let them know what is around the next corner or behind the bushes.

I expect that we will soon see SWAT and MOUT forces using small drones that can negotiate stairs and use fibre-optics to peek under doors or through keyholes.

Aerial reconnaissance is now available even to individual fighters.

A particularly interesting development is drones that fly by gliding like birds, look like birds and can even seek thermals updrafts. Combined with solar power and a power reservoir for night operation, such drones could remain airborne for days at a time and be very difficult to distinguish form actual birds.

It would be difficult for an enemy to take cover every time a bird appears in the sky. His main defence against such observation would have to be to remain under cover as much as practical.

To locate such activity suggests another type of drone, perhaps something like a beetle that can fly to a location and sneak in by crawling. Attractive though this option is, it still has limitations. Our beetle drone could not open desk drawers to rifle through papers, for example.

There is another problem inherent to the use of drones. Most drones currently require some form of control signal since they are effectively remote controlled devices. Even if a drone has some degree of autonomy, it will still need to transmit its observations back to base.

One area where even the most primitive of insurgents seems keen to spend money is for sophisticated air-defence weapons.

They know that better equipped forces will try to use air-power against them. They also know that shooting down even one multi-million dollar warplane can be a considerable propaganda victory, especially if the pilot can be captured and displayed.

I believe it will not be long before an equal emphasis is placed on electronic warfare (EW) systems that can disrupt the operations of both drones and manned aircraft.

We have seen hints of this already with some nations fielding GPS-jamming systems for use against systems such as JDAM bombs. The USSR fielded a BTR-70 mounted system designed to prematurely detonate proximity-fused artillery rounds.

As far as I am aware, EW systems do not need any special materials like explosives, just commercially available electronic components.

Even if the enemy does allow drone systems to function, there is still a need for human ground reconnaissance and this is likely to remain true for many years to come.

For most of human history, the primary reconnaissance system had been horse or camel-riding cavalry.

Cavalry enjoyed a “mobility differential” over other types of combat troops. The mounted cavalry were significantly faster and more mobile than the marching infantry man, the horse-drawn gun carriage and the supply wagon.

This mobility differential meant that cavalry were often tasked with missions such as:

By the 1930s, it was obvious that the horse as a reconnaissance system was becoming obsolete.

At the same time, many armies were forming tank units and motor vehicles in general were seeing wider use.

Some other system of reconnaissance would be needed.

Understandably, most armies of the time decided that motorizing their cavalry forces was the solution. Other cavalry regiments became tank units.

Despite these changes, cavalry was to lose its monopoly on mobility. The infantry, engineers, artillery, logistics and other branches of the army were also acquiring vehicles. The advantage in mobility that cavalry had enjoyed significantly decreased.

Aircraft offered a considerable mobility differential over cavalry, and were to see increasing use for long range reconnaissance.

The cavalry heritage of ground reconnaissance and tank forces has left a legacy of attitudes.

In many minds, ground reconnaissance and cavalry are essentially interchangeable. Note that NATO map and TOE symbols use the same symbol for either cavalry or reconnaissance.

Nearly a century later, some tankers persist in the opinion that the true role of tanks is to act as an independent raiding force.

The assumption that any enemy would do the same lead to the flawed US Army Tank Destroyer Doctrine.

The German Army in 1939 established that such missions may be conducted more effectively by combined arms forces.

Some theorists still talk of the desirability of a mobility differential for reconnaissance forces. It appears to be lost on many of them that the quantity of this difference is barely significant for modern ground vehicles.

Difference in speed between reconnaissance elements and the main force has dropped to a single order of magnitude and may be as low as under 50%.

The association of vehicle reconnaissance with cavalry has often caused reconnaissance forces to be tasked with other traditional cavalry missions.

These might be termed “Cavalry Operations Other Than Reconnaissance” (COOTR)

That reconnaissance forces needed vehicles was clear. What form of vehicle the newly motorized reconnaissance forces needed was less certain.

From the 1920s onward, everything from motorbikes to main-battle-tanks was tried for reconnaissance.

Armoured cars had first been used as fire support and raiding vehicles. Resembling light tanks, with a higher road speed, they were a common choice for reconnaissance or light cavalry formations.

Armoured cars were either used for scouting, or as fire support vehicles to help extricate scouts from danger.

Many models of armoured car had dual driving positions, and sometimes two drivers, allowing the vehicle to move with equal faculty in either direction and get out of trouble a fraction quicker.

Most armoured cars use roof hatches as their primary means of entry and exit. This was less than ideal if a scouting mission required frequent dismounted movement. Most German armoured cars had open roofs, which only partially alleviated the problem. Black panzer coveralls were not ideal when stealthy on-foot operations were required.

In my article, the “Screen and the Machine”, I challenge just how effective patrolling in fast-moving vehicles is.

Competent enemies will hear a vehicle approaching at some distance and simply take cover until it has passed.

The same challenge can be given to reconnaissance forces. How will you be able to observe an enemy if he can hear you coming?

When discussing reconnaissance vehicles, lip-service is often paid to the idea that the reconnaissance vehicle needs to be compact, stealthy and swift.

In practice, the vehicle may not be particularly small, and not significantly stealthy. Only a small advantage in speed is often apparent, and the ground vehicle is slower than likely threats such as drones and helicopters.

Reconnaissance is, of course, a very broad and varied category of military operations.

The US Army categorizes the forms of reconnaissance as route, zone, area, special, or reconnaissance-by-force. Within these forms may be elements of site reconnaissance, terrain reconnaissance, amphibious/water-obstacle reconnaissance, beach reconnaissance, engineering reconnaissance, artillery/airstrike target acquisition, reconnaissance-by-fire and CBRN/NBC reconnaissance.

Nearly as broad is the range of vehicles that have been offered as “reconnaissance platforms”.

Manufactures would have us believe that any vehicle not a MBT or SPH has a reconnaissance role.

They run the full range from motorbikes and jeeps to well-armoured tanks or assault guns. In the middle are an assortment of unarmoured vehicles, armoured scout cars and armoured cars. I have even seen reports of the M729 Combat Engineering Vehicle being used for reconnaissance by fire missions!

Some of these platforms are more usefully thought of as “reconnaissance support” rather than reconnaissance vehicles.

Some are only reconnaissance vehicles in the sense that they may be used to move scouts.

The configuration of some commonly used vehicles does not facilitate dismounting for reconnaissance.

Many schemes of organization and equipment for reconnaissance units are clearly intended to optimize it for a single type of reconnaissance mission. In practice, such units are often tasked with a variety of missions and found wanting.

Reconnaissance has been flippantly described as “driving around until the enemy takes a shot at you”.

Missions such as reconnaissance-in-force and reconnaissance-by-fire do need a force to have reasonable levels of protection and firepower.

To further complicate this picture, due to their mobility, forces designated as reconnaissance are often tasked with other types of missions such as fire-support, mobile reserve, rapid-reaction, reinforcement, raiding, delaying, escort, security, flank-protection, traffic control, pursuit and counter-reconnaissance.

On a non-linear battlefield, there is often little point in reporting an enemy rather than engaging. By the time another unit can act on the information, the enemy may have disappeared!

The Second World War was a fertile test bed for the then relatively new concept of motorized and mechanized reconnaissance forces.

In the early stages, a variety of lightly armoured and unarmoured vehicles were used, selected for small size, speed, agility and ease of concealment.

As the war progressed, experience showed that reconnaissance elements might have to defend themselves, fight for information or be used for combat roles.

Formations either converted to heavier vehicles or began to use a mix of light vehicles with more combat-capable ones.

Two wartime formations are of particular interest:

The first is the British Armoured Car Regiment (a battalion-sized formation). These regiments were in fact multi-purpose light armour forces with reconnaissance being just one of their roles.

Before the war, such formations had been effectively used to “police the empire”.

Post-war British Armoured Car Regiments were to prove a useful asset in COIN and LIC operations. Many Armoured Car Regiments later converted to using light tanks of the CVRT family (Scorpion, Scimitar/Sabre) but retained their character as a multi-purpose light, mounted combat force.

The other formation of note was the German Reconnaissance Battalion. As the war progressed, this formation was modified until it evolved into a compact, capable combined-arms formation.

Its armoured cars would become supplemented by a company of half-track (Sd.Kfz 250/9) or fully tracked scout vehicles (Sd.Kfz 140/1 or Sd.Kfz 123 “Luchs”).

The battalion also included at least one company of armoured infantry.

Organic support included engineers, assault guns and mortars.

The combat power of this formation could be used to create an opening in the enemy lines that the scout elements could penetrate through. It was also useful for rescuing a compromised scout element or for holding a discovered enemy long enough for line battalions to arrive and engage it.

The Germans commonly made use of captured equipment. Captured armoured cars were very useful for scout platoons that had to operate behind enemy lines.

A feature common to most scout company TOEs was the inclusion of an element that could provide support fire for the scouts.

In German formations this was a platoon of armoured cars or half-tracks mounting the 7.5cm L/24 gun.

British Regiments used an armoured car variant mounting a 75-76mm gun.

American battalions included 75mm M8 HMCs.

The arrangement of having a mix of scout units and a support fire unit can be seen in many post-war formations.

In FM 17-97 the M3 Bradley CFV is supported by the M1 MBT, and the HMMWV scouts by a TOW-armed HMMWV variant. The suitability of TOW as a suppressive fire and general fire-support weapon is open to question, however.

If a unit is expected to fight for information or is to be used in non-reconnaissance combat roles, it needs adequate firepower and protection.

If the intention is to provoke an enemy into prematurely showing their hand, a case can be made for the reconnaissance element’s vehicles not appearing too distinctive from those of the main force.

There is obviously an attraction in letting a light reconnaissance element pass by to attack the possibly more vulnerable main body.

Roles such as reconnaissance-in-force and reconnaissance-by-fire suggest that a well-rounded combined-arms force is the best choice for an armoured reconnaissance formation.

Such combined-arms reconnaissance forces are an obvious choice for hunting guerrillas.

A combined-arms reconnaissance force might have an armoured scout platoon for close reconnaissance, a tank platoon, one or two platoons of armoured infantry/armoured pioneers, an engineer section and a mortar section.

The scout platoon would include several six-man dismount teams, giving it a secondary infantry role. The scout vehicles themselves are likely to mount superior sensor systems to those mounted on the tanks and IFVs. Scout vehicles would also serve as base-stations for reconnaissance drones/UAVs and ground sensors.

Ideally, many of the units in the force described would be organic to the formation to create a cohesive and versatile combat and reconnaissance task force.

The scout platoon might be a battalion asset that is attached to a company task group when needed.

The increased significant of components of Third Wave war-forms may see changes to the reconnaissance and surveillance capabilities of combat battalions and brigades.

The need to gather, transmit and utilize information may see a increase in both size and diversity of reconnaissance and signalling components.

The future combat force may control an area more by observation than by firepower.

John J. McGrath notes in his book “Scouts Out!”:

“In all recent US Army conventional operations, the most common type of action was movement to contact, a type of operation in which the lead unit, whether cavalry or not, was effectively the reconnaissance element. Similarly in nonconventional operations such as counterinsurgency, where there are no actual front lines, all combat (and even most combat support and some combat service support units) units become de facto reconnaissance units by the nature of the conflict...Instead of being a function of specialized troops, perhaps reconnaissance is one of many functions of manoeuvre units similar to attack, defend, or move. Commanders cannot misuse units if they are organized and equipped to perform a variety of functions, of which reconnaissance is but one.”

Modern armour, infantry, artillery, and engineers units now have a level of mobility similar to that of specialized cavalry/reconnaissance formations.

There is an obvious advantage for a brigade or division commander being able to assign a reconnaissance, raid, pursuit or similar mission to the manoeuvre element that is currently best positioned to conduct it rather than wait for a specialist formation to relocate. A combined arms force may be better structured to handle unforeseen obstacles or opposition.

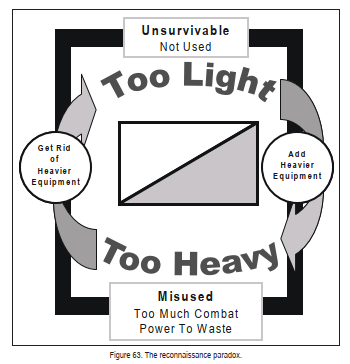

McGrath also talks of the “reconnaissance paradox”:

“Since 1914, the light-heavy debate has dominated thought on the organization and employment of reconnaissance forces. However, the debate creates a paradox (figure 63) that has kept it alive since World War II. If the forces are too light and, while stealthy, not survivable on the battlefield, or so perceived, commanders tend to use other units for reconnaissance operations. Usually, the choice of a replacement reconnaissance unit has been whatever element is the lead unit in the movement. This has been particularly true in operations with a high operational tempo. Most US Army conventional operations since 1970 have been such maneuvers.

“On the other hand, if the reconnaissance force is too heavy or has a mobility or firepower differential equal to that of the bulk of the force of which it is a part, commanders tend to use the reconnaissance element as an additional combat maneuver or support force. This tendency reflects another propensity: commanders almost always feel their commands possess a shortage of combat maneuver units in relation to the missions assigned them. In most recent US Army operations, armored cavalry regiments and divisional cavalry squadrons have been given major combat missions or been attached to subordinate combat organizations to give those units additional combat power.

“Additionally, in light infantry units where the reconnaissance elements are often the only organic mobile element, commanders have found this mobility differential to be more important than the need for reconnaissance. Accordingly, these reconnaissance elements were often used as mobile reserves and counterattack forces.”

This suggests that “manoeuvre reconnaissance” for a brigade is best conducted by its manoeuvre elements. A brigade’s reconnaissance battalion, if present, should be structured towards conducting long-range reconnaissance, including sensors, aviation, LRSU and UAVs.

In “Mechanized Infantry”, Richard Simpkin notes on page 76:

“Reconnaissance is about a pair of eyes and ears, nowadays backed up by an array of electronic and optronic systems, and a radio set...The correct solutions to armoured reconnaissance surely lie at the two extremes -- a British patrol mounted in the Fox scout car, or a main force subunit. Many experienced British cavalry officers regard even the CVR(T) family as too cumbersome and firepower orientated, and many American counterparts might well prefer a jeep to most of the hardware they have been offered in recent times. These officers, and their German and Soviet opposite number too, would be unanimous in maintaining that armoured reconnaissance is a specialized role -- and that the other classic cavalry roles [COOTR] still call for a specialized force.”

On page 114 of the same publication, Simpkin illustrates a composite armoured company with four armoured platoons and a reconnaissance platoon.

The reconnaissance platoon has four AVR(W)s, with a “light APC” (presumably also wheeled for comparable speed and mobility) for the HQ section.

The four composite armoured platoons, each have three gun-tanks, three support-tanks (tracked IFVs) and three dismount elements. Each composite armoured platoon also has a HQ section with a gun-tank, a command version of the support-tank and an AVR(W).

Company HQ has two command variant support tanks and one AVR(W). The company also has a logistic platoon, an armoured recovery vehicle (ARV), and an armoured vehicle-launched bridge (AVLB).

In Simpkin’s later book, “Antitank” he suggests an alternate structure that moves the AVR(W) platoon to battalion level and expands it to five sections of two AVR(W).

By giving the composite company/battalion a platoon of light vehicles, Simpkin has given this combat formation the capability to also conduct both light and heavy armoured reconnaissance.

We are told very little about the AVR(W), other than it has a two‑man crew, so is not the three‑man Fox CVR(W). The inclusion of the AVR(W) in most of the HQ sections suggest a design also suitable for use as a liaison vehicle. This may suggest Simpkin was modelling the vehicle on the Ferret Scout Car. An LPMV‑type vehicle is a possible option.

The reconnaissance platoon might benefit from some dismounts. If each AVR(W) in the reconnaissance platoon is given a crew of four or five, the unit’s manpower would be doubled while still keeping the platoon relatively compact.

Four or five crew allows a two or three‑man dismounted scout team while keeping the driving seat and weapon station manned.

The light APC used as the reconnaissance platoon HQ would possibly be sometime resembling the Saracen FV604 command vehicle, or an AVR(W)‑derived equivalent. A nondescript, wheeled command post vehicle would prove useful to many types of units and organizations.

In the past, “medium reconnaissance” for divisions was conducted by divisional or corps‑level cavalry, since they had a mobility advantage over the forces they reconnoitred for.

This mobility advantage no longer exists, so ground reconnaissance is more effectively conducted by a manoeuvre element, and helicopters or UAVs used for medium reconnaissance.

Smaller formations such as battalion-size battle groups or company task groups may have a specialized ground platoon or squad to conduct low-key “close reconnaissance”.

Not all of the lessons learnt in World War Two were retained.

In the early years of the war, light cars such as jeeps and kübelwagens were used for reconnaissance.

Scout cars such as the Commonwealth Dingo, Humber and Morris were effectively jeep-sized vehicles with light armour. Being of small size and less than five feet high, such vehicles were well suited to stealthy reconnaissance operations.

Experience was to demonstrate that if these vehicles were engaged by the enemy, their life expectancy was often very short.

The solution was to support such vehicles with better armed and armoured vehicles such as armoured cars, half‑tracks and light tanks.

Such support vehicles could buy the light cars sufficient time to escape.

Several decades after the war, the US Army created reconnaissance forces using just HMMWVs.

While often described as the modern day equivalent of a jeep, the HMMWV is a considerably larger vehicle, occupying a ground footprint effectively the same as an M113 (7 ft x 15 ft compared to 8.8 ft x 16 ft).

The shortcomings of the HMMWV-based reconnaissance formation are described in detail in this article.

The HMMWV’s theoretical advantage of speed is neutralized by its extreme vulnerability. The fastest route is not always the safest!

The primary function of a reconnaissance vehicle is to move a set of eyes, and possibly other sensors, and communicate the information found.

For a reconnaissance vehicle, survival is a balance between protection and stealth. If your vehicle is noisy and has no protection, your life expectancy will be low.

Many other reconnaissance missions are better performed with stealth.

Stealthy, dismounted patrolling, and stationary observation are two of the most important strategies for gaining information by ground reconnaissance.

Recognition of this fact does not seem particularly evident in some reconnaissance force structures or proposals for future scout vehicles.

Light tanks and armoured cars are not needed for actual reconnaissance.

The best choice for stealthy ground reconnaissance is a small party of well-trained dismounted troops.

This does, however, pose the question as to how a force of foot scouts reaches the area of interest?

There is little point in sending a stealthy force when the considerable bulk of a nine foot high and twenty-three feet long Stryker vehicle that transported them is nearby!

The use of small vehicles such as jeeps has already been mentioned, as have some of their shortcomings.

If a transport vehicle for foot scouts is obliged to move across country and between cover to avoid contact with the enemy, this suggests a tracked vehicle may effectively be swifter than a wheeled one.

In another article, I suggest a compact tracked reconnaissance and surveillance vehicle I call the Terrier.

The Millenibren may be another possibility.

An updated version of the M113 ACAV is another good option for moving a scout team across country, being more capable than a HMMWV off-road, better protected and amphibious.

The M113 hull is only six feet tall, the same as a HMMWV, making the vehicle much easier to conceal than an M1127 Stryker.

If creating an undated M113-based armoured scout transport, the Italian VCC-1 Camillino IAFV would be a good starting model:

The 30mm ASP cannon sadly never got beyond preproduction. The M230 chain-gun is a possible alternative.

The 40mm automatic grenade launcher is another alternative, particularly if it has air-burst capability. The long minimum range of the AGL (75 metres) may be a problem in some terrain.

The scout vehicle should also have some measure of defence against aircraft and drones/UAVs. A Singapore company offers a mounting that will hold both a 40mm grenade-launcher and a .50 machine gun. Several models of one-man turrets mounting both 40mm grenade-launchers and .50 machine guns are also available.

The reconnaissance support vehicle (RSV) is designed to provide fire support and air defence for highly mobile scout and raiding forces. It is intended for operations where heavier support vehicles would prove too slow or a logistical burden.

As explained earlier, it is most realistic that scout-carriers operate as a component of a combined-arms force. It is still useful if the scout platoon has some organic fire-support for situations when the supporting tanks, infantry, air-defence and mortars cannot respond in time.

The tracked version of the RSV uses the same hull as the scout-carrier, but carries additional ammunition instead of dismounts.

A powered turret or remote weapon station mounts a 25x137mm or 30x113Bmm (LW30) cannon, a co-axial machine gun, and an automatic grenade launcher with air-burst ammunition. The automatic grenade launcher will be less necessary once air‑burst ammunition for the LW30 is issued.

For several decades, helicopters and other aircraft have been capable of engaging ground targets from ranges in excess of five kilometres. It seems unlikely that the RSV's cannon will often be within range of airborne targets.

The LW30 cannon may be a more practical choice than the 25mm. Airburst or proximity-fused 30mm ammunition may be more useful against short-range airborne targets.

Pylons on the turret permit the mounting of FFAR rocket packs and ATGW launch-tubes.

Possibly, vertically-launching missile tubes for ATGWs and SAMs could be installed in the rear section of the vehicle. This latter option suggests that the RSV may be a lightweight variant of the Thunderback concept.

One option that has been used by some military forces is to use nondescript vehicles such as Toyota pickups to move scouts.

The Toyota’s cross country and road performance is similar to vehicles like the HMMWV but without the high price tag.

Effectively, using a Toyota is a sort of mimesis camouflage, since such vehicles are also common in civilian or enemy hands.

The enemy may hear the vehicle coming and may hide from it, but it will not obviously be a military or enemy vehicle.

In this particular context, the vehicle is being used as a transport to move the reconnaissance element and their equipment, and not as a reconnaissance system itself.

How effective this strategy is will depend on a number of factors.

In some war-zones any vehicle that is not positively identified as friendly may be fired upon. An unarmoured Toyota cannot take much damage.

Covert armouring and hidden weapon mounts is a possible option, but this is still not really a vehicle for sustained combat. It may be that a Toyota-mounted unit will need to be supported by a nearby heavier detachment, as was done for jeeps and scout cars in the Second World War.

The German reconnaissance battalions that were equipped with scout halftracks (Sd.Kfz 250/9) retained a company of 8-wheel armoured cars, no doubt for missions they were more suited for.

In much the same vein, it is suggested that a modern combined-arms brigade include a company of Toyotas or Toyota-like vehicles. A small number of Toyotas would doubtless prove useful to any battalion as liaison and runabout vehicles.

One form of reconnaissance vehicle I have not yet mentioned is the motorbike.

Motorbikes are better at moving through certain types of terrain than many other types of vehicle. On the other hand, bikes lack the protection of both armour and stealth.

German reconnaissance forces in the early part of the war used large numbers of motorbike-mounted troops. In the latter part of the war their use was reduced as their vulnerability to competent defences became obvious.

The US military is currently investigating quieter electric motorbikes such as the “Stealth Hawk”. While this is an interesting development, I do not believe it is the best solution for transporting stealth reconnaissance teams.

I believe the best current option for transporting foot scouts is the mountain e-bike.

Details of an experiment using mountain-bikes with LAV-25. Suggested is six bikes per platoon of four LAV-25s.

By the Author of the Scrapboard : | |

|---|---|

| Attack, Avoid, Survive: Essential Principles of Self Defence Available in Handy A5 and US Trade Formats. |

| |

| Crash Combat Fourth Edition Epub edition Fourth Edition. |

| |

| |